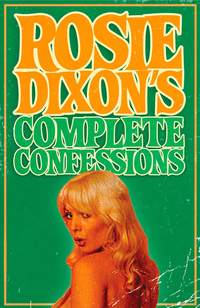

Rosie Dixon's Complete Confessions

“Not just soot,” says Labby enthusiastically. “Flour, custard pies, fire extinguishers. Last year St Swithin’s had a tank on the pitch. It got out of control and ran over an invalid car. God, it was funny.”

“Sounds a riot,” I murmur. “What about the bloke in the invalid car?”

“Oh, he got out in time. Caught the chap standing up in the tank behind the ear with his crutch. I thought I’d die laughing.”

“Like the geezer in the invalid car.”

“Don’t be so serious, Rosie. It’s only a bit of fun.”

Two weeks later, Labby is in raptures and Tom is practically ruptured. Nurse Bias’s beloved has received his injury plunging over the line for the winning try against Northminster Hospital in the semi-final.

“Dirty swines did it out of sheer spite,” hisses a furious Labby. “He’d already grounded the ball.”

“Looks as if his balls are going to be grounded for a bit, doesn’t it?” I say cheerfully. “What are you going to do?”

Labby does not find this amusing. “I’m thinking of the team,” she sniffs. “They’re going to need his thrust in the middle.” There must be an answer to that but I am too refined to consider it.

“He certainly has a good eye for an opening,” I say, thinking of Christmas and Nurse Wilson.

I have forgotten about being a cheer leader when Labby produces a black mini skirt and a matching jumper with a big gold A and a snake embroidered on it.

“We’re the Adders,” she says. “Adder-laide. Get it?”

“If I think about it for fifteen minutes,” I say. “Blimey, do you want me to wear that? It’s a bit short, isn’t it?”

“You’ll have to get used to the remarks. They’re always going on about ‘I’ve adder’ and ‘she’s been layed’.”

“Sounds just like University Challenge, I can’t wait. By the way, have we got any chance of winning this game?”

Labby looks glum. “We got thrashed last year. They take it so seriously, you see?”

What the hell do we do? I think to myself. Apart from moving all the patients into the grounds and turning the wards into gyms I can’t imagine what more can be done.

Comes the great day and Labby has not slept a wink the previous night. I know because her tossing and turning has meant that I have not slept a wink either. I go through my morning on the ward in a daze and am so absent minded that I allow myself to wander within grabbing distance of Britain’s sexiest octogenarian. The dirty old basket is suggesting a game of “naughty nanas” before you can say “straitjacket”. At least it is nice to know that I have one fan. Groper Arkwright may not be God’s gift to women but he is loyal.

There are three coaches to take supporters to the ground and I feel a right twit sitting there in my cheer leader uniform. We have had one rehearsal and it was disastrous. I don’t think I will ever be able to put my heart into any song that ends “Right up, Queens!” The whole thing is not calculated to make your blood turn into red steam:

“Adder, Adder, Adder, Adder,

Adelaide’s! ! !

Come on Queens, give them beans!

Right up, Queens!”

I was furious because Adam Quint walked past as we were prancing about. He stopped and watched us with his hands on his hips and the expression on his face made me want to punch him in the mouth. It was like Einstein watching a group of monkeys trying to thread beads on a piece of string. I don’t think I will ever be able to find the words to describe how much I loathe that man.

The match is to be played at Richmond and I tell Labby that this is a good omen because of Tom’s name. She tells me that Tom was playing there last year when the hospital lost 32–0.

“Better close the windows,” says someone, and I see why when a bag of soot bursts against one of them as we drive through the gates of the ground. There are long red and white scarves everywhere and these must obviously belong to the St Swithin’s people. I can hear shouts and screams coming from behind the stand and a man walks past me covered in bog paper with a toilet seat round his neck.

“It’s a scream, isn’t it?” yodels Labby. “Olly, Olly, Adders! !” Everybody surges out of the coach and I am grateful to the medical student who passes me a hip flask and urges me to take a swig. I am feeling about as nervous as a sword swallower with hiccups. My last public performance was in a Butlin’s Holiday Princess Contest and my bra fell off. The girl who won the heat was the one who had hooked me up. Just a coincidence, of course.

