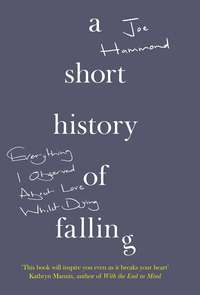

A Short History of Falling: Everything I Observed About Love Whilst Dying

This is a special subcategory of falls – perhaps the worst kind – because they linger and they haunt, they spill and they drift. These are the almost falls – the ones that never happen; the ones that nearly happen. The moment of knowing a fall is happening. Not fearing it. Knowing it. Even if that moment is fractional, and then snapping out of that space. It’s the waterboarding equivalent of falling, because it feels like it’s happening but it’s not. The heart turns inside out like a rubber cup and then pings back into shape. It’s time travel, or two parallel moments coexisting: the disastrous one and the banal one, with thoughts rattling helplessly between them like a pebble in a bucket. The finial was out of reach, but the banister rails weren’t. I never forget the almost falls. Not the bad ones.

One pebble has been rattling around for the last nine years, getting more clattery with each recollection. I was on a path on the edge of a ravine. I must have stopped for something. A view? Maybe I needed a piss. Gill was ahead. I could see her disappearing as she traversed the sharp cliff along a loose, flinty path. We were trekking on the Indian side of the Himalayas, without a guide. We were alone. And as I skipped forward to catch up, my toe caught a rock and my two insteps collided. After a stumble forwards, the thick sole of my right boot skidded flat and I came to a stop. I was on my own in the silence. Gill was out of view, with the precipice just ahead. I thought of the degrees by which falls can happen: the strength or slightness of the connection that one toecap might make with one heel, in the process of stumbling and clattering. And how close I came to a more prolonged stumble, and then to nothing, to disappearing over the edge, in the silence, out of view. Imagining the experience of Gill as she stepped back on herself into a mystery. To an empty path. It’s the silence of that moment that concentrates this memory. The fitting stage that it was for an ending. The intimation of an ending, even though it wasn’t.

Every thought I have had about that moment has been more profound than the one I had at the time. I shook it off, but it has stayed with me and has grown in the dark with each recollection. I didn’t mention it to Gill when it happened. I just trotted on and caught up. Because nothing actually happened – nothing that I felt I could communicate.

I’m falling now. But this time it is real. Unlike you, perhaps, I know I am dying. And because of that I fear it less.

As I progress down the upstairs landing, holding on to my four-wheel disability rollator, I invariably glance through the open door of the bathroom. It’s become a pattern. Glancing through the door at the metallic frame that holds my raised plastic disability toilet seat. This momentary experience reminds me of the times in my life when I’ve walked past specialist disability shops, gazing absently at all the unlikely paraphernalia from other people’s lives. This world of experience in one shop. And this is what it feels like, seeing this contraption installed around my toilet. It’s other people’s lives; not my own. But each time I remember that it is mine, and that’s quite shocking.

I think I feel the same level of original shock on every occasion. And these are largely the same feelings that I have about every disability item I own: the cone-shaped device for putting on my socks, the grabbing and reaching implements, the rails, the splint, the stroller, Dr Seuss’s fantastical self-washing wires and brushes. New items arrive almost daily and I am unexpectedly becoming the curator of the Museum of my own Decline. How did this happen? Because it wasn’t so long ago that I was walking past these shops. I was on the pavement looking in. And now I am inside.

*

If you’re disabled, London beggars don’t ask you for money. They don’t even make eye contact. I discovered this whilst visiting the UK at Christmas, travelling through London on my own. This was a few months before we had to move back permanently, and I was being disabled all by myself. I must have seemed quite unsteady because it was my first experience as the recipient of help from strangers. I found this exciting. I don’t feel excitement any more. But at that time it was exhilarating in the way that all transportive experiences can be exhilarating. Like an acting student with a begging bowl or a celebrity in a fat suit. Except that it was me. The most complete version of me that I would ever be.

