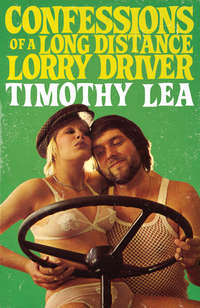

Confessions of a Long Distance Lorry Driver

This may well be the moment to say goodbye. Olga was not amused when I told her that I thought the Red Square was a geezer called Brezhnev and it is clear that there is another side to her nature that I have not been fully exposed to. Life with Olga would not purely be a question of getting tossed off in Rostov.

Whilst my fair companion snuggles closer to her wodka bottle I slip into the threads provided by Boris. They may go down a bomb in the Stalingradski Prospect but I don’t reckon that they are going to pull a lot of birds down the baths hall. Still, that is not my number one problem at the moment. Blowing what I hope is a farewell kiss to the toast of the Neva, I ease open the cabin door and stick my hooter out into the corridor. Not a sausage. Less sign of a human being than there is of a knot in a Scotsman’s used french letter – at least, that is, until I start walking down the corridor. Then Boris’s boots appear down the steps, closely followed by the rest of his body. He eyes me suspiciously and the nozzle of his submachine-gun starts giving percy palpitations.

‘There you are!’ I say in a flash of creative desperation. ‘I’ve been looking for you everywhere. Olga wants you.’

The way I say ‘wants you’ must make it clear to him that she is not seeking someone to unblock a stuffed up plughole.

‘Me?’ Boris’s chest swells visibly. I don’t know about the rest of him, I don’t look.

‘She’s waiting for you in the cabin.’ I just have time to flatten myself against the wall before Boris charges past. Cupid Lea they call me.

I don’t hang about but canter up the steps and stick my bonce above deck level. Still no sign of anyone. I can hear the strain – and it is a strain, make no mistake about it – of an old Russian folk tune coming from the front of the boat. The crew must be having a musical evening. Good luck to them. Over to the rail I go and look over the side. As if to signal my good fortune the moon comes out and there, shimmering beside my reflection, is the outline of a dinghy. I take another quick glance about me and slip over the side. Fortunately, I manage to cling on to a rope before I do myself a serious injury. A few moments dangerous dangling and my feet scrabble against the side of the dinghy and manoeuvre it beneath me – it’s not getting too exciting for you is it? Good. I wouldn’t like to think that I was doing Alistair MacLean out of a living. Anyway, there I am, poised over the dinghy. The strength in my arms gives out and I tumble into the bottom of the boat. For a moment, it rocks alarmingly and then settles down to tap angrily against the side of the larger vessel. Quickly, I undo the piece of rope at the sharp end, and push off with one of the oars.

Free! What an evening for my treasure trove of memories. The dinghy drifts down the side of the boat and I prepare to row to the shore. Most of the portholes show round circles of light but one has a pair of bum knockers jammed up against it. I imagine that Boris must be enjoying his Saturday constitutional.

CHAPTER TWO

In the end it is eight o’clock in the morning by the time I get round to Sid’s place in trendy Vauxhall. The blooming current carried me all the way round to Plumstead Marshes before I was able to get ashore.

I am not in a good mood and it is with no little force that I bang on the heavy brass doorknocker. Frankly, I am surprised that nobody has nicked it. When they moved in, Rosie said that the area was coming up but a glance around suggests that most of it is coming down – either falling or being pulled. Looks like Sid got lumbered again. It is no good being the only house in the street with a lilac front door if it has ‘Poufdah!’ written on it with an aerosol paint spray. The door opens and there is Rosie wearing a black robe with Chinese dragons all over it. She is carrying a glass of orange juice.

‘You’re not having another kid, are you?’ I say, clocking the mittful of vitamin C.

‘Of course I’m not! I’m having my breakfast. What are you doing round here?’

