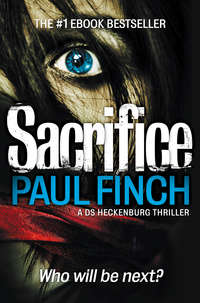

Sacrifice

‘Who do you think?’ Heck said.

Palliser smiled fondly. ‘Taught her everything she knows.’

‘I always knew we had to thank you for something.’

‘I’m glad you could come, pal.’

Heck glanced around at him. ‘No one had to drag us here, Des. You’ll be missed too.’

‘I want you to do something for me.’

‘Name it.’

‘Be careful, okay?’ Palliser regarded him gravely. His face was a nest of wrinkles, his teeth gnarly and yellowed by decades of smoking, yet all of this served to give him character. ‘No more go-it-alone heroics like we saw during the Nice Guys enquiry. No job’s worth putting your life on the line for.’

Heck smiled. ‘It’s not something I plan to make a habit of.’

‘And that M1 Maniac thing was almost as bad. You got some kind of death-wish?’

‘Just the way the cards fell, Des.’

‘Doesn’t matter.’ Palliser put a hand on his shoulder. ‘Heck, you’ve got a good boss in Gemma. Make use of that. Try and forget you and her once had a thing going. Unless of course, well …’ he almost sounded hopeful, ‘unless you feel like going there again?’

Heck glanced towards Claire, who, though she was besieged by shouting, guffawing coppers, was also laughing. Gary Quinnell made some jibe, but she responded sharply and they fell about again.

‘I don’t think so,’ Heck said slowly.

Palliser followed his gaze. ‘Something more interesting on the horizon?’

‘Who’s to say?’

‘Well … if it gives you a reason to go home at night, all to the good.’

‘Who are we kidding, Des? She’s probably got a boyfriend with a Ferrari.’

‘Just remember what I said, eh? Do what you do, Heck … you’re bloody good at it. But be sensible and be safe.’

Heck nodded, surprised by the depth of feeling in his colleague’s voice.

‘Anyway, what’re you having?’ Palliser lurched away to the bar.

‘Bitter please,’ Heck said to his retreating back. ‘Pint of.’

Gemma strode up. She looked as cool and unruffled as ever, despite the heat and noise. She glanced after Palliser. ‘He sorry to be going?’

‘Thinks SCU will fall apart without him,’ Heck replied.

‘The perceptiveness of old age.’

Heck nodded towards Claire. ‘Our new recruit looks comfy already.’

‘Good.’ Gemma sipped her mineral water. ‘Because there’s no point us handling her with kid gloves. This’ll be a testing job.’

‘Presumably she’s well qualified for it?’

‘Worked for a major financial house in the City and at least two government departments.’

‘When does she start?’

‘Tomorrow morning.’

‘That soon?’

‘She might as well get her feet under the table while things seem to be fairly quiet.’

Heck pondered that, wondering if they were challenging fate. He wasn’t superstitious, but one thing he’d learned during his seventeen years as a police officer was that you didn’t make any decisions based on an assumption that nothing tumultuously crap was about to happen. Because, almost invariably, it was.

Chapter 8

‘Look … whatever happened to you in your past, whatever it is that’s making you do this, I beg you to reconsider.’

Kate wasn’t sure how much her abductor could hear. He hadn’t actually gagged her, so, although she was swathed in this dirty old blanket which stank of sweat and stale urine, there was nothing to prevent her trying to project words. No doubt they’d be muffled, while the ongoing rumble of the engine and the vibration of the tyres on the road might blot them out altogether. But given that she was still bound and that no matter how much she wriggled, she remained tightly trussed, she had no option but to keep trying.

‘Please listen to me,’ she begged. It had been two hours at least, and at no stage had she received a single reply. ‘I understand that someone was once cruel to you. Maybe they tortured you – over months, perhaps years. But what you’re doing now is in no way going to make up for that. You won’t be getting even with them, you won’t be punishing them. You’ll just be hurting an ordinary person who bears you no ill will, doing exactly the same thing as was done to you …’

She was more terrified than she’d ever been in her life. The revolting stench inside the blanket would only get worse as her own sweat of fear mingled with it; it was highly possible she’d add her own urine to it, maybe her own vomit, and the temperature didn’t help. The heater in the car had activated some time ago and now was at its stultifying worst, but she couldn’t afford to let it fog her reason – not yet. The only weapon available to her was her intellect – so she had to continue with this, trying to appeal to his better nature, if he had one.

