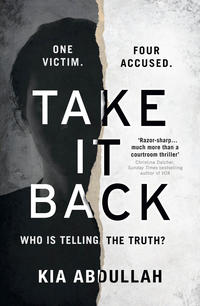

Take It Back

The blonde woman spoke first. ‘I am DC Mia Scavo and this is DC John Dexter. Can you state your names please?’

Amir offered a bright smile. ‘What’s the problem, officer?’ Then, to Hassan, ‘Has your mum been caught working the streets again?’

A snigger rose in the group and Hassan, never one to take insult lightly, bounced a hand off Mo’s chest, silencing the taller boy, knowing that he – nervy, docile, amusingly principled – was the easiest target in the group.

Mia stepped forward. ‘State your names please,’ she repeated.

Farid complied, then Mo and Hassan too. Amir sighed exaggeratedly, his eyes rolling skyward. Fine, it said. Be a joyless cow. In a tone dripping with deference, he said, ‘I’m Amir Rabbani, ma’am. How may I help you please?’

Mia’s lips drew a tight line. ‘Mr Rabbani, I am arresting you on suspicion of rape.’ Her tone was even. ‘You do not have to say anything but it may harm your defence if you do not mention when questioned something which you later rely on in court. Anything you do say may be given in evidence.’ While she spoke, her colleagues arrested the other three boys.

Amir looked to Najim for help. ‘Rape?’ he asked dumbly. ‘What are they on about?’

Mo grew pale and Farid flushed red as if the blood had drained from one boy to the other.

Najim reached out a hand, not touching Mia but close to it. ‘Excuse me, you can’t just arrest them. Don’t you need a warrant?’

Mia regarded him coolly. ‘We have reason to believe that these young men have committed a serious crime. We don’t need a warrant to arrest them for questioning.’ She turned to Amir. ‘Please come quietly. We can discuss this at the station. Your parents will be informed and will join you there.’

Amir flinched. ‘My parents are coming?’ His voice was tense with worry. ‘They’re going to kill me.’

Hassan next to him was a coil of anger. ‘This is bullshit,’ he swore. His last syllable climbed a register, creating the wobble he hated in his voice.

Mia watched them with interest, noting the change in mood at the mention of their parents. ‘Come on.’ She tugged Amir away and turned him towards the exit. He wrenched around and looked at his friends. Before he had a chance to speak, Mia pulled him back and gave him a gentle shove. As he began to walk, he heard Najim behind him. ‘Don’t worry,’ he shouted. And then, in Urdu: don’t tell the pigs anything.

Chapter Three

Hashim Khan hurried up the stairs but failed to catch the door held briefly open. At sixty-one, his legs were far wearier than even two years before. He had increasingly begun to ask himself if it was time to wind down his fruit stall but his state pension was a few years away and could he really support his wife and three children without the extra income? He pushed open the wooden doors to Bow Road Police Station and followed Yasser Rabbani to reception.

Yasser, dressed in a tailored pinstripe suit with a woollen mustard coat slung around his shoulders, looked like he’d stepped out of a Scorsese movie. Despite approaching his sixties, he was powerfully built and strikingly handsome – clearly the source of Amir’s good looks. He placed a firm hand on the counter. ‘Excuse me, I’m looking for my son.’

The receptionist, a heavyset woman in her late forties, glanced up from her keyboard. ‘What’s his name, sir?’

Hashim leaned forward, his solemn eyes laced with worry. ‘Woh kiya kehraha hai?’ he asked Yasser to translate.

Yasser held up an impatient hand. ‘Ap kuch nehi boloh. Me uske saath baat karongi.’ He urged the older man to let him handle the conversation. He spoke with the woman for a few long minutes and then, in a muted tone, explained that their sons were under arrest.

Hashim wiped at his brow. ‘Saab, aap kyun nahi uske taraf se boltay? Mujhe kuch samajh nahi aaygi.’

Yasser shook his head. In Urdu, he said, ‘They don’t have interpreters here right now. And I can’t go with your son. Who’s going to look after mine?’