‘I’m looking for Sid,’ I say, pushing past the colour supplement life-style and entering the house. Rosie has changed a lot since she got into the boutiques and wine bars. You would never catch her drinking orange juice for breakfast in the old days. Then it was a cup of tea and a marmite sandwich.

‘You might wipe your feet,’ she says. ‘And why are you wearing that ridiculous suit?’

I don’t answer her because I have just clapped eyes on Sid. He is sitting at a scrubbed pine table and reading a glossy brochure entitled Jetsetter Holidays in Brazil.

A puzzled and unhappy expression settles over his face as he sees me. ‘What are you doing here?’ he says.

‘I just walked from the Copacabana Beach,’ I tell him. ‘You can forget that for a start. “Drift across the Atlantic and taxi down the coast of South America to Rio de Janeiro.” I should cocoa!’

‘Are you coming, too?’ says Rosie. ‘Sid never tells me anything.’

‘I was going on ahead,’ I say. ‘By sea. I don’t suppose Sid told you that?’

‘He said he had to meet someone,’ says Rosie. ‘What is all this?’

‘Where’s the bed?’ says Sid. ‘You haven’t damaged it, have you? I sunk a lot of investment in that.’

‘You sunk it to the bottom of the Thames,’ I say. ‘It didn’t stay afloat more than a couple of hundred yards. It’s a miracle that I’m alive!’

Sid claps his hands to his head. ‘Gordon Bennett! I might have guessed you’d make a mess of everything. What is it about you?’

‘What are you two talking about?’ says Rosie.

‘Sid wanted me to drift round the world on a floating bed,’ I tell her. ‘The trouble was that it didn’t float.’

‘You didn’t have to drift,’ says Sid. ‘You could have rowed a bit. Your attitude’s typical of so many young people today. You want everything on a plate. It’s getting so a kid expects a Duke of Edinburgh Award for pulling out a sheet of bog paper.’

‘Drifting round the world on a bed?’ echoes Rosie. ‘That’s dangerous.’

‘Oh, belt up!’ snaps Sid. ‘If you want to say anything you can blame your perishing brother for putting the mockers on our holiday.’

‘What do you mean?’ says Rosie.

‘I can’t charge it to expenses if he hasn’t gone, can I? Just think about it. We might have had to wait there for months until he showed up.’

A glance at Rosie shows me that she is torn by what I have heard described as conflicting emotions. ‘We’re not going?’ she says. ‘But I’ve got all the clothes.’

Sid shrugs. ‘You’ll have to send them back to Carmen Miranda’s estate, won’t you?’

Rosie turns to me. ‘Are you sure you didn’t act a bit hastily, Timmy?’

‘I acted hastily, all right!’ I say. ‘If I hadn’t, it would be my corpse standing here! You don’t seem to understand the seriousness of what I’m telling you. I was nearly sent to my death.’

‘And I’d set my heart on it, too,’ says Rosie, sinking into a chair – for a moment, I think she is talking about me kicking the bucket.

‘You know who to blame,’ sulks Sid, wiping his cakehole on the tablecloth and picking up his golf putter.

‘It’s not fair, those Rightberks gallivanting round the world while we can’t go anywhere. I thought you’d bought control of the firm?’ Rosie looks at Sid accusingly.

‘Yeah, so did I, but it’s more complicated than that.’ Sid puts a glass on the floor and prepares to tap golf balls into it. I would have chosen one that was not half full of orange juice, myself, but I have noticed before that Sid is inclined to get flustered when Rosie starts having a go at him.

‘Mind what you’re doing, you great pillock!’ It is sad to hear Rosie talking like that. I can remember the time when she used to think that the sun went in every time Sid zipped up his fly.

‘Belt up, slug nipples!’ It is clear that feelings are running high and I am not sorry when there is a sharp rat-tat-tat on the front door.

‘I’ll get it,’ I say.

The sound of battle is still ringing in my lugholes as I swing open the door and find myself staring at the back of the postman’s head.

