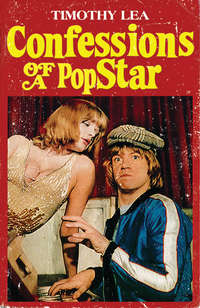

Confessions of a Pop Star

‘Right here in this house. You must have noticed that young Jason is not with us?’

‘He hasn’t run away from home?’ I try hard to keep a note of delirious gaiety out of my voice but it is not easy.

‘Do you know how old he is?’

I pretend to give the question a lot of thought. ‘Let me see. You and Rosie have been married for nearly six years, so he must be about six and a half.’

Sidney’s face darkens beneath the stubble. ‘Watch it, Timmo. Just because he was a bit premature, there’s no need to go jumping to conclusions.’

‘Premature? He was so early he was practically singing at the bleeding wedding.’

‘I won’t tell you again, Timothy. The child is a mature six and very advanced for his age, considering everything. I believe he can open up a whole new child market for us. I’ve sent him upstairs to get his clobber on.’

‘Surely he’s too young, Sid?’

‘Not these days he isn’t. The kids are the ones buying most of the records and the real mini-groovers don’t have anyone to identify with. If we can launch Jason we make our own market.’

When Sid talks like that I find it difficult to understand why everything we touch loses money. It seems such a good idea, doesn’t it?

‘Here I am, Dad.’

Blimey! The little basket looks like an explosion in a sequin factory. Faced with that kind of competition, Gary Glitter might as well get a job as a bank clerk.

‘Can he play that thing?’ I am referring to the kidney-shaped guitar with more sharp corners than a lorry-load of hair pins.

‘He can strum it a bit. The backing group will supply all the noise.’

‘Jason and the Golden Fleas,’ I say wittily.

‘Uncle Timmy, stupid,’ says the only kid in south London to be given a new set of nappies for his fourth birthday.

‘Sing him our song,’ encourages Sid.

I compose my features to receive the worst and, as usual, get it:

‘Stomp on your momma,

Stomp on your pa,

Stomp on everybody

With a yah, yah!’

‘It sounds better with his guitar plugged in,’ says Sid. My first instinct is to say that I would prefer it with the little bleeder’s finger jammed up a light socket but I control myself. Criticism is always better received if it is constructive.

‘It’s a bit violent, isn’t it?’ I ask.

Sid takes another swig of tea and wipes his mouth with the back of his hand.

‘Exactly, Timmo. That’s what we in the business call the difference factor. You take all the kids singing at the moment. Not only are they older than Jason but they’re all singing ballads. I see Jason as the first of the mini-bopper neo-decadents.’

‘Yerwhat?’

‘A seven-year-old Mick Jagger.’

It takes me a few moments to come to terms with this idea but when I see the pout on Jason’s thick little lips – not as thick as they would be if I had my way – I begin to get Sid’s drift.

‘Blimey!’

‘Yeah. You remember how the Stones made the Beatles look like a load of fairies? Well, Jason is going to make David Cassidy and Donny Osmond look like Hansel and Gretel.’

‘My best friend called Gretel,’ interrupts Gretchen who has appeared with a plate of charcoal doorsteps which might once have been bread. ‘You like her. She big girl.’

‘Belt up, shagnasty,’ says Sid, unkindly. ‘Why don’t you push off and put the porridge through the mincer?’

Gretchen must be doing badly at the Clapham Junction College of Commerce because she smiles happily and bears the vat of porridge away, humming what sounds like an old Slobovian sea shanty.

‘I think your mother must have taught her to cook,’ says Sid wearily. ‘She works on the principle that the quickest way to a man’s fart is through his stomach.’

‘Very funny, Sid,’ I say, humouring him. ‘But do you really think that the market is right for a hard rocking seven-year-old?’

‘He’ll come right through to the mini-market,’ says Sid. ‘He speaks their language. He is one of them. Not a manufactured product forced on them by their mums and dads.’

‘He’s a manufactured product forced on them by us.’

‘Exactly, Timmo. That’s the important difference. He’s a rallying standard in the battle against parental conformity. The leader of the mini-bopper rebellion.’

I look at Jason who has one finger wedged up his hooter and is stirring circles in the sugar bowl with another and ask myself: can Sid be right this time? It is obvious that he has been getting ideas from the magazines in Doctor Naipaul’s waiting room but that has never been a guarantee of success in the past.

‘I’m still sceptical, Sid,’ I say.

‘Well, you’d better go and see a doctor,’ says Sid, screwing up his eyes in distaste. ‘Don’t talk about it at the breakfast table. It puts me right off my kipper.’

‘No, Sid,’ I say wearily. ‘I meant that I’m not convinced you’re right.’

Sid stands up, ‘You don’t have to take my word for it. I’ve entered Jason for the vicar’s kiddies talent contest. You wait till you see what he does to them down there. It’ll be an ideal test run. After that it’s the big time. Eh, Show Stopper?’

Jason tries to nod but his finger is still up his hooter and he nearly does himself a nasty injury.

‘What are you going to call him, Sid?’

