Рефлексивные процессы и управление. Сборник материалов XI Международного симпозиума 16-17 октября 2017 г., Москва

1. Addo-Tenkorang, R., & Helo, P. T. (2016). Big data applications in operations/supply-chain management: A literature review. [Review]. Computers & Industrial Engineering, 101, 528–543. doi: 10.1016/j.cie.2016.09.023.

2. Akter, S., Wamba, S. F., Gunasekaran, A., Dubey, R., & Childe, S. J. (2016). How to improve firm performance using big data analytics capability and business strategy alignment? [Article]. International Journal of Production Economics, 182, 113–131. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpe.2016.08.018.

3. Argote, L., & Miron-Spektor, E. (2011). Organizational Learning: From Experience to Knowledge. [Article]. Organization Science, 22(5), 1123–1137. doi: 10.1287/orsc.1100.0621.

4. Ashby, W. R. (1964). An Introduction to Cybernetics. London: Methuen & Co Ltd.

5. Beer, S. (1979). The Heart of Enterprise. Chichester: Willey.

6. Beer, S. (1981). Brain of the Firm (2nd ed.). Chichester: Wiley.

7. Beer, S. (1985). Diagnosing the system for organisation. Chrichester: John Wiley.

8. Bello-Orgaz, G., Jung, J. J., & Camacho, D. (2016). Social big data: Recent achievements and new challenges. [Article]. Information Fusion, 28, 45–59. doi: 10.1016/j.inffus.2015.08.005

9. Bellomo, N., Clarke, D., Gibelli, L., Townsend, P., & Vreugdenhil, B. J. (2016). Human behaviours in evacuation crowd dynamics: From modelling to "big data" toward crisis management. [Review]. Physics of Life Reviews, 18, 1-21. doi: 10.1016/j.plrev.2016.05.014

10. Conant, R., & Ashby, W. R. (1970). Every good regulator of a system must be a model of that system. Intern. J. of Systems Science 1(2), 89–97.

11. Espejo, R. (1993). Management of Complexity in Problem Solving. In R. Espejo & M. Schwaninger (Eds.), Organizational Fitness: Corporate Effectiveness through management cybernetics (pp. 67–90). Frankfurt and New York: Campus Verlag.

12. Espejo, R., Bowling, D., & Hoverstadt, P. (1999). The viable system model and the Viplan software. [Article]. Kybernetes, 28(6–7), 661–678. doi: 10.1108/03684929910282944

13. Espejo, R., & Reyes, A. (2011). Organizational Systems: Managing Complexity with the Viable System Model. Heidelberg: Springer.

14. Espejo, R., Schuhmann, M., Schwaninger, M., & Bilello, H. (1996). Organizational Transformation and Learning. Chichester: Wiley.

15. Gupta, M., & George, J. F. (2016). Toward the development of a big data analytics capability. [Article]. Information & Management, 53(8), 1049–1064. doi: 10.1016/j.im.2016.07.004

16. Hashem, I. A. T., Yaqoob, I., Anuar, N. B., Mokhtar, S., Gani, A., & Khan, S. U. (2015). The rise of "big data" on cloud computing: Review and open research issues. [Article]. Information Systems, 47, 98-115. doi: 10.1016/j.is.2014.07.006

17. Kimball, R. (2002). The Data Warehouse Toolkit: The Complete Guide to Dimensional Modeling: Wiley.

18. Koskinen, K. U. (2012). Problem absorption as an organizational learning mechanism in project-based companies: Process thinking perspective. [Article]. International Journal of Project Management, 30(3), 308–316. doi: 10.1016/j.ijproman.2011.08.008

19. Maturana, H., & Varela, F. (1992). The Tree of Knowledge. Boston and London: Shambhala.

20. McAfee, A., & Brynjolfsson, E. (2012). STRATEGY & COMPETITION Big Data: The Management Revolution. [Article]. Harvard Business Review, 90(10), 60-+.

