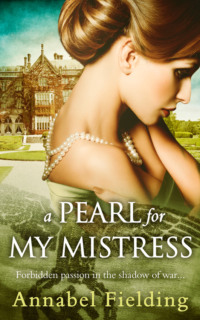

A Pearl for My Mistress

England, 1934. Hester Blake, an ambitious girl from an industrial Northern town, finds a job as a lady’s maid in a small aristocratic household.

Despite their impressive title and glorious past, the Fitzmartins are crumbling under the pressures of the new century. And in the cold isolation of these new surroundings, Hester ends up hopelessly besotted with her young mistress, Lady Lucy.

Accompanying Lucy on her London Season, Hester is plunged into a heady and decadent world. But hushed whispers of another war swirl beneath the capital… and soon, Hester finds herself the keeper of some of society’s most dangerous secrets…

A Pearl for My Mistress

Annabel Fielding

ONE PLACE. MANY STORIES

Contents

Cover

Blurb

Title Page

Author Bio

Dedication

Prologue

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-One

Chapter Twenty-Two

Chapter Twenty-Three

Historical Note

Endpages

Copyright

ANNABEL FIELDING,

having graduated from the University of Arts London with an MA in Public Relations, is a PR assistant by day and a novelist by night. Being a self-professed history geek, she dedicates her free time to obscure biographies, solo travel and tea. She also posts a mix of book reviews and travel photos on her blog at http://historygeekintown.com

To my dearest Eugenia, who readily shared my rage and my love for so many things.

Prologue

London, May 1933

Afternoon sunlight streamed through the majestic windows of the Claridge’s hotel. It danced across the room, reflecting on the new glass panels, throwing patches of light on Eleanor’s red hair. It illuminated the black-and-white mosaic, the cream-coloured pillars, and the gold-coloured walls. The whole restaurant now seemed to be serenely floating among the radiant clouds, all its patrons transformed into ethereal beings.

‘So, tell me about this new novel of yours.’

Only the sense of decorum must have prevented Eleanor from leaning across the table.

Her name always seemed a little too ceremonious for her, too decorous, too grand; perhaps, that is why she was usually fondly referred to as Nora.

‘Well, I wouldn’t go so far as to call it a novel already.’ Charity shook her head. ‘It’s still more of an idea. It may come to nothing in the end.’

‘Do tell!’

‘You see, I’ve grown a little tired of English country houses …’

‘Who wouldn’t?’ Eleanor shrugged. ‘They are dreadful. I still don’t know how I managed to survive my childhood winters there.’

The corner of Lucy’s mouth twitched. She understood this sentiment better than most. Last year, she couldn’t have been more relieved that her family had finally capitulated and decided to install central heating in Hebden Hall. Perhaps capitulation was too strong a word; actually, it was more of a compromise. If the house absolutely had to be defiled by this new apparatus, they thought, then the change must, at least, remain unobtrusive. Therefore, the radiators were concealed by complicated latticework and tucked as far from prying eyes as possible.

Lucy didn’t mind. At least now she wouldn’t have to dress in a way that called to mind early Antarctic explorers.

‘I mean, I am tired of writing about them,’ Charity said, her eyes laughing.

‘Again, who wouldn’t be?’ Nora sighed deeply and shook her head, making the lush red tresses sweep across her shoulders.

The Honourable Miss Eleanor Palmer was nothing if not expressive. Few people would have called her beautiful; however, she definitely possessed a certain presence. Indeed, most ordinary mortals seemed to grow somehow muted while in her radius. Even Charity Williams, a self-assured Oxford graduate and an acclaimed novelist, looked quite subdued next to the heiress. A small, pale debutante like Lucy was simply destined to blend in to the surroundings.

‘So, where will this new novel be set?’ Nora asked, as she finished the delicate cucumber sandwich.

‘I’m planning to write about Venice.’

‘Venice? But how marvellous!’ Nora all but clapped her hands. ‘I’ve spent so many delightful months there. Speaking of which, have you ever been to Venice?’

