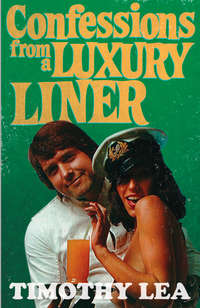

Confessions from a Luxury Liner

Confessions from a Luxury Liner

BY TIMOTHY LEA

Contents

Title Page

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Also available in the CONFESSIONS series

About the Author

Also by Timothy Lea & Rosie Dixon

Copyright

About the Publisher

CHAPTER ONE

‘Was it nice, Sid?’ I ask.

Clapham’s answer to Paul Newman grits his Teds like he has plans to make them retractable. ‘Watch it!’ he hisses. ‘Just watch it. I’m not telling you again.’

Readers of Confessions of a Private Dick will recall that my brother-in-law and partner, Sidney Noggett, ran into a spot of bother at the end of our career as C Men working for Mission E – or Emission as it was widely known in concentric circles at the Ministry of Defence. I will not spoil the story for those who have not read it by revealing the amazing details, but suffice to say that Sid’s distress was occasioned by an unsolicited sexual encounter – and there are not many of those flying around as far as Mrs Noggett’s little boy is concerned, I don’t mind telling you. Sid usually holds back from nooky the way a freshly sharpened hatchet rests lightly on half a pound of warm butter.

‘I’m not asking for the unpleasant details,’ I say.

‘Don’t ask for anything,’ says Sid. ‘Otherwise your lower lip is going to look like Idi Amin’s pyjama case. Anyway, what have you got to rabbit about? You haven’t heard from your precious Retchen, have you?’

‘Gretchen,’ I grit.

‘No doubt some horny Kraut is introducing her to his Frankfurter at this very moment,’ says Sid, clearly warming to the idea. ‘Oh yes, I reckon you can say “auf wiedersehen” to that little number.’

I try to look as if the idea is too blooming stupid to comment on but in my heart of hearts I fear that he may well be right. Gretchen went back to Germany three weeks ago and I have not heard a dicky bird since. Our bitter-sweet romance was not helped when the local anaesthetic I used to assist in its consummation sent my dick to sleep half a second after penetration. I would have cried if Gretchen had not beaten me to it. It was all so sad because she went home before I had the chance to introduce her to the full lustre of my cluster.

‘She’ll write,’ I say. ‘Don’t you worry.’

‘I’m not worried,’ says Sid. ‘Not about that, anyway. Of all the bleeding things I’ve got to worry about, your bit of Hun fluff is very low on the list.’ He takes a long sip of Mum’s tea and his face wrinkles in disgust. ‘Gordon Bennett! Can’t your Mum even make a cup of tea? Look at the brown rings round the inside of this cup. They’ve eaten into the china.’

‘Mum puts something with it to make it go further,’ I tell him.

‘This isn’t going to go any further,’ says Sid pushing his cup away. ‘Blimey, I wish I’d brought my clogged-up paint brushes with me. Stick ’em in this lot for a few minutes and you could paint the Mona Lisa with them.’

Sid and I are having a cuppa round at 17 Scraggs Lane, the ancestral home of the Leas, and we are supposed to be discussing our future. No sooner has my brother-in-law emptied the contents of his cup down the sink than my mother enters clutching a couple of letters.

‘I didn’t know people still wrote letters,’ says Sid. ‘Still, when it’s a choice between spending the money on a stamp or a few hundred British Leyland shares …’

‘There’s one from Germany,’ says Mum. ‘Quite a pretty stamp. You wouldn’t think the Germans would have a stamp like that.’

‘Here it comes,’ says Sid cheerfully. ‘The old brush-off, Kraut-style. Get your handkerchief out.’

‘Oh look,’ says Mum. ‘Somebody’s poured their tea leaves into the sink. What a waste. You can dry them and use them again mixed with dandelion leaves. I heard it on the wireless.’

‘That was for pipe tobacco, not drinking!’ says Sid. ‘No wonder it tasted so diabolical. That bleeding tom is always up against the dandelions.’

My finger and thumb are testing the contents of the airmail envelope. It does not seem over-thick for a passionate love letter. Perhaps I would be better off reading it in the privacy of my own very small room.

‘Read us out the fruity bits,’ says Sid. He snatches the envelope and holds it under his hooter. ‘Phew! Eau de Sauerkraut. She must have been off with some bloke when she posted this.’

