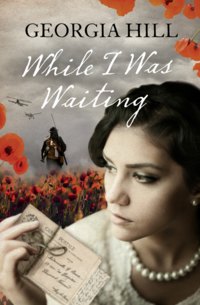

While I Was Waiting

‘Richard, you mustn’t. We’re not supposed to look at those books. It is forbidden.’ But I said it half-heartedly and followed him, avidly curious as to what lay behind the protective glass. I stood at the bottom of the steps, looking up. He opened the door and, looking behind us to check for adults, passed down to me a large leather-bound volume. I struggled over to the table with it.

Richard hopped down and pushed in front of me. Saying nothing, he proceeded to open the book at pages obviously well known to him. I stared over his shoulder until I saw what he was laughing at. Then I caught my breath.

The images seemed to me, at that time, grotesque. They were engravings of human forms entwined in unspeakable acts. The men and women seemed intent on doing violence to one another. The men, with bared teeth, fastened on throats thrown back. Hands were clutching parts of the anatomy I did not – had not – known exist.

Richard saw my reaction of horrified fascination and sniggered. ‘This one is the best.’ He pointed to a picture of a man mounting a woman in the way I had seen the bull do to a cow at the Parkers’ farm, until Nanny had pulled me away. She had responded to questions with tight-lipped silence.

‘What do you think?’ Richard asked, watching my face intently. ‘If you marry Ed, that is what he will do to you on your wedding night.’

I backed away, shaking my head violently, clutching my heaving stomach. No man was ever to do to me what I had seen in those disgusting pictures. But even then, part of me was acknowledging the truth of what was being shown to me. Forgotten images were remembered: Elsie the kitchen maid and Robert the under-gardener looking red-faced and untidy when I walked in on them in the empty stables, Edward being teased over Flora Parker until he blushed crimson and hurried from the room, Nanny hushing my questions about the bull.

Information was sliding greasily into place and locking together to make a truth.

‘No …’ I looked at Richard.

He grinned back, ‘Oh, yes. And then your stomach will grow and grow and one day a baby will come out. The chaps at school told me.’ He spoke conversationally and completely without malice.

My eyes filled with tears and I felt sandwiches and cake threatening to return.

‘I say, Hetty, old girl. I didn’t mean to upset you.’ He made a move towards me, concern on his face.

I turned and ran from the library, the scent of lavender polish sticking in my throat.

‘Wait Hetty! Hetty I’m sorry! I just thought it would be a wheeze.’

I found myself in the summer house, the old refuge. It was intensely cold and I could see my breath making clouds in the frigid air. I wrapped my arms around myself and began to rock to and fro.

What was the connection between what had been happening to me and those pictures? At some deep level the links were forcing themselves to be made; there had to be a connection. Was that what it meant to be a woman? If so, I wanted no more of this adulthood. I yearned to be a child. I yearned for my long-lost mother. Tears began to drip down my face and I hid it in my pinafore.

After a time, and when my tears had dried, I heard a sound outside. The sound of footsteps. I froze, willing them to go away.

‘Henrietta – Hetty – are you in there?’

It was Edward. Of all people, I could face him the least.

I stayed still, my face hidden in my skirts, like an animal gone to ground.

‘Hetty, there you are! Richard said you had been taken ill.’ A relieved-sounding Edward came into the summer house. ‘We’ve all been looking for you. Come back to the house, you’ll catch your death of cold out here.’ He sat down on the crumbling bench beside me. ‘Hetty, are you unwell?’

I remained silent, but my shoulders began to heave again. I felt a tentative hand on my arm and shrank away.

I heard Edward sigh. ‘Look, if you won’t come back into the house, shall I fetch the aunts, or your father? Only,’ he paused and then went miserably on, ‘Richard said something about a book? Some pictures? He said they frightened you? If it is what I think it is, I think it better the aunts don’t know.’

I heard no little anger in his voice and raised my wretchedly tear-stained face to look at him for the first time. ‘I saw –’ and then had to stop.

Edward’s face tightened with anger and he nodded. ‘I thought as much. When I get my hands on that little so-and-so I’ll thrash him until he can’t sit down. The little –’ he bit off what he was about to say with another look at me.

I found my voice at last. ‘Richard didn’t mean to upset me. He thought it was a joke.’ I wiped my damp face with my pinafore and shivered.