It was appalling to think that anyone could be reduced to such a state that they’d do this sort of thing. She’d heard stories of course: about street people who’d had petrol poured on them and been set alight while they were sleeping rough, about stabbings and clubbings, about their being made to fight each other with chains and bottles while someone filmed it. Yet none of these abhorrent things had seemed real – not even to Kate, who worked with the victims – until now, when it was apparently happening to her.

‘Listen … please!’ It took an immense effort of will to reduce the quake in her voice, to make her sound less like a frightened little girl. ‘Please … this hatred you’re demonstrating. It’s not a natural state for a human being to exist in. Don’t you see that? Animals don’t live that way, not even animals that have been scarred by illness or injury. They just accept it and get on with life. Don’t let the person who abused you win by watching you become a mirror-image of him. Remember what it was like when …’

She’d wanted to talk about the days when he himself was a young child, but no … that could be a horrendous mistake. Some of these poor creatures’ earliest memories comprised nothing but pain.

‘Remember your humanity. Try to think how you like to be treated. I know that’s something that was denied to you. But try to picture yourself on a normal morning, setting out with no intention of doing harm to anyone, just hoping to get through the day in a simple, dignified manner. Isn’t that how you feel most of the time? There’s no pleasure to be found in what you’re doing now. You understand that, I know you do.’

She halted, not just to get her breath – which was increasingly difficult in the sweltering confines of the blanket, but to listen in case there was any response from whoever was driving. There wasn’t. But if nothing else he had to be listening. He hadn’t put the radio on to drown her out.

‘I’m making one last appeal to you,’ Kate said. ‘Whatever you think you’ll gain from this, you’re wrong. I know that sounds arrogant and presumptuous of me. But I honestly know about this. I work every day with people who have suffered the most dreadful misfortune. Most of them are deeply miserable and deeply angry. But in almost all cases – when you sit down and counsel them, try to get through to the person who was there before – they are ordinary men and women, and they realise that giving in to their baser instincts will achieve nothing …’

Her words petered out as she realised the vehicle was jolting and bouncing, as if traversing rough ground. The terror of this took her breath away. She imagined wasteland somewhere, far from prying eyes.

There was a change of tone from the engine. The Fiesta was slowing down.

With a clunk, the gearstick shifted, then the handbrake was applied. When the engine was switched off, the silence was ear-pummelling. Despite the kiln-like heat, the sweat coating Kate’s body was ice-cold. A seatbelt was unfastened; a car door was flung open. Horrifyingly, there was no sound of night-traffic from beyond. Wherever he’d brought her to, it was far, far from civilisation.

Kate’s whimpers became helpless wails as a door was opened next to her head, and brute hands yanked the straps aside, grabbed her and threw her over a brawny shoulder. The effect of this was to nauseate her, a sensation that grew worse as she was carried through the darkness. Heavy feet crunched what sounded like soil and leaf debris, and then clumped on hollow wood, the impacts of which began to echo – she was inside a building. Different smells assailed her: sawdust, fresh paint. When she was dumped onto the floor, she felt rugged planking, nail-heads. Old hinges squealed and a foul smell arose. Kate felt a new sense of paralysing horror.

A trapdoor had been opened alongside her.

Those hands gripped her again and lifted her. Before they dropped her down into the void, a hoarse voice whispered in her ear: ‘You have a good heart and an eloquent tongue. That makes you more than worthy.’

Chapter 9

‘Morning!’ came a bright, cheery voice.

Heck, who wasn’t suffering from a hangover, but who was slightly muzzy-headed, glanced up from his desk. Claire Moody was standing in the doorway to the Detectives’ Office, or DO, as they called it. ‘Oh, erm … hello,’ he said awkwardly.

She stripped off her overcoat as she glanced at the empty desks and unmanned computers. It was just past seven in the morning. Heck was the only one in, but perhaps Claire hadn’t expected to find anyone. ‘You’re bright and early,’ she said.

‘Well … so are you.’

‘I didn’t have anything to celebrate last night.’

‘None of us did, if only we’d realised it. Des is a good guy. Look, don’t stand out there on ceremony, come in.’