21. Perko. (2017). Behaviour-based short-term invoice probability of default evaluation. [Article]. European Journal of Operational Research, 257(3), 1045–1054. doi: 10.1016/j.ejor.2016.08.039

22. Perko, & Ototsky, P. (2016). Big Data for Business Ecosystem Players. 62(2), 12–24.

23. Perko, Primec, A., & Horvat, R. (2015). Sharing business partner behavior. [Article]. Kybernetes, 44(6–7), 1030–1048. doi: 10.1108/k-12-2014-0282.

24. Sivarajah, U., Kamal, M. M., Irani, Z., & Weerakkody, V. (2017). Critical analysis of Big Data challenges and analytical methods. [Article]. Journal of Business Research, 70, 263–286. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2016.08.001

25. Wamba, S. F., Gunasekaran, A., Akter, S., Ren, S. J. F., Dubey, R., & Childe, S. J. (2017). Big data analytics and firm performance: Effects of dynamic capabilities. [Article]. Journal of Business Research, 70, 356–365. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2016.08.009.

Thomas Fischer (American Society for Cybernetics)

Cybernetic reentry: towards a reflexive pedagogy for cybernetics

Abstract.As a way of conceptualizing and of pursuing epistemological practices, such as learning, designing and researching, cybernetics should enjoy a front row position within academic settings today. However, being aligned orthogonally to – and occasionally challenging – the utilitarianism, revenue models, reward-orientation, and control structures of many academic and research organizations, cybernetics as an academic discipline is in serious crisis. In many parts of the world, it no longer enjoys the levels of funding support, student numbers, academic workforce and opportunities to offer study programs it enjoyed a few decades ago. While many cybernetic ideas and theories have been absorbed by other fields, where they are pursued in specialist engineering approaches, the study of cybernetics as a generalist philosophy has all but disappeared from formal curricula in many parts of the world. Furthermore, in many parts of the word the more generalist subject of cybernetics and its more specialist sister subject of computing have drifted apart, resulting in a disciplinary as well as philosophical fragmentation of the field.

Keywords: Cybernetics, reflexive pedagogy, second-order cybernetic concepts

In some ways, cybernetics is back where it was shortly after World War II, having to rely on its appeal to bright and enthusiastic minds to approach and pursue the subject, to build new communities, and to develop the future of cybernetics practically from scratch. Given the success of cybernetics in the middle of the last century, it is prudent to take a look back, and to examine how early cybernetic thinkers may have connected with control and communication early in their lives.

It may be no coincidence that cybernetics owes its greatest advances to a generation, which, during its childhood years, commonly played with toy steam engines. This toy may very well have played a key role in acquainting this generation early on with principles of control and communication, of measurement, signaling and adaptation via feedback, to instill an interest in self-regulating systems. Being mass manufactured, the toy steam engine was itself a product of the industrial paradigm initiated by its full-scale predecessor, and as a miniaturized reincarnation, it helped a new generation to pave the path from the industrial era to the information era.

In the information age, however, technical principles of communication and control manifest themselves far beyond the thresholds of human perception in miniscule, electrical and optical signals, and have thus escaped from the realm of playful childhood experience. In contrast to the steam engine and the immediate comprehensibility of the functional principles underlying its operation, more recent cybernetic concepts are less accessible to early learning and study. This begs the question: What learning resources and playthings can cybernetics offer to young people in this day and age to learn its key principles, and to possibly help develop cybernetics further in the future?

In the past decade, there have been proposals and initiatives the within the American Society for Cybernetics (ASC) to develop an introductory course to cybernetics, referred to as "Cybernetics 101". For the most part, these initiatives are currently dormant. One important reason for this appears to be a dilemma between the ambition to create a general, one-fits-all curriculum on the one hand, and the large degree to which the promotion of cybernetics depended on particular individuals in the past.

This is a proposal for a presentation of an initiative that aims to develop a suitable and contemporary pedagogy for cybernetics and related learning materials for both individual as well as for organized learning. It is at this time a personal initiative, but this may change in the future. Analogously to Margaret Mead‘s (1968) call to the American Society for Cybernetics to apply cybernetics to itself ("cybernetics of cybernetics"), it aims to utilize cybernetic resources and accomplishments of the past in the pedagogy of cybernetics to perpetuate the discipline into the future in times of dwindling institutional support. It takes a hands-on, constructivist learning approach with a focus on applied computer-programming based exercises using low-cost hardware and free software.

