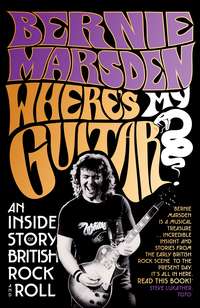

Where’s My Guitar?: An Inside Story of British Rock and Roll

I astonished my folks one evening when I was able to play along with the theme tunes from Coronation Street and Dixon of Dock Green. They were both very enthusiastic but I told them that, even though I had improved, the guitar was holding me back. I thought my heavy hint was a bit of a long shot but to my delight they agreed. Thank you, TV theme writers!

I saved every penny from my paper round, and had been saving all my birthday and Christmas money for a couple of years. I had enough money for a deposit! Dad said he would help me out as much as he could. ‘How do we get an electric guitar?’ he said. I knew exactly where. I had been there before.

3.

Look Through Any Window

When I was 13 I spent a few days in at my aunt Doreen’s house in Hampstead, London. I was allowed to make a bus trip on my own after promising I would see the town but not get off the bus.

I boarded the no. 24 from Hampstead to Pimlico, a round trip of about three hours. It remains a great way to see central London. I sat in the prime seat – front, upstairs – and went to Camden Town, Marylebone Road, Gower Street, Trafalgar Square into Whitehall. Sitting there all alone I saw Nelson’s Column, the Houses of Parliament, Big Ben, Westminster Abbey and more, all sights I had only seen in pictures or TV. It was very exciting.

On the return leg I glanced up at 114 Charing Cross Road, the Selmer Music Store – the UK’s sole importer of American guitars. It was a life-changing moment. I had promised not to leave the bus, but what could I do? I had seen Selmer’s window, full of Fender, Gibson, and Epiphone guitars. It was fate. If I had been sitting on the left-hand side of that bus, I would never have noticed. I was down those bus stairs and off the footplate without thinking.

There were bass guitars, amplifiers, and custom-coloured Strats that I’d only ever seen in catalogues. The archtop Gibsons in the store were almost two hundred pounds, an unreal amount of money. One side of the store stocked brass instruments with the famous Selmer badge on them, all very well but of no interest to me, really, the guitars had me totally spellbound. Selmer’s was a magic kingdom. The Beatles had been in this very store, as had the Hollies and the Applejacks.

I spent over two hours in the shop but it took me an hour before I actually plucked up the courage to touch one. The assistants were very nice and I took a Fender Stratocaster down from the wall and dared to ask how much it was. The answer was 140 guineas, the equivalent of around £165. This was an incredible amount of money. That very same model today would be worth £30,000 or more.

It eventually dawned that my aunt and uncle would be wondering where the hell I was as I’d been gone for three hours longer than expected – oops. I apologised, told them where I had been and promised not to do it again.

The next day I was on the twenty-four again, this time getting off at Cambridge Circus. I walked up Charing Cross Road and to my delight I discovered many more guitar shops – Macari’s, Pan Music. I returned to Selmer’s where I heard a famous band were also browsing – could it be John, Paul, or George, or maybe Tony Hicks or Graham Nash? No, it was just the Bachelors, brothers Con and Dec Cluskey buying new Gibson acoustics. The Bachelors were one of my mum’s favourites.

It wasn’t until later visits that I met the Merseybeats, also Chris Curtis, the drummer with the Searchers. I had taken a guitar from the wall, totally out of my price range, of course, and was playing it quietly. Curtis said I was a very good player and invited me to his flat in Chelsea. I accepted his invitation – he was a pop star, after all, and had a chauffeur-driven car. I still don’t believe it, but I got in the car with a man I had just met. With hindsight, that could have been a terrible scenario.

He said that he would cook at the flat. Jon Lord later told me that he was probably elsewhere in the flat at the time – Jon was ten years older than me and was just then starting the project with Chris that would later become Deep Purple. As it turned out, there were only Cornflakes in Chelsea and so that was the meal. I did feel a little strange, eating cereal with Mr Curtis, and wondering why I was there. I should also say that Chris was very nice to me, and nothing whatsoever questionable happened. Maybe he had in mind that I could have been the guitarist for Roundabout, but I was only a young teenager. Jon would later pull my leg about that day, especially at breakfast in a hotel on the road where there were Cornflakes around.

