Air Force Blue: The RAF in World War Two – Spearhead of Victory

Copyright

William Collins

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.WilliamCollinsBooks.com

This eBook first published in Great Britain by William Collins in 2017

Copyright © Patrick Bishop 2017

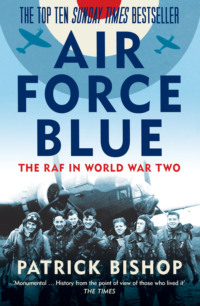

Cover image: RAF bomber pilots return home from a successful mission (Photo © Hulton-Deutsch Collection/CORBIS/Corbis via Getty Images)

Maps by John Gilkes

Patrick Bishop asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780007433155

Ebook Edition © September 2017 ISBN: 9780007433162

Version: 2018-05-29

Dedication

TO HEN

ANGEL GIRL IN CHIEF

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Maps

Prologue: Firstway

1 The Big One

2 A Cottage or a Castle?

3 Smoke and Mirrors

4 Brylcreem Boys

5 ‘There’s Something in the Air’

6 ‘Tragic, Criminally Tragic’

7 The Battle

8 Fighting the Night

9 Ten Million Miles of Sea

10 The Blue

11 ‘Eat, Drink and Be Merry …’

12 ‘Britain’s Best Advertisement’

13 Out of Sight

14 Black and White

15 The Hyacinths of Spring

Epilogue: Brothers and Sisters

Acknowledgements

Notes

Picture Section

Index

Also by Patrick Bishop

About the Author

About the Publisher

Maps

Fighter Command’s area of operations 1940

Main Bomber Command stations in the UK

Main targets in Europe

The Mediterranean, Levant and Southern Europe, showing the Takoradi Route

North-East India and Burma

Normandy and North-West Europe

Prologue

Firstway

In the spring of 1944 the chief information officer with the Royal Air Force permanent delegation in Washington, DC, reported back to London on how the service was regarded on the other side of the Atlantic. ‘We cannot hope to enhance the prestige of the RAF,’ he wrote. ‘Throughout the world it is a household word, and in the United States its reputation is so high that in some quarters it is almost regarded as something apart from, and superior to, Britain.’1

The Americans were not easily impressed. Since joining the war they had become the dominant partners in the alliance and the attitude of US commanders towards the British Army and Navy could be tinged with a condescension that was sometimes amused and often exasperated.

The information officer’s report, smug though it sounded, was essentially accurate. The RAF was seen differently. Unlike the other services, it attracted quasi-automatic admiration and respect. American airmen regarded their British comrades as something like equals; energetic, efficient and providing an operational contribution that added real weight to the Allied war effort.

In March 1944 when the report was written, Britain and the US had settled on the command structure for the forthcoming great invasion of northern Europe, and Dwight D. Eisenhower was chosen as Supreme Allied Commander. Eisenhower knew who he wanted as his second-in-command: Arthur Tedder of the RAF, who he had got to know intimately during the Mediterranean and Italian campaigns. ‘Ike’ had been Tedder’s best man when he married for the second time. Tedder was Eisenhower’s ‘warm personal friend’2 and the man he most admired and trusted among the British high command.

The US military’s assessment of the quality and worth of their allies was based initially on observation, then on direct experience. For the first ten months of the war the Army’s record was one of debacle and defeat in Norway and France ending in the ignominy of Dunkirk. In North Africa, it floundered against a weaker enemy, and a golden chance for a quick ending was squandered when Churchill decided to switch forces to Greece in a hopeless attempt to stem the Nazi invasion. The eventual victory at El Alamein was the result of a marked numerical superiority in men, guns, tanks and aircraft. It was the first and last time that a British and Commonwealth force would beat the Germans on their own. Thereafter almost all of the Army’s effort in the West would be in conjunction with, and ultimately subordinate to, the Americans.

At sea, the war disobligingly failed to develop along the lines that the Admiralty had planned for. There would be no major fleet showdown between the Royal Navy and the Kriegsmarine and the huge and expensive battleships the admirals set such store by absorbed commensurate resources and manpower, which had to be diverted from more productive activities in order to protect them. The Navy did, of course, secure at great cost and effort the sea lanes that kept Britain in the war, but the Battle of the Atlantic was a struggle for survival rather than an advance towards victory. Fighting it took all their time and British warships did not contribute anything to the US Navy’s campaign in the Pacific until January 1945.

