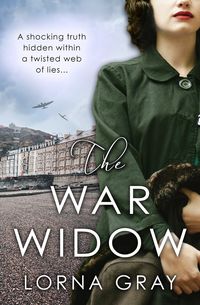

The War Widow

A division of HarperCollinsPublishers

www.harpercollins.co.uk

HarperImpulse

an imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

First published in Great Britain by HarperImpulse 2018

Copyright © Lorna Gray 2018

Cover photographs © Shutterstock.com

Cover design by Ellie Game © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2018

Lorna Gray asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008279578

Ebook Edition © January 2018 ISBN: 9780008279561

Version: 2018-06-27

Table of Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

A Letter From the Author to the Reader

Acknowledgements

Extract

About the Author

Keep Reading …

About HarperImpulse

About the Publisher

For Harry and Mason

Chapter 1

Thursday 20 November 1947

I might have done things differently had I had known today that I only had four more days of glorious solitude. That in four short days they would find me at last. That four short days would carry my race to the limit of this sea-ravaged coastline. That here I would feel the nauseating pull and draw of the waves and above it all, hear the darker overtone of footsteps as they strolled inescapably towards me.

I wouldn’t be thinking about myself at that moment. I would simply be waiting, defeated, quivering on the wooden harbour jetty and looking down into the murky water as it heaved beneath. Thinking about him and what he had done; and finally and absolutely admit that despite all my determined efforts to the contrary, I had lost control over both my mind and my freedom, with no hope left of ever regaining it.

But that would be four days from now. Today there were still four more days ahead of wonderful optimism. Today I was feeling the tug of the waves too, but in an altogether more peaceful way.

I had come to Aberystwyth in November two years after the war. I was climbing down from a rough little hilltop that overlooked the town a little after dawn and the view was glorious. The wide bay of terraces clung bravely to the curve where sweeping cliffs met dark granite seashores and today, as ever, it called to the artist in me.

I probably shouldn’t have been up there. The doctors had prescribed rest after my accident and I knew even the walk back to my hotel would have drawn their united disapproval. But at least it was quiet and calming in its way because very few people were about. Those that were cared little for a woman in a beige trench coat with the collar turned up who was walking briskly past shops declaring fresh stocks of corned beef and offal – a novelty in this time of rationing. Nobody noticed me walking past the shuttered tearooms either. These were papered with posters bearing the information that the cinema would be showing the full coverage of the Princess Elizabeth’s wedding just as soon as the newsreels got here. It was all wonderfully like being invisible. It was just unfortunate that the illusion abandoned me just as soon as I climbed the steps to my hotel.

“Good morning, Miss Word.”

The lady in the wood-panelled reception booth in the foyer was excessively genteel and her grey hair was done up in a neat bun. Her greeting was dignified and gracious but slightly marred by the fact that Word wasn’t actually my name. It was Ward but I didn’t tell her that. Just as I had been too embarrassed to correct her late last night when she’d said it after watching me sign my name on the registration form, and again after she’d taken custody of my ration book and handed me my key…

So this morning I repeated the peculiar habit of feeling guiltily responsible for having the wrong name and only stated warmly that it was indeed a good morning and moved bravely towards the dining room. It was the sort of room that belonged a largely imaginary bygone era that had never known the war. The requirement to be brave came from my reluctance to interact with the other guests. I didn’t want conversation today. And besides, the pages of the hotel’s guestbook bore the signatures of an intimidatingly large scattering of high society grandees, which I certainly wasn’t. It had prices to match. I never would have chosen to stay here at all if I hadn’t remembered it from a brief visit many years ago during my honeymoon and the fact that I couldn’t have faced any more decisions last night after such a day and such a long journey.

As it was, when I took my seat it was only to be reassuringly greeted and then ignored by two elderly ladies who were deep in an animated discussion. They were worrying about the danger of introducing unbridled enjoyment – embodied by the recently lifted embargo on foreign travel I think – to a generation that had been brought up knowing only wartime excursions to the respectable English seaside. I think they were unaware that they were, in fact, at present in Wales.

