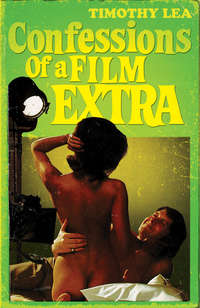

Confessions of a Film Extra

Confessions of a Film Extra

By Timothy Lea

Contents

Title Page

Publisher’s Notes

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Also available in the CONFESSIONS series

About the Author

Also by Timothy Lea & Rosie Dixon

Copyright

About the Publisher

Publisher’s Note

The Confessions series of novels were written in the 1970s and some of the content may not be as politically correct as we might expect of material written today. We have, however, published these ebook editions without any changes to preserve the integrity of the original books. These are word for word how they first appeared.

Chapter One

I do not fancy burning down the warehouse with Sidney, so when the train pulls in at Euston, I slide off home to spend a few days with Mum and Dad. Sidney takes it badly of course, but I am quite Adam Faith about it and will not be Budgied. I mean, I have been through it all too many times before. Whenever there is knavery to be done and Sid says ‘we’ he really means me. And with my luck the matches would be damp and I would try striking one on a copper’s leg while Sid was keeping watch from the nearest boozer with his back to the window.

For those unfortunate enough to have found their local bookshops sold out of Confessions of a Travelling Salesman, I had better point out that my evil brother-in-law Sidney Noggett, needed to burn down a warehouse full of unusable empire-made, multi-purpose cleaners because it was his only means of recovering the money he had laid out in a disastrous deal with a very unworthy Japanese gentleman by the name of Mr Ishowi.

Scraggs Lane, Clapham is the ancestral home of the Leas, although my Mum always points out to people that we live at the Wandsworth Common end of it. She thinks it sounds more refined. A much nicer class of person gets mugged on Wandsworth Common.

When I get to the end of the road it is looking even scruffier than usual, because they are pulling down one side of the street and a lot of people have taken the opportunity of dumping their rubbish along the pavement. It looks like a holiday camp for bluebottles. I am surprised that the slipstream from the ball and chain has not knocked down our house. Sidney always said that it was only kept upright by the woodworm joining together and holding hands.

Still, like the poet says, be it ever so tumbledown, there is no place like home, and I cannot help feeling sad as I watch the lousy old place falling apart. All these highrise flats springing up like fast-growing mushrooms from a cowpat. Only the boozers left like fish heads to remind you of the rest of the body that has been gobbled up. Go in some of those pubs and they have to have the lights on all the time because there are so many blooming great buildings leaning on them, shutting out the light.

It is about five o’clock when I get home and I am not altogether surprised when Dad opens the front door to me. He puts in time at the Lost Property Office and brings a lot of his work home with him. So much so that he is sometimes asked to take it back again. He is also convinced that atomic tests and fluoride in the water supply are sapping his natural juices and for that reason he is dead cautious about going to work unless he feels one hundred per cent. One hundred per cent what, I have never been able to discover. Suffice to say that there are usually one or two days a week when he is ‘resting up for the big push’ as he puts it. Why the Lost Property Office have not got the big push in first I will never know.

Dad’s face when he sees me undergoes remarkably little change except that his mouth drops by one sixteenth of an inch.

‘Oh,’ he says, ‘it’s you. What disaster brings you home?’

‘Your charm school closed down for the holidays, has it, Dad?’

‘Don’t give me none of your lip. I know you don’t come round here unless you want something.’ Marvellous, isn’t it? I have only just appeared on the doorstep and he is within an ace of going into his ‘you use this place like a hotel’ routine.

‘I wanted to see you and Mum,’ I say patiently. ‘This is my home, Dad.’

‘Only when things are getting too hot for you somewhere else.’

Trouble with the old bleeder is that he is usually right.

‘Oh, Dad,’ I say reproachfully, ‘Dad.’ I let my voice tail away like I am too choked and hurt for words, and give a little misunderstood shake of the head. Believe me, Oscars have been won for far worse performances.

‘Well, come in if you’re coming,’ says Dad, singularly unmoved. ‘Don’t hang about there like a great Jessy.’

I cross the threshold and am greeted by the odour of boiled cabbage and rising damp that always spells out home – or, more appropriately, smells out home. The hall looks the same except for a large barometer hanging between the moose head and the tin hat and gas mask. Dad was an air-raid warden during the last war and does not like people to forget the fact. He and Mum live in the past, poor old sods. It was only recently that they took the strips of sticky paper off the kitchen windows.