The older man grimaced. What could he – an uneducated man – do for his son? Thirty-five years he had been in Britain. Thirty-five years he had functioned with only a pinch of English. Now he was thrust into this fearsome place and he had no words to unpick the threat. He wished that Rana were here. His wife, who assiduously ran her women’s group on Wednesday afternoons, could speak it better than he. For a long time, she urged him to learn it too. Language is the path to progress, she would say, only half ironically. The guilt rose like smoke around him. Why had he spent so many exhausted hours by the TV? There was time for learning after a day on the stall. Cowed by embarrassment, he let himself be led away, along a corridor, into an austere room.

Farid sat alone under the fluorescent light, fingers knitted together as if in prayer. He looked up, a flame of sorrow sparking in his eyes. He offered a thin smile. ‘It’s okay, Aba,’ he said in Urdu. ‘Nothing happened. They just want to question us.’

Hashim sat down with his hands splayed on his knees and his joints already stiffening from the air conditioning. He stared at the wiry grey carpet to still the nerves that jangled in his limbs.

Hashim Khan had learnt to fear the white man. After moving to England in the seventies, he had learnt that wariness and deference were necessary in all dealings with the majority race. Now, called upon to protect his son, he knew no amount of deference would help. The door shut behind him with a metallic thud. He closed his eyes and whispered a prayer.

‘Mr Rabbani, please take a seat. Would you like a drink? We have coffee, tea, water.’

‘No,’ said Yasser. ‘Tell me what this is about or I’m calling a lawyer.’

Mia was unruffled. ‘If your son is guilty, he probably needs one. If not, he’ll likely be out of here in an hour.’

Yasser scowled. ‘Then tell me what this is about.’

Mia pointed at a chair and waited for him to sit. She explained that the interview was being recorded and ran through some formalities.

Amir shifted in his seat, feeling unnaturally small next to his father’s frame.

Mia began, ‘Amir, can you tell me where you were on the evening of Thursday the twenty-seventh of June?’

‘Yes. I was at home until about 7 p.m., then I went to a party with some of my friends.’

‘What time did you get there?’

Amir shrugged. ‘I don’t really remember.’

‘Okay, what did you do after the party?’

‘I went home.’

‘What time did you get home?’

‘I’m not sure. About 1 a.m.’

Mia made a note. ‘And you went straight home after the party?’

‘Yes, I just said that.’

Mia smiled coldly. ‘Well, what if I said we have reports of you attending an after-party of sorts at seventy-two Bow Docks, a derelict warehouse approximately seventy metres from the location of the party?’

Amir frowned. ‘That wasn’t an after-party. We were just fooling around on our way home.’

Mia glanced at the father. He was like a nervous cat, poised to pounce at any moment. Perhaps a soft approach was best here. ‘Okay, it wasn’t an after-party – my mistake. What did you boys get up to there?’

‘We just hung out.’

Mia tapped the table with her index finger. ‘And by that you mean?’

‘We just talked, played music and …’ He swallowed hard. ‘We had a smoke.’

Amir’s father snapped to attention. ‘A smoke? Of what?’

‘Dad, I’m sorry, it’s not something we do all the time. Just sometimes.’

‘A smoke of what?’

The boy stammered. ‘Ganja.’

Yasser shot back in his chair. ‘Tu ganja peera hai? Kahan se aaya hai? Kis haraami ne tujhe yeh diya hai?’

‘Aba, please. It was just once or twice.’ Amir tried to push back his chair but it was bolted to the floor.

‘I work all hours of the day to give you the life you have and you’re going to throw it away on drugs?’

Amir shrank beneath the ire as if physically ducking blows. ‘Dad, I swear to God, it was only once or twice. Kasam.’

His father’s voice grew stony. ‘Just wait until your mother hears about this.’ Yasser shook his head in disbelief. ‘We’ll deal with this later.’ He exhaled slowly and turned to Mia. ‘I’m sorry, officer. Please continue.’

Mia felt a flicker of grudging respect. It was obvious he cared about his son’s mistakes. Too often she saw young men trudge through here like ghosts, floating from one place to another with nothing at all to tether them. Yasser Rabbani clearly cared about his son.

‘So you were smoking cannabis,’ said Mia. ‘Was there alcohol?’

Amir vigorously shook his head. ‘No.’

Mia made a note to ask again later. ‘Who else was there?’

Amir nodded at the door. ‘Mo, Hassan and Farid.’

‘Did anyone join you throughout the course of the night?’

‘No.’