‘She was a nice enough girl,’ says Mum. ‘For a foreigner, that is.’

‘I know, Mum,’ I say. ‘Their ways are not our ways, are they?’

‘That’s exactly what I always say,’ says Mum.

‘I know it is,’ I say wearily.

‘He’s taking the piss,’ says Sid. ‘I think love has coarsened him.’

‘That’s not nice,’ says Mum.

I suppress a sigh and tear open the envelope. I do wish Sid would spend a bit more time in his trendy Vauxhall pad with my sister Rosie and his two delightful children, Jason and Dominic. He always said how much he loathed Scraggs Lane when he was forced to live here. Now he never stops hanging about the place.

‘Dear Timmy,’ I read. ‘I hope you are well. I am sorry I am not writing more soon but there is very much happening when I arrive home. I have seen many old faces. One of them is Horst. I do not remember if I tell you around him. He is maybe the reason why I leave home. He has told me that he misses me very much and I think that I miss him, too. At Christmas we become engaged so I will not be coming back to England.’

I let the letter drop to waist level and Sid does not have to go to night school to read my expression. ‘Like I said, eh?’ he says cheerfully. ‘The big elbow. You can’t say I didn’t warn you.’

‘Thanks,’ I say.

‘Is there someone else?’ says Mum. She sounds quite perky, too. Of course, she was never keen on me marrying a daughter of the Third Reich, desperate as she was for me to get spliced to someone.

‘Seems like it,’ I say.

‘Oh well,’ says Mum. ‘I expect it’s for the best. You never met her people, did you?’

‘They were Nazi war criminals,’ I say. ‘I saw her Dad on Colditz the other night.’

I try and entertain myself by imagining a wedding photograph of Mum standing next to a geezer wearing jack boots, monocle, sabre scars and Iron Cross, but the ache still hangs round my stomach like suet round a kidney. I think that you only really care for a bird when she gives you the boot.

‘You wouldn’t have had anything to live on,’ says Mum. ‘There’s that to be thankful for.’

I think I know what Mum means. Sid and I are indeed skint since we parted company with Mission E and the queue at the National Assistance counter grows longer daily.

‘Yes, he’s well out of that, there’s no doubt about it,’ says Sid. ‘She doesn’t know how lucky she is, either. Still, that’s all water that’s been passed under the bridge. We’ve got to turn our minds to thoughts of the future. Talent like ours is too precious to lie mouldering on the shelf.’

‘It’s not easy to get a job these days,’ says Mum. ‘They’re laying off more people than they’re laying on them.’

‘You don’t lay on people, Mum,’ I say.

‘No, but you do,’ says Sid. Sid has what might be described as a very personal sense of humour. He is the only person to laugh at his jokes.

Mum waits for him to finish. ‘Look what happened to your father,’ she sniffs. ‘They nearly made him red - redundant.’

This is indeed true. Dad’s position at the lost property office – slumped over a desk in a posture resembling deep kip – was only preserved by the fact that a lot of people suddenly lost a lot of things and he was able to prove that London would grind to a halt without him. The situation was so desperate that he was actually taking stuff that he had nicked back to the office.

‘They should have kicked him out years ago,’ says Sid. ‘Spongers like him are the reason why this once great country of ours is in the mess it is now. The lazy old git has never done a day’s work in his life and he’s pocketing God knows how much money every week as well as all the stuff he swipes.’

‘That’s not a nice way to talk about your father-in-law,’ says Mum.

‘No, but it’s true,’ says Sid. ‘It makes me sick when I think how I’ve embodied the very spirit of Britain’s merchant greatness and ended up without a penny piece to show for it. Look at the businesses I’ve started, look at the initiative and dynamism I’ve demonstrated, look at the employment I’ve offered.’

‘Look at the wages you haven’t paid,’ I say. ‘I’m your most regular employee and I’ve hardly made a couple of quid in four years.’

‘You’re a chip off the old block and no mistake,’ says Sid. ‘Just like your old Dad. Grasping and ungrateful. You’ve had the opportunity to learn more with me than you would in a dozen business schools, but all you can think about is money. You embody everything that is wrong with this country. Frankly, I’ve had enough. I feel that Britain has betrayed me. There’s no place here any more for a man with ideals, courage and untamable ambition. I’ve thought about it long and hard in the last few days, Timmo, and I’ve decided that there is only one thing to do.’

‘Emigrate, Sid?’ I say.

