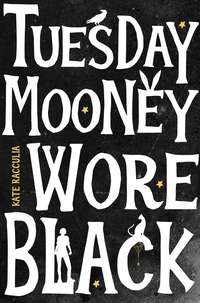

Tuesday Mooney Wore Black

“I doubt that.” Tuesday narrowed her eyes.

The guy frowned. Then he muttered, “I met you, I liked you, I feel bad that I flaked on the fifty thousand. And, well: nobody in my … complex family knows who you are, which means you can operate with a degree of anonymity.”

“Fine, that’s why me. Why you? What does the collection have that you can’t get somewhere else? You’re almost passing for aspirational middle class in this J. Crew catalog drag right now—”

“Hey,” the guy said, and smoothed his blue sweater over his stomach. “This is not J. Crew.”

“—but I bet you’ve got four figures in loose change in your pockets. From a financial standpoint, to you, Pryce’s ‘great fortune’ has negligible value. Forgive me for questioning your motives, but contracting me for this is like – if I were to contract Dorry here to help me hunt down a pack of gum.”

“I would do that,” said Dorry.

“I know you would, kid,” said Tuesday. “No, not even a pack of gum. It would be like me hiring a PI to find a wad of gum under a desk. So why do you, dirty, filthy, stinking-rich Nathaniel Allan Arches” – with every adjective Tuesday lobbed at him, he nodded – “want a wad of used chewing gum?”

He tugged on his right earlobe, and Dorry blinked. A tell. He had a tell. The next thing out of his mouth would be a lie, or, if not a direct lie, something that wasn’t entirely the truth. Her mother had had a tell: whenever she was about to drop a Wild Draw Four on Dorry in Uno, she tapped her fingers on the cards.

He inhaled. His chest rose. So many tells, thought Dorry, and looked at Tuesday, who had no tells, or at least none that Dorry had ever noticed.

“Why does everything have to be about money?” he said. “Honestly, and I would expect someone who roots around in the digital drawers of rich people for a living to know this already, if you have enough money, it stops meaning anything. You can’t touch it or taste it or feel it. Then the things that matter become what you can touch, or taste, or – feel.”

“Objects, you mean. Something in Pryce’s collection,” Tuesday said.

“Let’s just say” – his already deep voice lowered, which made the bottoms of Dorry’s feet tingle – “that the value is sentimental.”

Tuesday didn’t respond.

“One hundred fifty thousand,” he said. “Final offer.”

“One hundred fifty is my retainer, plus expenses,” said Tuesday. “I want a working partnership. We split the detecting, the legwork, fifty-fifty. If we win, we split the reward fifty-fifty. I’ll take half, you take half. Or you can buy me out, for however much Pryce’s estate is currently valuing whatever the prize turns out to be.” She smiled. “But for no less than five million.”

Dorry’s throat dried up. She made a little coughing sound halfway between a gasp and a laugh.

“Oh, now you’re playing hardball,” said Archie.

“Still not,” said Tuesday, grinning. “But closer.” She stuck out her hand.

Archie paused.

“Why does everything have to be about money?” Tuesday said. “C’mon, I know you’re good for it. I’ve done the research.”

He slid his hand into hers.

“We start tonight,” said Tuesday. “Because you know anyone else who’s serious has already started too.”

So Archie came in. He introduced himself to Dorry with a handshake, and Dorry felt herself start to giggle, because seriously, a handshake? Then her hand went sort of rigid in his warm grip, and after he let go, her first thought was I did that wrong. Or did she? How was she supposed to shake a guy’s hand, a guy who wasn’t her dad’s coworker, wasn’t her mom’s old college friend, wasn’t saying, while they held her cold hand, I’m so sorry for your loss?

They all sat at Tuesday’s rickety Ikea table and ate and strategized.

“Tell me about Pryce,” said Tuesday.

“He was a weirdo. A true-blue, first-class, dyed-in-the-wool weirdo.” Archie dipped a piece of naan into the malai kofta sauce. “New money, vulgar money. Barely tolerated. And I really don’t think he gave a fuck. Oh—” His eyes darted to Dorry.

Dorry snorted. “Dude,” she said, “you kiss your mutha with that fucken thing?”

“This is your influence?” he said to Tuesday. “Look what you’re doing to the youth.”