Claire entered, coat folded over her arm. ‘Des obviously has a lot of friends.’

‘Yeah, got a bit crazy in there, didn’t it? Your office up and running now?’

‘Hardly … I don’t know where anything is yet.’

As far as Heck was aware, a room had been set aside for the new Media Management suite just along the main corridor, and though a carpentry team and then the techie guys had been in it during the last few days, he hadn’t got the impression it was anywhere near ready for use. But he remembered what Gemma had said about easing Claire in as quickly as possible.

He stood up. ‘Erm … I can give you the tour, if you’d like.’

‘No please, it’s okay. Don’t let me interrupt you. I think your work’s a bit more important than mine.’

In broad daylight, viewed through the eyes of sobriety, Claire was even more attractive than he’d first realised. She wasn’t just pretty, she was gracious, well-spoken, innately pleasant … almost genteel. He had a worrying feeling that what Bob Hunter had said might turn out to be true, and that Claire would prove to be too nice for this environment.

‘If nothing else, I can offer you a brew,’ he said. ‘I’m guessing you haven’t got your own tea-making stuff yet?’

‘I hadn’t even thought about it. Thanks, I’d love one.’

He produced a key, unlocked a cupboard near his desk, and took a kettle out, along with a big bottle of water, two mugs, a jar of teabags, a cup of sugar and a sachet of powdered milk. ‘Here’s a tip. Keep this kind of gear secured, because round here it’ll walk … usually upstairs to Organised Crime.’

‘You can’t trust police officers, eh?’

‘Definitely not.’ He filled the kettle and plugged it in. ‘Don’t be scared of us, though; we don’t really bite. Speaking of which, the boss will be in soon. I suppose she’ll brief you on everything you need to know.’

‘She’s fire and brimstone, isn’t she?’

‘See … you know her already.’

Claire glanced around again at the sprawling, open-plan office. Despite its size, the DO bore the usual police hallmarks of organised chaos. There might be nobody else in at present, but desks were strewn with documents, in-trays overloaded, paperwork and photographs hanging in disorderly wads, not just from noticeboards but from those few patches of wall that weren’t already covered with maps, timetables and flow-charts.

‘I was a bit unsure I was doing the right thing when I actually got the job,’ Claire said. ‘I mean, I’ve been in PR all my working life, but this is something totally new.’

‘It’ll probably amount to the same thing you had at the Department of Utilities.’

She looked surprised. ‘You know I was at Utilities?’

‘Not to mention the Ministry for Cultural Affairs,’ he added. ‘Don’t worry … nothing stays quiet round here for long.’

‘Obviously not.’

‘Just do what you did there. Fob the public off with any old crap.’

She gazed at him, uncertain whether to take him seriously.

‘Do that and you’ll fit right in,’ he said mischievously.

‘You’re Detective Sergeant Heckenburg, aren’t you?’

‘Call me “Heck”. How many sugars, by the way?’

‘None please, just milk. If I remember, Superintendent Piper said I should only believe five per cent of anything you told me.’

Heck handed her a steaming mug. ‘That was a bit mean of her. Ten per cent at least. While you’re still a newbie.’

She looked thoughtful as she sipped. ‘Seriously, do we often get crimes where … well, where we have to be economical with the truth?’

‘Seriously? … I couldn’t comment. All I do is investigate them.’

‘Superintendent Piper seems to think you’re very good at that.’

‘Even though I’m a bare-faced liar?’

‘She thinks you’re too opinionated as well. And sometimes pig-headed, and that you try to do everything yourself because you think – wrongly – that you know better than anyone else in the whole police force.’

‘You two had a chat about me, eh?’ Heck feigned suspicion, but inwardly was pleased. He’d just revealed to Claire that he’d researched her, and she was now revealing that she’d researched him. Touché.

‘She also thinks that you enjoy much more leeway in the job than is good for you, or her,’ Claire added. ‘And that you don’t know how lucky you are to have her for a boss.’

He arched an eyebrow. ‘Are you pulling my leg?’

‘She’s still glad you work for her though.’

‘That proves it. If you’re not pulling my leg, she was definitely pulling yours.’

Claire chuckled. ‘So what’s on the agenda for today?’

He indicated the documents and photos on his desk. ‘Well, for me … these.’