‘That’s the difficulty, I’m afraid.’ Charity smiled wryly. ‘I haven’t. I know Mrs Radcliffe used to set her Gothic novels in Italy while knowing it only from dramatic paintings, but I don’t think anyone can get away with that sort of thing now.’

And even if they could, Lucy thought, Charity would never do such a thing. She has always been thorough. Lucy admired that.

Miss Williams’ world seemed to her as improbable and fantastic as the legends discussed in Charity’s beloved Oxford by her equally beloved Professor Tolkien. In this world, there were heated intellectual discussions and fondly remembered debates. There were books, written by Charity herself, finished and published and acclaimed. There were no chaperones.

Lucy strained her ears to hear Charity better every time they happened to meet in the same company.

Lucy’s father, the esteemed pillar of local gentry, was of the opinion that schools only spoiled girls, and excessive reading was unwholesome for any child. Following that logic, universities should have probably spoiled them to a frightening degree. Charity showed no sign of being affected by such corruption, though.

How strange this reserved intellectual looked at Eleanor’s side. The latter always conducted herself as if she were playing an American heiress in a bad musical.

In a twist of irony, Nora’s late mother, a real American heiress, was reputed in her day to be the demurest creature on the whole London scene. This must have been why the shy foreigner drew Sir Frederick Palmer’s attention back then – aside from her money, of course. After all, the young baronet was already used to the high life, and Marianne Lindley’s dowry freed him from the daunting prospect of parting with his habits.

‘Well, this shouldn’t be a problem!’ Nora exclaimed, making the couple at the nearest table turn in her direction. ‘Our holiday home in Lido stands empty for most of the year. It isn’t in Venice proper, of course, but it’s close enough. Twenty minutes by boat, I think. Perhaps, thirty, if you are unlucky. No one is going to be using it for several months. Although, if I were you, I’d wait until autumn,’ she added. ‘Italy in summer feels like a local branch of hell.’

‘You are going to give me the keys to your holiday home?’ Charity asked with disbelief ringing in her voice. Lucy shared her perplexity.

‘Why not?’ Nora shrugged. ‘As I’ve said, no one is going to live there for some time. Father and Lady Isabelle are planning to spend this autumn in France.’

Eleanor almost never spoke of anyone with open bitterness. However, Sir Frederick Palmer’s second wife was never a ‘mother’ or even a ‘stepmother’ – always ‘Lady Isabelle’.

‘If you are sure that it will cause you no trouble …’ Charity still sounded doubtful.

‘Absolutely not!’ Nora reached across the table to squeeze her hand. Charity flinched almost imperceptibly. Lucy could understand that – Nora was charming, but her propensity for touching people like that always came across as a little startling.

‘You are an angel. I only hope the new government won’t take offence at my visit.’

‘Oh, that’s probably the last thing you should worry about.’

‘Well, people are telling all sorts of stories.’

‘Believe me: I go to Venice every year, and I haven’t noticed anything sinister so far.’

‘It’s not just Venice,’ Charity remarked. ‘The Continent as a whole is going a little wild lately. Have you heard of what happened in Germany?’

‘You mean the appointment of this new Reich Chancellor? Oh, of course. I’m afraid I missed the first flurry of gossip, though,’ Eleanor confessed. ‘I’ve spent almost the whole winter on that safari, and it’s not easy to keep track of Kenyan rhinoceroses and European politics at the same time. But everyone enlightened me once I came back. Some people thought it to be a great joke, and, to be honest, I agree. Wasn’t he a common soldier?’

‘I’ve heard he was a painter.’

‘Even better!’

‘I thought you’d always supported the arts,’ Charity teased.

‘But not quite to that extent!’ Nora rolled her eyes. ‘We have our own fair share of lunatics, though. Look at Sir Oswald Mosley and his boys, for instance. If anything, they resemble overgrown Boy Scouts.’

Lucy sat still, barely daring to breathe. What if one of the ladies turned and asked her opinion on the subject? She didn’t hold an opinion on the subject. She simply knew nothing about the subject.

What would they think of her then?