“How long do we have to stay out there?” I ask.

“Until the game is over.”

“What!? I though we just did our little song and that was that.”

“Oh no. We go behind the goalposts and enthuse the team.”

I wish someone would enthuse me. It is a freezing cold afternoon with a hint of snow in the air. My reception area is like a cold storage unit and I have still got my coat on. Where is that medic with the hip flask?

Out on the field, rival gangs of supporters are pelting each other with paper bags full of soot and flour and parading banners with slogans like “St Swithin’s for Cuppers” or, the brilliantly original, “Queens are Kings!” The main idea seems to be to destroy as much of the opposition’s material as possible and the spectators beginning to fill the stands rehearse their cheering as the battle rages below them.

I try and keep out of trouble and wrap my arms round myself to stop my nipples becoming petrified prune stones. If I brushed against something hard they might snap off.

“We’ll get going just before the team comes out,” says Labby. “Oh look! The boys have got a fire engine. Isn’t that brilliant?”

She is right. There is a fire engine carrying the black and gold Queen Adelaide’s’ colours circling the pitch. It looks quite a new one too. I don’t suppose—I look towards the gates and there is a man in a fireman’s hat struggling with a group of medical students. Oh dear. This is becoming a bit like the Christmas Dinner. At least the fireman seems to have been separated from his chopper.

The extending ladder on the fire engine swings out and two rows of St Swithin’s supporters in the stand collect a faceful of foam as a Queen Adelaide’s medic unleashes a fire extinguisher from the, top rung.

“Fantastic!” Labby’s ecstasy is short-lived. The tip of the ladder strikes the end wall of the stand and spins round nearly catapulting the Queen Adelaide’s marksman into the standing spectators. He dangles for a moment and then drops onto the grass.

“Is he all right?” We sprint towards the prostrate body with a crowd of Queen Adelaide’s supporters but are beaten there by an ambulance that appears from nowhere. The authorities are obviously well prepared for this game. The back doors swing open and—ooooow!! Four St Swithin’s swine leap out and start spraying us with their own fire extinguishers. A tremendous pitched battle takes place and reinforcements converge from all sides. Another ambulance screeches up, but this time we are ready for it. Almost before the doors are open the driver and his mate are covered from head to toe in flour and soot. It is only then that we realise they are on the level. Labby tries to say something but I don’t think they are very pleased. Especially when the bloke they came to pick up, walks off whistling.

“I think we’d better go and do our thing,” says Labby. “It sometimes gets a little out of hand about now.”

I can see what she means when they break the banner over the man’s head. As I recall it, the motto of Queen Adelaide’s is “Cure by faith and dedication.” It must be referring to bacon.

Whatever anyone may say about our performance of the Queen Adelaide’s’ song—and most people seem to say “get ’em orf!” (referring, I believe, to our knickers and not the performers themselves)—it does seem to divert attention from the violence on the field—that and a loudspeaker announcement saying that the fire brigade want their fire engine back and that the police have been called. By the time we have got to the “Right up, Queens!” bit and swung our snakes—I didn’t tell you about those, did I? I was too embarrassed—we are actually being cheered by both groups of supporters. It just shows what fourteen legs, fourteen tits, seven cloth adders and one lousy song can do to restore international understanding. Maybe the United Nations would like to employ us. The wail of police sirens coincides with the last notes of the song and the Queen Adelaide’s team runs out onto the pitch. It must be whatever was in that hip flask, or the reception to our song, but I actually find myself cheering.

They all look so big and strong and healthy and the whiff of embrocation would kill the editorial board of Jeremy at forty paces. Even when Shameless MacSweeney squeezes my pussy as he canters past I am not annoyed. “Just a touch of the magic minge to bring me luck,” he husks. “The Irish are very superstitious, you know.”

“Hurrah!” shouts Labby. “Doesn’t he look fantastic?” She means Tom but my attention is seized by the large, hairy figure shambling out onto the pitch behind the rest of the team. It is Adam Quint wearing rugby kit. He looks like Clement Freud with elephantiasis.

“He’s not playing, is he?” I gasp. I mean, with the gut he has on him it is easy to see why his socks are round his ankles: he can’t bend down to pull them up.

“John Hockey had to drop out at the last moment,” says Labby sadly. “I believe Quint used to be very good when he was at school.”