‘Don’t be stupid,’ says Sid. ‘I don’t want to chuck away the National Health and the assistance – God knows, I’ve earned it. I was thinking of working out of the country for a bit.’

‘The Isle of Wight,’ says Mum. ‘That’s where I’ve always wanted to go. The climate is very like our own. I don’t like it too hot.’

‘Somewhere slightly further afield is what I had in mind,’ says Sid. ‘I was thinking of blazing the ocean’s trails in the merchant marine.’

‘Oh,’ says Mum. ‘That sounds nice. What did you have in mind exactly?’

‘A ship’s steward,’ says Sid. ‘I was talking to somebody the other night and they made it sound a wonderful job. You meet a lot of interesting people and travel all round the world. It would be like a holiday after what we’ve been through lately.’

‘What about Rosie?’ says Mum.

‘She’ll be all right,’ says Sid. ‘She’s got her business interests to look after and – you know what they say – absence makes the heart grow fonder.’

‘Like me and Gretchen,’ I say.

Sid does not savour the flavour of that remark and it is necessary for me to invest in a pint of pig’s at the Nightingale before he starts to get back to something like his normal self. ‘Wouldn’t break you to buy a packet of crisps, would it?’ he says.

‘It would as a matter of fact,’ I say. ‘What do you want?’

‘Cheese and onion,’ he says. ‘And make sure they’re not soggy.’

‘How do you reckon I do that?’ I say. ‘Grind them to powder between my fingers before I cough up the cash?’

‘I’ll leave it to you,’ he says. ‘I just can’t bear it when you can bend them.’

Two minutes later I give him a packet of Oxo flavoured crisps with the explanation that the boozer has run out of cheese and onion.

‘You know I can’t stand those,’ he says. ‘And where’s the packet of salt? They’ve started doing the salt again, you know.’

‘Maybe it’s a different make,’ I say. ‘No, wait a minute, it can’t be. I’ve got three packets in mine.’

‘Typical,’ says Sid. ‘I even miss out when it comes to the bleeding salt.’ He looks at my crisps. ‘Hey! I thought you said they’d run out of cheese and onion.’

‘They have,’ I say. ‘I got the last packet.’

‘That’s disgusting!’ says Sid. ‘Haven’t you got no manners? Your side of the family are so uncouth.’

‘You can’t talk about being uncouth,’ I say. ‘Look at all those little bits of crisp floating on top of your beer. It quite puts me off my food.’

‘Good,’ says Sid. ‘Then you won’t need your crisps.’ And he grabs my packet and shoves half of it down his cakehole.

Fortunately, that half includes two of the packets of salt as the bloke next door soon finds out when Sid spits them into an ashtray and covers his whistle in ash.

‘I don’t know what he was making so much bleeding fuss about,’ says Sid as we hurry through the door. ‘It was a grey suit. A bit of ash is good for them.’

‘Not when it covers up the pin stripe,’ I say. ‘Where are we going to go now, the Highwayman?’

‘No,’ says Sid. ‘I’m nipping up to the Palais. Do you want to come?’

‘The Palais?’ I say. ‘I haven’t been there for years. I didn’t know you were into dancing.’

‘I’m not, am I?’ says Sid. ‘I’ve got a date with this bird who might be able to help us with the steward thing. Her old man is on the turn—’ at least, that is what I think he says. It is not until I have expressed sympathy that I learn that the lady’s husband serves on a boat called the Tern.

‘What do you need me for?’ I say.

‘She’s certain to have a friend,’ says Sid. ‘They always do, don’t they? You can look after her while I sort out Gloria.’

‘She goes there a lot while her old man’s at sea, does she?’ I ask.

‘She gets lonely,’ says Sid. ‘You can understand it. Everybody needs a bit of company, don’t they?’

‘Is that where you met her?’ I ask.

‘No,’ says Sid. ‘She was in The Highwayman on Friday night. She goes up there for the charity draw.’

‘Sounds very public spirited,’ I say. ‘You giving her one, are you?’

‘You don’t ask people questions like that when they’re happily married,’ says Sid. ‘Bugger! I forgot to buy any peppermints when I was in the boozer.’

I am not over thrilled about going up the Palais because it is not cheap and I can’t dance to keep my joints from seizing up. I took a postal course once but it never showed you how to marry the footprints up to the music and you don’t like to ask your partner when to start and what sort of dance it is, do you? It is also a bit imitation posh and I don’t go a bundle on that either. You have to wear a tie in the Princess Bar and there is a Brylcreem dispenser in the gents – or ‘Caballeros’ as it is called.