They didn’t ask her, though. Nor did they throw a single glance at her.

‘Mosley is still bitter because the Labour Party didn’t want to listen to his proposals,’ Charity observed. ‘To be honest, I thought he would have calmed down by now. All these marches and chants won’t get him back into power – they simply make him look ridiculous. If he was impressed by the Italians so much, he could have just taken up fresco painting.’

Breathe deeper, Lucy told herself. It isn’t the end of the world. If you don’t know it, you can always read about it.

‘Do you know, though, that even his mistress calls him The Leader?’

‘Alexandra Metcalfe?’ Charity frowned. ‘I thought better of her.’

‘No, the Mitford girl.’

‘Diana? The one who took to wearing her tiara on her neck?’

‘That one.’

‘Oh, heavens. She doesn’t call him that to his face, I hope? Otherwise their nights together must be the stuff of nightmares.’

‘Diana herself clearly doesn’t think so. I’ve heard, he is quite … Oh, Charity, look! We are making poor Lucy blush!’

Never did Lucy hate her fair skin as fiercely as she did at that moment. Her fingers squeezed the dainty porcelain cup with unnatural rigidity.

How she loathed her innocence. Her inexperience. Her diffidence.

She didn’t want to play the part of a timid, ignorant country girl – the role that seemed to have been assigned to her the moment she stepped into her first ballroom.

But what could she do?

‘Let’s not be cruel.’ Charity smiled. ‘We don’t want the poor girl to spontaneously combust, do we? Better tell me now about your champagne safari, Nora. I’ve always wanted to learn about it.’

‘Well, I wouldn’t go quite so far as to call it a champagne safari, but it was comfortable enough. I was fortunate to find a good hunter, though. You wouldn’t believe what an exhausting enterprise it all is! He helped me to manage that army of porters, servants, and gunbearers, not to mention the actual hunt, of course …’

At any other time, Lucy would’ve been delighted to hear the story of Nora’s adventures in the African wilderness. However, now she felt a strange uneasiness, as if the sunlit brilliance of her surroundings had diminished somehow. The thoughts of Italians and Blackshirts, and Oswald Mosley with his dark uniforms and radical ideas refused to leave her mind.

I will find it all out by the time of our next meeting, Lucy promised herself. If only to understand their jokes.

Chapter One

County of Northumberland, February 1934

Hester immediately braced herself for the furious wind as she stepped out of the car. As usual, the expectation didn’t fail her; it seemed to be cutting through her coat, through her jumper, through her skin, and chilling her straight to the bone.

Perhaps, though, car was too elegant a name for that vehicle. More than anything, it resembled the small blue vans that butchers in her hometown used for deliveries.

It also smelled oddly of hounds.

Instinctively, Hester reached for her suitcase; however, the chauffeur clearly intended to carry it for her all the way to the house. Not that she minded the courtesy too much; her hands ached after clutching the suitcase during the day-long journey, and having help made a pleasant change. However, seeing her belongings in someone else’s hands made Hester feel somehow vulnerable, almost naked.

Trotting along the gravel path, Hester raised her eyes. There it was, her home for the next several years: the massive stone bulk of Hebden Hall.

There were plenty of things one could say about this house. You could accuse it of being unwelcoming, forbidding, old-fashioned, or even eerie. But no one – at least, no one Hester knew – could level against it the charge of being unimpressive.

Like a medieval cathedral, this stately home must have been designed to inspire awe and a little fear in the hearts of visitors. If that was the case, Hester couldn’t help but give the unknown architect his due. He had clearly succeeded.

The oldest part of the building, where the walls were dark with age and tinged with green, was crawling with strange creatures. They leered at Hester from above, the eternal captives of stone. Some of them resembled cruel dogs; some seemed closer to hungry lions.

Gargoyles, Hester remembered. They are called gargoyles.

The main entrance glared at her, impossibly grand and preceded by a tall staircase. For a single wild moment, Hester thought that she would have to come through these forbidding doors.

But no, of course not. The fear was unfounded; furthermore, it was silly. The chauffeur, whose name she was too shy to ask, was already turning to an obscure door covered with green baize.