I got to know Denmark Street’s shops well and when my dad asked me where we could get an electric guitar, I was ready. Dad was the guarantor for the hire purchase agreement. Selmer had a special offer on the Colorama 2 by the German company Hofner, whose guitars were very popular, reasonably priced and good quality. It was the one for me. The monthly repayments were quite high, but I really didn’t care: and I had my first electric guitar!

I held the green plastic case tightly as we went home. I thought the guitar was beautiful. It was finished in a cream colour, had twin pickups and a tremolo arm. I took it everywhere – my mum often said that I was chained to it. I couldn’t believe how much easier it was to play than my Spanish acoustic. There was just one more thing …

‘You never said anything about a bloody amplifier!’ said my dad.

I pleaded with him and we acquired a five-watt Dallas amp from Butler’s furniture shop in Buckingham. I practised daily and our next-door neighbour, Tom Tranter, who worked nights, soon had his own name for my setup. He called it ‘That bloody electric thing.’

I quickly improved at the guitar while my grades at school plummeted (although I did get a B-plus for music). The art teacher said in his year report, ‘I have never known such an idle and yet so charming boy.’ I rather liked that.

The first real group I was in was the Jokers: I must have been about 14. They were already an established act with Eric Jeffs on bass, Stan Church on drums, Dave Brock (not the future Hawkwind leader!) as the vocalist and second guitarist, and Steve Rooney the lead guitarist. Eric played bass guitar left-handed, à la McCartney – but strung normally and played upside down.

In the practice room at the youth club I immediately realised the underpowered Dallas was useless in this company. I knew I needed a bigger amp but I didn’t have any money, and asking Dad was out of the question. Guitarist Steve owned a six-input amplifier with a massive thirty watts of power which I used via Dave. Steve found me – a young upstart – playing all the guitar licks he knew plus quite a few that he didn’t and, worse still, playing them through his massive amp. Having both of us in the band was never going to work. The upstart 14-year-old was already shining brighter than Steve and he left the band – and took the big amp with him. Dave Brock had a lovely, blue Watkins Dominator amp which he lent me. I wish I still had it, a very collectable amplifier.

Steve later told me he left the band because he wanted to spend more time with his girlfriend. I was amazed. Even at 14, I couldn’t understand why anybody would want to spend time with a girl instead of being the guitarist in the Jokers.

I was very keen, practising all the time, learning Chuck Berry riffs and Bo Diddley songs, and I settled in very quickly. We had a major upset when drummer Stan Church left after a member of his family was jailed for the manslaughter of a local girl. The case even made national TV. I was very young and quite frankly confused. I didn’t understand why this had to have such an impact on my band – was having the name Church the reason?

Roger Hollis replaced Stan as our drummer. He lived near me in Overn Avenue, and was an early heavy metal drummer: he really did hit them hard. We practised every Tuesday and Thursday evening, when the sound of the judo lessons in the upper room was louder than the band. Amps were soon to become a lot louder – thank you, Jim Marshall.

We had another setback when there was a robbery and all of the Jokers’ equipment was stolen. The story made front page of the Buckingham Advertiser and they sent a photographer who asked us to look appropriately sad. I felt a bit of a fraud as the only equipment I owned was safely back at home: I would never, ever leave my guitar behind.

The Jokers ran out of steam and I came across the Originals, whose guitarist Nipper Rogers had been such an inspiration to me. On one Sunday afternoon I was playing acoustic guitar in the garden of the King’s Head. Originals’ singer Keith ‘Diver’ Fenables heard me playing, asked who I was, and then disappeared. He had gone to tell drummer Les Castle about this new kid playing the guitar. He casually asked me if I could play any of their songs and I said yes, I could.

‘Good,’ he smiled back at me. ‘Be here at seven tonight.’

It dawned on me that I had just signed myself up to a gig. Nipper Rogers’ job took him away from the area and the Originals couldn’t do any gigs – until this particular Sunday! I was petrified: not only had I only played their songs in my bedroom, but Nipper was streets ahead of me as a guitar player My mouth had said that I could do it and so now I would play in a pub packed with punters.

I arrived at the King’s Head at about six, very nervous, and a little panicked because I didn’t have an amplifier. Les Castle was setting up his drum kit and had a big smile.

‘Well, you are young, my boy,’ he said, pointing to Nipper’s Burns Orbit 3 amplifier. ‘Use that.’ Les, Keith and I played in a corner of the main bar without a bass player. I kept my head down to avoid making any eye contact with the audience. I was pleased not to hear any booing after the first few songs. Les Castle gave me another smile.