‘Aren’t we going to have a few beers first?’ I say. ‘It never tastes the same with a carpet under your feet.’

‘Stop moaning,’ says Sid. ‘If we could get a job on one of these boats we could be putting ourselves in line for a new world of experiences. Gloria will be able to tell us all about it.’

‘We’d be better off with her old man, wouldn’t we?’

‘I hope not,’ says Sid. ‘Anyway, he’s chugging round the Mediterranean, lucky bastard.’ He squirts an aerosol spray round the inside of the Rover and it is clear the way his mind is working. The Alsatian in the back window will have something to nod about before the night is out.

The Palais does not seem to have changed much from when I last saw it. Maybe the manager has a little more scar tissue round his mince pies than when I last saw him but it is difficult to be certain. He looks just as suspicious and worried as he did in the old days. Sid starts to hum ‘I’m putting on my white tie’ as he fumbles for his wallet, and my stomach heaves. I have a distant recollection of Rosie’s wedding when they piled the metal chairs on top of each other in the church hall, poured sand from the fire buckets over the pools of sick and danced until the Brownies rolled up. Sid had quite a dazzling quarter turn in those days I seem to remember. And something called the fish tail that involved hopping across the floor as if it was white hot coals and somebody had dropped a jellyfish down your Y-fronts.

I am just about to suggest that Sid might like to buy me the other half when he stiffens and squares his enormous shoulders. It is obvious that somewhere amongst the crispy noodle of lacquered barnet he has spotted Gloria.

‘Right, here we go,’ he breathes. ‘Try and match my mood of breathless suavity. She likes a laugh so cheer yourself up a bit. You look like you dropped fifty pence in a dog turd.’

‘Is it true that Laurence Olivier is playing you in The Sid Noggett Story?’ I ask.

Sid does not reply because he has already fixed a horrible smile on his gnashers and is gliding forward full of wild animal magic. I follow a few paces behind him, checking on the position of the exit doors. He is steering for a couple of blondes and from behind they do not look bad. The hair colour comes straight out of a bottle but the rest of them seems natural enough. Only time and the subtle pressure of my sensitive Germans will tell.

‘Sid!’ One of the birds has turned round and her face actually lights up. This is quite something at the Palais where it is cool to treat everyone like you are only just too good mannered to tell them that they have terminal BO.

‘Hidy hi! How are we then? Looking pretty fantastic, I must say.’ Sid takes both her mitts in his and holds her at arm’s length like the two of them were left over when the screen went blank after an old Doris Day movie.

‘You’re not looking so bad yourself, is he Natalie?’

Natalie might be Gloria’s sister and she nods and giggles. Then everyone looks at me. Sid is wearing his fawn denim Sanders of the River safari suit, and both the birds have shiny dresses, so I suppose I am what you might call a bit underdressed. Certainly, Joe Bugner’s sparring partner in the dinner jacket on the door gave me an old-fashioned look. Sid swiftly gauges that the female reaction to me is not exactly white hot.

‘This is my kid brother-in-law, Timmy,’ he says. ‘He’s saving up for a suit.’

‘A paternity suit,’ I say. I reckon this is quite quick and verging on the amusing but neither of the birds seem to coco it overmuch. They are too busy running their eyes over my threads like they wish they were vacuum cleaners. I have to admit that my Chinese tank top from ‘Gone Wong’ in the High Street was a bit of a mistake and someone ought to tell the chinks that we are not all built like spaghetti with shoulder blades. Still, the Judies are clocking me from the best side because it is only when you are standing behind me that you can see where all the seams have gone.

‘Pleased to meet you,’ says Gloria without sounding as if she means it.

‘Hello,’ says Natalie with less enthusiasm than Gloria.

‘Great!’ says Sid, rubbing his hands together. ‘How would you girls fancy a drink?’

‘In a glass,’ says Gloria.

‘Oh yes, very good,’ says Sid trying to strike a few sparks off my glazed eyeballs. ‘We’ve got a couple of bright ones here, Timmo.’

‘Definitely,’ I say, trying desperately to work a little enthusiasm into my voice. ‘What would you like, girls?’

‘Pernod,’ says Gloria.

‘Pernod,’ says Natalie.

