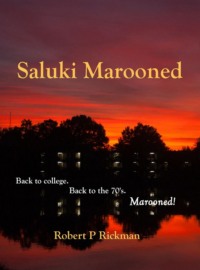

Saluki Marooned

When I stood up, the blood drained from my head, leaving a thick sludge that weighted my head so that I was looking down at my feet. The sludge shifted ponderously around as I reeled to the exit door, slipped on the wet train steps, and landed in a heap on the ground.

Welcome to Carbondale!

With the help of a lamppost, I pulled myself to my feet and stood swaying like a bottom-heavy blow-up clown, then stumbled out onto the sidewalk and started a shambling walk down Illinois Avenue—the main drag—until I reached a coffee shop. The ache in my shoulder reminded me of last year’s brawl at Demonic Grounds, and I didn’t need a visit from the gremlins, so I chose to stay outside and behave myself. Yet I hung around the shop’s entrance, curious to see what modern SIU students looked like.

At first glance, they didn’t look much different than my generation did in the early ‘70s. Except: A kid walked in the door with a tastefully camouflaged backpack fitted with compartments for his laptop, cell phone, iPod, and one of those blessed water bottle-things we never had in the ‘70s. In the Vietnam era, students wore Army surplus backpacks with something like a peace symbol sewn raggedly on the flap.

The door to the shop edged open and a coed (Do they call them that anymore?) left the shop while awkwardly balancing three cups of coffee in her hands in an effort to avoid spilling them on her Versace jeans. When I attended SIU, I walked around in beat-to-hell combat boots, and our “designer” jeans were stiff-as-a-board bellbottoms that took a month of washings to soften up. Fashion-conscious students tie-dyed the jeans in the bathtub, then wore them until they fell apart—and no one gave a damn what was spilled on them.

Inside the shop, a petite girl sitting with a swimming pool-sized cup of coffee was sporting a short, razor-cut hairstyle, dyed the SIU colors—maroon with white streaks—and the guy sitting across from her had the same hairstyle, but in brown. In the ‘70s, our hair wasn’t “styled.” We either cut it ourselves or went to an old-fashioned barber and hoped he didn’t cut off too much. We wore our hair stacked on our heads like leaves of lettuce piled in a salad bowl or splayed out in all directions like frazzled steel wool pads. And no one thought of dyeing his or her hair maroon, pink, or any other color, because we wanted it to look “natural.” Besides, SIU students of the early ‘70s didn’t have that much school spirit, and except for an occasional school sweatshirt, we didn’t wear maroon and white.

I noticed a youth sitting on a paisley cushion and playing a guitar, who looked like he had been teleported there from 1971. The kid affected a scraggily beard and wore a torn T-shirt, dirty jeans, and scuffed combat boots. But the outfit looked too perfect, as if he had seen an old photo of a genuine hippie on the Internet and had practiced dressing like him. I suspected that behind the façade lurked a squeaky-clean college student, circa 2009.

But I did notice a hint of genuine rebellion in this coffee shop crowd, because students wore glasses with larger lenses than what most people wore in 2009, probably because small lenses were “in” for everyone else, which meant they were “out” for college students. But, aside from this mild ophthalmological revolt, the rebellious look of the ‘70s was no longer rebellious—it had been studied and refined until it was the standard for the 21st-century student.

Two guys tried to exit the shop at the same time and got stuck in the door.

“Sorry,” said one guy.

“Excuse me,” said the other.

Such politeness! In the ‘70s this place would probably have been a bar, the two students probably would have been drunk and stoned, and their abrupt meeting would probably have led to a fight.

Yet there was something particular to SIU that stretched across the generations. A few students almost furtively came through the door of the coffee shop, slumped over, and sat down with sheepish looks, as if they had been beaten into submission by the very act of attending Southern and felt they didn’t deserve to be in such a nice place as this one. I remembered the “Saluki slump”—Harry, my roommate, slumped liked that every time he entered our dorm room. But his was an arrogant slump, as if to say, “I’m here, no big deal, unless you want to make something of it.”

