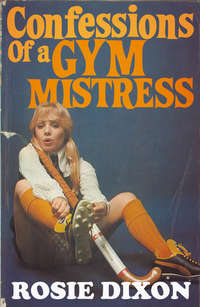

Confessions of a Gym Mistress

“Don’t be so defensive!” I tell him. “We all make mistakes.”

“Ze died vere ze lay!” screams the waiter. He starts pulling the side plates off the tables and hurling them towards the kitchen.

“Boumf! Boumph!”

“Do you want to stay?” says Geoffrey.

“Are you mad?” I say.

“No, but I’m a bit worried about him.” Geoffrey stands up and clears his throat. “We are leaving now,” he says. He might be repeating “How now brown cow”.

The waiter picks up a knife.

“Come on, Geoffrey!”

“Egon Ronay will hear of this.”

“Geoffrey!” I will remember that terrible man standing at the door and shouting “Schweinhunds!” after us till my dying day—in fact, I thought it was going to be my dying day.

“That was a bit thick,” says Geoffrey as we drive away. “Did you hear what that chap said?”

“Yes. He said ‘Schweinhunds!’”

“No. I mean about reporting us to the Race Relations Board.”

Marvellous, isn’t it? Unless you watched television all the time you could be excused for wondering who won the war.

“I need a drink after that,” I say.

As it turns out, this is my second foolish suggestion of the evening. Spirits play havoc with me on an empty stomach and Geoffrey makes me bolt back a second enormous scotch in order to “get it in before closing time” as he puts it.

“Do you fancy a packet of nuts with it?” he says. “They have eighteen times the protein value of steak, you know?” Something tells me that I can say goodbye to my supper.

“You need a bit of steak for that eye, don’t you?” I say.

“It’s much better now,” says my lark-tongued cavalier. “It’s no hardship looking at you through one eye.”

“You mean, it would be even better if you couldn’t see anything?”

“No! Rosie, why do you have to take everything I say the wrong way?”

“Because that’s the way it comes out,” I say. “Ooooh! I felt quite funny then. I think I’d better sit down.” It must be the scotch.

“I felt funny when you touched my arm like that,” breathes Geoffrey, sinking onto the moquette beside me. “Oh Rosie. I fancy you, rotten.”

“Well, that’s the way I feel at the moment,” I tell him. “I think I’d better go outside.”

“If you want to use the toilet, there’s one in the passage. I saw it as we came in.”

“Thank you, Hawkeye,” I say. “But I don’t think that will be necessary. You’d better take me home.”

We get outside to the car and, thank goodness, Geoffrey’s eye does seem to be a lot better. Just as well because the cool air hits me like a slap in the face and I hardly know what I’m doing.

“Comfy?” says Geoffrey as he shuts the door. “You wait till I turn the heater on. Then you’ll be really snug.”

He is not kidding! After about five minutes I feel as if I am sitting in a microwave oven. Geoffrey is talking to me about teaching but I just can’t keep my eyes open—I believe that lots of people have this trouble with Geoffrey. When I wake up it is because the engine has been turned off.

“Are we home?” I ask drowsily.

“Not quite,” says Geoffrey. “I brought you up to the common because it’s such a beautiful night.”

A glance out of the window shows that Geoffrey is not the only nature lover in North West London. Cars are parked all round us and inside them I can see the shadowy outlines of struggling figures—no doubt fighting to get a better view of the pitch darkness.

“It’s raining,” I say.

“I like rain,” says Geoffrey. “I think it’s very romantic. Water turns me on.” He proves it by trying to slide his hands up my skirt.

“Stop, cock!” I say wittily. “What are you trying to do? I thought you were taking me home?”

Geoffrey transfers his attentions to my breasts and one of my blouse buttons hits the windscreen.

“If you start teaching down in the country I won’t see you,” he pants. “I want you to know how I feel about you.”

“I’ve no problem knowing that,” I say, wishing he could be a bit gentler with his hands.

“Do you remember that time up the tennis club? Let’s do that again.”

“I don’t know what you’re talking about,” I say. Of course, I do remember but I don’t like to think about it. I mean, there was something funny in the fruit cup and Geoffrey took advantage of me—at least, he tried to. I’m still not certain what happened before he was sick behind the roller. As anybody who has read Confessions of a Night Nurse must know I am not a girl of easy virtue who bandies her charms about. I have a romantic nature but I try not to let it go to my head—or anywhere else.