‘Fabulous, my boy, carry on like that!’

We played ‘I Can Tell’, ‘Shakin’ All Over’, ‘Green Green Grass of Home’, ‘Twist and Shout’, ‘Kansas City’, ‘Look Through Any Window’ and ‘Hoochie Coochie Man’. By this time Keith Fenables was also smiling.

Half an hour later it sank in – I was playing with the Originals. I dreaded to think how it sounded, but after a few songs I felt brave enough to glance at the crowd. They were looking happy and a little shell-shocked. Who the hell was this wonder kid? Where was Nipper, the one-and-only, local Hank Marvin? The audience got louder as the night went on, and everyone had a bloody good time. At the end of the night, Keith introduced me to the crowd: ‘Let’s hear it for the new kid on the cuh-tah, ladeez an’ genelmen!’

Keith was deliriously happy. Never again would Nipper Rogers dictate to the Originals: here was a readymade and impressionable new player they could call on, unencumbered by girlfriend or job. The position of my hero Nipper as the top dog was gone after one Sunday night in the King’s Head. I was the new kid in town. Nipper never once called me out for taking his gig. Not only that but he was the single influence among all the great guitarists who made me believe I could pick up a guitar. Thanks, Nipper.

The bonus that night was that I got paid! Thirty shillings, a pound note, a 10-bob note and a baguette sandwich to take home. I could sense things were about to change – this was a turning point for the very young BM. I was hired for the regular Sunday night Originals gigs and the Hofner Colorama paid for itself many times over. I practised hard, improving the guitar parts on the songs and gaining in confidence. All my earnings were put aside at home for a Fender Strat and amp, and my mum found the savings one afternoon. There must have been the best part of a hundred pounds, a hell of a wad for a teenager. She and Dad sat me down to ask where I’d got the money from. It was only fairly recently that my dad admitted they thought I might have been a robber. They never expected I was paid to play. My dad’s face lit up although dear old Mum seemed a little sceptical. I soon acquired my own Burns Orbit amplifier.

We played most weekends, mainly in pubs, working men’s clubs and at wedding receptions and I got my first taste of fame. I loved it. I became quite a draw at the King’s Head, a local guitar hero. People treated me slightly differently – most were positive, although a few were jealous and some were unable to accept that this young kid could play the guitar at all. Women who were years older than me loved to hang out with the band, regardless of their marital status. Some weekends I was invited to a female fan’s house for a drink. I got to know a lot of them and I must have been very different to their husbands who had to be at work the next morning, mainly because I had to be back at school.

By the time I was 15, I was in my room so much, playing guitar, that I had become a bit of a loner at school. I did have a few good mates: Richard Bernert, Steve Wheeler, Derek Knee and Mick Hodgkinson, but even then it was the common love of music that connected us. I’d often go to Richard’s and mime to the Small Faces’ first album he played at maximum volume in the living room. I was Steve Marriott, of course, and Richard was Kenney Jones knocking the crap out of a cake tin and cushions with a knife and fork.

Music also played a background role in a job I did with Derek and Richard. We worked for a local chicken farmer, feeding thousands of chickens, collecting eggs, and cleaning out the cages. It was pretty well-paid for the time. The henhouse was an inferno of squawking, but we had a very loud radio pumping out Radio Caroline or Radio London from an eight-inch Fane speaker. The first time I ever heard the Stones’ ‘Jumpin’ Jack Flash’ was on Radio Caroline. The opening line really grabbed my attention.

Pirate radio was so important. I got to hear fantastic records one after another, and maximum volume in the henhouse made them sound so much better. The radio reception was unpredictable: some days our area was good, but I was likely to lose the guitar solo just when I was ready to learn it!

I didn’t want to leave school at 15, so I stayed for another year, not knowing what I wanted to do in terms of a ‘proper’ job. The only clear path I had in my mind was something involving guitar. And, boy, was I playing a lot of it by the time I reached my final year …

At the start of the year there was mass excitement because of the arrival of a new 22-year-old French teacher, Elizabeth Rees. She was a great-looking girl, about five foot three, long, black hair, glasses on the end of her nose, short skirt and high-heeled shoes. I think she could tell she was near enough every schoolboy’s fantasy. She stopped me in the corridor to ask why I had opted to take history instead of French. As she smiled at me I asked myself the same question. She said that she would make sure I worked hard and I went to the school office and promptly dumped history. I never did learn much French, but she did teach me one hell of a lot about life.