I stood outside the coffee shop window, staring at this terrarium of student culture, and the students stared right back at me, as if mesmerized by a poisonous snake. I could see why, because my reflection in the shop window showed two demonic eyes staring a thousand yards into the distance, with the red pupils almost indistinguishable from the bloody whites. It was a face that was anything but normal. I looked down, saw the footprints of an impossibly big dog painted on the sidewalk, and followed them south.

Just ahead was Pizza King. PK’s never served pizza while I lived in Carbondale, but I drank a lot of beer there, and the suds were flowing that night. However, across the street, the Golden Gauntlet nightclub was now a pet store.

Sad.

I sensed there was more missing, a lot more, but I didn’t see it immediately, so I stared down the street until it came to me.

The Strip is gone!

The Purple Mouse Trap, Das Fass, Jim’s, Bonaparte’s Retreat, the Golden Gauntlet and The Club were all missing. All of the bars along the southernmost three blocks of South Illinois Avenue had transmogrified into nice-looking, nearly upscale bicycle stores, donut shops, fast food restaurants, and places like the one I was standing in front of. The display window showcased several life-size dolls that resembled greyhounds with long floppy ears. The Saluki dolls were sitting in a circle of maroon and white megaphones, looking up in admiration at a female mannequin that was wearing absolutely nothing, not even hair.

Salukis and maroon and white in business windows meant the merchants now had school spirit, which was different from my time, when business owners rarely hung anything in their windows that reminded them of SIU. The conservative Southern Illinoisans frowned on student riots and impromptu street parties downtown. And they looked askance at the bombing of the Agriculture Building in 1968, the burning of Old Main in 1969, and the closing of the university during the spring riots of 1970. What a difference forty years had made: Carbondale had gone from a jumble of low-rent businesses to an average, respectable university town: clean, orderly…and boring.

Yet there was one thing that separated Carbondale from other college towns, and that was size. The population had been 25,000, more or less, for decades, which made it a small town. On the other hand, SIU, to the south, had a maximum enrollment of 24,000 students, which made it the 24th largest university in the country in 1970. Very few huge institutions like SIU are located in isolated small towns, thirteen miles from the closest interstate, in a world of their own.

I leaned against a lamppost and studied the photo of Catherine while squeezing, twisting, and wrenching the CPU in my head in an attempt to release another kilobyte of memory from the past. But I came up with nothing. Any image of the past was overlaid by what was right in front of my eyes in the present. I was the same person, and Carbondale was the same town, but both of us had moved ahead on the timeline and could never return to the ‘70s.

I walked past the Varsity Theater, which was vacant with a FOR SALE sign in the window and newspapers blowing around the doorway. I passed the old Dairy Queen, which was dark except for the big ice cream cone on the roof with its bright little lights. I continued south until I reached an old house that had been converted into a bar back in 1971. Redwood stain was peeling off the former 1910 American Tap, rocks were missing from the cement wall enclosing the beer garden, and FOR SALE signs decorated both front windows. American Tap looked like an old man who had lost his lower front teeth.

But, oddly, a pipe with a curved stem was smoldering in an ashtray on a table in the window. The aroma of the burning tobacco seemed to come from far away. I felt as if my body was in the 21st century, but my sense of smell was somewhere else.

I followed the giant Saluki paw prints to the entrance of Southern Illinois University Carbondale and stepped on campus for the first time in twenty years. A light rain fell from the low clouds making the original one-square-block campus look like it had been built in a vast cavern. Wheeler Hall, with its ghastly blood-red brick, rose behind a gothic wrought iron fence, and in front of Davies Gymnasium, the old girls’ gym, a little boy stood holding an umbrella over a little girl.

Still there!

Paul and Virginia had been placidly standing on the island of a small fountain for more than a century, but tonight, the bronze faces of the two children looked cold and emotionless. I walked to the west, beyond the dismal statue, past the bust of a frowning Delyte Morris—placed where the halls of Old Main used to cross—and past the mausoleum-like Shryock Auditorium to the location of the brutal, concrete Faner Hall.

But Faner wasn’t there. I edged my way closer, and my knee bumped with a crack into a giant reel of wire. As I rubbed the bruise, I looked around and saw stacks of pipe and wire mesh, work trucks, and wooden planks lying in mud, bordered by deep trenches. I guessed a new building was going up, but where was Faner? The thing had been started in 1970 and finished in 1975, after being expanded to include classroom space that had been lost when Old Main was torched. Faner had been longer than the Titanic.