“Just kissing you isn’t going to do any harm.”

Geoffrey is right, of course. There is no sense in being ridiculously prudish. We have known each other for some time and after Natalie’s remarks I am glad to find that I can arouse some feelings in the man. Also, the whisky is making it difficult for me to say no—that and the fact that Geoffrey’s mouth is firmly clamped over mine.

Oh! I wonder where he learned to do that? I always remember Geoffrey as a rather useless kisser. Perhaps Raquel Welchlet has been giving him lessons? The thought makes me determined to demonstrate that big sister knows best.

“Oh, Rosie!” The inside of the windows is beginning to steam up.

“Geoffrey! Please!” Without me realising what was happening he has raided my reception area. How awful that I am so befuddled with drink and hunger that I am practically powerless to resist him.

“That’s nice, isn’t it?”

“Geoffrey!” Now the condensation is running down the windows in rivulets.

“Feel how much I want you.” Geoffrey takes my hand and guides it to—OH! This is too much! Can this be the boy who shyly pressed a cucumber sandwich into my fingers at the Eastwood Tennis Club Novices’ Competition?

“Geoffrey!!”

“I must have you!” Geoffrey presses something between my legs—I mean, presses something situated between my legs—I mean, presses a lever situated on the floor between my legs—and the back of my seat drops down to the horizontal position. Hardly have I realised what is happening than Geoffrey is trying to scramble on top of me. I have never known such a change come over a man. It must have been that German giving him ideas.

“Are you mad, Geoffrey!?” I screech.

“Mad with love!” Somehow—don’t ask me how he manages to do it—the great idiot gets his foot hooked in the driving wheel. The horn lets out a high-pitched shriek—and then refuses to stop.

“Get your foot away!” I shout.

“I have!”

One of the good things about a nurse’s training is that it teaches you how to handle yourself in an emergency: take a long, critical look at the situation and then—panic.

“You’ve turned the ignition on!”

Geoffrey turns off the ignition and immediately the horn stops and smoke starts billowing out of the front of the car. He turns on the ignition and the smoke dies down while the horn starts again.

“Do something!” I scream. All around us I can see people reacting to the noise and one or two cars switch on their lights and start to pull away.

“You’d better get out!” shouts Geoffrey. He is pressing every switch and knob on the dashboard and I hear something making a spluttering noise like a fuse burning down. “The wiring must have shorted,” he yells.

I don’t wait to hear any more but start scrambling out of the car. Unfortunately, for some reason that escapes me, my tights are round my ankles and I am blinded by the headlights of a car that is pulling away. How embarrassing! I try to pull my skirt over my knees and fall down as I hobble towards the protection of some bushes. This is the last time I will ever let Geoffrey Wilkes take me out to dinner.

I have just found myself face to face with a middle-aged man wearing a plastic mac—and, as far as I can make out, nothing else—when I hear a familiar wailing noise. A police car, with light flashing, is bowling over the pot holes. I had only intended to pull up my tights and then return to help Geoffrey but, maybe, I had better wait and see what happens. The police car screeches to a halt beside Geoffrey’s car and two men jump out. The noise of the horn is still deafening and the smoke like that on a Red Indian party line.

Oh dear! One of the policemen has a breathalyser in his hand. I recognise it because I thought it was something else for a minute.

“Don’t do that!” I whisper to the man in the plastic mac. What a disappointing evening this has been. It just shows what happens when you look forward to something too much.

CHAPTER 2

“What time did you get in last night?” says Mum.

“Two o’clock,” says Natalie.

Needless to say, the question was addressed to me.

“We had a bit of trouble with the car,” I say truthfully. “I thought I’d better see it out with Geoffrey.”

“Oooh. You saw it out, did you?” says Natalie.

I ignore this piece of tasteless crudity and pop another piece of Ryvita into my mouth. For all I know the car may still be there. At least, the police silenced the horn before they took Geoffrey away. I remember how upset he sounded when they pulled all the wires out from underneath the bonnet.

That was at midnight. It took me two hours to get away from that horrible man and walk home. I have heard about people like him but I never thought I would be chased through a cemetery by one of them. I never thought people got up to tricks like that in cemeteries, either. Some of the things that were going on you would not believe if you were warned about them in the Sunday papers.