‘The servants always come in here,’ he explained, giving her the suitcase back. Hester took it with an ill-concealed relief. ‘Don’t you worry. We are almost there.’

On the other side of the door, the silence of long, half-lit passageways greeted Hester. Her escort’s energetic footsteps rang unnaturally loudly in this hollow maze. Half ashamed of her own unease (what was she, a child in the darkness?), Hester tried her best to keep up with him. The thought of getting lost in these corridors was terrifying in more ways than one. After all, she was tired, and the possibility of her rest being delayed still further was almost as frightening as the gargoyles outside.

Their way ended in an enormous kitchen. Hester was seated, a blissfully large cup of tea thrust into her hands. Not wasting any time, she put the cardboard suitcase securely by her side. Hester looked up with silent gratitude at the tall woman who greeted her in the kitchen.

‘You must be quite tired after the journey,’ the cook observed.

Hester half expected her to sit down beside her; however, the woman continued to stand with the rigid dignity of stone.

For some strange reason, Hester had always imagined cooks – particularly cooks in such grand households as this – to be plump, sturdy, motherly creatures. Mrs Mullet, however, was none of these things. Hester found herself wondering how she even managed to lift all the menacing-looking saucepans, let alone work with them for hours on end.

‘To be honest, I am. It took longer than I expected. Thank you so much for the tea,’ Hester added belatedly.

Really, she didn’t expect a journey of less than a hundred miles to fill all day. However, it turned out that to reach the place of her new employment, Hester had to change three trains. Of course, these were not the shiny new expresses, which could take you from one end of the country to the other in a matter of hours; the steam-powered trains used for local needs must have remembered Queen Victoria as a happy newlywed.

It didn’t diminish Hester’s excitement, of course. Ever since she’d left home, she had been clutching her thick cardboard ticket as if it designated her straight to Paradise. In the smoky refreshment rooms of every station she told the other bored travellers: ‘Me? Oh, I’m going to take up a new job. I will become a lady’s maid in the Earl of Hereford’s household. You must’ve heard of them: their seat is Hebden Hall. Such a grand place.’

Strictly speaking, Hester was to become merely a young lady’s maid; that is, she was going to serve the Earl’s debutante daughter, not his wife the Countess. But there was no need to go into such details for the strangers in railway refreshment rooms, was there?

Mrs Mullet apparently thought that the newcomer had had enough rest, and was more than ready to hear the list of her duties. The cook (or, rather, now she was in her capacity of housekeeper) went over each point with metallic precision and years-honed confidence.

‘The breakfast tray is to be taken upstairs at eight. The young lady is an early riser.’

Hester, having relaxed too much in the suffusing warmth of the kitchen, now leaned forward and listened closely. The meticulous list of times and things to do was growing threateningly, and Hester felt the slow burn of fear lest she forget anything.

‘I am afraid you’ve arrived a little too late for Lady Lucy to meet you now,’ Mrs Mullet added with a note of genuine regret in her voice. There was also a hint of reprove, as if the country trains might have done well to be a little more considerate of her lady’s time. ‘Abigail will take you to your room. I wish you a good night’s rest, Miss Blake.’

She didn’t add, ‘You are going to need it,’ but the heavy implication seemed to hang in the air.

Unwilling as she was to steer herself from the brightly lit kitchen and her warm cup, Hester nonetheless took the hint. She stood up, took the long-suffering suitcase, and followed sprightly Abigail into the gloomy maze of corridors.

Was she actually called Abigail? Hester wondered. Her uncle used to serve in the magnificent household of Lord Londonderry, and, according to him, a lot of masters had a propensity for giving their servants ‘smarter’ names. He was once rechristened Charles, and plenty of maids went by the name of Abigail.

‘But don’t you worry, Hettie,’ he said. ‘They don’t do such things any more. Not to ladies’ maids, anyway.’