‘That’s a kind of absinthe, isn’t it?’ says Sid.

‘That’s right,’ I say. ‘You know what they say. “Absinthe makes the heart grow fonder”.’

Of course, I am wasting my time weaving dizzy verbal patterns round these birds who would probably have difficulty arranging ‘off piss’ into a well known phrase or saying, and I need my head examined trying a second attempt at humour when the first has been a disaster. If a bird starts off finding you funny, that is great, but if you are up against the strong silent type you might as well forget it. Gloria and Natalie look at me as if I have caused them physical pain and Sid winces.

‘What’s the matter with you?’ he says as he elbows me up against the bar. ‘Are you trying to make them think you’re some kind of nutter? If you can’t say anything sensible, belt up. I’d better go and set their minds at ease. I’ll have a Scotch.’ And with that, he is gone. Lea gets lumbered with the drinks again. I can see them all looking at me. Sid is saying something and the two birds are leaning forward like he is describing the first symptoms of rabies.

‘That’ll be two pounds thirty pence, mate.’

‘Two pounds thirty pence!’

‘This is the doubles bar.’

I pay up and stagger over to where Sid is sitting, determined to see a return on my investment. The last time I laid out this kind of money on a bird I thought she was buying her trousseau with it.

‘Haven’t they got any ice?’ says Gloria.

‘I’d like some water with mine,’ says Natalie.

Marvellous, isn’t it? You would think my jeans would be sodden with tears of gratitude after all the moola I have lashed out. Instead of that they treat me as if I am a blooming butler.

‘Come on, Timmo,’ says Sid. ‘Get it together. See if you can find some nuts while you’re about it.’

‘I think I know where I can find a couple straight off,’ I say.

I leave him to think about it and pad back to the bar. The plastic pumpkin is full of lukewarm water and dead flies, and when I mention ice the barman looks at me as if I have asked for the kiss of life. ‘It’s finished, mate,’ he says. ‘People take it.’

‘That’s terrible,’ I say, realising immediately that sarcasm is wasted on him. ‘Is there anywhere here I can get some?’

‘You might try the Orchestra Bar,’ he says. ‘They don’t have the same run on it down there.’

So I pour the water from the plastic pumpkin into a glass, fish out the flies, and take it back to the girls. Natalie does not even say ta but pours it straight into her Pernod.

‘Oh look,’ I say. ‘It’s turned cloudy. Do you want me to take it back?’

‘It’s supposed to do that, you twit!’ hisses Sid. ‘Piss off and find some ice.’

So I am across the dance floor like a ball of mercury and amazed to find that the plastic pumpkin on the counter of the Orchestra Bar is full of ice. I snatch it up and have taken one step back the way I came when the geezer behind the bar buries his voice in my earhole.

‘Here! Where do you think you’re going?’ he says.

‘I want some ice,’ I say.

‘Well, you can’t take that,’ he says.

‘Listen,’ I say. ‘Don’t give me a bad time. My patience is becoming exhausted. I’m not nicking your bleeding pumpkin for a kiddy’s piss pot. I just want some ice for a couple of drinks.’

‘I don’t care if you want it to embalm your pet lizard,’ says the bloke. ‘You’re not taking that tub.’

As it turns out, the bloke is right. I take another couple of purposeful strides and the ice bucket is jerked out of my hands as if it is attached to a chain fastened to the counter – which it is. A shower of iced balls fly across the floor and four couples fall arse over tit in the middle of their ladies’ excuse me. I am fortunate to be able to pick up half a dozen balls and lose myself in the confusion. When I get back to Sid and the girls, my hands are dripping and the balls have nearly disappeared – I gave them a quick suck in case they had picked up any dirt, which did not help. After all my efforts, I am not overthrilled to find that the birds have finished their drinks.

‘That’s great,’ I say. ‘I’ve got six balls and you don’t want any of them.’

‘Stop lying and being disgusting,’ says Sid. ‘You must learn to judge when you’re giving offence.’ He turns to Gloria. ‘Would you care to take the floor?’

‘Watch him,’ I say. ‘He won’t even help you carry it out to the lorry.’

I know what I said a few paragraphs ago but sometimes you don’t care, do you? Sid goes past me with a look of disdain illuminating his noble features and soon he and Gloria are dancing their way into the record books. That leaves me with Natalie and my bus fare home. It is for this latter reason that I ignore her blood red fingernails toying with the stem of her empty glass.