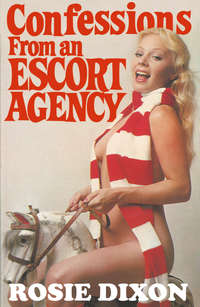

Confessions from an Escort Agency

‘Just about.’ Geoffrey shuffles from one foot to the other and makes funny faces as if he is trying to swallow something.

‘You are going to be in demand.’ Mum looks at me. ‘You’re lucky that Geoffrey has the time to spare to take you to the station.’

‘We’d better be going, I think,’ I say, before Mum can start calling the banns.

‘Yes.’ Geoffrey knocks the telephone off the table and dives down with Mum to pick it up. There is a painful crack of heads and I walk out and put my suitcase in the car. As I do so, Dad appears looking as if the cares of the world weigh heavily on his shoulders.

‘Are you coming or going?’ he says.

‘I’m going to stay in the country for a few days,’ I say.

‘Is it the holidays already?’ he says.

‘The school had to close down. It was all a bit of a—’

Dad holds up his hands. ‘Don’t tell me. I can imagine. You’re out of a job again, that’s what it boils down to, isn’t it?’

‘If you put it like that, yes,’ I say. Dad’s parents obviously never put him through charm school. He hasn’t even said ‘hello’ yet. ‘I’m going to discuss a new job with the people I’m staying with.’

Luckily, before I have to get involved in any embarrassing details, Geoffrey comes out of the house. ‘Evening Mr Dixon,’ he says, stepping into a flowerbed so that Dad can pass.

‘That’s one of my wallflowers you’ve got your foot on,’ says Dad.

‘Oh, I am sorry.’ Geoffrey takes another step backwards and sits down in the garden pool.

I close my eyes. This does not bode well for our trip to the station.

‘Don’t pull on that—’ Dad’s voice breaks off at the same moment as the head of the stone cherub that was standing beside the pool. Geoffrey tries to replace the head in a number of positions and then lays it on the bird bath the cherub is holding.

‘I’m awfully sorry,’ he says. ‘I’ll get you another one.’

I can see the whites of Dad’s knuckles as he clenches his fists. ‘Don’t leave the head lying there,’ he says. ‘It looks like John the Baptist saving Salome the trouble.’

‘Oh very good,’ says Geoffrey. ‘Did you hear that—?’ His voice trails away when he reads the expression on Dad’s face. ‘Sorry again, Mr Nix–Dixon. I’ll–er—’ Geoffrey trips over the brick edging to the garden path and throws his arms forward so that the cherub’s head describes a graceful semi-circle and shatters a cucumber frame.

‘Come on, Geoffrey. We must be going or we’ll miss the train,’ I say helpfully.

‘Get out!’ screams Dad. ‘Get out!!’

‘I’m sorry,’ says Geoffrey. ‘I’m terribly sorry.’ He tries to close the garden gate behind him and the catch snaps off.

‘Don’t touch anything!’ I beg him. ‘Whatever you do, don’t touch anything!’

Geoffrey is shaking when he gets in the car and he tries three keys before he finds the right one for the ignition.

‘She’s a bit stiff,’ he says. ‘I wish that damn fool hadn’t boxed us in behind.’

‘Careful,’ I say. ‘That’s—’ I am going to say ‘Dad’s car’ but after Geoffrey has backed into it there doesn’t seem much point. I don’t want to upset him unnecessarily.

‘Are we all right on that side?’ asks Geoffrey. I wrench my eyes away from the water seeping out of Dad’s radiator and shoot a quick glance at the car in front. Dad has heard the crash and is coming down the garden path – fast.

‘I think so,’ I say. As it turns out, I am wrong, but we only catch the car in front a glancing blow before pulling out into the middle of the road. ‘What’s the acceleration like?’ I ask. Fortunately, Geoffrey is able to show me, just as Dad lunges for the door handle.

‘Very good,’ I say.

Geoffrey glances in the rear view mirror. ‘Why’s that chap lying in the middle of the road, shaking his fist at us?’ he says.

‘I don’t know,’ I say. ‘Mind out, you’ll hit this milk float!’

‘Which milk float?’

‘The one you’ve just hit,’ I say, looking over my shoulder. Honestly, I have never left Chingford with a greater sense of relief. If we are going to have an accident I would much rather we had it somewhere other than on my own doorstep.

It soon becomes clear that Geoffrey is in a terrible state and not at all at ease at the wheel of the mighty Daimler. He is crawling along and at this rate it is obvious that we are going to miss the train. The rush hour traffic doesn’t help, either.