I tap the barometer and the glass and both hands fall off.

‘Oh, bleeding marvellous,’ hollers Dad. ‘You haven’t been in the house two minutes and you’ve smashed a priceless work of art.’

‘Come off it, Dad. I only tapped it!’

‘Well, don’t tap it! It’s not there to be tapped.’

‘Everybody taps barometers, Dad. It’s like touching things when they’ve got a “wet paint” sign on them.’

‘That’s not the point. That had been there for two weeks without anything happening to it.’

‘I can believe that. The needle was jammed at set-fair. That’s why I tapped it.’

‘You leave things alone that don’t belong to you. You just leave things –’

Where this typically turgid argument would have led us, I will never know because Mum suddenly pops out of the front room all of a twitter.

‘He’s on,’ she says. ‘Come on! He’s on.’ She sees me and waves her hand. ‘Oh, hello Timmy dear. You’re just in time. Come on.’ And she doubles back into the room. I am a spot choked because I always reckon on Mum coming across with some of the human warmth that Dad so obviously lacks. His milk of human kindness has to be reconstituted with draught bitter.

‘What’s up, Dad?’ I ask. ‘Has Mum got a crush on the bloke introducing Blue Peter?’

‘No, it’s Jason. I thought you knew.’

‘Jason? Jason who?’

‘Jason Noggett! Didn’t you know that your nephew was appearing with Miss Mealie?’

‘I didn’t even know Miss Mealie was appearing. What’s it all about, Dad?’

Dad waves his hands in exasperation. ‘Come and watch. Your mother will tell you.’

But Mother is clearly not going to tell anybody anything, except to belt up. She is perched on the edge of her seat and bombarding her cakehole with Maltesers.

‘Mum –’

‘Sssh!’

‘What –?’

‘Sssh! Do be quiet!!’

Cut to the quick by this lack of parental interest, I adjust my peepers to the tellyvision set and listen to the disgusting tinkle, tinkle of ‘Baa Baa Blacksheep’ being picked out on a xylophone. As the sound fades, so a pretty female face fills the screen and a set of perfect gnashers split into a welcoming smile.

‘Hello boys and girls,’ says a voice of such cloying sweetness that I expect to see syrup leaking out of the volume control, ‘are you ready for the music?’ She pauses and nods, and to my disgust I find myself nodding back. ‘That’s good, because when it stops I’ll be back here to introduce my little friends on Kiddichat. The programme where our panel of mini-viewers answer questions from you children at home. So, from me, Miss Mealie, it’s: enjoy the music and see you in a minute.’ She gives a sickening wave and fades out to make way for a bird in a ballet costume who does a little dance to the Dambusters’ March, or some such popular melody. I wait hopefully for her to catch her toe in a crack between the floorboards, but it is not one of my lucky afternoons.

‘Jason is on this lot?’ I ask.

‘Sssh,’ says Mum.

‘Have you got a pin Mum, my leg just fell off?’

‘Ssh!!’

When Miss Mealie reappears, Mum nearly topples off her chair, she is leaning forward so far. ‘There he is,’ she squeals. ‘There he is!’

I look over Miss Mealie’s shoulder and it is indeed possible to recognise Sidney’s first-born with his fingers stuck up his bracket in characteristic fashion. He is sitting at a table with three other kids.

‘Our little Jason, a telly star,’ breathes Mum as if something with a halo round its bonce has started tapping on the window.

‘What is it, Mum, a nose-picking contest?’

‘That’s enough from you,’ snaps Mum and I have not heard her voice so sharp since she caught Dad snogging with Ada Figgins in the Gents at The Highwayman on New Year’s Eve. There can’t be many blokes who have seen the new year in with a lavatory brush shoved down the front of their trousers.

‘Why do they make them wear those stupid shirts?’ I say conversationally. I would have done better to keep my trap shut.

‘I sat up till three o’clock in the morning crocheting that,’ sniffs Mum. ‘Rosie said that the producer thought it was “absolutely super”.’

‘I’m sorry Mum, I –

‘How many times have you been on telly, then, clevershanks?’ says Mum accusingly.

‘He nearly made Police Five a couple of times, though,’ sneers Dad.

It is disgusting isn’t it? Rounding on their own flesh and blood because my mug has never had six hundred and twenty-five lines running through it. The way some people go on about the telly you would think it was some kind of new religion. Certainly not the old one because the only time you see Dad move fast is to turn off the Epilogue. It is as if being exposed to a back to front collar for longer than five seconds was going to kill him.