I changed trains at East Croydon and deliberately trailed a woman with a crutch who had a spastic leg like mine. I sat quite near her but realized she was much younger, with MS. Then I felt like an older man stalking a younger woman, which I briefly was. I gravitate towards people with a bad leg like me. At Three Bridges station there was a man of about my age with an even slower walk than me. He was dressed smartly and clearly trying to sustain some kind of job. I was coming from the other direction and had enough time to become excited by the way his leg was swaying wildly – just like mine. It was rush hour. Not an easy time to be thrashing your leg around. I wanted to wave or to say something; or communicate to my brother with an upward turn of my eyebrows. And because we were heading in opposite directions I knew our unacknowledged time together would be fleeting. He needed help, from crutches at least, but he had nothing. I was impressed by his lack of speed. I should have been going a little slower. Or I should have stopped to think, but I ended up doing the opposite. I picked up speed and felt momentarily jaunty. It’s what I must have wanted. I was racing along. And that was it; the moment for connection was gone.

He’s not the first person I’ve picked out, wondering whether he or she is the same as me. Wanting to ask. I fabricated a notion that this man’s symptoms might have been further on than mine. Perhaps he had been slow to refer himself, and was soldiering on. A man who was continuing to work in the face of considerable difficulty – wondering why his foot wouldn’t lift off the ground. Wondering why he was always toppling over like an old wet tree in the rain. And waiting for it all to stop, for the body to return, to heal, because that is what the body does.

I don’t think I’m looking for my comrades any more. Not with quite that expectation. Or with that sense of shocking newness I want to share. But still, when I’m with a friendly physio or occupational therapist, I often end up asking about their other patients. I must want to find someone like me. Someone out there with children who is where I am with this disease. Someone out there who is writing about it. Wanting it to be OK. Willing it to be OK. I want to meet this person.

*

It’s shocking to me that I have a spastic leg. I’m struck by its arcing trajectory, its banana-shaped inefficiency, and by the sticks I use to compensate for it. And by the wheelchair I will one day be consigned to, the toileting aids that await me, disfigurement, the premature ageing. These are all shocking to me; I’m calm about it, but still shocked. I’m calmly shocked.

All my life I’ve convinced myself that I have a remarkably striking physical appearance. Unfortunately, I have been capable of believing that almost anything about me, or almost anything I’ve done, might be remarkably brilliant. I have been afflicted by this delusion for my entire life. There’s nothing unusual about this. It’s just the dreariness of narcissism. Only the route towards narcissism is unique. The real stuff. The narcissism itself, the affliction, is dull, boring and predictable. And as with all narcissism, mine has an obverse side which is equally true and equally present: the unrelenting conviction that when I’m not being remarkably clever and beautiful, I’m being remarkably stupid and ugly.

But now I’m living with a concept that is neither. It’s not life at the end of either of these two extremes. It’s not even on the same linear scale. These days I’m preoccupied by the surprises in my life. The way the body reminds me of myself. The saliva I’m now collecting in my mouth. It’s this. It’s all the tiny signals I experience. The not swallowing. The lagoons beneath my tongue. These pools of saliva don’t interest the narcissist in me. In the presence of such novel details I’ve finally found a way to bore him. With my actual body. The volumes of swallowed juices that sluice away like the downpipe from a toilet stack. Sometimes when I inhale they inadvertently skim backwards with a splutter and a choke. Or, if I’m lying on my front, a small amount disappears over the curve of my bottom lip. Just a little for now, over the side of the bed. Just a tiny stream from a toy teapot. A darkened dot on the carpet. Everything starts as something small. There are no shocks. This is a gentle kind of devastation.

When I was a much younger man I spent a year or so not being narcissistic. I had found God, briefly. I knew him for a year. He loved me and I loved him and my narcissism ebbed away. I felt the tension in my body release. I felt my 25-year-old body open up, after many years of tightness. When I no longer felt I knew him, my narcissism returned. My body closed again, as if a season had passed. This sounds glib, but it’s the truth. And even though I lost hold of what I had found, I don’t think a person ever completely loses what they have had. I’d lived with a level of shock and confusion my entire life, but something had been lifted that was never completely pushed back down again.