Mia caught the fissure in his voice. ‘Amir, you should know that our officers are collecting your computers as we speak and we’ll be examining your phones. If you or your friends are hiding something, we’ll find out.’ She smiled lightly. ‘Don’t you watch CSI?’

Amir blinked. ‘Okay, there was one other person there but I really don’t want this to get out. I’ve been trying to protect her forever.’

‘Who’s that?’

He hesitated. ‘Her name is Jodie Wolfe. She’s a girl from school. She has something called neurofibromatosis which messes up your face. We had a class about it at school but the kids called her the Elephant Woman anyway.’

‘What was she doing at the warehouse?’

Amir shifted in his chair. ‘She’s a sweet girl but she can be a little bit … sad. She’s had a crush on me since year seven and even now, five years later, she follows me around – pretends she just bumped into me.’

‘Is that what she did that night? Pretend to bump into you?’

Amir shook his head. ‘No, even she wouldn’t be that sad. She said she was looking for her friend Nina. She’s always going off with different boys so Jodie must’ve lost her. She said she saw a bunch of us heading here and figured there was some kind of after-party.’

‘Did you invite her to join you?’

Amir scoffed lightly. ‘No, she just turned up. We were hanging out – just the boys.’

‘So she turned up at the warehouse or joined you before?’

‘Yes, she turned up at the warehouse.’

‘Then what happened?’

Amir frowned. ‘She asked if she could have a smoke. The boys didn’t want to share one with her. I didn’t say anything. I mean, she’s not diseased or anything but she’s scary to look at because of her condition so I could understand why they said that. She seemed upset so I tried to comfort her.’

‘How?’

He shrugged. ‘I put my arm around her and told her to ignore them.’

Mia couldn’t place his emotion. Guilt? Shame? Embarrassment?

‘Then she …’ his voice trailed off.

‘Then she?’

The boy’s face flushed red. ‘She whispered in my ear and said she would do something for me if we got rid of the boys.’

Amir’s father stood abruptly. He turned to the door and then back to his son. He opened his mouth to speak but then closed it again. Finally, he sat back down in silence and trained his gaze away from his son, as if the space between them might swallow the mortification of what was to come.

Mia leaned forward. ‘You said that Jodie whispered in your ear. What did she say?’

Amir glanced sideways at his father. ‘She—she said she would give me a blowjob and then started describing it. I was stunned. I always had this idea that she was a sweet girl.’

‘How did you respond?’

‘I took my arm off her and told her to go home. The boys started laughing and making kissing noises. I was really embarrassed so I started on her too.’ He paused, shifted in his chair and made a visible effort to focus on Mia. ‘I’m not proud of it but I said there’s no way we’d share the spliff with her; that we didn’t want to swap saliva with a dog. I knew she was hurt because I’ve always been alright to her but—’ Amir pinched the skin between his brows, as if to ease a headache. Then, he spoke with surprising maturity, ‘Look, I have an ego – I know that – and egos are fragile. The kids at school look at me and see the cricket captain, the guy that gets all the girls, the guy that has it all – and if it got out that I was cosying up to the school freak, then my reputation would take a hit. I like Jodie but she’s not the kind of girl I want to be linked with that way, so I had to put a stop to it. She got upset and started crying. I felt bad but I told her to leave.’

‘And then?’

‘She left. She was crying and I think she may have had a drink because she was stumbling about a bit, but she left. Despite what the boys say, I think we all felt a bit bad so we wrapped it up, finished the spliff and went home.’

‘And have you seen Jodie since then?’

‘No. Why? Is she okay?’

‘Jodie says she was raped that night.’

The boy’s face turned ashen. ‘She’s the one who said I raped her?’

Mia’s voice was cold. ‘Yes, Mr Rabbani. She’s the one.’

DC Dexter put his elbows on the table. Calmly, he repeated himself, ‘Jodie Wolfe said you, Amir and Mohammed raped her that night while Farid stood by and watched. What do you have to say to that?’

‘I don’t believe it,’ said Hassan, his eyes ringed with pale, uncomprehending horror. He looked to his father. ‘Aba, Allah Qur’an, that’s a lie.’