‘Don’t you know any short cuts?’ I say, beginning to get desperate. ‘You’ll find it easier in the side roads anyway.’

As it turns out, I am wrong. With cars parked all over the place it is very difficult to manoeuvre and we soon find ourselves going slower than ever. I am rather angry with Geoffrey for accepting my suggestion but I try and control myself.

‘We’ll have to get back on the main road,’ I say. ‘Pull out now! Come on!!’

‘But it’s a funeral,’ says Geoffrey.

‘It doesn’t matter,’ I say. ‘Come on, Geoffrey! We’ll be here for ever if you don’t get a move on.’ Still grumbling, he does as I tell him and we fall in behind the car which has the coffin in it.

‘Lovely flowers,’ I say. Geoffrey must be sulking because he does not say anything. Five minutes later, the hearse takes a sharp right turn and we carry on.

‘Try and make a bit of speed now,’ I say. ‘Surely you can overtake him.’

Geoffrey says something about back-seat drivers but he does as I say – Geoffrey always does as I say – and puts his foot down.

‘Well done,’ I say. ‘I think maybe, next time, you’d better do it on the outside.’

‘I thought he was going to turn right,’ says Geoffrey. ‘Ooops!’ We get past the fire engine all right and I look back to make sure that we have not given any of the men clinging to the side the brush off. I am most surprised when I see another Daimler clinging to our tracks – and another – and another!

‘Geoffrey!’ I say. ‘How awful. They’re following us.’

‘The police?’ Geoffrey stands on the brakes and I see the whites of the driver behind’s eyes as he tries to avoid going into the back of us.

‘No, the funeral party.’

Geoffrey looks over his shoulder and shares my view of the black hats, veils and sombre expressions.

‘Gosh! We’d better stop and tell them.’

‘There isn’t time,’ I squeak. ‘It’s touch and go as it is. Keep going and I’ll attract their attention.’

I should have said try and attract their attention. I have never met such a load of zombies. I wave my arms about and shake my head and point to the side streets and there is no reaction at all – apart from one woman who bursts into tears. The others just stare at me.

‘Here we are,’ sings out Geoffrey. ‘Damn! There’s a great queue of cars.’

‘Go up where it says “Taxis Only”,’ I say. ‘This is an emergency.’

Well, I must say. I am very disappointed in the attitude of the taxi drivers. I had always thought them such a bluff, cheerful lot, hadn’t you? The kind of people who would give you the shirt off their back in an emergency. The lot we bump into outside the station would not give you an old surgical support. I suppose it is unfortunate that five Daimlers follow us into the taxi rank but it is not our fault that people with suitcases start wrenching open the doors and climbing inside the minute they have stopped.

‘West London Air Terminal and step on it!’ I hear one of them shout.

‘’Ere! What do you think you’re doing!?’ says a large man with a red face and a luggage label fastened to his lapel. Before Geoffrey can open his mouth, the man starts dragging him out of the car and shouting ‘Bleeding minicab drivers!!’ Mini cab, I ask you! It’s ridiculous, isn’t it? The Daimler is built like a furniture van.

I am trying to say goodbye to Geoffrey when a very agitated woman dressed in black runs up to me and says, ‘Where’s my Dick?’

For a moment I don’t know what to say. I mean, I am a little overwrought and there are some very funny people about. Then it dawns on me. Dick must be the deceased.

‘I think he went up to High Holborn,’ I say. ‘You shouldn’t have followed us. We’re nothing to do with the funeral.’

For some reason the woman reacts very badly to this and tries to hit me with her umbrella. I know she is under strain but, really, it is a bit much with all the problems I have. Geoffrey is sinking to his knees under a rain of blows and all around me there are scuffles breaking out as the funeral party refuse to leave their cars, people try to scramble into them with suitcases, and cabbies assault the drivers. Sometimes I think that all this stuff about the British remaining cool in emergencies is blooming rubbish.

CHAPTER 2

In which Rosie visits an Oxford college and endures some disgusting experiences at the hands – and other things – of the Hon. Ward-Virgins and his friends.

Of course, the culmination of the whole sordid business is that I miss my train. I am absolutely furious about it and can hardly wait for Geoffrey to regain consciousness before telling him what I think of him.

‘I’ve tried to ring through but the phone is out of order and the next train doesn’t leave for an hour,’ I say. ‘Geoffrey, how could you? You sit there calmly bleeding into that handkerchief and my world has collapsed in ruins.’