Its primary goal is to introduce key first- and second-order cybernetic concepts developed since World War II in a way that is accessible for speculative interaction and digital experimentation, somewhat in the way the toy steam engine gave access to experimentation with self-regulation in mechanical systems. It is hope that this will help re-align the developments of cybernetics (as a philosophical field) and computing (as an engineering field) in some places.

The computing field, itself a spawn of cybernetics in some ways, recently experienced a proliferation of study and play resources for "makers" and young people to familiarize themselves with digital technology, programming and networking. Of these, the single-board low-cost computer Raspberry Pi, its open-source operating system Raspbian (a Debian-derived Linux) and the programming language Python 3 were chosen at the technical basis for this project.

The course is designed to enable both individual self-study as well as formal classes, and it fit the scope of a one-semester introductory undergraduate module. As a electronically enhanced textbook, it offers a coherent overarching narrative that is illustrated and substantiated by various demonstrations, anecdotes, short audio and video clips of cybernetic sources, and, first and foremost, hands-on exercises. Aiming to inspire an appreciation for the concerns and characteristics of cybernetics, the course design currently focuses on assumptions that set cybernetics apart form other fields in the systems research family, as well as from conventional natural science: Observer-dependence, non-determinability, circular causality, and self-organization.

The majority of the hands-on exercises takes the format of applied coding assignments. "Technical" approaches have more conventionally been associated with first-order cybernetics and utilitarian control systems. In this case, however, computer technology is taken as an output of past cybernetics to illustrate and inspire cybernetics and cyberneticians of the future. The hands-on exercises include: A programmable Turing Machine, a simple Wiener anti-aircraft predictor, a thermostat data logger, a Shannon mind reading machine, demonstrations of subjective participation in observation, various eigenwert and eigenbehaviour demonstrations based on recursive functions, a simulation of the Ebbinghaus "forgetting curve", and an implementation of Varela‘s autopoiesis cellular automata system.

The course has recently been delivered at the Institute of Media Science at Humboldt University in Berlin, and further deliveries are planned. The textbook and exercises are currently developed in German language and are scheduled to be published in a text book format soon. An extended version in English language is planned for the intermediate future. The proposed presentation will introduce the initiative and its underlying motivation, and offer a guided tour through key software exercises with short discussions of related cybernetic principles and ideas.

References1. Mead, Margaret 1968. Cybernetics of cybernetics. In: Foerster H. von et al. (eds.) Purposive Systems. Proceedings of the First Annual Symposium of the American Society for Cybernetics. New York, NY: Spartan Books. 1-11.

Tatyana Medvedeva (Siberian State University of Transport, Novosibirsk)

View of V. E. Lepskiy’s and S. A. Umpleby’s theories of cybernetics through the prism of intellectual traditions

Abstract.Understanding the differences between scientific approaches to cybernetics is difficult because of the very different histories and intellectual traditions in Russia and the US. This paper, first, describes the peculiarities of the Russian style of scientific thinking in comparison with the American approach. Second, it compares Vladimir E. Lepskiy‘s and Stuart A. Umpleby‘s theories of cybernetics looking at them through the prism of Russian and American intellectual traditions.

Keywords: intellectual traditions; first-order cybernetics; second-order cybernetics; third-order cybernetics

The Russian intellectual traditionCharacterizing the Russian intellectual tradition in comparison with the American intellectual tradition requires describing several points. Therearefundamentaldifferences. Among the most important differences, from our point of view, are the following:

1. Different interpretation of some fundamental concepts, for example, the definition of "development". "Development" has been interpreted in the West mostlyin terms of technology and science (a technocratic view of the term). Technologicalprogressisamainstreamidea. ButRussian civilization interprets "development" as transfiguration, self-perfection, vanquishing sinin people (a spiritual view of the problem).[Platonov, 2010]

2. The scientific implications of such a different understanding of fundamental ideas can be illustrated by the American and Russian development of the idea of I. P. Pavlov on the "conditioned reflex".Pavlov discovered a conditioned reflex while experimenting with animals as a physiologist. Later he learned that American psychologists were experimenting in the same way. He wrote about the difference between his work and the American work by noting that the practical American mind found that it is more important to know the external behavior of a man, than to guess about his internal state. The American science of behavior teaches us to act in the right (instrumentally successful) way. Russianpsychologyteachesusto make right (ethical) decisions.