I should tell them both to get stuffed but I am too fascinated by the prospect of seeing what the infant Jason gets up to.

‘Did you like the dance, Benedict?’ says Miss Mealie engagingly.

Benedict must have been doing something else at the time because he gazes vacantly into the camera as if concentrating on a spot in the middle of it.

‘How about you, Imogen? Imogen!’ The name has to be repeated because Imogen seems totally engrossed in twisting the arm of the small boy next to her. He bursts into tears.

‘Chinese burn,’ says Imogen proudly.

‘Come on, Eric,’ pipes Miss Mealie. ‘You wouldn’t want the fairy to see you cry, would you? Fairies only like brave boys.’

‘They’re keeping the camera off him,’ hisses Ma, incensed. ‘I don’t know what they’ve got against the child. It’s always the same.’

‘Probably waiting ’til he gets his finger out of his conk,’ I say. Mum is so worked up she does not pay any attention to me.

‘He’s the life and soul of the whole programme,’ she chokes. ‘Everybody only watches to see him. There! Look at that.’

Jason has now succeeded in getting both his fingers stuck up his snoz and the camera quickly whips back to Miss Mealie.

‘Is that all he does?’ I say innocently.

‘Don’t be ridiculous,’ snarls Mum. ‘It’s not surprising, is it? Nobody talking to the child. Ooh! I wish I could get my hands on that woman. She’s not as innocent as she looks, you know. Rosie’s heard a few things about her. Oh, yes. I don’t know why she has the little chap on the programme if she’s only going to humiliate him.’

I tune out Mum’s drone and stare at Miss Mealie with fresh interest. She looks the kind of bird who is so simperingly awful that you want to shout ‘knickers!’ into her lughole, but maybe I am doing her an injustice. Perhaps she is a bit of a raver on the quiet.

Eric stops crying when Miss M., quickly shoves a sweet in his miserable little cakehole and at last the camera settles on Noggett junior. The child star has now got his digits out of his hooter and Mum coos with ecstasy.

‘Oh, isn’t he lovely?’

I turn away and look at Dad who winces and shakes his head. I have a feeling that he finds the whole spectacle as nauseating as I do.

‘So, now I can see that Jason is ready to answer our first question. You liked the dancing didn’t you, Jason?’

Jason nods enthusiastically, and you can tell that he is a real chip off the old block. Another crawler.

‘Yeth, Mith Mealie,’ he lisps.

‘Very well, Jason. Here is a question from Sandra Page, aged eight, of Mellow Meads, Wessex Way, South Dene. That does sound a nice place, doesn’t it, Jason? Would you like to live there?’

Jason casts his eyes down and speaks in a thin, reedy treble. ‘I want to stay at home with my Mummy.’

What a pro! I bet that has them crying into their crackers down at the day nursery. Mum nearly bursts a gusset.

‘What a nice thought,’ says Miss Mealie, switching on full beam. ‘Now, let’s have that question. Sandra wants to know what time all the boys and girls on the panel go to bed. When do you go to bed, Jason?’

‘When The Sand Man comes.’

‘And when does he come?’

‘When Dadda goes away. Then Mummy says “You go to bed now, Jason, because Mummy and The Sand Man want–’

‘Yes, well that does sound nice, doesn’t it?’ says Miss Mealie hurriedly.

‘– to be alone together,’ says Jason doggedly. ‘And then sometimes uncle –’

‘Imogen!’ shrieks Miss Mealie, ‘what time do you go to bed?’

‘Depends what’s on the telly,’ says the pretty little mite, starting to chew a pencil she has been jabbing Eric with. ‘If there is a film, I stay up until “bye, bye, light” time.’

‘ “Bye, bye light” time?’

‘When the light runs away through the little hole in the middle of the telly, we say: “bye, bye, light”.’

‘How sweet,’ beams Miss M. ‘You are grown up, aren’t you? “Sand Men” and “bye, bye, lights”–’

‘And uncles,’ pipes up little Jason.

‘He’s a caution, isn’t he,’ says Mum. ‘I don’t know where he gets these things from, I really don’t.’