‘When will that boy ever learn to think before he acts?’ Edward said it softly. He shrugged off his jacket and laid it gently over my shoulders. It was heavy and made of rough tweed, but warm from his body. He cleared his throat. ‘Erm, so, what do you know?’

I looked at him in panic. He blushed and became very busy lighting a cigarette.

‘You know, it really ought to be your father or Nanny or Aunt Hester talking to you.’

I shook my head and hid it back in my skirts.

Edward sighed again, even more loudly. ‘But, as it seems to be me in the wrong place at the wrong time, perhaps I ought to tell you.’

I sneaked a look at him. He was concentrating fiercely on his cigarette. His nose turning pink with cold.

‘I should quite like it to be you.’ I said in a tiny voice, hardly believing my own daring.

He coughed slightly and put a hand through his hair, making it stand up in comic fashion. ‘Oh Lord,’ he groaned.

‘Please tell me Edward,’ I said, ‘I think it might be better to know it all than some of it. It might make it seem less frightening.’

Edward shook his head.

‘Father always says if one wants to know something one should ask questions.’ I straightened my back and took comfort that Edward’s discomfort seemed even greater than mine.

He gave a little nod, as if a decision had been made and smiled at me through the blue tobacco smoke. ‘And your father is a great scientist, a very learned man. Well, shall we be scientists? Shall you begin with a question, little Hetty?’

And so I did. And Edward, in halting fashion and with many blushes, told me of what to expect on my wedding night. He told me the simple biological facts at first, but then, as he elaborated, I became more and more fascinated, my natural curiosity taking over.

‘But it looked so, so violent in those pictures. As if they were killing one another, not loving one another!’ I thought back to the images with this new information whirling around my brain. It was at once repellent and fascinating.

Edward shifted on the bench and there was a long pause. ‘Well, I understand it can take one like that.’ He looked at the gathering darkness outside. ‘But remember, Hetty, it is for people who love one another very much. And sometimes love takes many forms, sometimes it is passionate. And that passion can seem like violence.’

I looked at him, sitting in the cold, shivering openly and being so brave for my sake. I wondered, perhaps, if he were thinking of the beautiful Flora Parker. ‘Have you, have you ever –’ I began.

‘Good Lord, Hetty, the questions you do ask.’ He lit another cigarette with trembling fingers and made much of flicking away the match. I had my answer. It satisfied me.

‘Richard says I am to marry you and you will take my money to rebuild the house.’

Edward turned, a startled look on his homely face. ‘Richard is a –.’ Here he said a filthy word and the oath came out violently. He sucked deeply on his cigarette and there was a long pause. ‘Sorry, Hetty. Forgot myself. You know our family has little money.’ He gazed around at the shabby summer house, full of hints of lost glory. ‘And it would take a great fortune to restore Delamere. More than you have, I am sure.’ He smiled. ‘If you would like to marry me, then so be it. But that is for many years from now. And we have all the time in the world to decide. Come along, we must go back to the house, they will be wondering where we are and it is bitter in here!’

He held out his hand to me and I stared up at his face in a daze. I had hardly known Edward before today. This strange little interlude in the summer house had convinced me of one thing: he might not be as much devilish fun as Richard, but he was an infinitely kinder person.

I took his hand, not sure if I had just received my very first proposal – and even less sure how I felt about it.

Chapter 8

April 2000, Clematis Cottage, Stoke St Mary, Herefordshire

It was the first day the Llewellyns were expected to start work and Rachel sat at her drawing board, too wound up to do anything other than stare at the view.

She felt half resentful, half relieved. Although pleased that work was to begin on the house, she was reluctant to give up sole possession of it. Knowing it was pointless to paint or do any more work until Mike and Gabe had finished, she had limited her refurbishment to the sitting room.

Reluctantly.

The room had become ever more her refuge. She’d had to grit her teeth not to put the rest of the house in the same order. However, bringing a temporary halt to any DIY had freed up time for her to sit at the window, gaze enraptured at the view and begin, at last, some serious drawing work.

Until this morning.

She expected her builders any minute and it made her too on edge to even pick up a pencil. She was worried about so many things: how she was to get any work done with muddy-shod builders stomping through the house, the noise, the mess, most of all the disorder. Not to mention the expense.