Irfan Tanweer was an older version of his son: short and wiry with tight ringlets of black hair atop a thin and hawkish face. His beady eyes danced with suspicion as he leaned forward and, in a thick Bangladeshi accent, said, ‘You must be mistaken. My son – he is a religious boy. He would not do this.’ He held out a hand to quieten his son. ‘We are good people, sir, Mr Dexter. I have worked hard to make a home for my wife and my boy. I have a decent boy. Of that I am very sure.’

Dexter nodded placidly. ‘That may be true, sir, but we need to know what happened. We need to hear your son’s side of the story.’

‘There is no “side” of the story. My son will tell the truth.’ He turned to Hassan. ‘Hasa kotha khor,’ he urged him to start.

Mo ducked in embarrassment when his father gripped the edge of the table. Each fingernail had a dried crust of blood along the cuticle. His father wore butchers’ gloves at work and washed his hands thoroughly but that thin crust of blood seemed to always cling on. The two didn’t look like father and son. Zubair Ahmed with his burly shoulders and broad chest was a pillar of a man. Mo was tall too, but thin and awkward. Where Zubair’s hands were strong and meaty, Mo’s were thin and delicate, almost effeminate in their movement as they fiddled now with his glasses.

He sat forward in his chair, shoulders hunched as if he were cold. ‘I’m not confused, sir,’ he said. ‘We didn’t hurt Jodie – not the way you say we did.’

The detective watched him with reproach. ‘I think you are confused, son, or you would see that the wisest thing for you to do now is to tell the truth.’

Mo remembered the sharp pain in Jodie’s eyes and the sting of betrayal when he sided with the lads. His obedience to them had cost him too: his pride, his integrity, his belief in his own valour. His complicity felt viscous in his throat and he swallowed hard so that he could speak. ‘I shouldn’t have let them treat her that way. They shouldn’t have called her a dog.’ He hesitated. ‘But they were just words. We were in a loose and silly mood and,’ his voice grew thick, ‘we took it out on her because she was there and she was weak.’ He blinked rapidly, sensing tears. He hated that they’d targeted Jodie. He, all too familiar with the sting of mockery, hated that he’d let it happen. With a deep breath to steady his voice, he said, ‘We hurt Jodie but not in the way she says.’ He swallowed. ‘We were awful to her, but what she said did not happen and I’m sorry, sir, but I’m not confused about that.’

Amir sat in silence, his mouth open in a cartoonish O. His father spoke to him in a burst of Urdu, the long vowels urgent and angry. A lock of his salt and pepper hair fell free of its pomade and he swiped at it in a swift and severe motion that betrayed a slipping composure.

Mia firmly quietened him and urged Amir to speak.

‘But it’s Jodie …’ he said. ‘You’ve seen her. I – we – wouldn’t do something like that.’ He ran a hand across the back of his head. ‘This is so bizarre.’

Mia studied him closely. He seemed neither worried nor guilty – just confused. She spoke to him in a low voice. ‘Maybe it wasn’t you. Maybe it was Hassan and Mohammed that did it and you and Farid just watched. Could that have happened and Jodie just got confused?’

He frowned. ‘Look, we were all together the whole time. There is no way any of the boys could have done anything to Jodie and they’ll all tell you the same. Nothing happened.’

Mia’s face grew stony. ‘Then you won’t mind giving us DNA samples.’

Amir shrank back in his chair, his athletic frame suddenly small. His father held up a hand. ‘Don’t you need a warrant for that?’

Mia leaned in close. ‘Mr Rabbani, your son is under arrest for rape. Do you understand how serious that is? We can take DNA samples if we want to.’ She paused. ‘And we want to.’

Amir grimaced. ‘I didn’t do it.’

Mia smiled without humour. ‘Then we don’t have a problem, do we?’

It was an hour later that she watched the group of men file out of the station. She turned to Dexter. ‘I can’t work it out. Do you think they colluded beforehand?’

Dexter’s face creased in thought. ‘I didn’t get a sense of rehearsed answers.’

‘Were either of yours even a little bit tempted to shop their friends?’

‘No. They’re too clever for that. They know all about divide and conquer.’

Mia frowned. ‘I just can’t work it out,’ she repeated. She stared at the door, still swinging on its hinges in the wind.