I must say that Geoffrey is very good about it. When I have calmed down and the bleeding has stopped he gives his name and address to the police, collects all the pieces that have been broken off the car, and suggests that he drives me to Oxford.

‘You’ll probably be able to catch up with your friend at this party,’ he says. ‘Where is it? St Peter’s Hall?’

I am slightly worried by the prospect of Geoffrey cramping my style but on the other hand, beggars can’t be choosers, can they? Better to arrive encumbered than not at all. The journey to Oxford is quite remarkable in that we do not have any form of accident on the way. Not one teeny-weeny prang. Maybe it is this that lulls me into a sense of false security. I close my eyes and try to sleep but all the time I am thinking of the hundreds of years of tradition and noble breeding that I will shortly be part of. I do hope that I do not feel out of my depth and that Geoffrey does not say anything to let me down. Although he plays tennis for Eastwood Tennis Club and watches ‘Aquarius’, Geoffrey is not as intellectual as he would like people to think. We ask the way in Oxford and find that St Peter’s is between Woolworths and Mothercare and I begin to get goose pimples. Soon I will be setting foot on those flagstones mellowed by contact with the great minds of history. Who knows? – Perhaps Dudley Moore went here?

‘There it is.’

Geoffrey slows down and I suck in my breath. It is just as I imagined it would be: the gold-topped railings, the warm brick buildings, the window boxes full of flowers, the man with shoulder-length hair and a placard saying ‘The Senior Tutor is a Stupid Old Fart.’ – wait a minute! How did he get here?

‘Good, isn’t it?’ says Geoffrey. ‘Where shall I park?’ Half an hour later we have walked back to the street containing the college.

‘Just look at those windows,’ I say. ‘What beautiful sashes.’

‘They are nice,’ agrees Geoffrey. ‘I like the ones with the little dogs and the horseshoes.’

Would you believe that the stupid fool is looking in the window of Woolworths? Oh dear, I feel that he is going to be completely at sea once we get inside the college. We get back to the front gate of the college and Geoffrey puts down my suitcase.

‘Do you know where to go?’ he asks.

I do not answer at once because I am busy looking at a line of men lying against the wall. One or two are reading but most are staring into space. Very odd. We go into a little office and there is a middle-aged man with a bowler hat standing behind a desk.

‘I’m looking for a party,’ I say.

The man behind the desk looks at my suitcase. ‘Are you Fi Fi La Knocker?’ he says.

‘Most definitely not!’ I say. ‘What would a person like that be doing here?’

‘The cabaret for the Rugby Club smoker,’ says the caretaker.

‘That’s what you might call a party.’

‘I don’t think my friend would be going to that,’ I say. ‘She’s not very sporty.’

The caretaker laughs. ‘Neither are the Rugby Club. They haven’t won a game in three years.’

‘Are there any other parties that you know of?’ says Geoffrey.

Bowler Hat thinks. ‘I saw some crates of champagne piled at the bottom of Z staircase. Could be that the Hon. Ward-Virgins is giving one of his soirées.’

‘That sounds much more like it,’ I say enthusiastically. ‘Is there anywhere round here I can change? I’m afraid I missed my train and had to get a lift down.’

The caretaker looks me up and down thoughtfully. ‘We don’t have a lot of facilities for ladies,’ he says. ‘The Admissions Board turned them down flat.’

‘They obviously didn’t like flat ladies,’ says Geoffrey. I blush furiously. I was dreading Geoffrey saying something like that. How could he so demean himself in this temple of erudition?

‘Ho, ho. Very jovial, sir,’ says the caretaker. ‘A joke, eh, sir? Ho, ho. We don’t have many of those these days.’

‘What are those people doing, leaning against the wall?’ asks Geoffrey.

‘Don’t rightly know, sir. They’re either protesting about the quality of the collége food or fasting for the third world.’

‘What’s the third world?’ I ask.

The caretaker shakes his head. ‘I don’t know, miss. But it’s a phrase much used in the college these days. Second only to “fascist pig” in popularity, I would say.’

‘You’re very tolerant,’ I say. ‘Why do you allow that man to stand out there with that rude sign?’

‘He’s the Dean, miss.’ I am so amazed that I can’t think of anything to say. The caretaker comes round his desk and picks up my suitcase. ‘Yes, miss. Times have changed. Still, I think you’ll find that Mr Ward-Virgins keeps up the old traditions.’ He leads the way out into the courtyard and Geoffrey and I follow him.