“I believe the children are our future,” said Tuesday.

Dorry cleared her throat.

“Oh children,” said Tuesday, “do you have something to say?”

Dorry felt herself blush. She did. She had a lot to say. She coughed. “Um, I think I might – know where to start looking.”

Tuesday’s head jerked like a bird’s. “Wha— that’s great. Where?”

Dorry looked at Archie, blushed again, and looked back at Tuesday. “Do you really trust this guy?” she asked. She didn’t, but she trusted Tuesday completely.

“I trust his money,” said Tuesday.

“I want a cut,” Dorry said.

Tuesday cackled. “And that,” she said to Archie, “is hardball. You got it, kid. I can’t spend five million all by myself.”

“Actually, you can,” said Archie.

“Well, I have no plans to go to college again. Dorry needs it more than I do.”

Dorry knew she was still blushing – she could feel her face almost pulsing, and a cool tight spot in the middle of her forehead – and when she stood up, she shook a little. Even if Tuesday only shared one million dollars, it meant Dad could afford the apartment for as long as they wanted. It meant they would never have to move back to the suburbs, or buy a car or have to drive one. And if neither she nor her father ever learned to drive, they could never hit a patch of black ice and smash through the guardrail of a bridge and sail into the river below. They could never be missing for two days in a blizzard, sealed under ice and snow.

They could never drown in freezing water with their seatbelt still on.

She grabbed the letters she’d been reading before Archie knocked on the door. Gunnar was sleeping on them (of course), and was less than pleased to be displaced. “Pryce had a real problem with Valentine’s Day,” she said, handing the printouts to Tuesday. “Every year, he wrote about what a sham it is. He calls candy hearts hideous hearts.”

She heard Tuesday suck in a breath.

“I started circling the first words, then the first letters, of each Valentine’s clipping. In order. So far I have P A R. It could be spelling a word, right? And didn’t the obit say something about hearing the city’s hideous heart?” She was talking too fast. “We’d have to find them all to be sure, but I bet – I bet the first letter of every Valentine’s letter spells Park. As in Park Street.”

“Park Street station. The oldest subway in America. Of course,” said Tuesday. “Where else but under the ground would the old city’s heart be beating?”

“Where else?” said Dorry. Her own heart was leaping like it would never stop.

4

THE CITY’S HIDEOUS HEART

Tuesday, on the sidewalk outside her apartment, snapped her bike helmet’s chin buckle.

She couldn’t believe she was doing this.

But of course she was doing this. It was the most fun she’d had in an age.

“Archie,” she said.

Nathaniel Arches turned around. “What?”

“I never told you my last name,” said Tuesday.

“I never told you mine either.”

Fair point.

“Are you so surprised by my resourcefulness?” he asked.

“Your resourcefulness,” she said, “is borderline creepy.”

“Isn’t your whole job borderline creepy?”

“I don’t cross the border. I have a code of ethics. I don’t, for example, show up at the apartment of someone I have researched.”

“You just write up dossiers about us that we don’t even know exist.”

“Dossiers that help the people I work with strategically persuade you to become just slightly less rich, so the hospital can build a nice new oncology suite. Besides,” she said, “you knew. You know. You gave those interviews.” He pulled his own helmet over his head as she continued. “You tweeted those memes. You put an idea of yourself out there for me, for anyone, to find.”

“Did you ever consider,” he said, “that I was using my resourcefulness to impress you?” His voice was muffled by the helmet, but his eyes were visible, the same eyes she’d recognized in the ballroom of the Four Seasons. “And that with our powers combined—”

He threw his leg over the motorcycle, parked illegally in front of her building’s driveway. Tuesday didn’t know much about bikes, but she knew his was a Ducati, and that it was very cool.

“Your game needs work,” she said.

The first glow of sunset was disappearing over the top of her apartment building when she climbed on the bike and locked her arms around him.

“Seems like it’s working okay,” he muttered, and ripped the bike to life. She was charmed, begrudgingly; it was the cheater’s way of getting the last word.