‘Hello, darling,’ he says, giving my left nipple a playful tweak. ‘Look at those naughty doggies. I wouldn’t mind having a bit of that, would you?’

‘Why don’t you ask one of them?’ I say.

The bloke whips round and turns an interesting shade of scarlet. ‘Oh yes-er. Recorded delivery,’ he says, shoving a pencil stub and a piece of paper into my hand. ‘Sign here.’ He looks me up and down questioningly. ‘Are you an au pair boy?’

The sooner I get out of this tunic the better. It does make me look like a blooming waiter. ‘That’s right,’ I say. ‘You’re the commandant of the Boys’ Brigade, aren’t you?’

‘Watch it!’ The bloke is swift to take umbrage.

‘You want to watch your hands, and all!’ I take the letter and close the door firmly in his face. Honestly, I don’t know what public servants are coming to these days. It makes me glad that I still have his pencil.

‘What is it?’ says Sid, as I go into the room. ‘Another bleeding bill?’

‘I don’t think so,’ I say. ‘It’s got a French stamp on it.’

‘That doesn’t mean anything,’ says Sid. ‘Now we’re in the Common Market I’m probably paying French taxes. Give it here!’ He wrenches it open and I watch his lips begin to move as he tries to get his mouth round the words. I wonder who could be writing to Sid from France? ‘Blimey!’

I don’t know if you have ever seen a bloke’s face turn ashen but that is what happens to Sid’s mug. All the colour drains out of it.

‘What’s the matter, Sid?’

‘They can’t do it!’

He lets the letter flutter to the ground and I pick it up. The notepaper crackles like a new fiver and is headed ‘Villa Splendide, Cap des Riches, Cote d’Azur’. I look down the bottom of the letter and it is signed ‘Plantagenet Rightberk’. It is not an easy letter to understand, but basically the meaning is clear: Sid is out on his ear.

‘Just when I was coming to grips with my slice,’ he whines. ‘It’s tragic.’

‘Don’t take it too hard, Sid,’ I say. ‘They are offering you a golden handshake.’

‘Golden handshake?’ Sid’s features crumple up like a sheet of baking foil. ‘It’s more like a clip round the lughole with a piece of lead piping! Taking inflation into account, it’s less than what I put into the business.’

‘You haven’t made a mess of it again, have you?’ says Rosie speaking my mind for me. ‘Really! You’re like a big soft kid. You want to get yourself an accountant and a solicitor if you’re going into business.’

‘You can’t trust them,’ snaps Sid. ‘They’ll bleed you dry and take you to the cleaners.’

‘At least, that way, they won’t get blood over the machines,’ I say.

Sid is not amused. ‘Shut up!’ he says. ‘There’s nothing funny about this. Seeing a noble lion dragged down by a pack of jackals is a tragic spectacle.’

There is much more in this vein followed by threats of legal action, letters to MPs and a bunch of fives up the hooter, but by half past three Sid is off to bullock (bullock’s horn: pawn) his golf clubs and sign on at the Labour. I feel sorry for him, but not so sorry that I offer to break open my piggy bank with my Xmas club. Years of experience suggests to me that it will not be long before Sid comes up with another imaginative and foolproof way of losing money.

Two evenings later, I am proved correct. We are sitting in the saloon bar of the Highwayman – all the toffs go in the public bar, these days, because they reckon it’s where the locals hang out – and I am allowing the maestro of moan to treat me to a pint and a torrent of ear-bending rabbit about how badly he has been put upon.

‘Sometimes, I feel like chucking it all in,’ he says. I can’t help wondering what ‘it’ he is talking about but I don’t say anything. ‘It’s no good belonging to a large organisation in this country. If you’re a boss then you can’t get anyone to work for you and if you’re a worker then the bosses are trying to exploit you all the time. People don’t have any confidence in each other any more.’

‘That’s my pint you’re drinking,’ I say.