Elizabeth had heard me playing with the Originals and said she was astonished by my playing and I would be famous one day. This was a revelation – she was the only forward-thinker in the school, heading for the Seventies with the same attitude as all the kids who were stumbling towards that decade of change.

Despite my passion for the guitar, music had never been a favourite lesson. I didn’t know or care what a stave was – tiny black squiggles on five straight lines did not seem like music – but I enjoyed the playing side. I remember one lesson I was playing to some girls when music teacher Mrs Gwen Clark arrived. I put the guitar down.

‘Don’t put that thing away just yet,’ she said with a hint of sarcasm. She passed me a handwritten sheet music. ‘So, can you play that?’

I looked at the paper – black squiggles on a stave. I couldn’t decipher it. She was making a point about my sight-reading ability.

‘Now listen and learn,’ she said. She played the first notes on the piano. I recognised the tune, the theme from Z Cars on TV. The girls in my class looked on. I picked up the guitar and played the Z Cars melody almost instantly, Mrs Clark was looking a little vexed. I then played the guitar intro to Chuck Berry’s ‘Johnny B. Goode’.

‘So, can you play that?’ I asked her. There were more than a few giggles. Mrs Clark was furious and, to contain her embarrassment, she left the room. I laughed, but she should have taken pleasure in seeing one of her own students playing this way, as an untrained natural. I am still irritated by the way that people with obvious talents were disregarded. If I had listened to my teachers I would never have left Buckingham, and never have tried to make it as a guitarist. It makes me wonder how many potential writers, musicians and artists there were in those dingy, soulless schoolrooms during the Sixties who were ridiculed for having such dreams.

I needed a practical music education. Enter my cousin John Keeley, three years older than me, who visited from Liverpool. He sang and played harmonica in a band, which impressed me a lot. I told him that I could play the guitar, which didn’t impress him, but he did listen to me playing along with recordings by Gerry and the Pacemakers and the Searchers, before instructing me to throw the records away. He told me to get LPs by Howling Wolf, Sonny Boy Williamson, Muddy Waters and Buddy Guy – but I did refuse to give up the Beatles. John had seen Williamson at the Cavern with the Yardbirds, and allowed me to keep my live Yardbirds LP featuring the young Eric Clapton. The blues hit me like a hurricane.

I became obsessed with all things Eric Clapton. I even bought Tuf town shoes because I read he wore them – I read any Clapton magazine article and I paid close attention to his influences. I soaked them all up – I was a musical sponge. If Clapton mentioned a player in an interview, I went straight down to the local shop to order that record. Some were so obscure, some on American labels with strange names: Chess, Federal, Sue and Pye International with the red-and-yellow labels. Artists such as Freddy King, Otis Rush, T. Bone Walker, and more. I slowed down the records to 16 rpm on the radiogram, making it a little easier to learn the guitar parts.

It wasn’t always straightforward to find this music. A folk guitarist first suggested I should listen to BB King. The folk player had a really good fingerstyle and liked the way I played, saying it was a very different approach. I was lucky to get a UK Ember label 45-record by mail order of ‘Rock Me Baby’, BB King’s great song. When that Ember record arrived, that was really it. I later found King’s UK Stateside releases, the European versions of the early BluesWay/ABC. Live at the Regal is the one liked by most guitarists, but for me it was Blues is King. Both were recorded in Chicago in the mid-1960s with a small band, and BB is on great form vocally and his guitar playing still motivates and inspires me.

If asked today, I might most often say that the music of The Beatles was the source of my musical career. But, if I am really honest, the blues music went on to inspire and motivate me most of my life. I had already been aware of Big Bill Broonzy, his name fascinated me, but I never really knew what blues music was. But, once I had heard the Yardbirds and John Mayall I was looking for their source material. I searched for BB King, Leadbelly, Big Bill, Brownie McGhee and Sonny Terry, which led me to Freddy and Albert King. I was given a Louisiana Red album when I was about 14 called Low Down Back Porch Blues. I liked it a lot, although I didn’t really understand what it was about.