They rode through the blue night air, up and over the Somerville streets, on the crumbling elevated highway, past the Museum of Science, crossing the Charles River into the white lights of the city. They swung low through the winding snake of Storrow Drive, pulled off at Beacon, looped around the Public Garden, and slalomed down into the parking garage beneath Boston Common. There was so much beneath the ground in Boston: cars and tunnels and tracks and subway trains. Literal garbage, under the Back Bay – an entire neighborhood built on landfill. No wonder Pryce started his hunt here, at the center of the city, on the corner of the Common, in one of the oldest subway stations on earth. Everything began beneath the ground.

Archie cut the engine. “That tickles,” he said, and Tuesday realized her phone, tucked in her inside jacket pocket, was vibrating. Dorry, probably. She’d been pissed to be left behind, but she’d backed off once Tuesday pointed out that (a) her father would have a fit if he found out his daughter’s tutor had taken her on a wild treasure hunt, (b) they needed someone at mission control, someone who could call the police if they stopped making contact, and (c) only two people would fit on the bike. “I’ll give you the first two,” Dorry’d said. “But the third reason is crap. It’s a T station. I don’t need to ride with you guys to get there.”

But it wasn’t Dorry. It was Dex.

Did you solve it yet you’re killing me

She felt a little guilty. For forgetting about him. And for not, with a fleeting adolescent protectiveness, wanting to share.

Yes! Park Street. Heading there rn, stay tuned

It was officially blue-dark in the Common when they came up out of the garage, only a little past seven, though, so the paved paths were still full of people. The closer they got to the station itself, the brighter and noisier it was. Under a streetlamp, two guys in bandanas banged syncopated beats on upturned plastic tubs while a third did the worm on the sidewalk, the last of the day’s buskers, playing, now, for the locals. Drumming in the city made her walk differently. It loosened her hips. Brought her back into her body, ready to bend and to move.

Her phone buzzed again.

WHAT you mental minx

I knew you’d figure it out

She texted back, Next Dorry did, not me, and felt a pop of pride for her neighbor. Dorry was a good kid. The best kid she knew. The kind of kid who made having kids seem particularly great, if you wanted to have kids, which Tuesday didn’t.

“So what are we looking for?” asked Archie.

“I have no idea.”

“Then let’s go see what we can find,” he said. “Maybe it’ll scream at us.”

Park Street had two entrances, gray iron-and-stone structures like twin mausoleums dropped at the edge of the Common, heralded by the symbol of the Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority: a capital T in a black circle, branded on white like the M on an M&M. Tuesday and Archie took the right entrance, flowing with the human tide down yellow-edged steps to the first of two levels of trains. The upper Green Line platform held the remnants of rush hour, exhausted-looking commuters, eyes glazed, ears sprouting white buds and wires, lazily poking at their phones or burying their noses in books. A girl with pink and purple hair – Berklee student, for sure – was slow-jamming the theme from The Simpsons on tenor saxophone, smooth and sweet, and a youngish man with dark hair silvering at his temples smiled at her. He dropped a crisp bill into the instrument case open for change at her feet. It floated down like a leaf.

Tuesday stalked along the right side of the platform, dodging T riders, following the yellow rubber edge all the way to the end. Nothing. “I don’t know what I expected,” she muttered. “Kilroy saying ‘Vincent was here’? ‘Follow to clue’?”

“Um,” said Archie, pointing over her shoulder. “That seems pretty close.”

On the other side of the tracks, spray-painted and dripping on the dirty white and gray plaster of the wall, was a black bird. Head up and stiff. Wings folded back. The very silhouette of a raven, if it were sitting, say, on a bust of Pallas above one’s chamber door. A shaky scrawl in white chalk floated above the raven’s head. She had to step closer to read it: The prince of darkness is a gentleman!

“I mean,” said Tuesday. Her pulse picked up speed. She imagined the platonic ideal of a lawyer, three-piece suit, leather attaché, leaping over the tracks with a stick of chalk and a raven stencil, shaking a can of spray paint like a maraca: Pryce’s helper. Leaving clues around the city. “We shouldn’t be worried that it seems too easy, right? Pryce wants us to follow him. He wants people to solve it. He’s not trying to hide.”

The painted raven’s beak and one spindly foot, raised, were pointing toward the dark of the tunnel, beyond the platform, where the tracks disappeared on their way to Tremont Street station.

She took a picture on her phone and sent it to Dorry.