The information officer’s belief that the Air Force was perceived as something ‘apart from’ and ‘superior to’ Britain was telling. The Americans did not do sentimentality. The notion that cultural and historical connections meant that Britain was owed deference had long ago vanished. Some in the British military and political establishment did not seem to have noticed that things had changed. Transatlantic visitors were used to being talked down to by their hosts, who drew on centuries of imperial wisdom to instruct and correct. Americans believed they had little to learn from a nation that was fast losing its world-power status and in the space of a generation had twice been forced to turn to them for salvation.

Their dealings with the RAF brought a pleasant surprise. In the early autumn of 1940, when America was still more than a year away from entering the war but already supplying Britain with materiel, a delegation toured Egypt. Colonel Harvey S. Burwell of the US Army Air Forces (USAAF) was greatly impressed by the spirit of the pilots and ground crews, praising their ‘superb morale, extraordinary patience and wonderful courage’.3 He met Tedder, then head of the RAF’s Middle East Command, and some of his senior officers and was relieved to find that ‘the [British] supercilious superiority so objectionable to Americans is rarely exhibited’. The impression persisted so that the information officer was able to state in his 1944 report from Washington that ‘many people who dislike the British would not say a word against the RAF’.4

This image of unstuffiness was reinforced by a well-orchestrated stateside propaganda effort, promoting the RAF’s achievements and personalities. Guy Gibson, hero of the May 1943 Dams Raid, was pressed into service as an ambassador. In September that year he swept across North America charming interviewers, reporters and radio audiences and receiving the sort of reception normally accorded to movie stars. Humility was not a quality readily associated with Gibson at home. Abroad, however, he was seen as a ‘thoroughly nice, modest young man with a good sense of humour’.5

Above all, he was unmistakeably a great warrior. The Dams Raid was an epic feat of arms. It immediately attracted the attention of the Hollywood director Howard Hawks, who invited Gibson to stay with him in Los Angeles. Hawks commissioned a script from Flight Lieutenant Roald Dahl, a former fighter pilot then serving as a press attaché in Washington (though this version foundered on the objections of Barnes Wallis, the scientific brains behind the operation).

The Air Force projected confidence, aggression and efficiency. Whatever the Americans thought about Britain’s contribution on land and sea, no one could deny that in the air it more than pulled its weight. The first American bombs fell on Europe in August 1942. In the twenty-nine months that followed, the USAAF never matched the tonnages showered down by the RAF. It was only in January 1945 that they began to pull ahead. The final balance showed that, in the bombing war in Europe, Bomber Command dropped 873,348 tons of ordnance and the United States Eighth Air Force 621,438.6 In this field of the great Allied endeavour in the West, the British were seen to deliver more and suffer more than the US in both men and machines.7

At the business of strategic bombing, British aircraft were the best in the world. The Avro Lancaster and Handley Page Halifax were the same size as their American counterparts, the Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress and Consolidated B-24 Liberator. However, they carried much heavier bomb loads; 10,000lb against the Fortress’s 5,000lb.8

So when Americans looked at the RAF they saw an organization that did not conform to their notions of Britishness but something more akin to themselves, matching them for ambition, efficiency and swagger. Military forces mirror the values of the society they spring from. The image of Britain that the RAF presented in the glass was not the same as that reflected by the Army and the Navy. The old services represented the past. The airmen were the incarnation of how new Britons viewed themselves: modern, competent, democratic and reluctant to give to those above them the automatic deference that had hitherto been expected.

This picture of the RAF was widely accepted both inside and outside its ranks. As a result of the great attention paid to it by the press, the radio and the newsreels, the Air Force came to be seen as a repository of a new set of national values. It was a development that suited the government’s information strategy and it was soon endorsed as a recurrent trope of British propaganda. The approach carried hidden risks. In it was contained an implicit promise that the ethos the RAF enshrined would be given political expression and influence the future shape and direction of the country once the war was won.

As the conflict approached, the people of Britain absorbed the idea that the Air Force would play the dominant role in the coming struggle, as the guarantors of their survival and the agents of eventual victory. On 1 October 1938, the first issue of the weekly news magazine Picture Post appeared. It was lively, outspoken, thoroughly modern in outlook and almost immediately won a big circulation and considerable political influence. The second issue carried a long article entitled simply ‘The RAF’, part of a series intended to shed light on ‘our great national institutions’.9 It was written by Nigel Tangye, a young journalist-about-town who was also a pilot and officer in the RAF reserve. Tangye had good connections with the Air Ministry and it would have been surprising if he had not checked with them before making the momentous claim that ‘the RAF holds today a position of importance higher than the Army or Royal Navy’. The duties of the Air Force of protecting the national territory, preserving vital sea trade routes, defending the empire and lending aid to allies amounted to ‘everything which for hundreds of years has been the function of the Royal Navy’.

