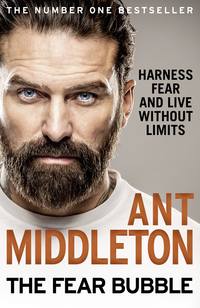

The Fear Bubble: Harness Fear and Live Without Limits

When my mind gets bombarded with questions like this, I always like to take a step back and ask myself the most important question of all. Who am I? I’m someone that loves a challenge. I will challenge absolutely everything. I love opportunity. I will seize every one that comes my way until the end. But my main characteristic is that I love putting myself into situations where I’m forced to sink or swim. I want fear bubbles in my life. I want to be in a world in which I’m having to step into them and pop them in order to move forwards. Everything about this offer scared me. In which case, perhaps I should give it a try.

As it turned out, stepping out of the shadows was indeed a difficult thing to do. After I was approached about the show, I was put under immense pressure from everyone up to Director Special Forces himself not to take part. I was called in for a meeting and told that I would be in breach of my contract if I did it. I didn’t believe this was fair.

‘You’re not paying to put food on my table or a roof over my head, but you still want to dictate the terms of my life,’ I said. ‘You expect me to live in the shadows even when you’re not looking after me any more.’

In that moment I made up my mind. I wasn’t going to let them dictate to me.

‘I’m doing it. Take me to court.’

I soon discovered that I wasn’t the only former operator to tip up as a presenter on the show who’d been through similar meetings and also possessed the fortitude to press on.

The truth is, if I hadn’t had my particular relationship with fear, I would never have called that posh guy back. But I did, and it changed everything. Because that’s what happens when you live with courage. When my phone rang on that sunny morning in Sierra Leone, it felt as if a door had appeared before me. In front of that door was a fear bubble. After a lot of anxious thinking, I decided to step into that bubble and open that door. And when I went through it, I found myself in a brand new world.

This is all of human life. We live our days in a corridor that’s lined with doors. Each one of those doors is frightening to open. This is why, nine times out of ten, we choose to step back from them, leaving them closed. But whenever we muster the courage to step through them, we emerge into a new and better corridor, one that’s lined with even more doors that are even scarier to open. Becoming the person we want to be, with the life we’ve always dreamed of living, is simply a matter of developing the courage to open more doors.

You might not believe that a radical transformation in yourself could be this easy. But it really is. Trust me when I tell you there are two lives you could be living. There’s the life you’re in right now, at this moment, and there’s the better life that’s just a step away. Every day that passes without you getting to grips with harnessing your fear means another day that these doors remain shut and you stay limited. I want you to start changing this today. I want you to begin opening these doors. And not only am I going to tell you exactly how to do it, I’m going to show you that it’s much easier than you think.

I also want to impress upon you that this should be an urgent mission. You should take it seriously. The sad thing about all these doors you’ve left closed in your life so far is that you’ve no idea what lay behind them. You can’t imagine who you’d be today if you’d been just a little bit more courageous over the years. But that’s enough looking back. I don’t want to make you feel regretful or negative. As you’ll soon discover, an essential component of the fear bubble technique is the positive mindset. Simply know that your days stuck in that same corridor you’ve been in for years are now numbered.

WELCOME TO THE FEAR BUBBLE

As you read this book, I want to tell you the story of my journey up Mount Everest. It was during those long days in the spring of 2018, a great many of which were spent quietly putting one foot in front of the other, that much of the thinking you’ll find in these pages was done. After that, I want to tell you the story of my coming down Everest, which ultimately turned into the most fearful and humbling experience of my life. But most importantly, I want to use my adventures, encounters and conversations on that mountain as a springboard to dive into everything I’ve learned over the years about how the ability to harness fear and use its power can enable anyone to live without limits.

I’m going to explore how damaging fear can actually be to the individual and everyone around them if it’s not contained. Living in fear is corrosive. It creates negativity that spreads throughout a whole life and actually changes the way you perceive reality. Just as it did twenty years ago on Snowdon for the lad just above me who became terrified and suddenly saw the mountain as one huge death trap, fear makes the entire world seem threatening, dangerous and populated by aggressors. This is why living in fear creates a victim mindset – a mindset that’s spreading like wildfire in today’s society, creating a generation of men and women who seem motivated only to stamp their feet and hope that everyone else will take responsibility for them.