She’d got used to the tranquillity in the house. She liked the solitude, the freedom to talk to the walls if she chose, and to ignore anybody she didn’t wish to talk to. She’d even cut back on phone calls to Tim and Jyoti. Tim was too loud, too demanding, somehow, for her current mood and Jyoti had seemed preoccupied and uncommunicative.

Looking at the clock for the fifteenth time that morning Rachel began to draw randomly. Sometimes the very act of having a pencil in her hand, making marks, could calm her, lead her into doing something more useful or productive.

She braced herself, pencil poised in mid-air. She could hear a vehicle advancing up the track. She watched as Gabe and his father unpacked an alarming amount of tools and materials. Her knuckles clenched to white on the drawing board. It felt like another Llewellyn invasion. Behind her, the room seemed to prickle and a wave of apprehension rippled around her. The house seemed to disapprove of the interruption too. Rachel liked a place for everything and everything in its place. Several builders roaming around – and their accompanying mess; it would be enough to drive her insane. God, she was turning into her mother.

Gabe spotted her at the window, said something to Mike and came along the path to the house. He rapped on the front door.

Rachel, taking a deep breath, and with a feeling that life was never going to be quite the same again, rose to open it.

‘Hi Rachel,’ Gabe said cheerfully. ‘We’re just unloading the stuff. Dad’s got to go on to the Halliday job, so I’ll wait here to supervise the scaffolding lads. There might be a bit of noise, bit of to-ing and fro-ing today, but after that we shouldn’t have to disturb you too much until the radiators arrive. You won’t know I’m here, I reckon.’

‘Oh,’ said Rachel, taken aback at how easy he made it sound. ‘Fine. Shall I, erm, put the kettle on?’

Gabe shrugged. ‘I’ve got a flask with me, so don’t worry.’

‘Right,’ said Rachel, now thoroughly deflated but feeling some of her tension easing. ‘I’ll just go back to – I’ll get on with some work, then.’ She was disappointed she wouldn’t be seeing more of him.

‘You do that. I’ll knock if I need anything, but apart from that, you won’t see me.’

After that anti-climactic start, it was exactly as Gabe said. The scaffolders were a noisy, cheerfully coarse bunch, who swore freely but who were only there for a couple of hours on the first day. Rachel guessed they’d been chivvied along by Gabe and her gratitude and liking for the man increased. After the scaffolders disappeared, apart from the odd thump and the sense that there was someone else around, it was relatively quiet, even peaceful.

The days settled into a rhythm. Gabe arrived early in the morning, sometimes with Mike but more often on his own and, without ceremony, got on with the job. After waving to Rachel as she sat at her desk in the window, he disappeared around the back of the house. Unless she made an effort to do so, Rachel hardly saw him.

On lunchtime of the third day, Rachel’s curiosity got the better of her and she went to find Gabe to ask about progress.

Her beautiful red-brick cottage had been encased, almost in its entirety, in ugly scaffolding. She found Gabe perched halfway up the back of the house re-pointing the wall. She peered up, shielding her eyes from the glare of the sun. He was dressed in his customary jeans and scruffy t-shirt. From her position on the ground, she couldn’t help but admire the view of his beautifully shaped rear and long, well-muscled thighs.

‘Hi,’ he said, without turning from his work. ‘Surprised the damp hasn’t penetrated that back wall more. This mortar’s shot to bits.’

‘Would you – would you like a tea, or coffee or something?’ Rachel said hesitantly. ‘I was just going to make myself one.’

At this, Gabe did turn round. He looked down at her and blew his hair out of his eyes. ‘That would be great. Could do with a break. This job gets really tedious after a while.’

‘I’ll be on the front step, then.’

‘Sweet. I’ll be there in five.’ He gave her a charming grin, which made Rachel’s heart skip to a girlish beat.

And so, a pattern for the days was set. Most lunchtimes Rachel and Gabe met on the front step of the old house, just as they had on that first evening, and sat, drinking tea. Rachel began making sandwiches too, which Gabe ate like a man starving. She thought it might be awkward, but strangely it wasn’t. It was companionable, even. He was the exact opposite of someone she expected to get along with, but even when they had nothing to say to one another, the silence was comfortable. It was all very odd.

Once or twice she’d shared an ongoing piece of art and, again, he’d shown that surprising sensitivity.

‘The views from here must be inspiring. Maybe you could do something based on a landscape,’ he suggested. It echoed an earlier idea she’d had.