I hid my head in a book. I had borrowed it from the tiny library in the lounge next door and it was a battered copy of Jane Eyre. It was supposed to keep my mind from working while I finished my breakfast but it wasn’t doing very well since I had read the book more times than I could count. Then I discovered a more modern effort abandoned on the table next to me. It promised ‘A Sterling Mystery!!!’ – a weak pun on the name of the principle character I think – and bore the name A. E. Woolfe emblazoned across the cover like a banner. Sceptical purely on the grounds of too many exclamation marks, I picked it up and read the first few pages easily enough but when the first character died in a grisly fashion at the wheel of his car, I felt my head begin to swim and had to put it down.

“Not to your taste?” A male voice.

Looking up, I discovered that the surrounding tables were now packed with a different set of people and the comfortable Miss Bartlemans had miraculously transformed into a dark-haired gentleman who was now sitting in the chair opposite, with a newspaper spread over the table between us. His eyes were a mild pale blue and were watching me benignly and at least they had the relatively harmless excuse that I had been thoroughly absorbed in my book. Anonymity and similar ambitions aside, I tend to be like that when reading. It used to drive my husband wild, along with a great number of other things.

Swiftly suppressing that sobering thought, I lifted my head properly and slipped the paperback back onto the table to sheepishly retrieve the tattered classic. A faint curve was showing at one corner of his mouth. It made me tell him with a foolish beam, “It seems very well written actually but I need something gentle that won’t tax my brain. At least with Jane Eyre, I know the book so well I can start at an easy bit. Even if it does feel a little like sacrilege to discard the childhood section without so much as a glance.”

I stopped. He was sitting with his forearms resting upon his paper and he was the sort of man who wore reasonably good clothes as if they didn’t matter at all. I think he belonged in this hotel rather more than I did. I also think my light reply made him feel he had just made an awkward social error. Those eyes blanked of all expression as he tried to hide it and I cringed inwardly. I cursed myself for breaking my silence so soon after all my good intentions and quickly buried my head in the book before the more alert part of my mind could find another explanation for the barely definable stiffness that had come over his posture as soon as I had begun to speak.

Some other people arrived, noisily. This was the truly fashionable contingent of the hotel’s residents. They were a Dr Alderton and wife and her younger sister followed by a capable-looking gentleman who settled with his paper at the table behind. He had arrived shortly after me the night before and he had, from what I had overheard, found something wrong with his original hotel, had almost cut short his business and made for home but then had decided to give Aberystwyth another try. I had a vague recollection of his name being Brighton. Or perhaps it was Brinnington, or something like that. I couldn’t quite remember.

“Adam Hitchen, by the way.” The man sitting at my table interrupted just as my heroine was exploring Thornfield for the first time. His manner of speaking seemed shorter now. “We’ve met before.”

“We have?” I looked up, startled all over again. Then I recalled the walker, complete with notebook and innocent binoculars, whose arrival earlier this morning on that hilltop had sent me scurrying away with my half-finished painting back down to the town. He’d seemed middle-aged in that blurry dawn light but this man wasn’t. But he certainly was the same man. When standing, he’d been reasonably tall and well-built but slim in the way men are when they have a natural enjoyment of the outdoors. Since this was consistent with the taking of lonely hilltop walks of the sort that I liked, I added easily enough, “Of course we have. You identified those little birds in the gorse for me. I’m Kate Ward; and pleased to meet you again, naturally.”

I smiled at him just long enough to imply that I meant it and then escaped into my book again. She was about to unhorse Mr Rochester, I was sure.

“On holiday?” Another interruption. It was delivered in that new oddly abrupt tone that made it seem as though he barely cared to hear the answer, but was going to ask the question anyway.

“Something like that,” I said, turning a page. There at last was the vital exchange of words between governess and master. But then manners roughly asserted themselves and I remembered that it would be better not to be rude to the same man too many times in one day. I closed my book and smiled at him, this time genuinely. “What about you?”

But the question was lost in the sudden interest of Mrs Alderton and her sister. They turned to us, or rather him, and claimed him with a flurry of excited talking. Their casual assumption that they had the right made it clear they were already on considerably better terms with this man than I.