‘I could groove on your flesh, baby,’ says the Dean but I pretend not to hear him. I knew this kind of behaviour went on at redbrick universities but it is a terrible shock to find that the ‘city of dreaming spires’ is not free from taint. Why have people turned their backs on the old values? It is a question I look forward to discussing with the Hon. Ward-Virgins. We have taken a couple of steps across the court when a first floor window shoots up and a man vomits all over one of those lying below. There are loud cries of ‘Well done, Bertie!’ and ‘Best tonight!’ Needless to say they do not come from the courtyard.

‘That’s the gentleman himself,’ says the caretaker respectfully. ‘His family have been throwing up out of that window for hundreds of years.’

I try to catch a glimpse of the Hon. Ward-Virgins but he is hauled back into the room and the window comes down on the shouts of the rabble below like a guillotine.

‘What a disgusting thing to do,’ says Geoffrey.

Once again I feel a hot flush invading my cheeks. What can Geoffrey Wilkes know of the traditions of ancient Oxford colleges? Anyway, I can remember when he disgraced himself behind a roller at the Eastwood Tennis Club Summer Ball.

‘Geoffrey, please!’ I hiss. ‘If you’re going to behave like that we might as well say goodbye now. I can’t stand any more unpleasantness.’

To my surprise, Geoffrey stops in his tracks. ‘Very well,’ he says. ‘Goodbye. If this is what you want, you can have it. I’d rather go back to Chingford.’

‘West Woodford!’ I hiss. But he has turned on his heel and is marching across the grass.

‘My God!’ exclaims the caretaker. ‘He be walking across Founders Lawn!’

‘That’s bad?’ I say.

‘Nobody walks on Founder’s Lawn save old Ben Clutterbutt who cuts it and he wears ballet shoes.’

Oh dear! Geoffrey has clearly committed a terrible boob. ‘Geoffrey—’ I call out. But, too late. I hear a shout from above and look up to see one of the young men decorating the chapel with toilet paper pointing angrily at my accident-prone friend.

‘’Ware turf-scuffers!’ he shouts. ‘Scrag the blighter!’

‘That’s put the cat amongst the pigeons,’ gasps the ancient retainer by my side. ‘That be young Mr Bellchamber, President of the Boat Club. They’re celebrating in the traditional way because the eight rowed over today.’

‘Rowed over what?’ I ask. I mean, it could have been a weir or a waterfall, or anything, couldn’t it?

Before the caretaker can answer, a crowd of oarsmen appear and surround Geoffrey. I know they are oarsmen because they are all carrying oars with which they bang Geoffrey over the head – all except one little man who looks around for a stick.

‘Duck him!’

Geoffrey is picked up and carried shoulder high to one of the most beautifully carved fountains I have ever seen. It is all nymphs and dolphins and things with spouts of water coming out of their mouths – not other places as you see in some statues.

‘Do look, Geoffrey,’ I say. ‘Isn’t that lovely?’

I don’t know if Geoffrey hears me, and it would probably not have made a lot of difference if he had. He is not very interested in sculpture.

SPLASH!! Geoffrey disappears under the water and a cheer goes up.

‘Row him out, fellows!’ Immediately the oars are slotted in amongst the pieces of sculpture and used as bollocks – or whatever those things on the side of rowing boats are called. It is terribly clever how they do it. The water froths and bubbles and Geoffrey is swept backwards and forwards by the threshing oars until a concerted heave flips him out of the fountain and onto the cobbles. I suppose it is rather cruel but you have to admire the technique – just like a bullfight.

‘You bullying swine!!’ shouts Geoffrey.

The caretaker sucks in his breath. ‘No sporting instinct,’ he hisses contemptuously. ‘They were using the flats of the blades, too.’

I blush for Geoffrey but there is no opportunity to have words with him. Pursued by jabbing oars he runs from the college and into the deepening dusk. The caretaker shakes his head and bends down to adjust a blade of grass. The incident is clearly closed. We continue our journey in silence and have entered a smaller court when my guide stops outside a heavy wooden door.

‘This is the domestic bursar’s cloakroom,’ he says. ‘You can change in here. The lock’s not very good but don’t worry, I’ll keep watch.’

He is as good as his word and in fact, even puts his head round the door on a number of occasions to make sure that I am all right. I am touched by such consideration and do hope that I am not causing the good man too much inconvenience. At one stage, when I am changing my tights, he begins to groan in a most alarming manner and I notice that his right hand is shaking fit to break off. Fortunately the spasm soon passes and he accepts gratefully the glass of water I hand him. Less fortunately, he jerks most of it over the floor before he can convey it to his mouth.

