English History: People, places and events that built a country

Though he is not much talked about today, some historians say Athelstan should be remembered as the first King of England. When Athelstan became king, Northumbria remained an outpost of Viking power centred around the Viking capital of Jorvik. Athelstan gradually asserted Anglo-Saxon power over Northumbria, and in 937 he won a great victory at the Battle of Brunanburh, against an enormous Scottish, Viking and Northumbrian army. During his reign, Athelstan had new coins minted for his kingdom, on which he gave himself the title Rex Anglorum, meaning ‘King of the English’. For the first time since the Roman conquest, England could be described as a unified country under the rule of a single leader.

1042 | Edward the Confessor

In 1042, the English throne returned to Anglo-Saxon rule under Edward the Confessor. Edward the Confessor was mild-mannered, middle-aged, and extremely religious – hence his title ‘Confessor’. This intense religious faith may explain why King Edward remained childless even after he married. Edward’s failure to provide an heir set the scene for perhaps the most famous event in English history.

As Edward the Confessor drifted into old age, three claimants started jockeying for the right to succeed him as King of England. Firstly, there was Harold Godwinson, the Earl of Wessex. Harold was a powerful Anglo-Saxon nobleman, and brother-in-law to the king through his sister Edith. Second, there was William Duke of Normandy, a ruthless warrior from France who claimed to have been promised the throne by King Edward back in 1051. Lastly, there was the King of Norway Harald Hardrada, who wanted to return England to Viking rule.

Edward the Confessor did leave England another historic legacy, aside from an uncertain throne. His life’s work was the construction of Westminster Abbey, consecrated in December 1065, one week before Edward’s death. When completed, Westminster Abbey was the largest church in northern Europe, and has witnessed the coronation of every English monarch since 1066.

1066 | King Harold

Edward the Confessor died on 5th January 1066. As he lay dying, Edward bequeathed his throne to Harold Godwinson, the Earl of Wessex. On 6th January, Harold was crowned King at Westminster Abbey. He was to be England’s last Anglo-Saxon king.

The Godwin family were known for their ruthless ambition, but lacked royal blood. Many feared that seizing the English throne had been a step too far. These fears appeared to be confirmed in April 1066 when a burning comet appeared in the night’s sky. Was this a bad omen, showing God’s anger that an illegitimate king now sat on the English throne?

In September 1066, a Viking invasion force led by Harold Hardrada sailed up the Humber River and took York. Hardrada was accompanied by Harold Godwinson’s treacherous younger brother, Tostig. Harold marched his Anglo-Saxon army north to meet the Vikings, and caught them by surprise on the morning of 25th September at a location named Stamford Bridge. The Anglo-Saxons won a great victory, annihilating the Viking force and killing both Tostig and Hardrada. But this victorious start to Harold’s reign did not last long.

Richard Pinder / shutterstock.com

1066 | Battle of Hastings

No sooner had King Harold vanquished the Viking invaders, he received news that the Duke of Normandy’s invasion force had landed on the south-east coast of England. Harold demanded that his army march the length of England in little over two weeks, and on 14th October they met the Norman invasion force 10 miles inland from the town of Hastings. This battle would decide the course of English history.

Harold’s army of 7–8000 men men were weak and outnumbered by William’s superior army, which included heavily armoured knights on horseback and archers. In all, the Normans numbered perhaps 10,000 men. Despite this, the Anglo-Saxons started well, creating a defensive shield wall on top of the high ground of Senlac Hill. However, repeated waves of Norman attack slowly broke the Saxon formation.

What happened next is hotly disputed. According to one story, Harold Godwinson was shot through the eye by an arrow, and then dismembered by Norman knights. This is what appears to be shown in the famous Bayeux Tapestry, a magnificent 70 metre-long embroidered cloth that was created to celebrate the Norman invasion (see picture). After six hours of brutal fighting, William Duke of Normandy was victorious.

Ancient Art and Architecture

1060S and 70S | Norman Conquest

On Christmas Day 1066, the Duke of Normandy was crowned King William I of England at Westminster Abbey. In the years that followed, William was brutally effective at spreading Norman power throughout his new kingdom. The Normans would respond to any Anglo-Saxon rebellion by descending on their community, burning down their villages and slaughtering their inhabitants.