I’ll then take a deep look into the three kinds of fear: fear of suffering, fear of failure and fear of conflict. I’ll explain how exactly the same fear underlies all of these – the fear that you’re not good enough. If you can learn to harness this one – and you can – there will be absolutely no stopping you.

If you’ve read my previous book, you’ll already be familiar with the finer details of my life. After the death of my beloved father, I endured a tough childhood in France with a new stepfather and a mother who forbade any of her children to mourn. I joined the army at seventeen, crashed out at twenty-one, went through a dark period of alcohol abuse, steroid abuse and street violence before finding direction, structure and passion in the Marines, with whom I served a tour of duty in Helmand Province in Afghanistan, and then as an elite operator in the Special Boat Service for four years. When I returned to civvy street in 2011, an altercation with a police officer led me to prison, where I served four months of a fourteen-month sentence for assault. After my release I worked in a variety of jobs that can be very loosely bracketed under the term ‘security’. And then I received the call from that posh man from the TV.

But, as I said, if you’ve read First Man In you’ll know all this already. The pages you hold in your hands now contain a very different piece of work. That book was my story. This book is my soul.

CHAPTER 3

THE ROAD TO CHOMOLUNGMA

2 April 2017. Qatar Airways Flight 648 from Doha to Tribhuvan International Airport in the Kathmandu Valley. Two hours and twelve minutes until we’d land. A stranger to the left of me, a stranger to the right of me. Perfect. I loved flying alone. The stress of everyday life just melted away, with the white noise of the engines making me feel like I was back in the womb, safe and warm, but with a smiling stewardess bringing me cold cans of beer. I was determined to enjoy the solitude and anonymity while I could. But it wouldn’t last long. Because, since I’d cleared this trip with Emilie six months ago, there had been a significant change of plan.

It had happened during a meeting with a TV executive, a couple of weeks after that morning in the kitchen. I’d arrived to discuss the filming of the next two series of SAS: Who Dares Wins, which were going to be filmed somewhere in South America.

‘We’re going to need you guys for a good six weeks,’ said the commissioning editor. ‘It may even be a couple of months. I guess it depends on how much preparation needs doing and the extent to which you want to get involved in the fine details this time, Ant.’

‘I’ll want to be involved from the beginning, as always,’ I said, reaching for my phone and its calendar app so I could check my dates. ‘But I can’t do anything April, May time because I’m away.’

‘For the whole two months?’ he asked.

‘Yes, mate,’ I said. ‘I’m going up Everest.’

He looked at me with an uncomfortable combination of alarm and insult. What was the matter with him?

‘That’s all right, isn’t it?’ I said. ‘I thought we were thinking later in the year for SAS anyway.’

‘Yeah, yeah, sure. It was just, I was wondering – who’s covering that, then? Everest?’

It took me a moment to realise what he was thinking.

‘What, filming it?’ I said. ‘Nobody’s covering it. It’s just a personal thing. I’m not doing a show about it.’

With that, his discomfort melted into glee.

‘Well, we should get someone out there with you.’

‘Mate, I appreciate the thought, but I don’t know about this one,’ I said. ‘It’s kind of a holiday for me. I don’t want it to turn into some big production. I just want to keep it small. Me and the mountain.’

‘Oh, but we can keep it small,’ he said. ‘That’s no problem. That’s easy. We’ll strap a fucking GoPro on your hat and send one other dude up there with you.’

‘What, up Everest?’ I said. ‘You can find a cameraman who can keep up, all the way to the summit?’

‘I think I can,’ he said. ‘In fact, I know I can. Ed Wardle. He’s been up there like three times or something.’

‘To the summit?’

‘To the summit. You’d like him. Scottish. He filmed something that was a bit similar to Mutiny a few years back. Shackleton’s journey. Ernest Shackleton. Is that right? I think that’s right. Ernest Shackleton. They went across the Southern Ocean in a little lifeboat using period gear. Proper hardcore. They were living off bowls of, like, cold fat.’

