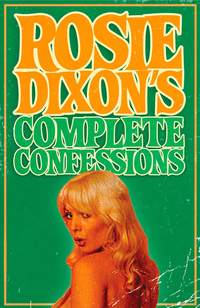

Rosie Dixon's Complete Confessions

“She says the key to the medicine cupboard is under the Victor Ludo plaque.”

“Don’t you mean ‘Victor Ludorum’?” I ask.

“Not at St Rodence,” explaines Penny. “Ludo is the only game we can get the whole school to play.”

“And then only if we allow gambling,” says Miss Batson. “It causes so many problems.”

“Last year we had outside intervention from gangsters. There were attempts at extortion and threats of violence,” says Penny.

“How awful! What happened?”

“In the end the gangsters paid up. But it was pretty nasty while it lasted.”

“There’s going to be none of that, this year!” snaps Miss Murdstone. “This year we’re going to have a proper sports day.”

It is amazing how quickly people can change. Miss Murdstone used to be the only member of the common room prepared to stand up to Miss Bondage. Now she sounds just like her.

“You mean running and all that?” says Miss Batson.

“Yes ‘running and all that’, with an invitation going out to the parents. Have you got any objections?”

Miss Batson wriggles defensively. “No, of course not. I was just remembering the cross country, that’s all. Of the hundred and five girls that passed the medical, eighty three went through the gates and the first girl back came in five weeks later.”

“In a Black Maria,” adds Penny. “Thirty eight of them were never seen again.”

“We did get that postcard from Port Said,” says Miss Honeycomb. “Very pretty it looked with the palm trees and—”

“Fiddle faddle!” Miss Murdstone brings her fist down smartly on Jill Batson’s crumpet. “I’m not talking about a cross country. I’m talking about a properly organised sports day, Green, Dixon, that’s your province.”

Penny sucks in breath. “It’s not going to be easy to arouse enthusiasm whatever we organise. If you remember our last sports day, the only event that attracted any interest was throwing the javelin.”

Miss Honeycomb winces. “Poor Miss Marrow. Is she out of plaster yet?”

“I believe she’s doing as well as can be expected,” says Miss Murdstone. “No, I don’t think we’ll include the javelin in this year’s programme. And that goes for the other field events as well. Anything that can be thrown is out.”

“Long jump is all right, though,” says Miss Batson.

“Provided we can find someone who can reach the pit. It was pathetic last year.”

“How about the high jump?” I ask.

“First prize went to the first girl who was able to clear one of the hurdles without assistance.”

Penny shudders. “That was terrible, wasn’t it? The race took twenty-two minutes and in the end we had to lay all the hurdles flat. Even then, half the field failed to finish.”

“And the winner was disqualified for taking stimulants—”

“—During the race.”

“Are you sure you want to go ahead with this?” says Penny levelly.

Miss Murdstone swallows hard. “I have made a decision and there is no going back on it. There is a good deal of untapped vigour in the school. Since Miss Bondage’s departure and the decision not to proceed with the Commando Training Group it needs an outlet.”

Her words are interrupted by another burst of small arms fire which removes three panes of glass at the top of the window. Miss Murdstone moves swiftly and courageously to the shattered casement. Below us, a small girl with a smoking sten gun is picking up the remains of a wood pigeon.

“Right, Deidre! You will write out fifty times ‘I must not fire at birds flying across the face of the school buildings’.” Miss Murdstone turns to the rest of us triumphantly. “There, ladies! I think that makes my point more tellingly than any words. The girls need an outlet for their surplus supplies of physical energy and a sports day will provide it. I will draft a letter to the parents today.”

There is no arguing with her and I secretly curse Deidre Hoareflooting for discharging her weapon at such an inopportune moment. Shooting is forbidden during chapel, anyway.

“We’ll have to run heats and make it compulsory for every girl to go in for three events,” says Penny. “We’ll never get anybody to enter if we ask for volunteers.”

“Are parents likely to turn up?” I ask.

“I’m afraid so,” says Penny. “It’s one of their few chances to be snubbed and insulted by Miss Grimshaw in person. And, when you pay over a thousand a year for the privilege you don’t want to miss it.”

“Do you think she’ll be all right?” I ask.