“The post is here,” says Dad. “There’s a big one for you, my girl. It must be your cards.” He drops a large buff envelope in front of me.

“I expect it’s the prospectus,” I say, trying not to let my excitement show as I slip my knife under the flap.

It is indeed. ‘St Rodence Private School For Girls, Little Rogering, Nr. Southmouth, Hants.’ There is a picture of a big house set amongst trees and rolling countryside, and an embossed coat of arms.

“Looks like a lunatic asylum,” says Dad.

Natalie laughs like he is Jack Benny.

“You recognise it?” I say. Once again, I can see that Dad is on the point of revealing that he has no sense of humour and it is as well that Mum steps in.

“Nice countryside, dear.”

“That’s one of the things that appeals to me,” I say truthfully.

“And having Southmouth so near,” says Natalie snidely.

“Perhaps you would care to elaborate on that remark?” I say grandly.

“Eeeoh I seeay,” minces Junior Nausea. “Fraytfully sorry and all that. Actually, you know, I was referring to the proximity of all those jolly jack tars. Do I make myself plain?”

“You don’t have to bother,” I say. “Somebody beat you to it.”

“Now, girls. Let’s have none of that.” Mum intervenes again. “If Rosie wants to go into teaching it’s up to us to give her all the support we can. Right, Harry?”

“Uum.” Dad sounds about as happy as Ted Heath finding that someone has locked up his organ and thrown away the key.

“There’s fourteen teachers,” I say. “And a broadly based curriculum.”

“That’s nice,” says Mum. “Your Aunt Enid used to play one of them.”

“What’s all this Oxon business after their names?” says Dad.

“Probably means they’re stupid,” says my pathetic sister.

“Don’t be an idiot,” I say. “B.A. Oxon means they’ve got an agricultural degree.”

“What’s the point of that at a girl’s school?” says Dad.

“It is in the country,” says Mum.

“They teach them to be milkmaids,” says Natalie.

I shut out their voices and read on about the acres of playing fields and the entrance scholarships won to Cheltenham Ladies College and Benenden. There is also a note from Penny:

“Dear Rosie,

Here is the official story. Don’t believe a word of it. The prospectus has not been reprinted for years. Half the playing fields have been sold as a building site and the left wing of the school—you can’t see it in the photograph—was blown down in the last gale. Luckily it had been evacuated after the school inspector fell through the floor—or ceiling—or both, dependent on which way you look at it.

But don’t let me put you off. The staff aren’t as bad as the sisters at Queen Adelaide’s and though the pupils are worse than the patients I’ve found a few very acceptable compensations—details when I see you! After receiving your letter I told Miss Grimshaw that you might be interested in the job and she is expecting a call. Hope this is O.K.? Must go now as I have a man hanging on for me—to the window sill, actually. Ho, ho, just my little joke—write soon. Love, Penny.”

“What does the letter say, dear?” asks Mum.

“Says I’ve got to get in touch with the headmistress,” I say.

“Gym mistress,” says Dad, shaking his head. “I just can’t see it somehow.”

I think Dad may be right but I don’t let on, of course. By a strange coincidence, I am on the point of picking up the telephone to call Miss Grimshaw when it starts ringing.

“Hello, it’s me,” says Geoffrey. “Are you all right?”

“No thanks to you and your Japanese wacky racer” I say coolly. “You know I had to walk all the way home?” I am expecting a profuse apology from the Chingford amateur rapist but I don’t get it.

“You were lucky,” says Geoffrey. “They’ve only just let me go.”

“It’s your own fault,” I say. “You should have zipped yourself up before you got out of the car.”

“It wasn’t only that,” groans Geoffrey. “They found your lipstick and compact in my blazer pocket. I’ve never been so embarrassed in my life. They thought—they thought I was some kind of pervert.”

I have never heard it put as strongly as that before. Poor Geoffrey, how very unpleasant.

“You should have told them about me,” I say. I am always ready with any offer of help short of actual assistance

“I did,” says Geoffrey. “But you weren’t there, were you? That made it even worse. Apparently there’s been some sex maniac up there, terrorising courting couples.”

“You don’t have to tell me that!” I scream. “Who do you think chased me through Chingford Mount Cemetery?”

“That’s terrible!” Geoffrey sounds comfortingly horror-struck. “Why didn’t you call a policeman?”

“Because there wasn’t one! They must all have been helping drag you back to the cells.”