Sidney switches on his ‘I’m so clever I might kill myself’ expression.

‘Plain Jason,’ he says.

‘I don’t get it,’ I say. ‘I mean, he is plain but do you want to remind every–’

‘If you weren’t so stupid I would think you were taking the piss,’ says Sid.

‘Uncle Timmy, very stupid,’ says Jason.

‘What I meant–’ Sid hits every word like it is a nail. ‘What I meant is that we are going to call him Jason. Jason all by itself. Jason nothing. It’s his real name, see? Very natural, very genuine. It’s a wonderful gimmick.’

‘I prefer Jason Nothing,’ I say.

Sid controls himself with difficulty. ‘You keep your preferences to yourself and help Jason off with his suit. I’m going to see about a group that could be very big. If I’m not back by four you’ll have to take Jason down to the church hall. And check that the sockets fit the plug on his guitar. They’ve got some terrible old stuff down there.’

Marvellous, isn’t it? With all my looks and personality I end up as dresser to a six-year-old kid whose nose runs faster than a Derby winner. I would not mind so much if Jason was not such an uncooperative little basket. He refuses to change at the church hall and throws a paddy because two of his sequins fall off coming down the stairs. Rosie is out on business so I have to sew the bleeding things on. I have just finished doing this when Jason wants to do potty and I find out I have sewn his trousers to his pants. This piece of information costs me another five sequins and twenty minutes during which my lips are jammed together tighter than a novice nun’s knees at an Irish funeral party.

By the time I have finished it is a race against time to get to the church hall before the Vicar’s frolic starts.

‘Uncle Timmy catch it when my dadda gets back,’ says Jason happily.

‘Little Jason catch a bunch of fives up his bracket if he doesn’t button his lip,’ I hiss. ‘Now, get a move on or we’re going to miss the bus.’

You would not believe it, but the little basket has the gall to throw a tantrum because he is not travelling by chauffeur-driven Rolls. God knows what Sidney has been telling him. I feel a right berk standing in the bus queue with Jason in his ridiculous clobber. He makes a toreador look like one of those skinheads who wanders down Oxford Street chanting ‘Hairy Krisnan’.

The bus conductor is not over-thrilled to see him either.

‘You going to bring the organ on as well, mate?’ he says to me. ‘You can take him on top if you like. There’s an old girl up there with a bunch of bananas.’

I ignore these crude attempts at humour and try to avoid the other passengers’ eyes as I cradle Jason’s guitar on my lap. He may be the answer to every five-year-old’s prayers but he is not doing much for the senior citizens huddled around me. They watch him like snakes being offered a glass rat for dinner. The Vicar does not exactly cream his cassock either.

‘I’m afraid the fancy dress party was last week,’ he says, nervously.

‘Belt him, Uncle Timmy,’ says Jason in a loud whisper.

‘This talented little chap is taking part in your contest, Vicar,’ I say evenly. ‘I’m sorry we’re a few minutes late.’

‘Jason Noggett, is it?’ says the Vic, going down his list. ‘I don’t think I’ve seen you or your wife since the wedding.’

‘I’m not married,’ I say.

The Fire Escape’s face clouds over. ‘Oh dear. I’m afraid that only those relationships that have been sanctified by the Holy Sacrament can offer up their fruit for inclusion in our talent contest.’

For a moment I think he is talking about a vegetable show and then I get his drift. ‘I’m the boy’s uncle,’ I say.

The Vicar looks much happier. ‘Of course. How silly of me. It’s so easy to jump to conclusions these days, isn’t it?’

‘How long before he goes on?’ I ask. I never feel comfortable talking to holy men. I think it goes back to when I was a kiddy and could not understand why they were dressed up as birds.

‘He’ll have to go on right at the end,’ says the Vic. ‘I’ve made out a list and I can’t change it now.’

‘Top of the bill,’ says Junior Monster, showing the first signs of pleasure he has evinced all afternoon.

‘It’s all harmless fun,’ says the man of God, realising that he has got ‘star or bust’ material on his hands. ‘Nothing too serious. I got the idea from one of those television programmes.’

I am getting ideas myself, but from a different quarter. One of the ladies present, presumably a mum, is definitely in the knock-out class. Slim, but with nice knockers and a wistful expression that makes me want to defend her against dragons and people like me. She has her arm resting on the shoulder of a kid wearing specs and long velvet shorts. The kid looks terrified, maybe because he is scared that his cello is going to fall on top of him. He holds his bow like a character in a fairy story defending himself against a giant spider. Poor little sod. He has obviously got no chance in the competition and is scared to wetsville about going on the stage.

I catch mum’s eye just as the Vic, hurries off to investigate a reported stabbing in the ladies – I noticed a geezer frisking the kids for weapons as I came through the door.

‘Have a shufti at the opposition, Jason boy,’ I say giving my tiny charge a gentle push in the direction of the stage, ‘– and don’t use language like that in the church hall!’ It may have been a silly place to leave a pile of hassocks but there was no need for him to say that. I don’t know where the little bastard gets it from.