“He must have been the boy who first picked up the ball and ran with it,” I say, gazing at the flesh mountain ambling paSt I must have spoken too loud.

“If you think I look ridiculous you should take a look at yourself in the mirror. I’ve seen Christmas tree fairies with more chic.”

As usual he is gone before I can think of anything to say. God but I hate that man. He spoils the look of the whole team. The rest of them are all whirling their arms in the air and running on the spot with their knees slamming against their chests. He is peering down the front of his shorts. It does not inspire a lot of confidence.

The St Swithin’s team run out and it is obvious that they are much bigger than us. Bigger and uglier. No, honestly. They really are repulsive, some of them. Our team look much nicer. Even Quint looks cuddly compared to some of the bruisers on the other side.

The two teams are presented to an old man in a white fur coat—at least I think it is a white fur coat until I realise that someone has tipped a bag of flour over him—and then it is time for the kick-off.

The ball is placed on its end in the middle of the field and one of the St Swithin’s men kicks it towards where all the Queen Adelaide’s men are standing. I think it would have been much cleverer to kick it over to the other side of the field but I suppose he knows what he is doing. The ball is caught by one of the Queen Adelaide’s team and then everybody starts punching each other and the referee blows his whistle. It is just like the scene before the game.

When the players break up I see that Quint has the ball and a bleeding nose. I would have backed myself to start a whip round for anyone who gave Quint a bloody nose but to my surprise I feel quite angry. When he puts a giant mitt over the face of one of the St Swithin’s men and pushes him flat on his back I am thrilled. “Belt him one!” I shout.

Labby looks horrified. “You don’t say things like that at rugger matches,” she says.

“I do,” I tell her. “Smash his face in!”

If anyone had told me that rugby was just like the wrestling on the telly I would have been a fan years ago. Mick McManus would really have to watch himself with this lot. Fists, elbows and boots flail away, interrupted only by dull moments when the ball is kicked in the air or people try and run with it.

“I think we’re holding them up front,” says Labby, breathlessly.

“Is that why that man is lying on his back clutching his balls?” I ask.

“Our back row is up very faSt”

“Given half a chance,” I think she is talking about MacSweeney.

“You mean the ref? He is a swine, isn’t he?”

There is no doubt that the referee favours St Swithin’s and this is proved after ten minutes when he awards them what Labby tells me is an easy penalty kick.

“What a swizz,” she says as the stretcher goes paSt “I’m certain Tom never meant to stand on his face.”

“Don’t worry. Maybe he’ll miss it. Does the ball have to go over or under the bar?”

I start booing the minute the St Swithin’s man runs up to kick, but again, Labby is horrified. Apparently, you don’t do that kind of thing either. It is so confusing. Throwing bags of soot and punching lumps out of each other on the field is O.K. but a bit of verbal agro is out of the question.

The kick is successful and we are three points down. All the St Swithin’s supporters go wild and I would like to scratch their stupid eyes out.

“Let’s go behind the posts they’re attacking,” says Labby. We move off along the edge of the field and I give a V sign to the jeering St Swithin’s mob. Labby shudders. Of course I am not usually like that but I do get worked up sometimes.

Quint is standing on the touchline and his vast tummy is quivering. His hair is bedraggled and blood mats his beard. I feel almost sorry for him. Queen Adelaide’s kick off and Quint shambles forward and flattens the man who is about to catch the ball. Immediately there is a shrill blast on the referee’s whistle and the St Swithin’s supporters start shouting ‘Off! Off! Off!’ I think they are referring to Adam but it is the St Swithin’s man who leaves on another stretcher.

“Come on, boys! Only another thirteen to go,” I shout. Labby winces.

In fact it is soon thirteen–fourteen because one of our team has to go off with a cut head. He collects a boot that is intended for Quint.

“A certain amount of feeling is creeping into the game,” says Labby.

“Is that why that other man is lying on his back clutching his balls?” I ask.

Labby does not have a chance to reply because sickening St Swithin’s score a try.

Tom Richmond cleverly kicks the ball in an opponent’s face but it bounces over our line and a St Swithin’s man falls on it. Quint falls on him but too late to do more than make him the third stretcher case of the day. Another four points to St Swithin’s. It is absolutely sickening. A couple of minutes later I feel even worse when St Swithin’s convert their try and make the half-time score 9–0 in their favour.