“Oh dear. It had been quite a nice evening up until then, hadn’t it?”

“How did the breathalyser test go?” I ask.

“Positive.” Geoffrey shudders. “That was horrible too. They take your blood, you know. It’s not just a question of blowing into that bag. I took one look at the hypodermic and passed clean out. When I woke up I was covered in blood.”

“Geoffrey!”

“I’d banged my nose on the counter as I went down.”

“That’s terrible, Geoffrey. Are you all right, now?”

“My nose has stopped bleeding, yes. Now it’s just the charges.”

“Charges?”

“Drunken driving, gross indecency and causing a public disturbance. I think they might drop the last two if I buy them a new mat. I bled all over the last one.”

I am speechless. Geoffrey deserved some reprimand for leaving me alone at the mercy of that terrible man in a plastic mac—he kept telling me he was a bank manager, I wonder why?—but this is surely too much.

“What did your mother say?” I ask.

“She’s terribly upset. She’s been to see a solicitor and made me an appointment with a psychiatrist.”

Typical, I think. With Mrs Wilkes everyone is guilty until they are proved innocent. After that they are guilty again.

“I don’t know what to say, Geoffrey,” I bleat. “If there’s anything I can do to help you must let me know—send you a cake, that kind of thing.”

“Well, I—er—I don’t really know how to ask you this but I was hoping you might give evidence at the trial, if it comes to that.”

“Geoffrey, you know I’m in the middle of trying to get a job as a school teacher.”

“Yes, but—”

“And at a private school, too. It might be different if it was a comprehensive.”

“But without you, Rosie, there’s no one to prove that I wasn’t—that I’m not—”

“It’s not the end of the world,” I say soothingly. “People are much more broad-minded about sexual abnormality these days. Of course, there may be a few eyebrows raised at the tennis club but they’ll soon get used to the idea. You may even find that it takes the pressure off your tennis. You won’t be worrying about your game so much.”

“But, Rosie—”

“I must go, Geoffrey. I’ve got to ring the headmistress about this job. You know how important it is to me. Good luck with the—with everything. Give my regards to your mother.”

“She’d like to have a word—”

“I wouldn’t bother to ring up in the next few days because we’re having the house rewired and the phone is being disconnected.”

“But you don’t—”

“Goodbye, Geoffrey. Thanks for taking me out.” I put the phone down quickly and start dialling the St Rodence number. Whatever happens, I must not let Geoffrey’s misfortunes undermine my confidence.

The number rings for a long time and I am just beginning to wonder if I have the right one when the dialling tone stops and a fruity voice says,

“Geood morning. St Rodence School. Headmistress’ secretary speaking.”

“Good morning. My name is Rose Dixon. I think Miss Grimshaw is expecting me to get in touch with her regarding a j—a position she needs filling.” “Job” doesn’t sound very posh, does it?

“Heold eon, please.” There is a rustling of papers followed by what sounds like a bottle falling over and a muffled oath. “I’m seorry to keep you waiting. You’ve caught us in the middle of elevenses.” I hear a belch and a burst of uncontrolled laughter.

“I’m sorry. Would it be better if I rang back?”

“Neo, it’s quite all right. I’m just looking for the appointments book. Ah, here it is. Underneath this—” The voice exhibits signs of strain and there is a sound like a heavy body falling to the floor “—pile. Neow, where are we? Ah, yes. How does tomorrow suit you?”

And that is how, the next day, I find myself sitting on the 10.32 out of Waterloo. It was originally the 9.12 but that had to be combined with the 7.37 when the driver went off on a cheap day trip to Clacton. It must be very difficult running the railways.

Little Rogering does not have a station and to get there you have to catch a bus from Pokeham which does not have a station either but is where the bus from Fudgely drops you. I am glad that Penny is meeting me with a car.

The journey down is uneventful and I am not attacked by anyone. You may think that I am being fanciful but it is amazing how often men expose themselves to me. I think I must throw out some kind of electrical impulse that activates the front of their trousers. It is just like garage doors sliding open sometimes.

The countryside outside the window is rolling and wooded and I get quite excited as I see all those exotic names I have only read about in divorce actions: Guildford, Godalming, Haslemere. I can’t really believe that a posh school like St Rodence will accept a simple girl from Chingford—or West Woodford as Mum prefers to call it. The whole thing is probably just a dream. Anyway, it will make a nice day in the country.