Dorry responded in four separate texts:

O

M

F

G

“I have no idea,” said Archie, drawing Tuesday by the elbow to conspire, “what sort of security cameras are set up here, but I’m willing to make a run for it down the tracks to see what we can find.”

“I’m less worried about security cameras than I am about – well.” Tuesday rolled her head to indicate the other people milling on the platform. “We’re about to become the definition of see-something-say-something.”

“They’re not going to see or say anything,” said Archie. “Look at them. They’re zombified. We wait until another train pulls into the station and they’ll all turn to look at it like—” He whipped his head to the side. “Squirrel.”

She swallowed. She felt a little dizzy. A little too warm. A little shaky.

On the internet, when she was researching, she was fearless. She would chase the tiniest clue down any number of research rabbit holes. This was just a forty-foot walk down a dark tunnel. Where she wasn’t supposed to go, technically – but, unlike the internet, once she was gone, there would never be any trace of her. No IP data, no browser history, no nothing. Online, she left tracks. Only in the world could she actually be invisible.

This was real, and her body was reacting accordingly.

She cleared her throat. “We have options,” she said. “We should discuss them. One: we wait for a break between train cars, and we sneak down the side of the tracks. Two: one of us sneaks, and one of us distracts. And I suppose there’s a third option, where we locate the station manager and tell him what we’ve found and wait for the police to come and supervise the whole thing.”

Archie’s lips slid slowly into a grin. “I don’t want to do that,” he said.

“You are bad news,” said Tuesday. “But I don’t want to do that either.” Her heart bumped. There was a whole world underground, of access doors and unused passages, old stations and tunnels. How deep was Pryce going to ask them to go?

Five million dollars could bail her out of jail more than a few times.

She looked across the tracks at the DANGER DO NOT CROSS signs posted every ten feet. She looked at Archie. He was rocking back and forth on his limited-edition Pradas, tenting his fingers like Mr. Burns, looking more mad scientist than sexiest new capitalist. It made him hotter. Stupid hot. One step removed from filthy hot. Tuesday’s taste had always run to the Doc Browns of the world, the wild-eyed renegades and rule breakers. But Emmett Brown broke rules because he wanted to find new roads. Archie broke rules because he thought, as did so many born under a dollar sign, that the rules applied to other people. This was less attractive, philosophically.

But it wasn’t unattractive.

The metal-on-metal shriek of a train approaching on the opposite track made her decision for her.

She grabbed Archie’s hand and ran into the dark beyond the platform.

Her feet kicked up stones. She crossed over a tie with each stride. She didn’t stop until they were well inside the tunnel, far enough not to be seen from the station but not so far that the station’s ambient light couldn’t reach them. Tuesday instinctively hopped over the rail and threw herself flat against the wall, and then realized the wall must be disgusting – all the walls were black with grime, the whole place had needed a power wash for half a century – and flinched forward, her foot connecting with an empty plastic cup. It bounced up and over the rails, clear dome winking in the low light, and rolled to a rest against some kind of train machinery. A signal box, maybe, or a breaker, levers sticking up out of the ground.

She looked behind her. No klaxons. No shouting. No reflector-stripe-uniformed T personnel blinding her with a flashlight.

She let go of the air in her lungs.

“Told you,” said Archie. This time, he took her hand. “Come on,” he said. “Watch your – watch your feet. You don’t want to step on a rat.”

“New York has rats,” Tuesday said. “We have cute little mice.”

“I doubt you’d want to step on one of them either.”

She heard shuffling and then there was light, tiny but piercing, from Archie’s iPhone. She pulled her phone out of her pocket and fired up her own app.

“So we’re here,” she said. “Huh.”

“Not as magical as you’d hoped?”

Yes and no. They were a few yards away from the junction that brought the station’s twin tracks together, en route to Tremont, and the parallel rails coursed through the darkness, crossing, shining, melting together, iron arteries flowing from a metal heart. It was also full of garbage. Dunkin’ Donuts cups and Coke bottles and wrappers and plastic bags and assorted other, unnamable detritus. She felt it before she knew it was happening – a shift beneath her feet, like an earthquake’s ghost – and the train that had been pulling into the station when they made a run for it coasted down the opposite track, through the junction to points beyond, clacking through the darkness like a great green mechanical caterpillar.