“She has a marvellous sense of self preservation. If she smells a governor or a school inspector she can sober up in a moment. Parents have almost the same effect.” Penny is so unkind. She is always pretending that Miss Grimshaw is an alcoholic. I don’t think it is nice to make jokes about people who are sick.

“What are the parents like?” I ask.

“All sorts,” says Penny. “They only have one thing in common. They’re very stupid. You’d have to be to send your child here, wouldn’t you?”

“Penny, you’re so cynical!”

“Not a bit of it. I’m realistic, that’s all. They’re also inclined to be rich and lecherous. I’ve known girls in the school who can boast three different fathers on Commemoration Day. Some of the parents get confused and find themselves taking last year’s wife’s children out to tea. I remember Lavinia Pope-Drooley. She went out with the wrong Daddy and married him.”

Really! It is amazing how the other half live, isn’t it? I find all this a bit shocking but Penny comes from that kind of home so she can take it in her stride.

As Sports Day approaches a feeling of tremendous apathy falls over the school. The only people showing any enthusiasm are Penny and myself, for obvious reasons, and the two Saranjit girls who reckon that they are going to clean up everything between them. This supposition is proved untrue when some joker reverses the spikes in Rumna’s running shoes so that they stick up through the soles. This is not a very nice thing to do but there is no need for her to release a hooded cobra in the showers—such a pointless gesture, too, because none of the girls ever use them—the showers, I mean. The only person to go in there is Mr Chaney, the school caretaker, who is trying to grow edible toadstools. Prayers were offered up for him in the school chapel and he is said to be as well as can be expected. The hooded cobra died.

“Obviously the work of a race gang,” says Penny when she hears about the spiking.

“You mean, because she’s Indian?” I say, horrified.

“Not that kind of race,” says Penny contemptuously. “Everyone hates everyone else here, regardless of race, colour or creed. I was referring to the girls who run the gambling syndicates. If a lot of girls back Rumna and she doesn’t run the bookies will keep the stake money.”

“That’s awful,” I say.

“It certainly is,” says Penny. “Thank goodness I’ve got my money on her sister.”

I ignore the implications of this unsavoury remark and concentrate on learning more about the organisation of this most important event in the school calendar.

“Do the parents have tea?” I ask.

“Very few of them. A cup of lukewarm gin is more their scene. Usually it’s a quick look round the school and back to the hamper. The more thoughtful parents know that the more they eat the less their children will have in the weeks to come.”

“When you put it like that I don’t know why anyone should want to send their child to a school like St Rodence.”

“It’s in the blood,” says Penny. “The ancient Spartans used to leave new born babies on the side of a mountain. If they survived they were reckoned to be Spartan material. The English private school system is based on the same lack of principle. Then of course there is the English literary tradition. Schools like Dotheboys Hall and Lowood have persuaded parents that such founts of misery are part of a child’s cultural heritage.”

“Yes,” I say. I don’t really understand what she is talking about but I don’t want to appear dim. “So the parents don’t play any part in the proceedings? There isn’t a fathers’ race or anything like that?”

Penny shudders. “Even worse: there is a parents’ obstacle race. Everybody loathes it but it is a school tradition—about the only one the school has, apart from not paying the fees.”

“Who sets it all up?”

“Oh, Seth and Ruben. They could do it in their sleep.”

“Yes,” I say thoughtfully. Her words remind me that I have not been back to the pav. to pick up my tennis racket. There is something about the old man that I don’t completely trust. He keeps asking me if I would like a glass of Molderberry wine whenever I see him and flexes his elbow in a very strange fashion—at the same time striking his forearm. Sometimes I think I will never understand their country ways.

There is another distressing incident on the eve of sports day when Napum, now a firm favourite for every event in her sister’s absence, withdraws with a pulled muscle. There are rumours that an anonymous letter saying that she would be shot if she appeared at the starting line aggravated the injury. In the interests of preserving peace and quiet it is decided to ignore the rumours.

Two senior girls are attacked with hockey sticks when returning from a wood-collecting exercise and Penny prophesies that we are in for trouble.

“I think tomorrow will throw up some very interesting winners,” she says. “It was stupid of me to back a favourite. I should have guessed they would be taken out before they tucked their gym slips in their knickers.”

“You suspect foul play?” I ask.