Maybe they tore it down, but why?

Suddenly, from the east, I heard shouts and dozens of feet running towards me from the direction of the overpass that stretched across Highway 51. It sounded like a live broadcast of a riot from a distant a.m. radio station, fading in and out.

My comfortable alma mater was starting to creep me out. The heebie-jeebies began buzzing in my chest as I quickly sought refuge in Thompson Woods, behind where Faner should have been. The woods were reeking with the odors of wet moss, leaves, wood, pot, tear gas, fear, and sweat. As I wandered in darkness, branches seemed to deliberately bar my way along the slick asphalt paths, and slippery leaves muffled my footsteps. Many of the trees were lying on the ground; others were split or missing limbs. The woods looked ghastly.

I broke out of the trees and into a swirling fog behind the Agriculture Building. A siren sounded in the distance, and as it got closer, the pitch lowered, but the volume increased to an ear-splitting scream, and an SIU police car careened into view. It looked as if it was going to miss the curve and crash into the trees ahead—but it faded away. And it didn’t drive off into the distance, either. No, it faded into invisibility, and I felt the physical sensation of fading along with it, though I was standing rigid with fear at the crosswalk.

Oh, Jesus.

I was hallucinating. Yet my mind was as lucid as a diamond. I reached in my pocket for the pill container and threw it into the street, where it broke open, and all of the colored pills bounced into the mist. By now, my head was congested, my ears were filled with fluid, and all I wanted to do was turn around, walk back to the train station, and return to Chicago. But I knew what I would face on the return trip: a riot, the ghost of brutal Faner Hall, pensive Paul and Virginia, and that pipe in the ashtray in the window of the American Tap.

I crossed the street and walked into the woods around Campus Lake toward a picnic shelter I remembered. As I got closer to the shelter, I saw a woman in a long dress lying on her back on one of the picnic tables, but her form dissolved into a shadow as I walked past. Beyond the shelter, I spotted the geometric roof of the campus dock, trudged my way to it, and stood at the flagpole in front of the boat shelter while I wound my pocket watch. It was 6:34

I didn’t care whether it was day or night, because now I was entering the time frame where my body had finished metabolizing the drugs and alcohol, leaving only the miserable dregs of aches, pains, confusion and profound depression. As I clung to the flagpole, I felt as if I were rushing toward the lake.

I inhaled the muggy air, and those little chemical gremlins in my nervous system polluted it with such profound melancholy that when I exhaled, my face was inundated in a miasma of gloom. My head was filled with boiling oil that splashed against the back of my eyes every time my heart pounded. The fulminating oil emptied into my throat, ripped down my esophagus, and hit my stomach with a splash of corrosive acid. I gagged, but the corrosion only got so far as my throat, and I started coughing and hacking phlegm. My right rotator cuff was attached to my shoulder with a nail, and down below, my hips and flat feet throbbed in agony. But my eyes hurt most of all: that cottony silver light forced the corrosive oil into the backs of them, until everything I saw was tinged with red. I tried to squint in an attempt to cut the glare, but my eyelids fluttered involuntarily and were threatening to close. The fog shifted a little, briefly revealing the Thompson Point residence halls.

The dorms looked like how I felt: washed out, colorless, joyless. The engineering buildings behind me were mere phantoms in the fog, and the trees in the woods looked as if they were sketched in pen and ink against the swirling gray mist, their reflections etched in water the color of gun metal. Many of the trees were broken and jagged, lying half in the water near the dock and across the lake on Thompson Point.

My God, there is absolutely no color to anything!

A cold, gray drizzle swirled around me, and I felt the gray of the ground pass through the soles of my shoes and up into my head until my feelings turned dark gray. Boiling oil in the rotator cuff, boiling oil in the feet, the hands, and the neck. Boiling oil in the cough.

This was worst day of my pallid 58-year-long life.

The police car I’d seen earlier came rushing back from the opposite direction on Lincoln Drive, and screeched to a halt. The big, boxy cruiser looked like it had been built forty years ago, but it appeared to be in mint condition. I could see the shadow of the policeman behind the wheel reach down and turn on the siren. The noise sounded as if the damned thing was going off inside my damned head.