I was thinking the same about Rosie but I don’t let on. Ever since she went to the Isla de Amori and started reading those women’s lib articles, she has been a different woman. The time was when she thought the sun shone through the slit in Sidney’s Y-fronts. Now he is lucky if she can find the strength to chuck his smalls into the washing machine. I had not realised that her living in the Cromby Motel could create many of the problems that have been afflicting Sidney and myself. I must have a discreet word with her about it. Sidney does have a position to keep up and it is not only the one you find on page fifty-two of Everything you ever wanted to know about sex, but felt such a fool for asking.

I get my chance to speak to Rosie sooner than I had expected, because she rolls up with the infant Noggett an hour later. By taxi, no less, and accompanied by a thin, long-haired git wearing a beard and a shiny leather jacket with coloured panels. He looks a right berk.

‘Oh, mother,’ trills Rosie, all posh-like. ‘This is Dominic Ralph – he produces the show.’

‘Charmed, I’m sure,’ says Mum, and she actually curtseys to the creep. Either that or her knicks have worked up.

‘Sooper,’ says Dominic, taking one of Mum’s hands with both of his – he probably needs two to lift it – ‘absolutely soopah. You’ve got a very talented little grandson here. Is this the proud father?’

He beams at me and I am quick to look disgusted. Likewise Mum and Rosie.

‘Oh, no,’ says Rosie with a light laugh. ‘This is my brother.’

‘Timmy,’ I say. ‘Pleased to meet you.’

‘How do you do.’ Dominic nods and his hair flops over his forehead.

‘Dominic’s going to take me out for a bite to discuss the new series,’ says Rosie, avoiding my eyes. ‘I wonder if you’d mind putting Jason to bed, Mum. I won’t be back late.’

‘There’s some football on telly tonight, Jason,’ I say eagerly. ‘Would you like to watch it with Uncle Timmy?’ I mean, if you can’t lick them, join them. That’s my motto.

‘No,’ says the ungrateful little bleeder, without looking at me. ‘Have you got any thweeties, grandma?’

‘Yes, dear. When you’ve had your supper.’

‘Don’t want any supper! I want thweeties!’ Jason’s fat little lip – it would be a darn sight fatter if I had my way – starts quivering and he turns on his mother. ‘You promised!’

‘Yes, all right dear.’ Rosie looks at Mum. ‘He is a bit over-tired tonight, Mum. Maybe if you did give him a few sweets and put him to bed.’

‘Remember to clean those little toothie-pegs first,’ I beam. ‘We don’t want nasty old Giant Decay rotting them away and causing little Jason excruciating agony, do we?’

‘Are you trying to terrify the child?’ says Rosie angrily. ‘A few sweets aren’t going to hurt him.’

‘Uncle Timmy was only thinking of little Jason’s welfare,’ I say.

Dominic looks at me thoughtfully. ‘Uncle Timmy,’ he says.

‘What?’ Rosie’s expression is like that of a cat seeing another moggy approaching its food bowl.

‘He’s got a kind face. It might be rather nice. Round off the show.’

‘What do you mean?’ Mum looks from face to face inquiringly.

‘Have you ever had any acting experience?’ asks Dominic.

‘No. Well, I mean, I’ve done a lot of work like acting. I’ve been a Holiday Host in a holiday camp and a salesman.’

‘Soopah, soopah.’ Dominic extends a hand and pats me on the wrist. It occurs to me that Sidney may have nothing to worry about tonight. I reckon the last bird Dominic fancied was probably his Mum.

‘You’ve never done any acting in your life!’ quibbles Rosie.

‘I’ve done as much as Conk Digits here,’ I say. ‘Just because I haven’t been to Rada doesn’t mean I haven’t got talent.’

‘Pop along and see me,’ says Dominic, transferring the pressure to my upper arms. ‘No promises, but it might be interesting.’

‘Are you going to put him on the telly?’ says Mum, catching up with the action at last. ‘Oh Timmy, I always knew you had it in you.’

A couple of days later I am sitting at the back of the Studio Five Control Room, waiting for Miss Mealie and the rest of them to come out of Make-up.

“You’ll get the feel of the show up here, ducky,’ breezes Dominic Ralph. ‘Just let it flow all over you and I’ll introduce you to a few people afterwards. That chair comfy enough for you? Goodo! Ah, Melly my darling. How is our lovely girlikin today?’

‘Pissed off!’ snarls Miss Mealie, grinding out a lipstick covered snout in the centre of a half eaten sandwich. ‘If you think I’m going to hang about while those vicious little vermin have their tacky curls lacquered, you’ve got another think coming. Who’s the star of this show?’