While I put the finishing touches to my make-up it occurs to me that I have taken a lot for granted in imagining that I will find Penny at the Hon. Ward-Virgins’ party. On the other hand I am certain that someone will know of her whereabouts and the chance to see how a real gentleman lives is one that I am unable to resist. Just a glimpse will be enough.

The caretaker shows me to the bottom of Z Staircase and I leave him breathing deeply with his head resting against his arm, and go up the narrow flight of stone stairs. The noise that greets my ears suggests that a party is in full swing and my senses quicken in anticipation. The day has been so full of unpleasant incidents that I feel more than overdue for a little pleasure.

I reach the head of the stairs and am about to approach the door in front of me when it bursts open and a man staggers out holding a champagne bottle. He raises it to his lips, tilts the last drops on to his chin and then sinks slowly to his knees and rolls down the stairs.

‘Are you all right?’ I call after him, but he does not answer.

‘Another wench, by God!’ The man looking me up and down approvingly is wearing a lace choker, a long velvet jacket and knee breeches. He is very handsome and his shoulder length hair hangs in ringlets. ‘I’ll plumb your flanks before the night is out,’ he says fiercely. ‘You’d better go and change, we’re nearly ready for the huntin’.’

‘I’m looking for my friend Penelope Green,’ I say, not really understanding what he is talking about.

‘’Spect she’s in there with the rest of the fillies.’ He leads me into the room and whispers into my ear. ‘Stay by the south wall.’ He winks and pushes me through a door leading off the main room. I only have time to catch a glimpse of a jostling group of young men swilling champagne and then the door closes behind me.

I am in a room with about half a dozen girls all in various stages of undress. A number of long white robes are hanging from the walls and it becomes obvious that the girls are changing into them. What rather surprises me is that they are stripping completely naked before doing so. There is no sign of Penny.

‘What’s going on?’ I ask.

‘We’re changing for the hunt, of course,’ says one buxom creature who is anointing the valley between her generous breasts with perfume.

‘The hunt?’

‘In the deer park. Don’t say you’ve never done it before? Who introduced you?’

‘My friend Penny invited me to a party here.’

‘Penny? Never heard of her. Still it doesn’t matter. You’re here, aren’t you?’

‘I suppose I am,’ I say. ‘Tell me, what happens?’

‘It’s not a question of “what”, it’s a question of how many times,’ says another girl.

‘It gives the young gentlemen pleasure, that’s the main thing,’ says a pretty blonde girl adjusting the fall line of her dress by raising it and letting it drop to the ground.

‘And it’s been going on for hundreds of years,’ says the first speaker. ‘Every time I take a tumble I feel like a part of history.’

The others nod in agreement and I feel a new excitement. What a stroke of luck. I love ritual and it looks as if I am going to take part in some.

‘You’ll have to show me what to do,’ I say. The other girls laugh and clap their hands to their mouths.

‘Lawks a mercy,’ says the pretty blonde. ‘You’re a bright spark and no mistake. You’ve no need to do anything. You just keep running, my girl. All the doing is taken care of.’

I would like to ask more questions but the door flies open and a young man with a shiny face and a glass of champagne sways backwards and forwards in front of us.

‘Right, jades! Your moment has arrived,’ he barks. ‘To the park with you and we’ll seek you out when we’ve quaffed another jeroboam of bubbly.’ He staggers across the room and unbolts a door which gives onto a flight of stone stairs. I catch a glimpse of a moonlit garden and then the exit is blocked by the escaping girls. Giggling and shrieking, they flee into the night. How exciting it all is. I can’t wait to start playing. ‘You’re slow, wench. Do you need any help to shed your garments?’

Before I can tell him to keep his hands to himself, the man has started to rip open my blouse! Like a food-crazed porker he exposes the ripe fruit of my breasts and buries his face in my bosom. I know I am probably being prudish but this does seem a little much. We have not even been introduced.

‘Hands off the merchandise, Rollo, the sale has yet to begin.’ My rescuer, for so he proves, is the good-looking man who greeted me when I arrived at the party. He seizes my attacker by the shoulders and sends him reeling out of the room.

‘Thank you so much,’ I say. ‘Tell me—’

‘Two minutes, no more,’ interrupts my deliverer. ‘Change swiftly. I can hold them back only with the greatest difficulty – myself included.’ He delivers a smacking kiss to each of my unprotected breasts and retreats from the room. A trifle forward, I think to myself, but his heart is obviously in the right place – to say nothing of another part of the body that thrust itself against me.