The siren blew for at least a minute—60 seconds of audio spikes stabbing my ears. When I turned my head away from the siren, the broken black-and-white trees started rushing past me, and I felt as if I was flying a jet fighter at Mach 1 through the woods.

And that did it.

With catastrophic finality, the broken woods, Tammy, Testing Unlimited!, Bob, my trailer, the vodka, the pills and the gremlins came down on me like a piano and pushed me to my knees so forcefully that indentations were cast in the sod.

I was kneeling next to a rack of canoes with my hands over my ears when the siren stopped. I crumpled to the ground, rolled under the canoes, and passed out.

I was awakened by the mechanical pencil digging into my chest; the soldier on the train must have slipped it in my shirt pocket while I slept. As I rolled out from under the canoes, I was blinded by a bright morning sun reflecting off the lake. I stood up slowly, and was surprised at how I felt, considering the previous night’s bender. I had no headache, no nausea; the minor pains in my feet and back were gone, and so was the chronic ache in my rotator cuff. My eyesight had sharpened, so that I noticed the individual leaves on the Kodachrome green trees. The light blue roof of the boathouse pleasantly complimented the azure sky shimmering in the blue water of the lake. My sense of smell had intensified as well, so I felt awash in pleasant odors: blooming flowers, damp grass, and water gently lapping over the mud near the shore. I could hear the chirp of the crickets, which sounded higher pitched and more musical than they used to. The temperature must have been in the upper 70’s—not too hot, not to cold—and I felt all of these sensations with a passion that I scarcely remembered.

But what happened to fall?

It also seemed that the trees, dock, grass and lake were slightly out of place. Either that or I was.

As I walked over to a picnic table in front of the dock shelter, a bright green grasshopper jumped past me, and I felt as if I weighed only fifty pounds. Past the flagpole, the redwood trim on the Thompson Point residence halls glowed in the sun. But there was something off kilter with TP as well. It was there, right in plain sight, but it took a minute or so for me to realize that the trees around the buildings had been repaired: there were no broken branches, none of the trees were laying in the water, and none of them were split, yet they were shorter than they should have been considering that The Point was fifty years old.

I started a fast walk through the trees near the dock and was soon striding on the path along the edge of the lake, past the picnic shelter with its geodesic dome—which was white. Last night it had been brown. I felt the gremlins clustering at the base of my spine, waiting for one more weird revelation to start their attack. So I rationalized that maybe I’d been so messed up on drugs the night before that I couldn’t tell brown from white. I quickened my pace, and walked over a little wire and wood bridge that crossed a small rivulet behind a residence hall. My senses were high, probing everywhere as I reached the sidewalk between the dorm and the Lentz Hall commons unit—which didn’t look new, but it didn’t look half a century old, either.

Just leaving Lentz was a familiar figure of a girl—familiar as an old statue, even though it’s been decades since you last saw it. Her honey blond hair was down to her waist, and an apricot shift with big flowers clung to her immature figure, revealing skinny legs with a soft blond down glistening in the sun. The figure waived at me.

“Hey, Peter!” she yelled.

The girl was not so much walking as gliding down the sidewalk with a deportment that indicated that as far as she was concerned, anything that was going on in the world at this moment was about as okay as it could be, and that the moon, the stars, and all of the planets were in their proper order, as her horoscope for the day revealed.

When the girl was 50 feet from me, her vaguely familiar figure became chillingly real. It looked like Marta, the woman who had sent me the letters that past summer.

But that’s impossible!

The girl was wearing rose-colored sunglasses and a big hat that threatened to flop over her face. As unreal as it was, I felt as if I were the only person on the planet. And when she got within five feet of me, it was as if I’d been pulled into a bubble of infinite wellbeing. A strong scent of saffron incense clung to her clothes.

“Peter, how are you?” she asked in a way that would imply that I was the most important person in the world, and meeting me was the single most important event in her life. Furthermore, the “are” carried an additional connotation: that regardless of how I responded or how I felt, everything was indeed okay with me.

“Are, are you…you look like…Marta?”

“Yes, I’m Marta!” she chirped proudly.

“What…but you look... what brings you here?”

The girl gave me a sideways look. “You mean right now?”