Sameena Tanweer sat motionless, her tiny frame comically small on the sofa. A network of fine grey cracks spread across the leather and a fist-sized patch stained one of the seats. She had caught Hassan as a child pouring the contents of her Amla hair oil in a concentrated pool on the spot. She had tried to hide it with homemade sofa covers, flowery and powder blue, but her husband had shouted. He was still bitter about spending two months’ wages on the three-piece suite all those years ago and damn him if he was going to cover up real leather with cheap fabric like a fakir.

She sat there now, compulsively tracing the stain as the phone beside her hummed with the news. Her husband’s tone had been rushed and harsh, untempered by words of comfort as he told her of their son’s arrest.

In her mind, she searched frantically through a list. She couldn’t call Jahanara’s mum. That woman would spread the news to five others before she even came round. What about Kulsum? Wasn’t she always talking about her lawyer son? Or was he an accountant? Sameena couldn’t remember. Did she, after thirty years in Britain, really have no friends that she could call? Her social circle was limited to her neighbours, each of whom visited her several times a week to gossip about the unruly daughters and unkempt houses of their mutual acquaintances. Sameena always listened with patience but never partook in the gossip. She knew that every family had its flaws and she refused to pick apart another woman’s life.

After a long minute of inertia, she stood and hurried to Hassan’s bedroom, hitching up the hem of her sari on the stairs. Inside, she was hit by the musty aroma of a teenage boy. Last Tuesday she had hovered by the door pleading to clean his room but Hassan had swatted her away like a fly.

‘Leave the boy alone,’ her husband had said, the tetchiness clear in his tone. ‘He’s a teenager. He needs his space.’ Interestingly, he often took the opposite view.

Sameena stepped into the smell and opened a window. Then, thinking no further, she gathered armfuls of clothes and in three trips took them to the bathroom. She stripped his sheets and checked under the bed and mattress for secret hiding places. She pulled out his socks and underpants and added them to the pile.

‘It’s fine,’ her husband had said. ‘Don’t get hysterical.’ But she had heard the horror stories. She had heard how Muslim boys were shot in raids and evidence planted in computers. She had to protect her son.

When the bath was full of clothes, she took an armload and stuffed it in the washing machine. The rest she hosed down with two cups of detergent. She hurried back and gathered all the electronics strewn across his room: his laptop, his dusty old Xbox, a mobile phone with a shattered screen and several USB sticks. She took them to her room and scanned her furniture for a lockable hiding place or secret cavity. She thought desperately of a place to deposit the loot.

Finally, she rushed to the kitchen and located the large piece of Tupperware her husband used for leftovers from the restaurant. Inside, she lay the items in layers: first the laptop, then the console, then the phone and USB sticks slotted around the sides. With everything neatly inside, she shut the lid, wrapped the box in several bags of plastic and took it out to the garden. Gathering a fistful of her sari, she bent with a trowel and began to dig. When she had a hole almost two feet deep, she pressed the container inside and covered it with soil. She patted it down and scattered stones and leaves across the top to disguise the fact that it had been disturbed.

She stood over the spot in silence until the evening breeze made her shiver with cold. A vision of a nine-year-old Hassan crept into her mind, up in his room one sunny afternoon, standing over his cousin as quiet as a mouse. Her hands began to shake. She was doing this to protect her son.

Back inside the house, she laid a fresh set of sheets on his bed and then gathered an armful of her husband’s clothes. Carefully, she arranged the garments around Hassan’s room: a jumper askew on the back of a chair, balled socks at the foot of the bed, a pair of trousers at the bottom of the closet. It was only when the first wash cycle spun to a close that her heartbeat began to slow. What would those kafir do to her boy?

She unloaded the machine and was crouched down beside the basket when she heard the first knock. She froze for a moment, flinching when it came again, hard and insistent. She crept down the stairs and peeked through a window, coming face to face with a uniformed policeman. He pointed to the door.

‘Open up please, madam.’

Sameena stepped back from the window, her head thumping with dread. A heavy fist hammered on the door, the calls loud and impatient. She couldn’t just leave them on the doorstep, rousing Jahanara’s mum and Mrs Patel across the road. She gathered up her nerve, stepped forward and turned the latch.

A heavyset man, too fat to be a policeman, held up a black wallet with a badge and ID. He spoke to her with surprising calm and then, without invitation, he stepped inside. Two other men followed. They asked her questions she did not understand, the only familiar word her son’s name said over and over. Hassan, Hassan, Hassan. What fate had he drawn to this house?