Perhaps the most infamous occurrence of Norman cruelty took place in 1069, when William’s newly appointed Earl of Northumbria was murdered by Anglo-Saxon rebels. William was furious, and vowed to make an example of the Northern rebels. His army marched north, and burnt to the ground every village between York and Durham. Farm animals were slaughtered, crops were destroyed, and the fields were laced with salt so that no more food could be grown. Known as the ‘Harrying of the North’, this event led to the starvation of perhaps 100,000 people.

Other examples of Anglo-Saxon rebellions and resistance took place, but all in vain. Through sheer military superiority, William’s occupying force of 20,000 men were able to subdue a population of two million. England’s era of Anglo-Saxon rule was firmly at an end.

Daniel_Kay

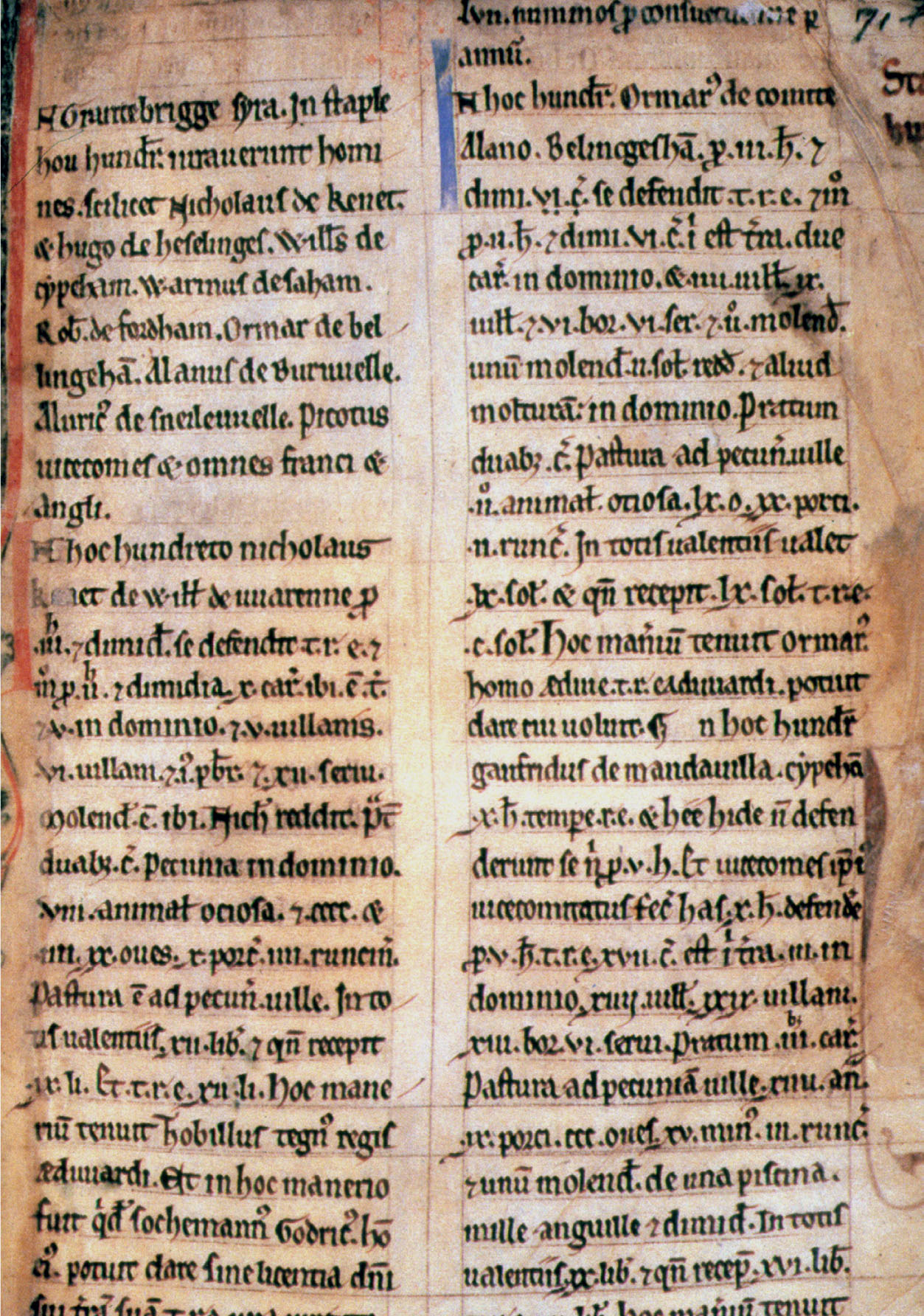

1086 | Domesday Book

Having conquered England, William set about creating a new ruling class of Norman noblemen. William seized the land from England’s Anglo-Saxon noblemen, many of whom had died fighting at Hastings, and transferred its ownership to his loyal Norman knights. Norman noblemen were given titles as Earls and Barons, and in the centre of their land they built large, intimidating castles to confirm their power. A strict social hierarchy (sometimes called the feudal system) was created, with Norman noblemen at the top, and their Anglo-Saxon vassals below.

To keep a record of this enormous transfer in land ownership, William the Conqueror ordered the Domesday Book to be written. For two years, Norman commissioners travelled the length and breadth of England, recording what this new kingdom contained down to the last pig, plough and beehive. Completed in 1086, it details the contents of over 13,000 different towns and villages. It is one of England’s most valuable historical documents, providing an extraordinary picture of life in the 11th century. For example, in 1085 Birmingham was a small village with just nine families and two ploughs. Today, it is England’s second largest city.

Granger Historical Picture Archive

1170 | Murder of Thomas Becket

Henry II was an energetic king, who rebuilt the power of the English monarchy after nineteen years of bloody civil war. But he is chiefly remembered for English history’s most famous murder. As king, Henry II wanted to gain more power over the English Church, so in 1161 he made his loyal friend Thomas Becket the Archbishop of Canterbury (leader of the English Church). However, on becoming archbishop, Becket transformed into a pious defender of Church independence.