Sid puts the glass down and wipes his mouth with the back of his hand. ‘Are you sure?’ he says, suspiciously.

‘Positive,’ I say. ‘You know that bloke who went to the karsi?’

‘I don’t know him,’ says Sid.

‘I thought you must do,’ I said. ‘You’d drunk half his pint before he even stood up.’

Sid picks up his empty glass, looks round nervously and starts edging down the bench. ‘Big bloke, wasn’t he?’ he says. I nod. ‘Just shows how overwrought I am. I don’t know what I’m doing.’

‘I’d better get you another pint to help calm your nerves, hadn’t I?’ I say.

Sid nods. ‘Ta. I think a Mahatma Ghandi might slip down all right now you make me think of it.’

‘Instead of?’ I ask.

‘No, as well as. I can’t drink brandy by itself.’

‘You poor bastard,’ I say. ‘You really suffer, don’t you?’

Sid is never swift to detect when one is being sarcastical and he merely nods and starts prospecting for crunched up crisps in the bottom of a discarded packet. I get the drinks in and notice that the big fella has come back from the karsi – you would hope him to, wouldn’t you? – and is looking at Sid and his empty glass with equal interest.

‘Ta,’ says Sid when I get back to the table. ‘You know, I’ve been thinking.’

‘I’m not certain it suits you,’ I say.

‘About what I was talking about earlier,’ says Sid. ‘I reckon the only thing to do is to be your own governor. That way, nobody can let you down or mess you about. You’re responsible for everything that happens.’ A faraway look comes into his eye. ‘You remember what it was like when we were cleaning windows?’

‘You mean, all those birds?’

Sid frowns. ‘I wasn’t referring to that. I was talking about how easy it was.’

‘It was pretty easy with the birds,’ I remind him.

‘No forms, no taxes, no clocking on, knock off when you like.’

‘And who you like,’ I chip in.

‘Money isn’t everything. I’ve said that before.’

‘You say it every time you’re skint,’ I remind him. ‘There’s two lots of people who never worry about mazuma: those who’ve got so much of it they don’t know what to do with it and those who haven’t got any.’

‘Very philatelical,’ says Sid. ‘But, frankly, I’m not interested in what you pick up from those religious programmes before the Sunday film. It’s job satisfaction I’m after.’

‘Hear, hear!’ The words do not issue from my shapely cakehole but from the big geezer whose beer Sid nicked. He is leaning towards us with an expression on his face that can only be described as rapt. ‘I couldn’t help overhearing what you were saying because I was listening very carefully,’ he says apologetically. ‘It’s seldom that I find myself in such complete and utter agreement with anyone.’

‘Ta, that’s very nice of you,’ says Sid. ‘Would you care for a drop of something? I’m certain my friend here would be happy to—’

To my relief, the bloke holds up a hand. ‘Thank you, but no. I hardly touch the stuff.’ That is certainly true when you have Sid sitting next to you. The bloke smiles and shakes his head admiringly. ‘Working for yourself, it’s the only way. I ought to know.’

‘You’ve got your own business, have you?’ asks Sid.

The bloke’s face clouds over. ‘Not for much longer, I’m afraid.’

‘It’s not easy these days, is it?’ says Sid, putting on his head mourner face.

‘It’s not that,’ says the bloke. ‘The business is going like a bomb. It’s the wife.’

‘Oh, I’m sorry,’ says Sid. ‘She’s-er, um-er, has she?’

‘Nothing like that,’ says the bloke. ‘She wants us all to go to Australia. Our eldest girl married an Australian. She kept writing all these letters and it got Mavis going. Now we’re off. I’ve got to sell up.’

‘Your wife’s adamant, is she?’ says Sid.

‘No, C of E, but it doesn’t matter out there as long as you’re not black. She hasn’t half made up her mind, though. Every morning she’s in the back garden with her boomerang. She can throw it right round the house and make it come back again. You wouldn’t credit it unless you’d clocked it coming in through the front gate. The vicar copped it right behind the earhole.’