3. Many Russian scientists often used different foundation for their process of thinking, they strove to build a better world, to include ethics and spirituality in scientific theories (N. A. Berdyaev, N. G. Chernyshevsky, and others). The first systematic critiques of classical rationalism as a scientific position were formulated in Russia. (Although rationalism led us to the gate of truth, it is fated not to open the gate. I. Odoevsky).

Russians feel a need to understand the world as a whole. Therefore, they emphasize different patterns in the world, society and nature than are emphasized in the Western intellectual tradition. For example, academician N. N. Moiseev stressesed that the formation of a global collective consciousness lays the foundation for the development of an information society. He wrote: "The notion of collective consciousness is a fundamental notion of civilization… Civilization itself could not emerge without development of a collective consciousness. This phenomenon emerges as an effect of the necessity and possibility of information exchange among individual consciousnesses, evolution of collective memory and organisation of collective efforts in decision making." [Moiseev, 2000] Western academics are more likely to speak about "shared beliefs and values" rather than a "collective consciousness."

4. Russians prefer a systematic approach and have a tendency to create general theories. Examples are such well-known names as N. I. Lobachevsky, D. I. Mendeleev, A. A. Bogdanov, N. F. Fedorov, V. I. Vernadsky, K. E. Tsiolkovsky and others.

Hence, Russian scientific thinking can be characterized by thesystems approach, a striving to create general theories, including a moral component in them,and acceptance of irrationality.

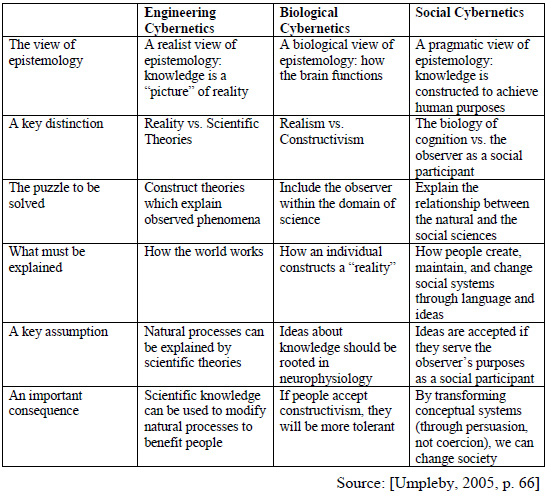

Comparison of V. E. Lepskiy’s and S. A. Umpleby’s theories of cyberneticsUnderstanding the differences in intellectual traditions leads us to a deeper understanding of the theories of cybernetics of V. Lepsky and S. Umpleby as representatives of these scientific traditions.Table 1 presents a description of the development of cybernetics, made by S. Umpleby.

Table 1. Three versions of cybernetics

In spite of the fact that the table is called "Three versions of cybernetics," Western scholars only single out cybernetics of the first and second orders. Cybernetics of the second order includes a biological and social version. It arose from "experimental epistemology." The goal was to understand the processes of cognition on the basis of neurophysiological experiments, as a result of which cyberneticians came to the conclusion that the observer can not be excluded from science.