Penny looks at me with contempt. “What other kind of play do they know?”

I suppose she is right and, of course, I had the chance to see St Rodence in action when we played St Belters at hockey, but everything is so much more out in the open at a sports meeting, isn’t it? I mean, how can anyone interfere with people when they’re running in the middle of a field? I get the chance to find out during the first event.

It is a fine afternoon by St Rodence standards and only a thin net rain is undermining the proven drying qualities of the slightly sub-hurricane force west wind. The finalists for the hundred yards are at their marks and waiting only for Miss Barton who is wrestling with an umbrella which has blown inside out. Quite a few parents have turned out and can be seen swigging eagerly at their daughters’ hip flasks.

Favourite for the race is Molly McBride, a big-boned girl from the bogs—which is possibly why she runs so fast. In the absence of the Saranjit sisters there seems no one to touch her. She certainly takes it seriously enough and has hammered in starting blocks, something quite unheard of at St Rodence where you are considered hearty if you own a pair of gym shoes.

“On your marks, get set.”—BANG!

The girl next to McBride collapses clutching her shoulder and Penny blows her whistle for a false start.

“I told you we should have got some blanks,” she says. “The trouble is that it’s so difficult to find them for a Luger. Do point the gun up in the air next time, Batters. We’re going to get behind schedule if we go on like this.”

“Stop snivelling, Pelham!” snaps Miss Batson. “It’s only a flesh wound. Goodness gracious me. I’ll have to disqualify you in a minute.”

Pelham refuses to stop crying and is led off to find matron.

“Damn,” says Penny. “I had her down for a place. There goes my each way double.”

“On your marks, get set—” McBride’s great muscular legs knot like worm casts and her shoulders lunge foward menacingly—BANG! Four of the remaining five finalists spring into action but McBride remains rooted to her blocks. She struggles gamely and then collapses flat on her face.

“What on earth!?”

We spring forward to the prostrate McBride and Penny picks up a piece of wire that is running from the starting blocks.

“Cunning little swines!” she hisses.

“Why? What happened?”

“Don’t you see? A current was passed through this wire to set up an electro-magnetic field that held the steel spikes in the girl’s running shoes to the starting blocks. She was like an iron filing picked up by a magnet.”

“Crumbs! You mean we’ve got girls who are intelligent enough to organise something like that?” I ask, amazed.

“It’s incredible what they can do when there’s money at stake.” Penny pats the sobbing McBride on the shoulder. “There, there, Molly. There’s always the high jump.”

Ten minutes later we are waiting for McBride to make the first jump. “Nothing can stop her here,” says Penny smugly. “Hey, wait a minute!” She steps forward and checks that the bar can be lifted. “Just thought I’d make sure that no joker had welded the bar to the uprights,” she says. “There’s a lot of money riding on this one and you can’t afford to be too careful. All right, McBride!”

McBride starts her high, prancing run and then suddenly twists and soars into the air. The Fosberry Flop, I believe you call it. Up, up, up and down, down, down, down, down, down, down, down, DOWN!—so far down that she disappears from view. Her scream seems to be dying away in the bowels of the earth.

“Oh my God!” says Penny. We rush to the landing pit and find ourselves looking into a deep hole. At the bottom of it is McBride. Penny’s eyes probe the darkness. “Thank heavens there aren’t any sharpened bamboo canes,” she says. “Sometimes, things get a bit out of hand.”

McBride is hauled out and retires immediately. Poor kid. Her nerve has gone and she wants to be around to count the candles on her next birthday cake.

After the high jump there are no more incidents. Five of the finalists in the egg and spoon race are found to have china eggs nailed to their spoons, and the fifth—an Irish girl—has the spoon tied to her hand, but this is small stuff compared to the serious fixing that has been going on.

With McBride gone there is no point in betting on any event because the contestants are so poor. The quarter mile race is awarded to the girl who got furthest before collapsing and the pole vault is even more embarrassing. The first competitor runs up and throws the pole over the bar. What is worse, most of the parents and girls cheer like mad.

“We daren’t run a dope test at this place,” says Penny. “Every single one would be positive.”

What puzzles me is that although the standard of athletics is abysmal, none of the parents seem to mind. In fact, the longer the afternoon goes on the happier they seem to be. Mr and Mrs Pelham, whose daughter was carried off to the san, seem particularly relaxed.