‘Fascinating,’ says Sid. ‘Tell me, what is the business?’

‘Road haulage,’ says the bloke. ‘We’ve got a couple of lorries and we freelance round the country. Marvellous way of seeing a bit of scenery and getting paid for it. It’s like a caravan holiday sometimes.’

I should be warned when I see mist rising from Sid’s mince pies.

‘It’s just you, is it?’ he says.

‘Me and my boy. We’re our own bosses; work when we like. I don’t mind telling you, I’m going to miss it. Nice little business it was. Some lucky bloke’s going to get a bargain.’

‘About time we moved on, isn’t it Sid?’ I say.

‘Belt up!’ Sid doesn’t even look at me. ‘You haven’t sold up yet?’

‘No, they only confirmed the travel arrangements yesterday. I haven’t had much time to think about it. I suppose I’ll have to put an advertisement in the paper.’

‘Probably the best idea,’ I say, starting to stand up. ‘I hope you—’

‘Sit down!’ Sid yanks me down beside him and leans forward eagerly. ‘Well, Mr—’

‘Rogers,’ says the bloke. ‘William Rogers.’

‘Well, Mr Rogers.’ Sid takes a deep breath. ‘I’m very interested in what you’ve just said. I think we might be able to come to some arrangement.’

‘You know somebody who might be interested?’ says Mr Rogers.

‘I’m very interested,’ says Sid with the finality of a corpse pulling the coffin lid down on itself. ‘Are you sure you won’t have a drink?’

‘Oh well, maybe just this once. I’ll have a scotch, ta.’

‘A large one?’ says Sid.

‘Well – ta.’

Needless to say, it is Timothy Sucker who is despatched to buy the ‘I’m so frisky’ while Sid and Rogers practically hold hands under the table. There is something about the Rogers bloke that I don’t trust. For a start off, anyone who has listened closely to Sid for a few minutes and is still prepared to do business with him must be round the twist. There is also the way he handles the scotch. He throws it down his throat like he is trying to knock a spot off the bottom of his Cousin Kelly. It does not square up with the image of a bloke who hardly touches the stuff.

‘Ta,’ he says, slapping his glass down on the table. ‘Well, that’s all settled then. My girls will show you the merchandise.’

‘Settled?’ I say.

‘Yes,’ says Sid. ‘You know me. I don’t mess about. I’ve agreed a very reasonable price with Mr Rogers and his daughters are going to take us round the garage.’

‘I wish I could do it myself,’ says Mr R. ‘But the wife’s mother is coming round and I want to be at the bedside in case she says anything. You know what they’re like. They read unpleasantness into anything. I didn’t know she was in the garage when I was trying to back the car in.’

‘I thought your daughter was in Australia?’ I say.

‘The eldest one,’ says Mr Rogers. ‘You don’t miss a trick, do you, sonny?’ He gives me a look that is so old-fashioned that it is practically wearing woad.

‘Don’t take any notice of him,’ says Sid, kicking me in the ankle. ‘He’s seen too many Perry Mason programmes. Now, let us know where we can link up with your girls and we’ll start the ball rolling. I must say, I’m very excited about this.’

Another large scotch later, Mr Rogers has made a telephone call to alert his daughters and is informing us of the address to go to. ‘It would be a big help if you could pay in cash,’ he says. ‘I don’t want to get clobbered for a lot of tax just before I leave the country.’

‘You’ll have to give us a bit of a reduction,’ says Sid.

Mr Rogers whistles through his teeth. ‘You strike a vicious bargain, don’t you? I can see you’re no mug.’

Sid looks pleased with himself but I have my doubts as to whether Mr Rogers’s assessment is either genuine or correct.

Half an hour later, my doubts are even greater. Sid and I are rattling the fencing that surrounds a bomb site in British North Battersea. It also surrounds what looks like a scrap metal dump but is apparently the home of ‘Squaredeal Used Cars’.