“If we can knock out another three men we’ve got a chance,” I say. “They’re already down to twelve.”

“I expect that’s what Mac is telling them,” says Labby.

Shameless is pounding his fist against the palm of his hand and making faces like he wants to go to the toilet very badly. Five minutes after half-time, he gets his chance when he is helped off the field clutching his collar bone and saying that he does not want to go—off the field of course.

“That’s terrible,” says Labby. “He’s one of our best players.”

“Olly! Olly! Adders!” I scream, “Let them have it, boys!” We do another little dance and a chorus of “Right Up, Queens!” but it looks more like “All up, Queens” out on the field.

Both sides have slowed down a lot and poor Quint looks exhausted as he struggles from one side of the field to the other. The St Swithin’s supporters are doing all the shouting and with twenty minutes to go we are still trailing by nine points.

Then something amazing happens. Queen Adelaide’s score! Somebody kicks the ball down the edge of the pitch and the St Swithin’s man who is running after it slips over—he says later that he was tripped but of course he is a rotten fibber. I may have stretched out my foot and wriggled my toes because I was getting pins and needles but there was definitely no intention to trip him up. He falls into the crowd and a Queen Adelaide’s man picks the ball up and runs under the posts. It is so exciting and we all cheer like mad.

The St Swithin’s supporters reveal what lousy sports they are because they all shout and boo and wave their fists. It is all so petty. Tom Richmond kicks the ball over the bar and we are only three points behind.

“A try will do it,” squeals Labby. “Oh, come on, Queen Adelaide’s.”

Now that we have scored the boys throw everything that they have got into the game and I notice what a tower of strength Adam Quint is in the touchline queues—or lines out as they call them. He is the biggest man in our team and he leaps into the air and catches the ball like a great seal. Of course everybody has to wait a couple of minutes for him to get to each line out but I expect that they are glad of the reSt

“How much longer?” I say to Labby.

“Three minutes. But there must be some injury time.”

“About half an hour, I should think.”

Even as I speak another St Swithin’s man goes down clutching his face and his team-mates start throwing punches at Adam. It is so unfair. They are always picking on him!

“Pick on someone your own size, you apes!” I scream.

“But he’s twice as big as anyone else on the field,” protests Labby.

“Exactly.” It occurs to me that for some stupid reason I care about the big rude ape. It must be hospital spirit.

A free kick is given against the Adders and immediately St Swithin’s nearly score again. One of their gorillas grabs the ball and runs away with it after he has punched Tom Richmond in the face. It is an obvious foul and the referee must be bent not to blow his whistle. Fortunately, a brilliant tackle by one of our players stops the horrible little jerk just short of our line.

“Why is he going off?” I ask. “Has he hurt his arm?”

“He’s been sent off, you stupid bitch!” snaps a St Swithin’s supporter with a face like a frog’s death mask. “Even this ref draws the line at short arm tackles. You’ve got the dirtiest team I’ve ever seen in this competition.” I do not want to get involved in unpleasantness so I wave a couple of lady-like fingers at the foul-mouthed fink and prepare to watch St Swithin’s make the game safe with a simple penalty kick. Maybe their kicker gets cold waiting for his fourth team-mate to be carried off the field because he makes a balls-up and hits one of the uprights. The ball bounces back and Adam catches it. He moves with the speed of treacle flowing down a fly paper but manages to give the ball a most terrific kick just before all the St Swithin’s swine leap on him. The ball soars through the air and, helped by the wind, lands deep in the St Swithin’s half. Everybody chases after it but just before Tom Richmond can get a boot to it some snivelling little St Swithin’s rat kicks it off the pitch by the corner flag.

As Adam struggles to his feet I see the referee looking at his watch.

“This must be our last chance,” croaks Labby. “Oh, come on, Adders!”

Adam Quint shakes his head and runs towards the line out and I find myself responding to the look of grim endeavour that blazes in his eyes. He brushes aside the referee who comes up to ask him if he is all right and shoulders his opposite number three feet out of the line as he takes up his position. He bends forward so that his right hand is resting on his knee and his great belly quivers menacingly. “Come on, Adam!” I murmur the words under my breath but I couldn’t feel them more strongly if I was shouting them at the top of my voice.