And now, being a man with a spastic leg, finding myself being wheeled through an airport in a wheelchair, as I was earlier today, I realize this is the culmination. It’s finishing something, finally and decisively. I’m a man with a disability. My body is the truth now and it’s saving me from myself. I have all these losses, and feel a kind of freedom in that. With each awkward, spasmodic movement, or the difficulty I have wiping my own bottom, or with the slur developing in my voice, the narcissist recedes. There’s nothing for him here. Not any more. It’s death to him. The phoney.

You wasted a lot of my life. Nothing you did was ever real.

*

In the weeks and months that followed my diagnosis I received dozens of suggestions about how I might combat my decline. Some fell into the category of tonic and these included several exotic examples, such as a paste made from mixing water with powdered scrapings from reindeer-horn velvet. I was also advised to start my day with warming spices, so that I might have a ginger or a cinnamon tea. Or I could have eggs for breakfast and cook them with turmeric and cumin.

Other suggestions have been less to do with ingestion than the functions or processes that I could add or alter within my body. In one of the loveliest examples a friend espoused the medical benefits that singing could offer me. A more prosaic example was that I could slow the progression of the disease by chewing my food more slowly.

In some cases, these suggestions have been delivered with little confidence. Perhaps they’re offered if a person feels awkward and wants to think of something positive to say – so that it might be something they’d heard about from someone or caught as a snippet on the radio. On one occasion I received a text from a friend to inform me that a new drugs trial in India had yielded miraculous results. I texted back to ask for more details but, unfortunately, he was unable to be more specific. I wondered if he might have the name of a town or medical institution so that I could narrow it down a little but, no, it was just something that was happening broadly within the nation of India.

Others have been far more confident in their approaches – strikingly so. I’m particularly thinking of two parents from Tom’s previous school in Portugal. In both cases, I didn’t know the people involved that well and they had first learnt of my condition from chatting to another parent in the playground. In the case of these two women it was interesting to note some common attributes to their communication style. Both times the initial engagement involved gently touching my elbow and very sensitively, very earnestly, leading me away from a mingled group of parents. What I then noticed was the closeness of the physical space they occupied, so that the intensity of the eye contact lent the exchange a certain gravity and seriousness.

As for the suggestions themselves, they were both to do with diet. I have noticed that people can be at their most fervent when making claims that this or that diet can combat my decline. I group these two approaches together because each person espoused a dietary regime which, as far as I can tell, appeared to be the diametric opposite of the other. So that one of them was suggesting a diet based exclusively on fats and animal protein, whilst the other suggested a vegetarian diet of brown rice, sea vegetables and pulses.

As these two separate discussions continued, and the volume of parents surrounding us thinned significantly, it became clear that these two women weren’t actually prescribing a bespoke cure for my specific neurological condition; in fact, it wasn’t entirely clear that they knew what my condition was. It didn’t appear to be the case that the diets could specifically prevent my motor neurones dying. Instead I was offered the reassurance that they themselves, and their family – as notably healthy and flourishing individuals – were also following this dietary regime and that anyone else in their right mind should be doing the same. As time went on, and we met repeatedly in the playground – and it became clear that I wasn’t following their guidance – the looks on their faces conveyed a saintly form of disappointment. I had been offered the way but clearly lacked piety. In this respect, it seemed that I hadn’t been approached by two friendly and knowledgeable parents but by two variants of the same religion.

The list of cures I receive continues to grow. It seems important for some people to feel that they can do something about what’s happening to me. Sometimes this is offered in a caring or despairing way and sometimes it’s evangelical. But in all cases it feels like a frustration with the idea that things happen: the idea that we all might grow old or that any of us might contract an illness or a disease and not be able to do anything about it, or the idea that none of us really possess control over our lives. For many people this is clearly unbearable and intolerable, so that just being is frightening – and that the only possible sane response is to be doing something.