Claire glanced down – and almost dropped her tea. ‘Oh my God!’ She promptly turned a milky shade of grey. ‘Are these … real crime scenes?’

Heck eyed her curiously. ‘Well, we don’t deal in movie-stills.’

The first of the two photos displayed a youngish man, possibly in his late twenties, stripped to his underpants and hanging by the hands from a tree branch. His limbs and torso were black and purple as though from a savage and sustained beating – but perhaps the most disturbing thing was his face, which had been painted with clown make-up: a white base, rouged cheeks, a red nose, black cream liner around his glazed, bloodshot eyes. The second picture showed a naked woman lying in a bath; she too had been brutalised, her body battered beyond belief, splintered bones protruding through the pulped, shredded flesh – and she too was wearing clown make-up, the lips green, the eyes and mouth thickly outlined in white, forming a ghoulish smile.

Claire had physically backed away; it had been an involuntary motion, but there was more to it than a nervous flinch.

‘You alright?’ Heck asked.

She nodded, her eyes riveted on the photographic horrors. ‘I will be, yeah. Sorry … that’s the first time I’ve ever seen a real murder.’

‘That’s something you’re going to have to get used to, I’m afraid.’

‘Yes, yes … I realise that, of course. Oh my God, these are awful …’

Heck flipped the photos into a buff folder. ‘Probably a bit much for your first morning.’

‘Probably, but …’ She seemed to steel herself, planting her tea on the desk. ‘As you say, it’s something I’ve got to deal with. So, why don’t you tell me about it?’

‘This case, you mean?’

She nodded.

He regarded her warily. ‘If you’re sure?’

She nodded again, determinedly.

‘Okay …’ He sat down and reopened the folder. ‘The murders of this man and woman occurred last month, about two weeks apart – in Gillingham and Maidstone respectively. The Murder Squad in Kent sent them along for our assessment as a matter of course.’ He glanced up at her. Claire was doing her damnedest to focus on the two images and at the same time maintain a cool, professional demeanour. ‘They obviously look similar,’ Heck said. ‘But my impression is that they aren’t connected.’

‘They aren’t?’

‘Given his own criminal record, I suspect the male was the victim of a gangland vendetta. The brutality is quite excessive, so it may have been a punishment.’

‘They were making an example, you mean?’

‘Correct. My gut feeling about the woman is that she died during a domestic incident. The perp is probably her husband.’

Claire looked at him askance. ‘Are you serious?’

Heck shrugged. ‘He reads about the first homicide in the papers, and he thinks it’s so wild and whacky that it can only be a matter of time before a lunatic capable of doing that will strike again. So he decides here’s his chance to knock off his nagging missus and make it look like someone else. Of course, he doesn’t realise that the first killing is down to organised crime … which illustrates the advantage we gain from only telling the press as much as we have to.’

‘But how can you be sure this is domestic?’

‘I’m not absolutely sure. But my advice to the Murder Squad in Kent will be to look a bit closer to home first, and the other facts support this. This woman was murdered in her own bathtub early evening – to be specific between seven-thirty and eight-fifteen. The timing of that incident alone would make it unusual for a home-invasion by a stranger. In addition, the window of opportunity is too small. The husband, who found her, would have us believe that he’d driven off to the local golf club to pay his annual subs. He’d also have us believe that in this brief time, some headcase happened to walk up to an ordinary suburban home, ascertained that the female occupant was alone, forced entry, did the dirty deed, painted a clown face on her, and then vanished without anyone seeing or hearing a thing.’

‘It seems unlikely, but could that be what happened?’

‘We don’t close the door on any possibility – the perp may have scoped the house out beforehand and lain in wait. But the husband didn’t leave the premises as part of a regular routine. So that makes it improbable. On top of all that, the first victim was a male in his late twenties, the second a female in her early forties. There was no sexual assault in either case. Okay, it could be some complete madman who just gets off on drawing clown faces. But that’s not the sort of guy you’d expect to have kept his light under a bushel up till now.’

‘So … what happens next?’

Heck sat back. ‘I send it to Gemma with my report. I don’t recommend that we get involved because I don’t see any need. Our main responsibility is to identify patterns, series and clusters that may indicate a repeat-offender, and then respond accordingly.’