‘This can’t be the place,’ I say. ‘Let’s go home, Sid.’

‘Belt up,’ says Sid. ‘The bloke said they shared the premises, didn’t he? I wonder if that’s them, over there?’

‘You mean, those two clapped out old wrecks?’ I say, staring at a couple of ancient lorries rusting away in one of the railway arches.

‘That’s not a nice way to talk about two charming young ladies.’

I spin round and see that Sid was referring to a couple of birds who are hurrying towards us. They look as if they are no strangers to the make-up counter of Boots and are clearly not of a shy and retiring disposition.

‘Hello, boys,’ says the one in the scarlet plastic mac. ‘I’m Babs and this is Suzanne. Sorry we’re late. Did Fred – I mean, Dad, give you the key?’

‘No,’ says Sid. ‘I’m Sid and this is my assistant, Timmy. Why are you looking at me like that?’

The bird called Suzanne is indeed staring into Sid’s mug like it is a ‘What the Butler Saw’ machine. ‘It must be the light,’ she says. ‘It’s uncanny.’

‘You saw The Exorcist too, did you?’ I say. ‘A lot of people have commented.’

‘Paul Newman,’ she breathes. ‘What do you think, Babs?’

‘I think he’s more like Steve McQueen, myself,’ says the other bird. ‘Either way, it’s very distracting. How can you be expected to do business with a bloke whose irresistible magnetism reduces you to a shapeless jelly?’

‘Not shapeless,’ says Sid gallantly.

‘He makes Dave Allen sound like Alf Ramsey,’ simpers Suzanne.

‘How are we going to get in?’ I say, deciding that my stomach can’t take much more.

‘We’ll have to climb over the top,’ says Babs. ‘Give us a leg up, Suzanne.’

Without another word, the bird proceeds to insert one of her feet in the mesh and reveal as much of herself as she can while straddling the swaying fence. She is wearing stockings with a black rose on the suspender straps and frilly red panties, I can tell you that without sending for my magnifying glass.

‘Careful,’ says Sid. ‘You don’t want to do yourself an injury.’

‘It’s you who wants to be careful,’ says Suzanne. ‘You’ve got more to lose than we have.’ With these saucy words the bird in the short fur coat with the bald patches proceeds to follow her sister over the fence.

‘Hold on, I’ll give you a hand.’

‘Oooh!!’

‘Sorry,’ says Sid. ‘I didn’t mean to do that.’

‘That’s all right,’ says Suzanne. ‘Your hand was a bit cold, that’s all.’

‘Sid!’ I whisper. ‘You’re not taking these girls seriously, are you? They look as if they’re on the game.’

‘You mind your language!’ Sid is bristling like a turkey’s cock. ‘Just because they reckon me, there’s no need to let your naked envy show through.’

It is no good trying to reason with Sid when he is in one of his moods and I say nothing but follow him over the fence. It’s a good job there aren’t any bules about because they might entertain suspicions.

‘Here we are,’ says Babs. ‘This was the best model they ever made, you know. After 1955 they started introducing plastic components.’ She leans against one of the mudguards which falls to the ground in a shower of dust.’

‘Every part replaceable. It’s so much easier if you do have a little accident. With some of these modern ones you have to buy half a lorry if something goes wrong.’

‘Just in case we do have a prang,’ I say, ‘Where’s the nearest blacksmith’s?’

Babs looks at me coldly. ‘Daddykins said you were sarcastic.’

‘Don’t mind him,’ says Sid. ‘I make the decisions round here.’

‘I should think you could make anything round here,’ says Suzanne running her fingers up the sleeve of Sid’s Gannex.

‘Do you want to get the feeling of the controls?’ says Babs. ‘It’s lovely and snug inside. Do you remember when Daddy used to give us a ride, Suzanne?’