“Better get the trophies out,” says Penny. “I was hoping the Securicor boys would show up but I think they had enough after last year. Three of them emigrated to Austria and joined the Vienna Boys Choir.”

“You think the girls might steal them?” I ask.

“Not now. It’s got to be real men or nothing with these—”

“I meant the cups!” I say, trying to control my exasperation.

“Oh them! No I reckon you’re pretty safe. Most of the best stuff has already gone. The Securicor men are just here to impress the parents.”

I toddle off on my errand and am amazed at the crowd of parents around the trophy table. They are all talking away animatedly, and when I snatch a glance at the medicine cabinet I appreciate why. Even after the bashing it has had from the parents, it is still full of booze. There is one small bottle of T.C.P., a packet of corn plasters and eighteen bottles of brandy. It is amazing that the cupboard can stay on the wall.

“Hello, darling!” says a large florid man in a city slicker suit who I have noticed looking at me before. “Come for a little drinky, have you?”

“I’ve come to fetch the cups,” I say, picking up the victor ludo shield and reaching out for the other trophies.

“Hey! Hang on a minute, sweetheart. That cup’s in use.” The man snatches back a large rose bowl and I see that it is filled to the brim with a colourless liquid. My nostrils tell me that it is not Adam’s ale.

“That’s gin,” I say.

“With the merest hint of vermouth to prevent it becoming lonely. Tell me, my dear. What form are you in, apart from excellent?”

“I’m a teacher,” I say, absolutely amazed that anyone should think I was a pupil. I mean, it’s so flattering, isn’t it? Even when one considers the average girl at St Rodence.

“A teacher!? ’Pon my soul. Teachers have changed since I was a young whipper snapper. We didn’t have any teachers like you when I was at school.”

“Hardly surprising considering that you were at Dartmouth Naval College, Henry,” says a tall, thin lady with finger nails like sticks of melting sealing wax. She looks me up and down as if measuring me for a coffin. “You’re not trying to take our drink away, are you? It’s the first time I’ve been given one in the ten years I’ve been coming here.”

“Ten years!?” I say. “What form is your daughter in?”

“2E. She’s a slow developer.”

“Captain of Open Cast Coal Mining, though,” says her father, proudly.

“She’s wonderful with horses,” says Mummy.

“Indistinguishable, too,” says Daddy. Mummy taps him playfully with her shooting stick. Daddy screams and falls on the floor. Oh dear. I can see that this is going to be one of those difficult occasions. I do hate unpleasantness. I bend down to give assistance and notice Matron’s feet sticking out from underneath the hall stand. I recognise her by the scarlet bloomers with ‘I love Robin Day’ embroidered on them. She is snoring and clutching a half empty brandy bottle with a baby’s teat on it. It occurs to me that she must have uncovered the booze when attempting to treat Felicity Pelham. How awful! What can I do? I pull her skirt over her knees and try to think.

Suddenly, I have an idea. “Time for the obstacle race,” I croon. “We mustn’t disappoint everybody.” Of course, I don’t intend to go in for it but I feel it will be easier to jolly people along if I make it sound as if I am.

“I’ll follow you, my dear,” says Henry.

“And I’ll follow you,” says Mrs Henry. She is talking to her old man.

“Never missed a race yet,” says another civilised gent, raising the rose bowl to his lips. “By Jove, but this is a damn fine martini. It’s the vermouth, y’know.”

I take a look at the bottle and get a nasty shock. There, amongst the angels and coats of arms on the label it says: “Ruben and Seth Hardakre’s fine old genuine Italian Vermouth—just like momma used to make.” I hope it does not have the same effect as the girdjuice. I don’t like to think about it too closely but I sometimes have a nasty feeling that Seth and his father might have tampered with me in the thicket. It was finding my panties in my shoulder bag that first made me suspicious.

“Off we go!” I say, trying to cloak my worries in gaiety. “Good luck everybody.” I skip out of the front door and they bundle after me like patients escaping from a fire in an old people’s home. This race should be the biggest shambles yet.

“Where on earth have you been?” asks Penny when I get back to the sports field. “It’s time for the parents’ obstacle race.”

“So what do you think they are?” I say, pointing to the jostling crowd of drunks shambling towards us. “Lemmings?”