‘The views are stunning and they are inspiring,’ she admitted. Then she’d turned to him and laughed. ‘They’re also really, really distracting. I had no idea watching a flock of sheep chase a farmer on his quad bike could be quite so fascinating.’

Gabe had grinned and told her it was Terry Garth. He’d shaken his head. ‘He’s completely addicted to his new toy, but claims it speeds up feeding time.’

‘When are you coming down The Plough?’ he asked one day, having demolished the doorstop cheese sandwiches Rachel had provided. ‘There’s a good crowd on a Friday night.’ He turned his face up to the sun with evident pleasure. ‘Oh boy, we’re lucky with this weather. Makes the job so much easier. We can get on far more quickly.’

Rachel could feel the heat radiate from Gabe. Could smell him; soap and something expensive. His smooth skin seemed even browner today. She looked away, anxious not to be caught staring. He disconcerted her. Something about his animal presence attracted her deeply. But it was that very quality which disturbed her too. None of the men she’d known had that almost primeval, base quality that emanated from Gabe. And her first impression had been right. He was resolutely straightforward and honest. It was very refreshing.

With difficulty, she focused on his question. Part of her knew she ought to try out the local pub; it would be a good way to get to know some of her new neighbours. ‘Oh, maybe sometime,’ she said, deliberately vague. ‘Thank you for the invitation, though.’

Gabe was not to be deterred. ‘I’m usually in there. I’ll introduce you to one or two people, if you like. Kev can be a pain, but Paul and Dawn are okay and Stan Penry’s started to come in again now. He’s a character, lovely bloke, though.’ He twisted around and pulled a newspaper out of his back pocket.

She put him off, saying she’d think about it. It wasn’t that she wanted to seem aloof, but she didn’t think she felt quite ready to go into the village local on her own, however friendly the crowd and with the promise of Gabe’s presence. Or maybe it was the possibility of Gabe’s presence that made her so wary.

Rachel risked a glance at him, as he bent over the battered copy of his tabloid. He was a revelation. His sensitivity was all-encompassing. If he sensed she was working, he left her completely alone. It still surprised her how easy it was to have him around. The solitude she usually craved when working didn’t seem as important now. In fact, she was getting more done by having him there. She found having Gabe in the background easy company and relaxing. In one way. In another, she found him very disturbing indeed. The thought made her smile.

Gabe snorted at something he was reading, threw down the paper and picked up Rachel’s copy of the Hereford Times. Turning to the back, he was instantly engrossed in the sports pages.

Without really knowing why, Rachel found herself wanting to make contact with him. Wanted him to talk to her.

‘I’ve been reading through some of the contents of that tin you found,’ she said, ‘you know, the one in the attic? Hetty, Mrs Lewis, that is, once lived in a big house in Upper Tadshell. It was called Delamere House. That’s not far from here is it?’

Gabe glanced up.

‘And she had two relatives. Well, very distant relatives. And two aunts, one called Hester and –’

‘What?’ Gabe looked at her, patently not having heard a word. ‘Sorry, just checking on how Hereford got on.’

‘Hereford?’ asked Rachel blankly.

‘United. They were away on Saturday. Won, though, three nil.’

‘Oh football.’ Football had never featured in Rachel’s world. Before now.

Gabe misunderstood her tone, thinking she was being dismissive. ‘Yes, football,’ he said, amused. Some of us lesser mortals like to watch it.’

Rachel had the feeling she was being teased.

‘Aren’t you interested? In Mrs Lewis I mean. I thought you might be, seeing as you were the one who found the tin.’ Having read the next few pages of Hetty’s journal on her long train journey to London, Rachel was bursting to discuss it with someone. Jyoti was again being peculiarly distant and Tim was in the middle of another break-up with boyfriend Justin. That only left Gabe.

‘Sorry. Just had to check up on how the boys were doing.’ Gabe folded the newspaper away, leaned back against the front door and looked at Rachel from underneath long, dark lashes. ‘I’m all yours now.’

‘Erm, I, erm –.’ There was suddenly something about him that made her lose all interest in Hetty. Her throat constricted and Rachel couldn’t have spoken had her life depended on it.

A silence built between them, unusual in that it was awkward.

‘Could look at this all day and still see something different,’ Gabe said. Then, finally taking pity on her, he looked away. He smiled and nodded at the prospect before them. ‘This view, I mean.’