They were both beautifully made-up. The younger sister was perhaps five years younger than my thirty-two and had lovely big doe eyes. I suspected that she knew full well the effect they had. She had also achieved the near-impossible in the form of perfect satin curls. This was something my hair would never do, which was why mine was now cropped short and left to its own devices in a woolly version of the style seen everywhere in recent years curling neatly around the base of a WREN’s cap.

The older sister, Mrs Alderton, was adhering to the new severely girdled style and she was so smart that even to a cynic it must have seemed a little odd that she had been united with a slightly moth-eaten if wealthy husband. Perhaps she thought the same because she paid the doctor about the same amount of attention as she did me; although in theory I was more relieved than otherwise to be permitted to retreat once more into the comparative sanctuary of my book.

It wasn’t a sanctuary for long. I heard the walker speak; a light response to the younger woman’s extraordinary brand of banter and I noticed that she was receiving even less than the bland sentences he had used on me. Now his replies were actually painfully flat. They made his whole person seem very dull indeed and, to be quite frank, I just couldn’t quite believe him. It made me suspect he was deliberately trying to seem insignificant here. Though it also occurred to me that perhaps he was just a little shy.

Or perhaps he simply liked to be awkward. The sister, Mary James, said something – she made an unashamed joke at her fellow guest’s expense I think; she certainly leaned in closer to deliver it – and I must have made the mistake of glancing up from my book because I suddenly found myself catching a brief and most definitely unexpected flash of wry intelligence in her victim’s eyes as he calmly countered this new attack with yet another very bland reply. They were actually grey and, disconcertingly, very alert indeed.

Mrs Alderton must have seen his glance. She certainly turned towards me with a very odd expression on her elegant face. I had already moved to gather together my things, but I felt her gaze as it took in my taste in clothes, my age and my figure before dismissing it all just as rapidly. Then it ran onto the table beside me.

“Oh. Here’s your book, Mary.”

From the distance of several feet, I felt Mary James turn like a puppet to her sister’s command. She immediately snatched up the modern paperback. She drew me helplessly away from my book again as she murmured silkily, “Thank heavens it isn’t lost after all; I’ve read it a thousand times, haven’t I, Alice? It has to be one of my all-time favourites.”

Mrs Alderton only inclined her head. Then I saw her follow it with one of those swift, calculating glances beneath lowered lashes which only ever seem necessary for married women when there is a potentially available man around; particularly if she has an unmarried sister on hand and that man should happen to be passably attractive. In Adam Hitchen’s case, he was certainly passable and I suspected that the crinkle at the corner of his eyes when he smiled very possibly qualified him for the next tier above that. Not that he was smiling now though.

“Haven’t I?” Mary’s prompt was faintly urgent. Mrs Alderton took her cue, theatrically, saying, “You really should be more careful, dear. Who knows who might try to borrow it? Not everyone has read them all you know.”

There was quite some emphasis on the ‘all’.

My gaze touched the walker’s eyes again but there was no betraying flash of character this time. They seemed in fact, if it were possible, to now be devoid of any personality whatsoever.

It was the goad I needed to lever me out of my seat and across the foyer into the mild November day.

---

The town was busier now that its residents had emerged to undertake their morning scurry to offices and shops. The thick traffic was a bizarrely confused mixture of old carts and aged horses that should probably have been retired after the war, and lorries in the crisp painted liveries of the bigger firms who had the advantage now that the basic petrol ration was being withheld from the public. There were few cars on the road. It probably explained why the vast town centre train station was absolutely crowded with people again just as it had been last night.

My destination was the Vale of Rheidol railway, a narrow gauge line tucked in a modest corner away from its larger black cousins. It was a lifeline for the remote villages dotted picturesquely along the steeply rising mountains and it gave me an odd moment when the train gave a jolting shudder and began the slow ascent.

Many years of my life had been spent in paying dutiful visits to my husband’s family in this seaside town. Then a war had been declared and he had gone away, with the result that opportunities for sightseeing of any sort had ceased for the duration. So I ought to have been thrilled now that it was peacetime and a crowded seat in a tiny carriage was gifting me a fresh glimpse of that once much loved scenery. But I wasn’t. The past minutes had been occupied by an unceasing surveillance of the platform and now I was able to only stare blankly as the valley slopes closed steadily in.