It might have been true, of course. After all, he went into service way before the war started – therefore, as far as Hester was concerned, in unimaginable antiquity. He was hired as one of the ‘matching’ footmen, chosen for their impressive height and build. Lord Londonderry had, it seemed, very particular aesthetic preferences; his housemaids were also invariably tall. Hester’s uncle was to wait upon bejewelled guests during most splendid receptions. His hair, like the hair of the other footmen, was powdered, his gloves spotless.

Departing for Hebden Hall, Hester half expected to find a similar grandeur here. That was silly, of course. The sheer fact that Mrs Mullet the cook also had to take up the duties of a housekeeper said enough.

Abigail’s smile was tinged with compassion as she opened the door for her. Nodding gratefully, Hester stepped into the room – and, for the first time in this impossibly long day, found herself surrounded by silence.

The simple outlook of the room would’ve been dear to the hearts of ancient Spartans. However, the fact that she had her own room was a pleasant surprise all by itself.

It was strange to think of it now; but, as Hester reminded herself, this was going to become her home for the next two or three years, at least. Therefore, she had better start getting used to it.

Waving exhaustion aside, Hester began unpacking.

First things first, of course: print frocks, sturdy shoes, sensible woollen dresses. Hester was fortunate: unlike poor Abigail, she was spared the need to wear the uniform, the lace bonnet, and clean aprons. However, there were still certain rules she had to abide by.

Hester grieved silently for her red lipstick. But then, she usually only wore it to dances, anyway; there would be no dances here.

The frocks looked pleasantly new, sewn only last week. The fabric felt encouragingly fresh beneath her fingers.

The turn of treasures came only when the necessities were unpacked and hung.

Hester carefully placed the postcards upon her table; they seemed to glow with colour in the grey strictness of the room.

The landscapes of Java, the boulevards of Paris. The purple of imperial palaces, the green of Alpine slopes, the white of the sea foam. Dazzling, vivid windows into other worlds.

And now, Hester was closer to them than she had ever been.

Her heart was thudding in her chest, but this time it was thudding with pleasant anticipation.

Yes, she was closer to her dream than ever before. And she would reach it one day; yes, she would reach these enigmatic shores, the exotic and the urbane. Whatever cold nights and mind-numbing efforts it took.

The stack of letters, tied with a pretty red ribbon, was the last thing she unpacked.

***

Hester couldn’t have imagined the stairs to be so long.

The breakfast tray was a deadly weight in her hands. She watched her every step, bathing in cold sweat every time the precarious balance of cups and plates seemed to be threatened.

Please, please, please, don’t let the door be heavy …

Her prayers were left unanswered.

When all the dangers were finally overcome, and the threshold of her mistress’s bedroom was safely behind, Hester discovered two surprises waiting for her.

The first was the room itself. Hester had somehow expected the bedchamber, belonging to the daughter of the house (and the only daughter at that) to be the epitome of silken luxury. However, it was quite as gloomy and almost as austere as Hester’s own, if admittedly grander in size. The stark white walls and sparse pieces of furniture seemed to have been left untouched since the first Earl of Hereford won his fortune in some medieval adventure.

The second surprise was the fact that all her tiptoeing and worrying was for nothing. Lady Lucy Fitzmartin, the daughter of the ninth Earl of Hereford, was already fully awake, with her head propped on a pillow, her night-black hair spread across it like a net.

And she was smiling.

‘Why, good morning!’ she said, turning her head to the newcomer. Her eyes were wild with delight, as if she had awaited this visit for hours. ‘I hope I didn’t startle you.’

‘Not at all, my lady,’ was all Hester managed to say.

‘Good.’ Lady Lucy nodded. ‘The rainfall must have wakened me, and then I simply couldn’t fall asleep again. My thoughts never allow me to.’ Was her tone apologetic? ‘You are Blake, aren’t you?’

No smart new name for her, Hester remembered. Only a surname.

‘Yes, my lady.’ She set the tray down, dutifully careful. ‘I arrived yesterday evening.’

‘Yes, yes, I’ve heard about it. And how do you like Hebden Hall so far?’

Hester hesitated. It wouldn’t do to lie to her young mistress, of course. And, in any case, she was a terrible liar.