“Fudgely. Change here for Milldrew and all stations to Rotting Parva.”

Here already? It seemed only a second ago we were pulling out of Petersfield. I grab my bag and stumble out into the corridor. Beside me are two girls wearing gymslips. It is funny but they look just like the two girls wearing tank tops and sequined hot pants who were waiting outside the toilet when I wanted to get in. Not quite as much eye make-up, though.

“Oh, well, back to the crummy old dump,” sighs one of them. “Still, at least we’ve got a few memories.”

“You bet,” sighs the other one. “You can’t beat the Yanks when it comes to lobbing the lolly about.” They push in front of me and jump off the train while it is still moving. I can hear them shouting for a taxi as they run out of the station.

“Rosie, darling!” Penny comes out of the refreshment room with a glass of gin and tonic in her hands and kisses me on both cheeks. She is very upper class like that. “I never expected the train to be on time. Let me look at you. You look ghastly! Where did you get that suit from? You don’t look old enough to have been in the land army.”

“I got it specially,” I say, feeling hurt. “I thought I’d better turn up in something fairly sober.”

“Sober!?” Penny knocks back her drink and hands the glass to a surprised porter. “That’s enough to put you off the stuff for life. You could be mistaken for a member of the staff wearing that.”

“That’s the idea,” I say.

“I know, I know. I was only teasing. Grimmers will love you—if she can see you. She’s been knocking it back a bit lately.”

“She drinks?” I say.

“Like a fish. You can’t blame her though. My God, I’d drink if I didn’t have sex to keep me going.” Penny smiles at the man on the barrier and pushes me towards a battered sports car. “You kept your ticket, didn’t you? Good. You can use it again next time.”

“If there is a next time,” I say.

“Don’t worry, darling. At this place you usually get the job by bothering to telephone. There’s a chronic shortage of teachers you know. Most of them have got more sense than to work at Dothegirls Hall.”

“Dothegirls Hall?”

“You remember Dotheboys Hall? It was in Nicholas Nickleby or Great Expectations or Biggles Flies East—I can’t remember which. I’ve stopped taking English this term.”

“English? I thought you were games mistress.”

“Oh I am, but you have to be flexible here. When Miss Carstairs ran off with the man who came to mend the boiler I had to fill the gap that he was filling—if you know what I mean.” Penny turns to me and winks and we narrowly miss a furniture van.

“Is there a large turnover of staff here?” I ask.

“Yes and no,” says Penny. “There are the elderly dead beats who stay here because they know they will never get a job anywhere else—and can’t be bothered anyway—and the dynamic young graduates who want to turn the educational system upside down and leave, disillusioned after two weeks.”

“Which lot do you fit into?” I ask.

“Oh, there’s a third category of escaped convicts, murderers and retired female impersonators—nice countryside, isn’t it?”

“Lovely,” I say. “I gathered from your letter that you’ve met a few locals?”

“Yes, the area isn’t badly equipped hunk-wise. One of my little chums hangs out over there. Do you want to pop in and say hello?” Penny indicates a collection of low, ramshackle buildings with a sign outside saying Branwell Riding Stables.

“I don’t think I’ve got time,” I say. “Miss Grimshaw is expecting me at twelve.”

“Don’t worry about that,” says Penny swinging the wheel over. “She’ll expect the train to be half an hour late. Anyway, I bet she’s already started glugging down her lunch. You don’t usually get much sense out of her after ten o’clock.”

“But—”

“Don’t worry, darling. This isn’t Queen Adelaide’s. We live life at a slower pace down here—oops! Did I get it?” I watch the chicken dive under the barn door and shake my head.

“This guy is called Guy Hark-Bach,” continues Penny, unperturbed, “I met him at the hunter trials.”

“Did they get off?” I ask.

“You’re terribly unspoilt, aren’t you?” muses Penny after a moments silence. “Come on, let’s squeeze a quick G. and T. out of the old horse dropping.”

I don’t know what she is talking about but I meekly follow her into a building that looks like a good pull-in for tennis court marking machines—like primitive.

“Penelope, mon ange, what scented zephyr wafts you into my aegis?”

For a moment I think that the fella must be speaking manx. Then I grab the peakless cap pulled low over the nose and the hounds-tooth hacking jacket and I realise it must be Penny’s mate.