It was a fiercely controlled air of calm. I wished that I’d managed to achieve something like this yesterday during the long journey south from Lancaster. Yesterday’s hours between waking and dinner had been consumed by an exhaustion of crowded stations and carriages until the deafening rattle shook me out of logical thought. Sometime after Crewe I had convinced myself that an elderly gentleman was making notes about me and his neighbour was excessively interested in the stops along my route. All of which had, of course, later been embarrassingly – and publicly – proved false.

Today though, I was rested and defiant in the face of yet another journey. No silliness was permitted to accompany me here, not even when my neighbour smiled at me and urged me to precede him into the jostling herd of disembarking passengers at the bare levelled ground that made up the station at Devil’s Bridge.

This was a tiny place. It was situated at the narrow head of a steeply wooded gorge and spanned only by the bridge that lent the hamlet its name. A few buildings straggled along the winding road and the sole hotel peeped out over the treetops, seeming incapable of supporting the sheer volume of tourists that were descending from the train. In summer this place was darkly leafy but now, when the autumn had already struck the dead leaves from the mossy boughs, the grazing land above was like a crown above the wild sweep downhill into bleak wooded valleys.

I’d expected it to be quiet here today. Instead it was as busy as summer and I could feel the excitement growing in the crowd around me long before we swept in a sort of united disorientation of hats, handbags and raincoats around a bend lined with high metal railings towards the low parapet that signalled our first glimpse of the natural spectacle that made this place famous.

I handed my shilling to the man at the turnstile. He took my money in a greasy hand and the mechanical clanking as the turnstile’s metal arms turned was stiff and unwelcoming. But then I was through and stepping down into the sudden wilderness of dormant woodland. It was no quieter inside; it seemed as though the crowd’s chatter was magnified in here and I stood for a moment, gathering my bearings before trailing after them down the steps towards the first viewpoint.

For a while there was no view at all. The trees grew sinuously, twisted old oaks clinging to any piece of ground they could. Even leafless, the damply rusting branches still strained vigorously to reclaim the scene. They acted like a ruthless blind; for a while I could see nothing and it seemed as though the cluster of tourists might never grow bored enough to move on and leave me to take in the view in peace. But then, finally, the last of them turned away and bustled past on their own private mission to tackle the waymarked path so I could step forwards and reach out a hand to take sole possession of the cold metal barrier. Here I was at last.

It felt like a lifetime had passed since I’d first begun this journey to this place where I would mark my husband’s death.

But this was no agonised pilgrimage of the sort undertaken by a bewildered war widow. The sort where a grief-stricken wife hopes to achieve some kind of comprehension of the cruelty that stole her beloved husband’s life. This was peacetime, he was my ex-husband after our divorce thirteen months ago and he had been a stranger to me for far longer than that. This was no respectful farewell to former happiness at all.

Before me rose the bridge like a stark monument to past centuries. It held two older bridges cocooned beneath its arch. They lay one on top of the other, each bridge built at a slightly different angle to the older stonework that had gone before and each squatting over a wider gap. Somewhere far below, the fierce waters of the Mynach roared blind into the chasm; folklore claimed that the devil himself had built the first narrow crossing and today, for the first time, I could have almost believed it.

Because about eight days ago, my ex-husband had taken himself to that selfsame spot and looked down into the raging depths. And had then decided to follow the look with his body.

Whatever else had happened in the days since then and now, this part of my story at least was not a creation. The police had confirmed it. The river had been in spate; it had been swollen beyond all normal bounds by heavy rain in the hours before and there was no hope of anyone surviving that. No hope even of a decent funeral. His body had never been recovered. This river’s current was the sort that was strong enough to move rocks and trees, and a human body had been a mere speck of dirt in the stream. The only fragments the torrent had left us as proof of a man’s passing were a broken camera, a few traumatised passers-by and a ruined sock recovered from an eddy half a mile downstream.

It was insane. And worse, it was insufferably sad to have to hear polite judgements about his character, as if this could have ever had anything to do with his usual state of mind. I hadn’t received so much as a note from him in the year since our divorce but still it was incomprehensible; impossible to imagine Rhys, my stubbornly individual ex-husband, ever meaning to end it like this.