“They’re supposed to change first.” Penny jerks her head towards a group of men and women wearing overalls and embarrassed expressions.

“It gets a bit messy, does it?” I ask. It is a question I think about a lot in the months to come.

“No ratting! You come with me, my gel.” Henry grabs me by the arm and drags me towards the start line. He is obviously very much the worse for wear and I am almost relieved that Miss Grimshaw appears to have succumbed to one of her periodic fainting fits and is not looking at us. As I watch, a bottle of smelling salts is passed to and fro under her nose. She seizes it and attempts to drink greedily. What a wonderful sense of humour the woman has.

“On your marks!” The first thing I can see is six tyres dangling from ropes. They can’t expect us to go through those!

“Get set!” I try and edge towards the crowd of booing and shouting girls. Henry yanks me back.

BANG! “Tally Ho!” Henry nearly pulls my arm out of my socket as he lurches forward. “Dive!” he shouts.

By the time I realise that he means “through the hoops” it is too late to tell him what I think of the idea. Henry takes off and his features flatten against the side of the tyre so hard that the word “Dunlop” is printed on his forehead. I don’t know which is vibrating more, him or the tyre.

“Help me Henry!” Mrs H. is not a woman who is likely to drown her husband in sympathy. She tries to scramble through the tyre and her skirt splits with a noise like an elephant celebrating its win in a prune eating contest.

“Through the barrels!” howls Henry. He seems to have forgotten about the tyre and his wife. She is now hopping up and down astride a Michelin 380/180—very uncomfortable it must be, too. The barrels are in fact those crinkly oil drums and they are very hard on your knees. Almost as uncomfortable as having Henry behind you when you try and crawl through one. He does not seem to mind what he does with his hands, naughty old man!

“Along the greasy pole. Keep it up! We’re winning!”

Only just, though. It is amazing how keen these parents are. Mrs Henry’s hat has tipped over her eyes and she has abandoned her shooting stick but she is still coming on gamely. The rest of the party I picked up by the medicine cabinet are literally hanging in rags. Beautifully cut Savile Row suits are crumpled and covered in mud and one of the lady competitors has lost her skirt—mainly because Henry helped her out of the oil drum. Beside the course the spectators shout and cheer and throw empty gin bottles. It is just like one of those old sporting prints you see in other peoples houses.

The greasy pole stretches across a deep, muddy ditch and I sense immediately that it is going to cause problems—so do the hundreds of people who are clustered round it. Henry is first to try his luck and makes a brave run. He gets half way across and then his legs start moving very fast without touching anything. The column of water that rises in the air would fill a couple of barrels.

Mrs Henry is next to have a go and soon reveals what a great competitor she is. Hanging like a monkey and totally unruffled by the fact that her black frilly knickers and scarlet suspender belt are revealed for all to see she starts to pull herself across. Alas! The pole is very greasy and Mrs H. loses contact at the same point as her husband. A host of competitors now hurl themselves at the pole and there are a number of regrettable incidents as impatience gives way to outbursts of petulance. I can see where some of the girls get their aggression from. What I can’t understand is why they should be so apathetic when their parents radiate enthusiasm and will to win. I suppose that they must be reactions against all the zeal that was flying about at home.

“Take that, you swine!”

“Strike a lady, would you?”

“If you can show me one.”

“How dare you! I have never been so insulted in my life!”

“With a face like that I don’t believe you.”

In no time at all most of the competitors are struggling in the water and the race has been forgotten. Fortunately, Penny comes to the rescue.

“Forget the pole!” she shouts. “Just get to the other side and carry on.”

I know what she means by “carry on” but it is clear that Henry has ideas of his own. No sooner am I trying to scramble up the steep bank than his hands plunder my body as if trying to find pieces to take home as souvenirs.

“Please!” I say. “Everybody is looking!”

“I don’t give a damn about them. I must have you!”

If I was running fast before, now I really start moving. If the Hardakres’ Italian Vermouth had any girdjuice in it all kinds of unpleasantness could occur. The last obstacle looms up before me. It is an enormous tarpaulin under which the field have to crawl. I have half a mind to give it a miss but the old competitive spirit and the cheers of the crowd will me on. “Knickers! Knickers! Knickers!” they shout.