‘How far did they go?’ I asked.

‘Um, can’t remember. Something like 800 miles, I think.’

I looked down at my phone and began tapping at the volume buttons distractedly. ‘800 miles?’ I said. ‘He wants to try 4,000 miles.’

‘Think about it, Ant. Tell me you’ll think about it.’

‘Yeah, I will,’ I said. ‘I definitely will.’

I definitely wouldn’t. This wasn’t what I wanted at all. Part of the attraction of Mount Everest was that there were no rules up on the mountain. I could do what the hell I wanted, take as many risks as I needed to give me that edge I was seeking and generally get into as much trouble as I liked. Having a film crew there, even if it was just one guy, would ruin all that. I wanted to do this thing dangerously. I wasn’t going to take the easy route. Other people just didn’t understand my level of resilience. They didn’t know what I was capable of or what I’d experienced, and I didn’t want to be lumbered with well-meaning people, fussing about me, telling me what I could and couldn’t do.

In the run-up to Mutiny there had been endless pressure from Channel 4 and the production company to do things as sensibly as possible. They’d called all the shots on Health and Safety. I was determined that the trip across the Pacific would be absolutely authentic and fought them all the way on the endless restrictions they kept trying to force upon us. But there was only so much I could do. We ended up making small modifications to the boat and we had nine people compared with the eighteen that went on the original voyage along with Captain Bligh. We were as near as we could be to keeping it real, but I’d have preferred to have kept the things that they removed. The thought of all this nonsense happening to my Everest adventure was not a welcome one.

But then a few weeks passed. And I thought about it. And I kept on going back to the fact that there were five numerals, a comma and a little curly squiggle that made the offer pretty much impossible to refuse. £60,000. The only thing about this trip that had given me reason to doubt its wisdom was the mad cost of it. I was willing to spend the money because I knew that was what it took. But I also had my family to think about. It was a serious amount of cash, and if I could use it for my wife and kids rather than me, and have to sacrifice a little freedom on the mountain to make it happen, then that felt like a trade I simply had to make. If someone else was actually willing to pick up the bill, I felt like I’d have to say yes.

But that compromise soon led to another compromise, one that I was pretty unhappy about. The channel, and the production company, insisted that I book the trip through a different expedition firm. While the track record of Elite Himalayan Adventures was impeccable, they were still quite a young outfit and the terms of the expensive TV insurance they’d have had to take out dictated that we use people experienced with the particular demands of a film crew. That meant a group called Madison Mountaineering, based in Seattle, Washington and founded by Garrett Madison, who bills himself as ‘America’s premier Everest climber and guide’ and has garnered a reputation for taking the ‘ultra-wealthy’ up to the summit, with luxury trips that cost as much as $120,000. This sounded, to an uncanny extent, like exactly what I didn’t want.

Just three days before my flight to Kathmandu I’d come off the final date of my speaking tour. I’d been travelling the country for six weeks, taking my one-man show to theatres from Torquay to Leicester, Cardiff to Manchester, where I was lucky enough to have an audience of 2,500. It had been unbelievably good fun, getting out there and meeting people and hearing their stories, and I’d become so absorbed in the experience that when my departure date from Heathrow came along, it did so suddenly. To say I wasn’t mentally prepared for the trip would be an understatement. My head was in a completely different universe, still buzzing from the tour. The idea of going up the highest mountain in the world, in potentially deadly conditions, was one I hadn’t even begun getting my head around.

If anything, my physical preparedness was even worse. I’d been eating badly for a month and a half, drinking half a bottle of wine every night and living mainly off chicken wings from the twenty-four-hour room service of the hotels I’d been staying in. I had a lingering memory of Gareth, my tour manager, knocking on my door one night and with a troubled look on his face asking, ‘How’s the training for Everest going?’ I’d picked up my large glass of red wine and toasted him merrily – ‘Don’t you worry about me.’

On Everest there had been one fatality for every sixteenth person to have successfully climbed it. But I liked those odds. As I lay back on the pillows of my huge hotel bed, in my warm, fluffy hotel dressing-gown, licking Buffalo sauce off my fingertips in preparation for another sip of my nice Shiraz, one in sixteen didn’t seem like anything to worry about at all.