‘What if Gemma disagrees with you on this?’

‘If she disagrees, some of us – almost certainly me, as I copped for the job in the first place – will be off to Kent, which would be great because that’d take me out of the office. But I can tell you now she won’t. Most likely she’ll just send our official observations.’

Claire glanced further along the desk. There was another pile of similar folders awaiting his attention. Other desks in the room were equally weighed down. ‘Are all these files the same kind of thing?’

‘We get copied in on a lot of stuff,’ Heck said. ‘But most of it is what we call “slush”.’

‘Slush?’

‘Not relevant to our remit. Various types of crimes are automatically sent for our assessment. All stranger-murders of children, for example. All murders of prostitutes. All murders of runaways. All murders committed during burglary or rape. All murders involving exceptional violence, sadism or depravity. All murders where there are ritual or theatrical elements. All murders where there’s evidence of bizarre post-death behaviour – mutilation, dismemberment, necrophilia. All murders where the perpetrator has apparently tried to contact the police or press … left clues, cryptic messages, that kind of thing. All murders which may not satisfy any of these criteria but where there is reasonable suspicion that it’s part of a series. And basically any murder at all that we request to look at. No police force in England and Wales has the right to refuse us.’

Claire glanced around the room again. In another corner, two more crime scene blow-ups were mounted on a noticeboard amid masses of scribbled notations. One was a close-up glossy of a middle-aged black woman. She looked to have been propped against a wall in a house or flat. Her grin stretched from ear to ear – literally, because someone had slashed her cheeks with a razor blade and had fixed a stick vertically in her mouth. The other had been taken in a bedroom, which looked like it had been wrecked by a hurricane. The bed occupied the centre of the image. A figure lay in it hidden by a sheet, though so much blood had soaked through this that a clear outline of the body was visible. On the wall above it, bloody handwriting proclaimed: ‘Hey Mum, he fucked me first!’

‘And this you call “slush”?’ Claire said, unable to conceal her revulsion.

‘It’s just a turn of phrase. Every one of these files represents a life lost. You can’t hide from that. But it’s an odd fact that by far the highest percentage of homicides committed in the industrialised West, however they may initially appear, are the work of family members or other so-called loved ones. Either that, or they’re one-off events committed by people who will probably never break the law again. The result of anger, greed, jealousy … course, we need to establish that before we send them back. Oh crap, your tea’s gone cold.’

‘Doesn’t matter.’

‘I’ll make you another.’ He attended to it. ‘If there’s one thing I’m supposedly good at round here, it’s brewing up.’

Claire pulled a chair and sat down. She hoped Heck didn’t notice that she needed to.

‘The upside to all this,’ he said, as he handed her a fresh mug, ‘is that there’s no better feeling than getting justice for these people.’

‘It’ll make a change,’ she said. ‘Doing a job that feels worthwhile.’

He sat down too. ‘You must have done some useful stuff in your previous jobs.’

‘No, you were right before. Telling lies to cover ministerial incompetence, massaging figures to make inaccurate departmental forecasts look good, putting out endless spin to save someone their one-forty-K-a-year salary … that doesn’t always make you feel like a useful member of society.’

‘There you are then,’ Heck replied. ‘You’re in the right place with SCU. No one ever screws up here.’

She caught his sidelong glance, and couldn’t help but chuckle. Heck smiled – and almost on cue Gemma appeared in the doorway, peeling off her raincoat. She made a good job of disguising her double-take at the sight of them cosied up together.

‘Morning,’ Claire said, standing.

‘Morning Claire. Heck.’

Heck stood up too. ‘Ma’am.’

‘None of the other sleeping beauties checked in yet?’

‘I’m sure they’re on their way.’

Gemma glanced at her watch. ‘They’ve got forty-five minutes. If no one’s shown by then, start making phone calls. And don’t shy from using harsh language.’ She moved back out into the main corridor, but then reappeared. ‘Heck, you haven’t seen Joe Wullerton this morning, have you?’

‘Not so far, ma’am.’

‘I’ve got a note to go up and see him.’

‘Can’t help you with that.’

‘Okay.’ She breezed away.

Heck turned to Claire. ‘Forty-five minutes. Enough time for breakfast?’

‘Breakfast?’

‘There’s a smashing little deli round the corner. They do a nice egg sandwich.’