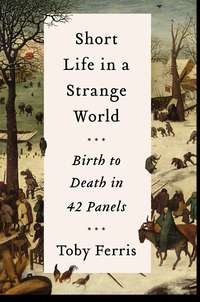

Short Life in a Strange World: Birth to Death in 42 Panels

Yes, there it is: to stand in front of Dulle Griet is to experience a noteworthy percept, of ruddiness.

Perhaps painters in the sixteenth century – who had been apprenticed to other painters from a young age, grinding and mixing paints, staring at bowls and pastes and palettes of saturated colour morning to night, lost dreamy adolescents there in the workshop reeking of glues and sizes, while outside the world was passing through a duller, less superficial age, an age of few images and no industrial dyes – perhaps sixteenth-century painters, in short, were more sensitive to the allure of pure pigment.

The ruddy sky is all the ruddier for the silhouetted city, the rigging and towers and cavorting creatures picked out in front of it. The charred blackness brings out the red.

In particular there is a tower with a rigged flagpole: frogs, or frog-like entities, are climbing the rigging; a monkey watches from the tower. And one of the frogs is dancing a victory jig as the horizon burns. He is waving a spear. Elsewhere, more frog entities are dancing a round-dance on a tiered structure.

A burning city was not the most unusual sight in the sixteenth century: it was something to which the imagination, if not the eye, would have been accustomed.

In 1534, Bruegel’s putative hometown of Breda burned to the ground. Of 3,000 buildings, only 150 remained.

Such was the periodic fate of medieval cities, wooden towns. Like the forests renewed by wildfire, so too cities were regularly reduced by fire escaped from hearth or furnace or set (in the popular imagination) by conspiratorial arsonists communicating by means of secret signs placed on buildings. Come running with a bucket if you must, but this is how cities clear their undergrowth.

This ruddiness was the colour to fear in the sixteenth century.

‘The burning of forest began settlement,’ says Stephen J. Pyne in his history of European fire regimes, Vestal Fire: ‘the burning of cities ended it.’

On 14th May 1940, following a breakdown of communication (signal flares lost in the smoke of battle while the Dutch negotiated surrender), the Luftwaffe bombed Rotterdam. Some planes turned back, but a remnant fleet of fifty-seven low-flying Heinkel He 111s dropped 1,150 110lb and 158 550lb bombs on the Dutch forces holding the north bank of the Nieuwe Maas River. The wooden city burned for two days, the fires fuelled not only by the buildings but by tanks of vegetable oil located near the old port. An estimated 850 people died, and 85,000 were rendered homeless; 24,978 homes, 24 churches, 2,320 stores, 775 warehouses and 62 schools were destroyed.

On the day following the raid, British Bomber Command was instructed to alter its directives on so-called strategic bombing, and begin targeting cities of the Ruhr, including their civilian populations. The era of firestorms – Hamburg, Dresden, Tokyo – had begun.

Rotterdam would be bombed again, multiple times, over the next four years, by Allied forces. The city was no longer as combustible as it had been on 14th May 1940, but other forms of destruction were available.

*

‘When the invasion of Holland took place, I was recalled from leave and went on my first operation on 15th May 1940 against mainland Germany. Our target was Dortmund and on the way back we were routed via Rotterdam. The German Air Force had bombed Rotterdam the day before and it was still in flames. I realized then only too well that the phoney war was over and that this was for real. By that time the fire services had extinguished a number of fires, but they were still dotted around the whole city. This was the first time I’d ever seen devastation by fires on this scale. We went right over the southern outskirts of Rotterdam at about 6,000 or 7,000 feet, and you could actually smell the smoke from the fires burning on the ground. I was shocked seeing a city in flames like that. Devastation on a scale I had never experienced.’

Air Commodore Wilf Burnett, DSO

*

To make a painting is to hope that it will last. But none lasts for ever. Any singular object is a hostage to looting, theft, earthquake, fire, flood, bombing, and other local versions of the apocalypse. The post-war map of Europe, as of much of the globe, was excoriated, flattened, pounded to ashes; millions died and much was destroyed.