Becket refused to take orders from Henry II, and their friendship transformed into bitter hatred. During a particularly foul dispute in 1170, Henry II allegedly screamed ‘will nobody rid me of this turbulent priest!’ Four knights interpreted Henry II’s outburst as an order, and rode to Canterbury Cathedral. They killed the Archbishop with a blow to the head by a sword, and smeared his brains across the Cathedral floor.

Henry II insisted that the murder of Thomas Becket was a tragic mistake, and did penance by walking barefoot to Canterbury where he was whipped by the Cathedral monks. Becket meanwhile was celebrated as a martyr for defending Church freedom, and made a Saint. His shrine became one of the most popular pilgrimage sites in medieval Europe.

Zvonimir Atletic / shutterstock.com

1204 | Eleanor of Aquitaine

Henry II’s wife, Eleanor of Aquitaine, was a remarkable Queen. In 1137, aged only fifteen, she married the King of France, Louis VII. However, Louis could not tolerate Eleanor’s independent mindedness, and they divorced in 1152. Eight weeks later, Eleanor shocked medieval Europe by marrying the heir to the English throne, the future Henry II. Henry II and Eleanor’s marriage started well having seven children together, but they began to quarrel. In 1174, Eleanor was arrested for plotting against her husband, and thrown in prison for sixteen years. When Henry II died, Eleanor’s favourite son Richard the Lionheart became King of England, and freed his mother from imprisonment.

Richard the Lionheart, whose statue stands outside the Houses of Parliament, is one of England’s most famous kings. However, he spent as little as six months actually in England during his ten-year reign. For most of the time, he was fighting on crusade in the Holy Land. Whilst Richard was fighting foreign wars, it was his mother, Eleanor of Aquitaine, who ruled England. She died in 1204 at the astonishing age of 82, having become one of the most powerful and respected figures, male or female, in all of Europe.

mountainpix

1215 | King John and the Magna Carta

No medieval King of England has as bad a reputation as King John. John was Henry II’s youngest son, and became king in 1199 after the death of his older brother Richard the Lionheart. Many believed John’s nephew Arthur had a better claim to the throne. Before long, rumours began to circulate that to secure his hold on power, John had drowned his own nephew in the River Seine.