At around that same age, I saw Lightnin’ Hopkins, Sister Rosetta Tharpe and Muddy Waters on TV. I was mesmerised. There is some quite phenomenal footage from 1964 of Rosetta Tharpe tearing it up with a white Gibson SG Custom at a railway station platform in Cheshire. It sounds crazy but it is a fact. Try and find it! This was the music I wanted to play. I bought a 45 of Howlin’ Wolf, ‘Smokestack Lightning’, which featured a fantastic guitar player on B-side ‘Goin’ Down Slow’– this was Hubert Sumlin. Hubert played with both of the great Chicago blues players, Muddy Waters and Howlin’ Wolf.

I was soaking up all this music. Gone were all my records of UK artists, even The Beatles and The Hollies were at the back of the pack when it came to the bluesmen. ‘Boogie Chillen’ by Hooker fascinated me, and still does. The guitar part is so weird, but I loved it and tried to play it. I didn’t know about capos or tunings then, but I loved the sound. I found that I could reproduce some of Sonny Boy’s harmonica parts on the guitar. That inspired me a lot. Just a tiny fraction of this music was developing my own style and, even though I was fully aware that Eric Clapton and Peter Green had already got it down, I did persevere.

When Cream themselves played Aylesbury in February 1967 there was nothing that would stop me seeing them. My pal Alan Clarke and I hitchhiked to a venue which was heaving with the largest number of people I had ever seen in one space. And then Cream were there: Jack Bruce, Ginger Baker, and ‘God’ himself, Clapton. Their Marshall amps towered on the small stage, Eric playing his Gibson SG Standard and I heard the ‘woman tone’ in person. I watched in a kind of dream state as they opened with ‘N. S. U.’, and played ‘Sleepy Time Time’, ‘Sweet Wine’, ‘Born Under a Bad Sign’, ‘Cat’s Squirrel’, and a devastating ‘I’m So Glad’. They were magnificent.

I was jolted into the real world in a surprising way. I felt a sharp prod in my back, and turned around to see Elizabeth Rees, the new French teacher. She was in a very good mood, looking really good, and had a definite twinkle in her eye. She straight away said she would take us back to Buckingham after the show. She was with a friend, a nasty little piece of work named Drew, who taught history. How pissed off Drew must have been to take us back on his date. Alan and I were just grateful not to walk back the sixteen miles.

Outside Buckingham town hall I thanked Drew for the lift, he eyed me with some contempt, and I got out of the car. To my surprise – and Drew’s shock – Elizabeth also said ‘Thanks’ and ‘Goodnight’ to him. Man, he must have been livid. Alan walked back home while Liz invited me back for a coffee at her flat in Well Street, a minute’s walk away.

I was still filled with the excitement of the Cream gig, until it slowly dawned on me that I was alone with my French teacher in her flat. She was calm and chatty, and we discussed the show and our musical interests: all very grown-up stuff. Liz had liked that I played ‘Hoochie Coochie Man’ at the pub. She went to her bedroom and came back with an album to play on her Dansette record player. It was The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan. I had never bothered with acoustic music, unless played by black musicians. The only folk music I was aware of was by the likes of Wally Whyton and the King Brothers on the radio show Family Favourites. Bob Dylan was so radical. I was quite stunned.

‘Listen to his words,’ she said. I still listen to them today.

She told me I could be like my heroes and that if I practised, worked hard and, above all, dedicated myself to being a musician I could make it a career. She pointed that neither Bob Dylan nor Eric Clapton had ever seen the inside of a university, and that the old USA blues players that I worshipped were lucky to get any schooling at all. I really listened to her. Academically, I was way behind, but in learning about life I was taking a huge step forward.

I spent a lot of time at school with Liz Rees, and rumours were rampant, particularly as my French was not improving. Liz was a bohemian free spirit, just the person a young lad of fifteen years of age should stay away from. I was infatuated, of course: she did exactly as she pleased and didn’t give a damn about authority.

Something had to give and, halfway through my fifth year, it did. I was called for a meeting with headmaster Gerald Banks. I expected a loud barrage of abuse, but he was very cool and professional. Mr Banks was a good man, and I now see how he turned out to be more of an influence than I realised. Miss Rees was not mentioned by name, but we both knew what the talk was about. He was astute enough to realise and could see that I was a very grown-up fifteen-year-old. I knew what I wanted and I think he knew I would get it. I had no fears about the future, exam results were of no real interest to me and I certainly didn’t give a toss about other people’s perception of my relationships.