‘I know, I still think it’s gorgeous. It’s why I bought the cottage,’ Rachel said in a rush, feeling heat flush her cheeks. For a minute, she wasn’t sure just what Gabe was referring to.

He laughed. ‘Would you have changed your mind if you’d known how much work there was to do?’

She gave him a quick sideways glance. ‘You know, I’m not sure I would.’

‘So, you’re settling in? No regrets, then?’

Rachel thought about what she had left. Rows of once-proud houses converted into flats, their front gardens concreted over, on which to shove cars, no sense of community, alarms sounding out in the night, the scream of sirens wailing past. The shallow men she’d always seemed to attract. ‘Not one,’ she said firmly and meant it. And then pulled a face. ‘Although it’s a shock having to go and get your papers from the shop. There’s something so nice about having them put through the letter box on a Sunday morning.’

‘I know, Dad’s always moaning on about it. Lucky we’ve still got a shop, though, the one in Stoke Bliss closed down. Reckon ours will at some point, when Rita retires.’

‘Stoke Bliss,’ murmured Rachel. Upper Tadshell, Nether Tedbury, Stoke St Mary.’ She rolled the words around her tongue, enjoying the sounds. She loved the place names in the area. ‘Why doesn’t she do a delivery service?’

Gabe shrugged. ‘Says it’s too scattered a population to do it. Would cost her too much. You can see her point, though. It’d take ages. Mind, I reckon it’s because she can’t get any paper boys. No one’ll work for her.’ He pulled a face. ‘Not the easiest woman in the world.’

Rachel laughed. Having come across Rita, who ran the shop and post office, she knew exactly what Gabe meant. She lifted her hair from her neck in an effort to cool down, her face still felt hot. ‘In London, I used to pick up the early editions on a Saturday night on the way home from a night out. Then they’d be there, ready to read on Sunday morning. With good coffee and a pastry making crumbs in the bed.’ Still holding her hair aloft she nodded her head from side to side to ease out the kinks from a morning at the drawing board.

As an unconscious gesture, it gave off a wholly and peculiarly erotic charge.

Gabe couldn’t look away. Didn’t want to. A picture was forming in his head. Rachel: her long, dark hair tousled, wearing a silk robe – no, better still, a silk negligée, Sunday papers scattered as they abandoned them. He shut his mind off and concentrated on the view, watching as a tractor on the Garths’ farm ploughed an immaculate furrow. Did she have a clue about what she was doing to him? To distract himself he asked: ‘So what’s this about Hetty, then?’

‘You were listening!’ Rachel, delighted that she had an audience, gave Gabe a beatific smile. She began to tell him all about Hetty’s traumatic experience at Christmas. ‘So, I can only assume Richard showed Hetty some kind of Victorian –’. She stopped, embarrassed.

‘Porn?’ Gabe questioned and guffawed. ‘Now that’d be worth looking at. Don’t suppose there’s any in that tin of yours?’

‘No laughing matter,’ Rachel said, trying not to sound like her mother, ‘it must have come as a hell of a shock to poor Hetty. She wouldn’t have known anything.’

‘What, nothing at all?’ Gabe was scandalised.

‘Nothing. I remember my grandmother telling me she knew absolutely nothing until the wedding night. And that was only fifty or so years ago.’ Rachel felt the treacherous heat rise in her face again. She wasn’t sure it was quite the thing to talk about sex with Gabe.

‘Jeez,’ Gabe said. ‘Makes you wonder how folks managed. It’s hard enough the first time when you know what you’re supposed to do!’

Rachel studied him. Despite what he’d said, she imagined Gabe having no problems in that department. He seemed very at home in his skin. ‘Erm, yes. Edward must have been an unusual man to have that conversation with her. I just can’t picture a repressed Edwardian telling a young girl the facts of life like that.’

Gabe scratched his head with the pencil that seemed to be permanently stored behind his ear. ‘Don’t know how repressed they were. You say this Edward was some sort of scientist?’

Rachel nodded. ‘He went off to university, apparently.’

‘Well, maybe he took a scientific approach. Just told her the bare facts, like. Probably the best way. Better than being all coy.’

Rachel nodded. ‘Possibly.’

‘Kind thing to do, though. Think I like Edward. So, do you reckon she’d been hauled in to marry him, then?’