And then, on a dull and rainy English spring morning, I found myself packing my luggage into the back of a taxi and going through the ritual of kissing my family goodbye. As I slammed the boot of the cab shut, my two-year-old daughter Priseïs, clinging on to her favourite pink mouse-ear backpack, suddenly burst into tears as she registered that Daddy was going away somewhere for a long time.

‘I know, I know, I know, baby,’ I said. But I couldn’t calm her.

As my car swung out of the centre of Chelmsford I switched on the little camera that I’d been given to film my journey and pointed it at my face. ‘It’s never nice saying goodbye. I’m just going to dwell on it for a couple of minutes. Get it out of my system and then get my head in the game.’

I turned the thing off and looked out at the wet trees and the grey motorway. I was close to tears.

But by the time I was pushing up my tray table to prepare for the landing at Kathmandu’s Tribhuvan International, that familiar bittersweet sadness was long gone. I was about to alight in a brand new country, one of my most favourite little pleasures. There’s not much else that can fill me with such simple childish delight as the sight of an airport sign spelled out in an unfamiliar alphabet.

When I’m in a foreign land it always feels as if the chains have been taken off, especially these days, when it’s becoming increasingly hard for me to move about unnoticed. Stepping off the plane in my grey T-shirt and jeans, I could feel the drop in temperature and sense the thin air. A fizz of enthusiasm bubbled up as I walked through the brick building, past adverts for the Everest Bank, and hustled my way impatiently through immigration and then customs. I entered the noisy arrivals hall, weaving my trolley laden with my three bags of kit past endless leather-jacketed men calling, ‘Taxi, taxi, do you need a taxi?’, and was met by a fixer from Madison Mountaineering, who was holding a little board with my name on.

‘Welcome to Kathmandu, Ant!’

Part of the deal for agreeing to have my expedition filmed was that I wasn’t going to do it in the luxury style at which Madison, in particular, excelled. Any normal commercial expedition up Everest involves a large team of people led by Western guides and supported by teams of local Sherpas, who all work with between ten and twenty clients at any one time. As you’d expect, these companies can and do ply their trade with safety as a top priority. One of the biggest dangers on Everest concerns the many problems that come as a result of the lack of available oxygen. This is not just an issue in the death zone. People can fall sick, become confused and make perilously bad decisions even down at Base Camp, which sits at over 5,000 metres above sea level, where there’s 50 per cent less oxygen in the air than in the lowlands.

To try to combat this, Westerners are taken up the hill slowly. When you’re ascending from sea level to nearly the cruising altitude of a jumbo jet, you need to allow your body to become used to the conditions as gradually as possible. This is why climbers use a system of ‘rotations’ to acclimatise. Having first done the long trek to Base Camp, where they can stay for two weeks or more, the rotations start with the ascent from there to Camp I, where they stay for two nights. Then it’s a couple of nights in Camp II and then back down to Base Camp again. The second rotation is the same, with the addition of Camp III. It’s pretty standard to complete a third rotation. And then, finally, you get to do the summit rotation.

That sounded like a lot of hassle to me. I didn’t think I could be bothered to complete three rotations only to have to start all over again from Base Camp to get to the top. I decided I’d see how I felt when I got on the mountain, but I honestly didn’t feel the need to be as careful as all the other Westerners. I wasn’t there for my health and safety.

And there were also some other ways in which I intended to do my climb differently to most. I made it clear to Madison Mountaineering that, as far as possible, I’d be my own boss. While they would take care of all the general organisation, and I’d stay in their camps and make use of their supplies of food, drink and oxygen, I wasn’t going to be chucked in with all their wealthy clients. I didn’t want to be part of any tour group. I also refused the help of their Western guides. My expedition was just going to be me, a Sherpa, Ed to film us and another Sherpa for him. And unlike all the other fresh-faced visitors, I wasn’t going to rely on Sherpas to lug my stuff up the hill. Westerners are sometimes guilty of viewing the locals as little more than mules – I wasn’t going to be one of them, and I would carry my own kit.