The ball curves through the air and Adam leaps, one arm soaring higher than anyone else in the line. He hooks the ball down and seizes it with both hands. What a man.

“Give it!”

Adam makes as if to pass and then hunches his shoulders and halves his height. With an explosive yell he hurls his whole weight against the wall of flesh between him and the line. There is a landslide of bodies and the referee’s hand shoots in the air. We have scored! Everybody is going mad and Labby runs on to the field to embrace Tom. For two pins I would do the same to Adam. Adam Quint. Suddenly the name trips off the tongue like Mark Phillips.

My hero stumbles back to the centre line wiping the blood from his mouth with the back of his hand and Tom prepares to take the conversion. He misses but it does not matter. The final whistle goes immediately afterwards and Queen Adelaide’s have won 10–9 and 13–11 if you include the number of people left on the field at the end. I can hardly believe it has really happened.

A crowd of Adelaide’s medics pour on to the field and try to chair Adam off but he shrugs them aside and runs from the pitch. It is the fastest I have seen him move all afternoon.

“There’ll be the most fantastic party, this evening,” trills Labby. “Oh, I’m so excited I think I’m going to burst”

The two teams clap each other off the field and the cup is presented to Tom Richmond. Feeling rather sad, I start walking towards the bus. Labby is staying behind to be with Tom and I wish I had a boy-friend in the team. I can still see Adam Quint poised to spring … the moment when he burst over the line with half the St Swithin’s team on his back … the agonising seconds before the referee raised his— “Hey, Nurse, can you give us a hand? I think this bloke’s in a bit of a mess.”

The speaker is standing at the back of an ambulance. The doors are open and I can see someone bending over a stretcher.

“What do you want?” I say, going over.

“You, darling!”

Before I can cry out or make a run for it the figure bending over the stretcher grabs my arm and yanks me into the ambulance. A blanket is flung over me and by the time I get it off, the doors are closing behind me and the ambulance is drawing away. On the floor is a St Swithin’s scarf. I have been kidnapped!

I batter on the sides but I make less impression than Enoch Powell singing “That coal black mammie of mine,” at the Brixton Civic Centre. There is a babble of voices, and then my cries are swallowed up in the mighty roar of London’s traffic. I am not frightened—just furious. Everybody else wil be having a great time back at the hospital while I am stuck with a load of twits from St Swithin’s.

A long half hour later, the ambulance stops and the engine is turned off. We must have arrived. The doors open and the creep who first called to me bows low.

“Welcome to London’s number one hospital,” he says.

“That doesn’t mean much coming from London’s number one twit,” I snarl. “How long do you intend to keep me here? I get bored easily in the company of jerks.”

“Sticks and stones may break my bones,” says the drip. “But words will never hurt me.”

“O.K. Give me some sticks and stones,” I say. “And get a move on. I have millions of better things to do than hang around swopping B movie dialogue with you.”

“You’re going to stay here till Queen Adelaide’s hand over our cup. You won it by cheating.”

“Can I use the telephone?” I say, “I’d like to call a child psychiatrist to have a look at you two.”

I have been brought to what looks like the back entrance to a block of flats and I imagine that it must be a hall of residence for the medical staff of St Swithin’s.

“Come with us and don’t try anything clever,” says the one who does all the talking.

“You wouldn’t be able to follow me if I did,” I say.

“Why don’t you let me go now instead of a couple of hours later? I know your evening has been ruined. Why spoil mine?”

Good sense gets me nowhere with these creeps and I am led to a lift and taken up to the fourth floor. I would not mind so much if my captors were a teeny bit attractive but they make Julian Orchard look like Charlton Heston. I am led along the corridor to room 302 and ushered inside. It smells of Old Spice and old socks—like most bachelor’s rooms. Not, of course, that I am an authority on the subject.

“Would you like a glass of sherry?” says my first captor.

“I don’t know. I’ve never tried one.” This is not true because I had some at Aunty Lil’s wedding. I can remember that I did not like it much—I did not like the wedding much either. The best man flashed his nasty at me while they were signing the register. Of course, he and the bridegroom had been drinking since the pubs opened—if you had seen my Aunty Lil you would know why.