Publicity frequently stressed its ‘democratic’ nature, compared to the other services. ‘Officers and men in the Royal Air Force share a common spirit which is unknown either in the Army or the Navy,’ wrote Tangye. ‘So much of the Navy’s time is spent in scrubbing decks, so much of the Army’s in massed drilling. But the Air Force Machines have to fly every day, and the crews of each are bent on keeping them in tip-top condition.’

It was never presented as a classless organization. That would have been too much to claim in a society which, though lines were blurring, was still strictly defined by birth, money, education, accent and manners. It did, however, seem something like a meritocracy in which the near-revolutionary notion that competence was more important than background had taken hold.

The Air Force needed a large cadre of expert tradesmen to keep it flying. They came, largely, from the lower-middle and upper-working classes, and the educational gap between other ranks and officers was consequently narrower than in the Army and Navy. The need for aircrew opened the door to the officers’ mess to young men who would never have passed muster in the 1920s and 1930s.

The literary types sent in the early years of the war by the Air Ministry on fact-finding tours of bases to gather propaganda material were struck by the varied origins of the officers they encountered. The Oxford don Lord David Cecil noted after a visit to a bomber station in 1941 how ‘compared with the Army or Navy the men of the RAF seem very diverse … very varied … drawing its members from every sort of rank and profession’.10 Sitting down to dinner in the mess he found on one side of him ‘a boy fresh from a public school; on the other side a bank clerk; opposite, a New Zealander, next to him a garage worker, next to him a law student’.

The service was too young, he concluded, to have ‘evolved a traditional type’ to which all must conform: ‘Their upper lips are not too stiff. On the whole their manners tend to be expansive. There is often a touch of jaunty flamboyance in the way they walk and speak and wear their uniforms, with an elegant identification bracelet glinting on the wrist.’

Air Force style was in bright contrast to the dowdiness of the other services. As a boy watching the build-up to D-Day around his home in the West Country the military historian John Keegan was disappointed that the British soldiers he saw ‘wore khaki from top to toe … so ill-cut, shapeless and hairy that I could find almost nothing in its wearers to admire’.11 When the Americans arrived he and his school friends were amazed at ‘how different they looked from our own jumble-sale champions, beautifully clothed in smooth khaki …’ They were even more impressed by the ‘number, size and elegance of the vehicles in which they paraded about the countryside in stately convoy’, so unlike the ‘sad collection of underpowered makeshifts, whose dun paint flaked from their tin pot bodywork’ that the Army had to make do with.

No one had to feel sorry for the RAF. The aircrew could equal their Yank counterparts in swank and dash and even the earthbound ‘erk’ had the edge over his ‘brown job’ and matelot comrades. Their uniform may have been of serge but they wore a collar and tie to go to work and their hair, curling from under their distinctive two-button side caps at a length that would have given a sergeant-major apoplexy, was as like as not gleaming with Brylcreem.

It was no longer the case that all the nice girls loved a sailor. In October 1939 ‘Just An Airman’ wrote to Picture Post complaining that after joining the Air Force his girlfriend had dumped him and since then he had found that ‘no decent girl seems to look at an airman’. He went on: ‘I am five feet 10 inches tall, good at sports and reasonably good looking. Once I had girlfriends. Now the only place I seem welcome is at the public house.’12

His self-pitying and possibly self-serving missive produced an avalanche of positive responses, a selection of which was printed over a double-page spread. ‘I, as a young lady of nineteen, was very surprised to read your correspondent’s letter,’ wrote Joyce Dickinson of London Road, Rainham, Gillingham, Kent.13 ‘Many young ladies, including myself, admire members of the Royal Air Force and feel especially proud when we read of their daring and brave exploits on the Western Front and over Germany. He may rest assured that although one girl has turned him down, many of us would like the opportunity to make his acquaintance.’

From Wallasey in Cheshire ‘An Admirer’ declared: ‘I think many readers will agree with me when I say that the RAF is the finest of the three services. I am not saying anything against the Navy or the Army … but I prefer the Air Force.’