‘You are of course, darling. There’s never one shadow of doubt about it.’

‘And while we’re about it, we could do with some new kids. I don’t anticipate that we’d get anything better but at least we’d have a change of mother. Those greedy, grasping, status-seeking harridans are beginning to drive me insane.’ Miss M. produces a small container and swallows a couple of pills. She shudders. ‘Christ! But these things taste disgusting. Just getting them past my gums makes me want to throw up.’

‘Melly,’ says Dominic hurriedly. ‘I’d like you to meet Timothy Lea. His nephew is on the programme.’

‘Oh dear,’ says Miss M., gushingly, ‘me and my big mouth. Please don’t take offence. I don’t mean a word I say. I’m just a bit overwrought at the moment. Let me guess which one is yours. Imogen perhaps? No! Of course not, not with that colouring. Jason? Yes, it must be Jason. He’s so good-looking.’

I know she is bullshitting but I cannot help blushing. That upper-class voice does not help either. I am a pushover for a posh bint.

‘Yes, it’s Jason,’ I say. ‘Rosie Noggett is my sister.’

‘Yes. Very pretty blonde girl. She wasn’t one of the ones I was referring to, of course.’

‘Funny. It sounded just like her,’ I say.

‘Oh, you naughty boy,’ Miss M. waggles a finger at me. ‘You mustn’t try to make me feel any worse than I do. Ah, here they come.’

Rosie and the rest of the Mums and brats crowd into the control room and Miss M. starts behaving like Miss Mealie. She is a very good-looking brunette with a few more lines than you see on the telly. I read her as being about twenty-eight, five foot six and a half and 36c cup.

‘Miss Mealie and panel into the studio please,’ says Dominic. ‘Please don’t play with those switches, boys. And, Imogen dear, that’s not a very good place to put your chewing gum, is it? Give it to Mummy, there’s a good girl. And Mummies, could we have absolute quiet during this show, please? We’re always interested in your comments but we’d like them when we’re off the air.’

‘Look into the camera and don’t stutter, Benedict,’ hisses one mother. ‘Remember there’s that series coming up.’

‘Don’t kiss me, Rupert,’ says another, ‘you’ll smudge your make-up.’

When you see the expression of grim determination on these women’s mugs you can understand what Miss Mealie is getting at. They look like Olympic swimming coaches.

‘Good luck, Jason,’ I say. ‘Don’t forget your sweets.’

‘Shut up, you!’ snaps the little monster, snatching them from my hand. ‘You shouldn’t be here.’

Little do you know, I think. A couple of weeks and you could be one of the youngest has-beens in the business. I can see myself telling him the bad news: ‘Sorry about this, Jason, but you’ll have to make way for a younger child. The public wants youth, you know.’

‘But Uncle Timmy!’

‘No buts, Jason. You’re finished. Pack your dolly mixtures and get out!’

I watch the little basket gobble down another handful of sweets as he takes his place on the set, and try to shut out the canvas chair with his name on the back of it. A couple of hours in this place and you can feel all washed up at the age of twenty-two.

‘On set everybody, please,’ repeats Dominic. ‘We’re on the air in two minutes.’

‘Can I have his autograph when he learns to write?’ I say as I sit down next to Rosie.

‘Shut up, jealous!’ she barks.

Dominic starts speaking soothing words into a microphone that connects with the set and a shapely bint by his side starts giving a countdown. In front of us are a row of tellyvision screens and a bloke on Dominic’s right commands a bank of switches which control the pictures on each screen. I can see Jason’s self-satisfied little mug staring at me in horrible close-up. At least he seems to be able to leave his hooter alone this week.

‘You blocked up his nostrils, did you?’ I say to Rosie.

‘Shut up!’

‘Have you got my pills, darling?’ Miss Mealie’s voice comes through to the control box. ‘I left them on the desk.’

‘Don’t seem to be here, darling.’ A slight edge creeps into Dominic’s voice. ‘Twenty-five seconds to go. Let’s have a good show now everybody. Good luck.’

‘Fifteen, fourteen, thirteen–’ The Production Assistant’s voice drones on, sounding professionally bored.

I look back to the monitor with Jason’s mug on it and watch the little swine slotting another peppermint into his cakehole. Hey, wait a minute! Those are not sweets! With a sense of impending horror I recognise Miss Mealie’s pills. The ones she said tasted so horrible. They could probably kill Jason. And in front of millions of viewers too!