John was ruthless in punishing those who opposed his rule, often starving his enemies to death in castle dungeons. He repeatedly argued with the Catholic Church, and was excommunicated by the Pope. Worst of all, John was a hopeless warrior, and lost much of England’s territory in France, including his ancestral homeland in Normandy. To fight these unsuccessful wars, John taxed his Barons dry. But John’s tyrannical rule did leave a positive legacy. In 1215, the Barons united against King John, and forced him to sign a series of promises known as the Magna Carta. These promises included the right to a fair trial, independence of the church, and the need to gain the Barons’ consent before raising taxes. Today, the Magna Carta is seen as the birth of political rights in England.

The image opposite shows a memorial in Runnymede, the meadow beside the River Thames where King John agreed to the Magna Carta.

Paul Daniels

1200S | Robin Hood

Did Robin Hood even exist? Probably not. However, the legend of Robin Hood was popular in England from the 15th century onwards, and tells us a lot about medieval attitudes towards tyrannical royal power. Robin Hood is the outlaw of Sherwood Forest, who steals from the rich to give to the poor. A skilled archer, Robin terrorises the Sheriff of Nottingham and his master, Prince John, who has taken the throne from his brother Richard the Lionheart. Robin Hood is helped by his band of ‘merry men’, including Little John (who is actually very tall), Much the Millar’s son, and the rather less-than-pious Friar Tuck.

In later years, Robin Hood was depicted as a deposed Saxon nobleman, fighting back against oppressive Norman overlords. Woodlands such as Sherwood Forest were kept as royal hunting grounds by the royal kings, and those caught poaching on these grounds were cruelly punished. Today, you can visit the ‘Major Oak’, a hollow oak tree in Sherwood Forest where, according to legend, Robin and his merry men once hid. Sadly, Major Oak was not even an acorn during the reign of King John.

WDG Photo

1265 | The first Parliament

King John’s son Henry III was forced to reaffirm the Magna Carta (see here) in 1225, setting a precedent for all future English monarchs. Henry III had great military ambitions, wanting to reconquer the land lost by his father in France, go on a crusade to the Holy Land, and even make his son the king of Sicily. However, all of these foreign wars meant increases in taxation.

In 1264, a group of rebel barons led by the Earl of Leicester Simon de Montfort rose up against Henry III. At the Battle of Lewes, de Montfort defeated Henry III and took him prisoner. De Montfort then summoned all England’s bishops and noblemen to London, along with representatives from every shire and borough in the land. On 20th January 1265 they met at Westminster Hall as a ‘Parliament’, taken from the French verb parler (‘to speak’).

De Montfort’s Parliament is often called the first English Parliament. It gave institutional form to the promise in the Magna Carta that the monarch’s government should seek the consent of its people before passing new laws and taxes. Parliament still represents this principle today.

1283 | The Conquest of Wales

Since 1066, the Norman monarchs repeatedly tried to conquer Wales, but with little success. By the 1260s, most of Wales was under the control of Llywelyn ap Gruffyd. As the Prince of Wales, Llywelyn was expected to pay homage to the English king, but when the young Edward I was crowned king of England in 1174, Llywelyn refused to do so. Edward I was a brutal and warlike king, and saw this provocation as an opportunity to bring England’s troublesome neighbour under his control. In 1277, Edward invaded Wales with an enormous army. Five years later, Llywelyn was killed in battle, and his head was taken back to England to be displayed on a spike at the Tower of London. Llwyelyn’s brother, Dafydd, carried on the fight until 1283, when Edward captured Davydd and had him hung, drawn and quartered.

Having conquered Wales, Edward set about building a series of enormous castles to secure his power. For this reason, Wales has the highest concentration of castles of any country in Europe. Edward did not get rid of the title ‘Prince of Wales’, but gave it to his eldest son, thus beginning the practice of giving this title to the heir to the English throne.

1337 | The Hundred Years War

Ever since the Duke of Normandy conquered England in 1066, English monarchs had held territories in France. This led to ongoing tension between the French and English Kings, which frequently spilled over into war. In 1328, King Charles IV of France died without a male heir, and his throne passed to the French Count of Valois, who became Philip VI of France. However, the English King Edward III, whose mother was a French princess, believed he had a stronger claim to the throne. In 1337, Edward III declared himself the rightful King of France, marking the start of the Hundred Years War.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.

Вы ознакомились с фрагментом книги.

Для бесплатного чтения открыта только часть текста.

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера:

Всего 10 форматов