It was little wonder that when conscription began more men exercised their right of choice in favour of the Air Force over the other services. The RAF seemed immune to the criticism that the Army in particular sometimes attracted. The war in the air got off to just as bad a start as it did on land and sea. Bomber Command’s early record was one of continuous failure and heavy, pointless losses, and the pattern was maintained by all branches of the service in the campaigns in Norway and France. Government propaganda and a co-operative media skated over this truth.

Then, in the summer of 1940, in full view of the population, Fighter Command won the Battle of Britain, supercharging national morale and gilding the Air Force with an aura of success that never tarnished. ‘The RAF are the darlings of the nation!’ wrote John Thornley, a twenty-nine-year-old salesman from Preston, Lancashire, in his diary in July 1940.14 ‘What magnificent chaps the RAF pilots must be,’ he declared a month later as the Battle approached its climax.

By the end of the summer its reputation seemed unassailable. Britain’s city-dwellers proved remarkably willing to overlook Fighter Command’s inability to protect them from the nightly Blitzes that devastated their homes in the winter of 1940–41, preferring to blame politicians for the lack of counter-measures. Major flaws in the Air Staff’s thinking and preparations such as its blind faith in strategic bombing and the initial failures to co-operate effectively with the Army and Navy were never really exposed to public view. The RAF’s numerous critics in the upper echelons of the other services complained that it appeared subject to different rules from the ones they had to obey. Often it seemed a law unto itself, holding, in the opinion of the soldier-historian Bernard Fergusson, ‘an unwritten charter direct from the war Cabinet’ that allowed it to direct bombing policy and decide on what types of aircraft were needed without having to consult with soldier and sailor colleagues.15

In two previous books, Fighter Boys (2003) and Bomber Boys (2008) I told the story of the RAF in the Battle of Britain and the Strategic Offensive against Germany, conveying events, emotions and attitudes as much as possible from the perspectives of the participants. In this final work in the trilogy, I hope to extend the field of vision to the whole of the Second World War. A comprehensive history is impossible in one volume. There was too much being done by too many people. Instead I have tried to examine essential aspects of the RAF wartime experience, both for those flying and those on the ground in selected battles and theatres, in the process, I hope, colouring in the RAF’s distinct identity. So this is not a chronicle of the war in the air. It is about the spirit of the Air Force, its heart and soul.

Again, I have tried to see things through the eyes of the players, relying wherever possible on contemporary documents, diaries and letters and, where they are not available, memoirs and reminiscences. I was lucky enough to meet and interview many veterans during my earlier research and could draw on their memories of other parts of their service not covered in previous books. There is, I was pleased to discover, still much rich material lying undiscovered in the archives which provides new evidence and insights.

This book is about many things but a recurrent theme is the special relationship that the Air Force enjoyed with the nation at this uniquely testing time in its history. For much of the war the RAF was Britain and Britain was the RAF. The conflict arrived in the middle of a time of great transformation, when British characteristics and attitudes were undergoing profound changes.

Davis Estates advert, 1930s (Pictorial Press Ltd/Alamy Stock Photo)

Among the girls who responded to ‘Just An Airman’ was Joyce Robinson of Firstway, Raynes Park, London SW20. She, too, was an Air Force fan, admiring ‘the spirit of adventure which prompts a man to join’.16 The street is half a mile from where I grew up. It was built in the 1920s by an energetic master builder called George Blay who turned much of what was then countryside into suburbia. It is a tree-lined cul-de-sac of nice, three-bedroomed terraced houses, with bay windows, timberwork on the façades and ample back gardens. They cost £675 (with 85 per cent mortgages available) and were a few minutes’ walk from Raynes Park station on the Southern Electric railway which ran straight in to Waterloo. Thousands of streets like Firstway were springing up around Britain’s cities at the same time.

The families who lived in them were members of the most overlooked and underappreciated stratum of the social layer cake – the lower-middle class. The cautious patriarchs of these ‘quadrants’, ‘crescents’, ‘drives’ and ‘walks’ left each morning for their jobs as clerks, draughtsmen, shopkeepers and minor civil servants while Mum stayed home to clean and cook. Their children raised their eyes to broader horizons. I have not managed to discover anything about Joyce Robinson but I have imagined her: playing tennis at the club round the corner in Taunton Avenue, watching Clark Gable in Gone With the Wind at the Raynes Park Rialto, taking the District Line to Hammersmith to dance at the Palais, perhaps driving with a boyfriend to a roadhouse on the Kingston by-pass.