“Yes, right now!”

“I came to check the mail.”

“What!? I mean what are you doing on this campus?”

The girl looked at me as if I were nuts.

“Going to school, just like you… and, I’m late for class.” She looked serious for just a moment.

“I’m not going to school! Now come on, what are you doing here?”

I was terrified. She cocked her head, as if appraising my mood.

“OK…you caught me...” Marta confessed. “I’m not really going to college. I’m actually from the planet Neptune. We’re here to study you earthlings. And might I say you dudes are really weird…particularly you...” She laughed. “Peter, you need to loosen up, man!”

With a giggle and a wave, Marta started walking toward the Agriculture Building.

“See you at lunch,” she said over her shoulder.

This can’t be!

Even though her hat and sunglasses had covered most of her face, it looked like Marta hadn’t aged a day since I had last seen her, nearly four decades ago!

As I stared in shock at the girl’s retreating figure, I noticed old, boxy cars passing behind her along Lincoln Drive. I snapped my head around, and saw that old, boxy cars were parked in the lot near Lentz and along Point Drive as well. I ran up the drive, and found vehicles that I hadn’t seen in such good condition for years: a 1970 Impala, a 1966 Fury, a 1965 Mustang. And every one of them had Illinois license plates dated 1971.

Suddenly the Point exploded with students. Many wore Tshirts; others sported dress shirts with all of the buttons fastened or none of the buttons fastened. There were Army field jackets, denim jackets, and an occasional sport coat. The kids wore corduroy trousers or bell bottom jeans cinched with big, wide belts. And it was all unisex; there were no skirts. The students carried their books at their sides, or wore Army surplus backpacks. Their hair was long and styled in bangs, or split down the middle so that it cascaded down either side of the face.

Several of these children looked vaguely familiar.

My eyes frantically snapped from the students to the cars, to the cafeteria, to the trees and lake—looking for anything that would tell me I was still in the 21st Century.

I reached into my trousers for the pocket watch, but it was gone, and in its place was a chain with the SIU crest attached to it, along with a single key with a sticker displaying the number 108. I was standing in front of a three-story brick and concrete building in all of its mid-20th century glory, with brushed steel letters on the side wall that spelled BAILEY HALL. The redwood slats over the casement windows looked like they had been freshly stained, and glass bricks made the stairwell windows shine in the sun. This was home during my sophomore year at SIU.

I looked neither left nor right, because I was afraid I might see anything from a charging rhinoceros to Richard Nixon. I walked up to the entrance and tried the key…and the door opened. It felt as if the SIU police were about to come down on me at any minute as I ducked furtively inside a hazily familiar hall. In a trance, I walked up to 108, stuck the key in the door, gingerly pushed it open, and was enveloped in the smell of stale tobacco and whiskey. The front half of the room was neat as a pin: the bed was made and all of the books were meticulously lined up on a shelf at the bottom of a blond wood desk. Nearby was a coffee pot and a hotplate, sitting on top of a log standing on its end. As I passed the mirror above the sink, I saw the reflection of a skinny student, and turned around to address the kid, but there was no one there. I turned back to the mirror and saw the reflection of the kid again. I whirled around: there was no one else in the room. I snapped back to the mirror, and facing me was that kid with an agitated expression on his face. He looked the way I felt, except he was fifty pounds lighter and almost forty years younger and wore this ridiculous mustache and…

His eyes widened like saucers. I jerked away from the mirror as if I had seen a ghost, and faced the window overlooking Point Drive. Below it was another blond wood desk, buried in books and papers. Against the wall and facing the sink was an unmade bed with a distantly familiar dark red bedspread that I had forgotten about long ago. And next to it was a nightstand with a fake-walnut-covered clock radio, just like the one that had been stolen from me at a youth hostel I had stayed at in San Diego during a drunken binge in 1981, when I was homeless.

My mind started spinning with the realization that I was reliving in rich detail what had been only minutes ago an indistinct memory. If all of this was a hallucination, I was in deep trouble, and if it wasn’t, I was in even deeper trouble. I gingerly stepped over to the mirror and risked another quick glance at the kid, followed by a longer glance, and yet another, and still another, until I was staring at him. What I saw was not just the image of a 20-year-old youth.