*

The loss of motor neurones begins with a display – something visible just beneath the surface of the skin. You could watch my wrist and observe tiny pulsing movements working their way up my arm – like a trapped cricket trying to find its way out. Or if you were to place an open hand on the side of my neck, you might wait there for a moment and then suddenly squeak or let out a little ‘Ooh!’ as you snatch your hand away.

These are the flickerings of a light bulb before the plink and fizz of a blown filament. Tiny faltering premonitions of loss – a kind of panic or disturbance in a muscle that is losing its sense of purpose within the body. For some reason, these twitches make me think of earthworms after the rain – when the soil is claggy and they come to the surface for oxygen: the way they blindly pop out of the soil, flailing and wriggling in the unnatural habitat of the air.

When I hold Gill’s hand the sensation transmits through the ends of my fingers or through the muscle at the base of my thumb. It’s hard to feel her flinching from the movements of my body – from the subcutaneous crickets and the earthworms popping up for air. Hard to reassure her that at least the fibres are still looking for connection – that they haven’t given up – that it’s not the end.

But these fasciculations are beginning to get less frequent now – like that moment at the end of a garden fireworks display when the nostrils are pleasingly filled with sulphur and the last firework in the box fizzles out and someone hands you a sausage roll, and you’re standing by the embers of the bonfire watching the ghost of an image from a burnt-out sparkler.

*

A couple of times in the writing of this book I’ve discarded more extended metaphors that attempted to convey what this disease is – and its effect on the body. In the first, I was describing a steel suspension bridge: the way the bridge appears to function normally, whilst up above, and out of view of the traffic, the cables supporting the stanchions are snapping one by one. Over time, fewer of the cables are taking more of the strain until, finally, a steel stanchion begins to creak and wobble. From this point, decay continues much as it did before but now visible and obvious.

The second of my abandoned metaphors employed the image of a corner shop, in which shelf items mysteriously disappear through the walls or the floor. Increasingly, the stock appears sporadic and the shop becomes less useful as a place for anyone to reliably buy their groceries. Sometimes the shop door opens and the visitor looks around, having arrived here through habit, forgetting that the place has fallen into decline. Others still choose to come, if they have the time, remembering what it was – or they maintain their shopping habit out of nostalgia and affection.

It’s so easy to reach for these metaphors of loss and decay, and I think this has something to do with the absence of concrete information about what this disease actually is, or what causes it. No one appears to know why or how or when motor neurones die within the body; why the line of communication between brain and muscular tissue breaks down. It remains a mystery, so that in thinking and writing about my degenerating body, imagery and imagination can be everything. This is the reason why, despite writing about the removal of extended metaphors, I’m nonetheless tripping over smaller, rat-size examples of imagery darting in from every angle.

But when reaching too far into metaphor, the experience of what something actually feels like becomes lost – and because I feel this experience so profoundly within my body, it’s description that really matters to me. I’ve had my moment here – descending into metaphor – to help explain the little I know about how this disease works. But I don’t experience the disease, I experience my body, and this is what interests me. I know enough not to think that sea vegetables or reindeer velvet can delay its course. Of course, somewhere out there, a reason exists for why these neurones die, and there’s probably something out there that will stop this. Maybe it is sea vegetables! But these dart-throwing investigations can’t be anything to do with me – not whilst the shamans are still shaking their sticks at the moon. They don’t interest me.

All that interests me is being with people – and with my body as it dies – and writing about it.

*

On the other side of the room Tom and Jimmy are flapping on our bed like unnetted herrings on the deck of a trawler. Gill’s laughing and the boys are squealing, but I’m over here with my recliner all the way back resting my tongue on the floor of my mouth. It’s unusual to be this much on the outside of an escapade, not even to be enjoying the fact that my children are so happy. I could be in an adjacent hotel room or in a split time frame. There are other moments when I will sit and enjoy: laughing or smiling at acrobatics, or boofing a pillow into someone’s face. But on this occasion my recliner is tilted back and I’m interested in the difference between the roofs of the two terraced houses I can see through the window. The slate on one roof is clean and new, but where the roof becomes another property the roofer has left the moss-barnacled slates unchanged. It’s the same roof. A shared roof. But the two parts are cared for as if they exist in different continents.