The Bruegel Object, so far as we know, was untouched. The paintings were smuggled underground, into mines and tunnels; when they re-emerged, they were unwrapped and dusted down and rehung, icons of resurrection. The yawning gaps in civilization crusted over, and on we went.

But it is only a matter of time and accident. When will the last Bruegel painting disappear? They are fragile. Which one will it be? And what about records of his paintings, his existence? Will his name vanish along with the last painting, or will he, some Apelles of a forgotten history, a forgotten Europe, persist as myth, the JPEGs flickering out on servers one by one, corrupt unreadable binary representations of long-forgotten cult objects?

One week before our Antwerp visit I get word that Anna Keen’s Amsterdam studio and home has burned to the ground. The shed next to hers, the one with the yachts or speedboats, caught fire around breakfast time; both it and Anna’s shed were flammable subsystems, wood and canvas and paper and gallons of volatile chemicals, boats and easels, sailcloth and packets of economy food. The whole lot went up in a plume of blue smoke so high it made the local TV news.

Anna got out in her pyjamas but lost everything else. Her studio was a workshop and a home for much of her life. In Rome, she would pick through skips for furniture, curiosities, would sketch endlessly with thick black soft charcoals and snub-nosed pencils and sometimes in pen and wash.

And now it was all gone. All her paints and painting equipment, unsold paintings and work in progress, rolls of canvas, stretchers, a lifetime’s sketchbooks, her library, her computer, her clothes, her documents, her electrostats (as she called them) and amplifier. Everything except her pyjamas, her bicycle and a small wooden dinghy she had bought in Venice. Nothing was insured. She had pressing debts, no income, and was several months pregnant with the child of a man who might or might not intend to stay around.

The next morning, she was out in the biblical wreckage of her life, sketching the twisted forms, picking over corners of vanished books, documenting the carnage. What else can you do? Habit will see you through.

I speak to Anna on the phone and suggest she come down to Antwerp, or meet us in Bruges or Brussels. Or we could come up to Amsterdam. But she has appointments to replace her passport and deal with legal problems of rent and deposits.

So I am in Antwerp, alone, waiting for my brother. Next to Dulle Griet hangs Twelve Proverbs, an early work, essentially twelve separate representations of proverbs in roundels, set within one frame on which the relevant proverbs (My endeavours are in vain; I piss at the moon – Ill-tempered and surly am I, I bang my head against the wall – I hide under a blue cloak, the more I conceal the more I reveal – He whose work is for nothing casts pearls before swine) are inscribed. There is a marbled decorative element and the backgrounds to the figures are a uniform red. The handwriting of the inscriptions dates the assembly to between 1560 and 1580.

It is, in fact, a set of apotheosized placemats. It was a popular format. Teljoorschilders, or plate-painters, were recognized as distinct craftsmen in the Antwerp painters’ guild between 1570 and 1610. Their plate-format paintings were usually set off against red backgrounds and had diameters of roughly 20 centimetres. They came in sets of six or twelve or twenty-four. Proverbs were an appropriate adornment, connected as they were with domestic wisdom.

A search for Bruegel proverb-placemats on Google throws up nothing. A missed opportunity, for someone.

What do you do in front of such an object (assuming you are not eating your dinner off it) if not read each proverb in turn, moving from the wall-plaque to the painting and back again?

Bruegel thought in proverbs. The proverb had pedigree as a rational device, formalized in Erasmus’s collection of adages, first published in 1500 and added to, revised, expanded for the next three decades. By the end of his life, Erasmus had collected 4,151 proverbs and adages and dicta, a list parodied by Rabelais’s parallel version in Gargantua of (mostly scatological) proverbs and mirrored by countless other collections through the sixteenth century.

We like to think we have left proverbs behind. We demonstrate our intelligence by sharply differentiating ourselves, picking out the anomalous, the noteworthy, the untoward in the world around us; we hunt out the discrepancy on the untidy fringes of knowledge because it is here that we will locate the telling detail, pull at the loose thread, which will in turn explode the commonplace that threatens to engulf us. ‘Insignificance is the locus of true significance,’ said Roland Barthes; ‘this should never be forgotten.’

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.

Вы ознакомились с фрагментом книги.

Для бесплатного чтения открыта только часть текста.

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера:

Всего 10 форматов