‘Your Sherpa’s outside waiting to meet you,’ said Madison’s American fixer, trying to take my trolley off me so she could push it. ‘His name is Dawa Lama. And your cameraman Ed’s here too.’

‘Thank you,’ I said, politely but insistently pulling my trolley back.

As soon as I left the airport building I clocked Ed. He was walking towards me with his large camera held at chest height and his headset on. I’d heard that this tall Scottish hard-man was an alpha, and he certainly appeared to be a very capable individual. He was six foot five, lightly grizzled and looked to be in his forties. He was fit and lean in his untucked shirt, black trousers and hiking boots. I realised it was important that our relationship struck the right balance from the outset. I knew, from sore experience, that having two alphas working closely together could be difficult, and it usually requires some precise handling. A couple of days earlier he’d called me so we could make our final arrangements to meet and begin the process of getting to know each other. When I answered the phone, he said, ‘I’m on Ben Nevis.’ Obviously it was necessary that he called, but why do it from the highest mountain in Britain unless you’re making a point? He seemed like a decent and smart guy when we chatted, but that phone call had put me on slight alert. I thought, ‘Let’s see how this pans out.’

Although I was happy to meet Ed in the flesh, as soon as I saw his camera pointing at me I felt my heart sink. It wasn’t the fact of the camera itself, it was all the attention that being filmed naturally draws towards you. You become instantly highlighted. Lines of blue-uniformed policemen stared at us, as did all the porters, drivers and tourists who were milling about the busy airport parkway. I could see them squinting at me thinking, ‘Who in the hell’s that?’ It was a sudden reminder of the compromise I’d made in allowing this thing to be filmed. If I’d arrived alone, as planned, I’d have been feeling utterly free and joyful right about now.

As I approached the smiling Scotsman, I had to give myself a little pep talk: ‘This is my thing. He’s following me up a mountain. I’m not going to let him take my trip over and turn it into a “show”.’ I made a promise to myself. My attitude towards Ed was always going to be, ‘Follow me. If you get your footage, you get it. If you don’t, you don’t.’

‘How you doing, mate?’ I said, shaking his hand. ‘You good?’

‘Yes, mate,’ he said. He fixed me with a slightly quizzical look. ‘Do you realise what you’ve got yourself into?’

That got my guard up. In his own subtle way it seemed that Ed was instantly questioning my ability. The skill set involved in being a member of the Special Forces is a lot different to what’s needed by an elite mountaineer, and he knew it. Not only that, but since our chat on the phone the other day he knew I’d only ever been as high as 6,100 metres above sea level. That’s pretty high, but it’s not Everest. The whole situation threatened to put me on the back foot immediately. I could tell that Ed was extremely sure of himself and didn’t take any shit. He’d be an easy guy to get on with if he respected you, but he didn’t suffer fools. Quiet worries crowded in on me: ‘Am I going to have to live up to his standards? Am I going to have to follow him up to the summit?’

Although he was probably acting subconsciously, I couldn’t ignore the fact that he was trying to assert himself as the leader from the start. While I knew it wasn’t a personal thing – it’s just what alphas do – I also knew I had to turn it around. And quickly. It would have been the easiest thing in the world to have stepped back and let him take the reins. It would even have made logical sense, given that he was by far the more experienced mountaineer. But I wasn’t going to allow Ed to make the decisions. I couldn’t ever have a situation in which he was telling me, ‘Well, Ant, there’s a bit of wind today so we best go tomorrow.’ A bit of wind? Good. All the more reason to go now. This trip was mine and I was doing it for my own reasons. They’d jumped on my bandwagon, not the other way round.

And then, out from behind Ed, as if by magic, appeared the man who would be my Sherpa. Dawa Lama had been picked especially for me by Madison and I was a bit shocked when I saw him. I’m only small myself, but Dawa was positively tiny. Not only was he five foot nothing in height, he had a bit of weight on him. I’d imagined someone a bit more trim and a lot taller. Was this really the man who’d be leading me up the world’s most deadly mountain? But he had to be capable, I told myself. He wouldn’t have been selected if he wasn’t. The only way we were going to find out what he was made of was by getting him up on that hill.