She threw her phone’s light up on the wall. Dirt. More dirt. Here, a door, with an MBTA PERSONNEL ONLY sign, half open – a storage closet. Inside, buckets and tools and wires and plastic yellow CAUTION/CUIDADO signboards with graphics of flailing stick figures. Next to the door, more dirt and graffiti, all in caps: YANKEES SUCK.

“Hey!” Archie’s voice carried from ahead. “I found – I don’t know. Over here.”

Tuesday followed his voice around a corner into an alcove, clear from the path of the train, partially made of brick. Bright, clean brick. So clean it couldn’t possibly have been down in the tunnel for very long. And over the brick, someone had spray-painted more graffiti, though the sentiment was somewhat more refined than YANKEES SUCK:

IN PACE REQUIESCAT

“Rest in peace,” said Archie.

Tuesday put her hand on the bricks. The mortar felt loose, powdery.

Shit.

“This is it. This is what we’re supposed to find. There’s – I hope to God there’s only a clue bricked up inside and not some poor schmuck. Buried alive.” Her stomach was doing something she wasn’t sure it had ever done before. It felt very dense, like it had its own specific gravity, distinct from the rest of her body. “In a jester’s costume,” she croaked.

“Ah,” said Archie. “The cask of amontillado marks the spot.” He nudged her with his elbow. She tried to nudge back.

But she felt sick and weak, and all she could think of was the last time she read “The Cask of Amontillado.” In high school, under duress in English Ten. Ms. Heck’s class.

With Abby Hobbes.

Abby used to sit at the desk behind her. Abby kept up a running commentary throughout class, even though they both loved it, and loved Ms. Heck. Not being able to shut up was how you knew Abby Hobbes loved something. And Abby loved that “The Cask of Amontillado,” with its pathetic, drunk clown buried alive, was Tuesday’s Achilles’ heel. Are you seriously freaked by this? This is so tame. This is lame. It’s masonry. It’s a drunk asshole and a psycho and unnecessary home improvement. “For the love of God, Montresor!”

Tuesday could still hear her cackle. Focus on the task, she told herself. Focus. There’s nothing here that can actually hurt you. It’s theater. It’s a game. It’s one hundred fifty thousand dollars plus expenses in your pocket. It’s the possibility of five million more.

“We need a tool, a hammer or something.”

“How about an elbow?” said Archie. “Or a shoulder?” And he threw himself sideways at the wall.

It did not work.

Tuesday laughed a weak laugh and felt, for the moment, better. When she realized Archie was smiling at her, and that he hadn’t really expected to break through, she thought seriously about pushing him up against it and sticking her tongue down his throat.

Focus, she told herself.

They found a hammer and a rubber mallet in the supply closet. Tuesday took a picture of the graffiti, one without and one with Archie (“Should I make finger guns?”), and sent them to Dorry, who responded immediately: !!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!! Then they stood in front of the bricked-up wall, weapons raised like bats. Tuesday paused.

“This is not how I expected my night to turn out,” she said.

“Me neither,” said Archie.

They swung.

Tuesday had never tried to break down a wall before, but she could tell right away this wall had been built to fall. Whatever the mortar was, it was still soft; the bricks started to give on the second swing. By the fifth swing, they’d knocked whole chunks clear. They pulled the wall down with their hands, brick by brick.

Her feet felt the earthquake-ghost again, stronger this time, closer – vibrating down their track, not the opposite one. “Careful,” she told Archie. “I think a train is com—”

Archie chose that exact moment to shine his phone on the black hole they’d been making.

And on the corpse of Abby Hobbes hanging inside.

Strung up by her wrists. A multicolored ruff around her neck. Her face a bloated gray moon. Lips black. Soft rotten holes instead of eyes. Found. After all these years vanished, found. Found dead and bricked up in a tunnel underground.

Tuesday didn’t scream. Later, she would be proud of herself for at least that.

What she did was turn and bolt out of the alcove like an electrified rabbit, toward the oncoming path of a Green Line car that would have splattered her across the tracks if Archie hadn’t lunged after her, flung his arm around her waist, and yanked her back from the edge and into the pile of dust and bricks.

The train ding-dinged.

“We’ve been made,” Archie gasped.

The train car’s brakes squealed, then shrieked.

Tuesday couldn’t move. She couldn’t breathe. She couldn’t close her eyes. She couldn’t—