‘Kids today!’ I say in my best ‘over the garden wall’ manner. ‘Little devils, aren’t they?’

‘There’s a lot of high spirits about,’ says Pablo Casals’s mother. She has one of those posh voices that suggests she lives in one of the houses facing Clapham Common. We live in a house that overlooks Clapham Common – completely.

‘When’s your boy going on?’ I ask.

‘Right at the end. It’s very nerveracking, isn’t it, William?’ William gulps and nods miserably. It’s a shame really. She should never have brought him. I know these upper class birds. They reckon they ought to get involved in the community and go around forming committees and parent teachers’ associations. Their kids go to state schools and their husbands hand out glasses of sherry and talk about community spirit. When the value of their house has trebled they sell up, move to Hampstead and send the kids to public school. They do a nice tea, though.

There is a burst of jeers and whistles from behind a curtain and a kid runs past wearing a bow tie and a top hat. He is in tears and is closely followed by a mother figure.

‘They did what with your balls?’ I hear her saying as they disappear from sight.

I take a peep through the curtain and – blimey! – I am glad I don’t have to go out there. They make the average Crackerjack audience look like Parkhurst lifers. I can hardly see beyond the first three rows for the pall of smoke and the kids are hopping about like a flea circus on acid. The stage is littered with orange peel and coke cans and the Vic is waving his arms about like it is the first heat of a semaphore contest.

‘Children, I appeal to you!’ he shrieks.

‘No you don’t, Baldy! Push off!’

‘What a load of rubbish!’

‘Why are we waiting!’

I step back from the curtain and shoot a quick glance at Jason – I would prefer to shoot a bullet but you can’t have everything you want in life. If the little bleeder can’t get this lot going he might as well jack it in immediately. I hope the Vic has the hall insured.

‘William Blenkinsop, William Blenkinsop! If I’d have known Miss Trimble’s mother was having her varicose veins done today I’d have put the whole thing off for a week.’

The poor old Vic is clearly going to pieces faster than flaky cod. William Blenkinsop has turned the colour of cold suet and is led out onto the stage by his mother carrying a chair. A chorus of wolf whistles suggests that some of the kiddies present have very mature tastes. I even think I hear a shout of ‘get ’em orf!’ but it must be my imagination.

‘What is first prize?’ Jason’s evil little eyes glint with anticipation. He obviously reckons it is all over bar the shouting.

‘Quite an ordeal for the boy, Mrs Blenkinsop,’ I say in my best Dixon of Dock Green voice.

‘Yes. I wish – perhaps I shouldn’t – oh, I don’t know.’ She leans forward nervously and I gaze sympathetically at the soft swellings in her fisherman-knit sweater. I wonder if I slid my arms round her and – no, it probably wouldn’t. People have such different ideas when it comes to offering comfort.

‘William Blenkinsop is going to play–’ There is an ugly pause while it occurs to everyone that the Vic has no idea what W.B. is going to play.

‘With his willy!’ shouts a child with a big future on late night chat shows. I can feel the glow of the Vic's cheeks from where I am standing. He mouths desperately into the wings.

‘Bach.’

‘Woof, woof!’ bays the audience.

Mrs Blenkinsop stiffens beside me and for a moment I think she is going to dash on the stage and yank William off. I have not heard a worse reception since Dad played us the last wireless he nicked from the lost property office.

‘Poor kid,’ I breathe as William licks his lips and prepares to play the first few chords. His eyes are closed and it is only the movement of the bow that tells us he is wanging away. The row is so great you can’t hear anything. Then, slowly, the music starts coming through. I don’t know a cello from a pregnant fiddle but it is obvious that the kid knows how to play the thing. The audience stop giving him the bird and start to listen. By the time the last note has wafted away into the rafters you could hear a pin drop. There is a moment’s pause and then lughole-shattering applause.

The only person not clapping is Jason. He looks about as happy as Ted Heath at a miners’ rally.

Out on the stage, William Blenkinsop bows stiffly and walks towards his highly chuffed mum.

‘OK Super Star,’ I say to Jason. ‘Now’s your chance to make history. Get out there and sock it to them.’ I take a last look at him and, of course, the stupid little basket has forgotten to do up his zipper. I give it a savage tug and – oh dear! The whole thing comes away in my hand.

‘What you doing!?’ shrieks Jason.

‘It doesn’t matter. You’re all right. Get out there. I’ll plug you in.’ His trousers are very tight and nobody would recognise his willy wonker if he painted it in day glo paint.

The Vic bustles up, looking a shade happier. ‘Jason Noggett, isn’t it?’

‘Just Jason.’

‘And he’s doing an impression of someone?’

‘No, he’s being himself,’ I say. ‘He’s going to sing an original composition entitled “Stomp on your momma”.’

The Vic does not look as if this is the best news he has had since the second coming but nods and shambles onto the stage with his silent lips rehearsing the words to come. We follow him.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.

Вы ознакомились с фрагментом книги.

Для бесплатного чтения открыта только часть текста.

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера:

Всего 10 форматов