Gill and I can still talk and talk when we get the chance, and I can still read books to the boys, but this evening my facial and tongue muscles have grown more tired than usual. I spent the day on the phone to estate agents, solicitors and various health professionals. I became hoarse quite early on in the day and then the susceptible muscle at the base of my tongue began to ache. I used my reserves and now I’m spent. So I’ve tilted myself back in this moment and taken myself away. To a time, perhaps a year from now, when the voice is gone and the face is gone. And my hands can no longer make signs. Preparing for disability is like going on holiday somewhere new and wondering what clothes to pack. For now, I’m scouting it out. Just temporarily – just for an hour or two. Being elsewhere, in an expanding private world; a world I will get to know. I’m glad to feel it first. Preparing for when I will be looking out at the life of my family. Knowing that I was out there once. The clown. The protagonist. The herring.

In the moments before Doctor Tiago called me in, I was propping up a wall with my shoulder. When you spend a lot of time in hospitals being undiagnosed, you start propping up walls and lounging about and picking your nose in waiting rooms. And not being prepared for certainty when it comes.

An hour or two before, Doctor Tiago had been scratching away at my body with a pin. But before all this, I’d been lying on my front and waiting. I could hear him scrabbling about, trying to find something. I heard the clasp of his bag. I heard him stirring the contents around. The thin metallic sound of a cabinet door being opened and shut. A drawer sliding open and then slamming shut. He’d been searching in the room for something sharp. I realized that later. I don’t know where he got the pin from. Thinking about it, I was lying face down: it might not have been a pin. What was it? This wasn’t the first time he’d taken to me with something sharp. He’d made some preliminary etchings on my last visit, but this time he was dragging the pin rapidly across and around my back and legs in wide swirling motions; an impressionist holding their brush at the very tip of the handle, standing back from their canvas and operating in broad strokes. He’d stop for a moment and then start again. Then he’d have another thought and drag the pin wildly in a different direction. And when I sat up he was holding his chin and thinking.

‘Your face is lopsided.’

‘Is it?’

I really like Doctor Tiago. His smile is perhaps the broadest and most expressive smile I have ever encountered. It is so broad and all-encompassing that it seems to subsume his entire face, right up to his eyebrows. A couple of months earlier he had found me wandering the corridors, having arrived at the hospital for a non-existent appointment. He seemed much more like a very young and enthusiastic uncle than a doctor. On that occasion he set up an impromptu clinic in what seemed like a stationery cupboard and we went from there. In all my time with the hospital, I was never really aware of how appointments happened. They just did. It was all quite miraculous. And so I don’t mind that he put so much effort into trying to find a brain tumour. He was clearly misled by my face. Even the neurologist who did my CAT scan said I had a brain tumour. They couldn’t find any evidence of a tumour. This didn’t matter. They remained convinced. Cheerfully so. Apparently a brain tumour is great news.

I wonder why it is important to know. It always seems so very important, particularly for doctors. But surely they seldom know. Or they seldom really know. Doctor Tiago ‘knew’ I had a brain tumour within five minutes of meeting me. But this wasn’t knowing; this was confidence. We’d have had a better conversation without confidence getting in the way. There’s so much to simply not know about the body. I’d prefer a person who really knows about something (like Doctor Tiago) to tell me all the myriad fascinating things they don’t know. Because however much a person knows about something, that knowing is minuscule compared to what they don’t know. A scale demonstration of this would involve standing next to a mountain and pouring a kilo bag of sugar on the ground. Standing back and comparing these two mounds would give the onlooker a visual comparison between the little that is known about anything by anyone (the sugar) and the vastness of what is unknown about everything by everyone (the mountain). None of us know. Even the most knowledgeable amongst us don’t know. Doctor Tiago didn’t know. I’d like to have spent more time with Doctor Tiago not knowing.