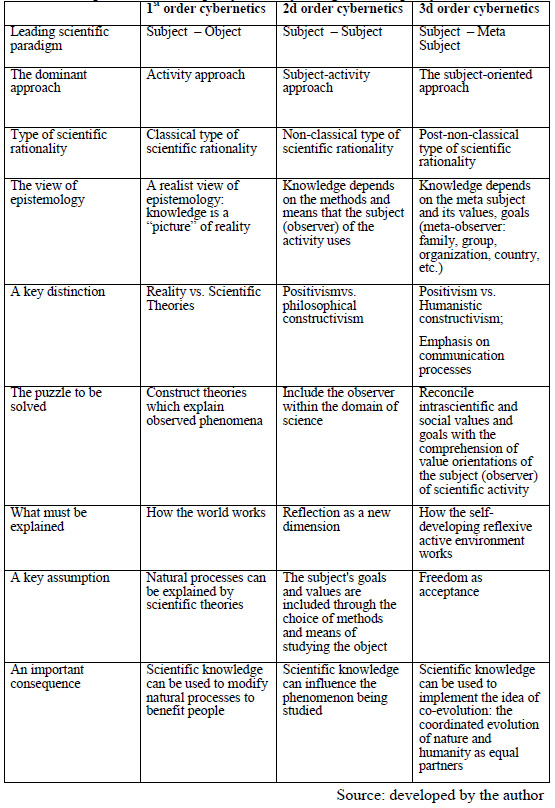

Table 2. Description of V. E. Lepskiy's theory using S. A. Umpleby’s criteria

The Russian interpretation of second-order cybernetics is different from the Western concept of it. Table 2 presents a description of Lepskiy's theory using Umpleby's criteria.

The development of the conception of third-order cybernetics is based on Russian ideas: the activity approach, the typology of scientific rationality, the inclusion of the moral component, etc., are not well known in the West, which leads to some misunderstanding of concepts.

ConclusionsBriefly, the main differences between the theories of V. E. Lepskiy and S. A. Umpleby, from our point of view, arethe following:

– the American vision of second order cybernetics includes the biological and social versions; the development of cybernetics takes place within the framework of the paradigms of classical and non-classical rationality;

– the Russian vision of the second order cybernetics excludes from consideration the biological version, in fact, reducing second order cybernetics to the cybernetics of the individual subject (observer) and, indirectly, its values (through the choice of methods and means of studying the object), in contrast to the third-order cybernetics concept with its focus on the social (meta subject);

– Western scholars do not consider third-order cybernetics to be necessary, since the inclusion of an observer (subject) in the field of science, from their point of view, solves the problem of including social values and goals into consideration [Medvedeva, Umpleby, 2003];

– it seems that V. Lepskiy's theory of the third-order of cybernetics develops in the direction of typically Russian ideas: "noosphere", "collective consciousness", "co-evolution", etc., i.e. it is not just social cybernetics, but cybernetics of environments, and probably one can say cybernetics of nature.

The presented differences demonstrate the great potential forideas from Russian and Western scientists to enrich the further development of cybernetics and science in East and West.

References1. Platonov O. A. Russian civilization. History and ideology of Russian people. – Moscow: Algorithm, 2010. – 944 p.

2. Lepskiy V. E. Evolution of cybernetics: philosophical and methodological analysis. -Kybernetes, 2017.

3. Umpleby S. A. A History of the Cybernetics Movement in the United States // Journal of the Washington Academy of Sciences, Vol. 91, No. 2, Summer 2005, pp. 54–66.

4. Moiseev N. N. The fate of civilization. The path of the mind. – M.: Languages of Russian Cultures, 2000. – 224 p.

5. Medvedeva T. A., Umpleby S. A. Adding a dimension to the philosophy of science with an illustration from economics. – Presented at the Socio-Cybernetics conference, Corfu, Greece, June 29 to July 5, 2003.

В. А. Лефеер(США)

Рефлексия и музыка

На первый взгляд между рефлексией и музыкой нет связи. Рефлексия – это цепочка образов в нашем внутреннем мире: образ себя, образ себя у образа себя и т. д. Музыка – это набор звуков, которые вызывают у нас эмоции. Отношение частот двух звуков, генерируемых синхронно или последовательно, называется музыкальным интервалом. Уже в древности было обнаружено, что только некоторые интервалы приятны для человеческого уха. Например, 4/7 звучит хорошо, а 5/7 – плохо. Приятно звучащие интервалы были названы гармоническими. Их всего восемнадцать, они известны музыкантам многие столетия. Причины, почему одни интервалы приятны, а другие – нет, до сих пор недостаточно ясны. Термодинамическая модель рефлексии может помочь нам понять загадку музыкальных интервалов.

Сущность модели такова. Рефлексии соответствует цепочка абстрактных тепловых машин. Работы, выполняемые машинами, интерпретируются как эмоции. Первая машина в этой цепочке это субъект, вторая – его образ себя, третья – образ себя, который есть у образа себя и т. д. Модель основывается на двух первых законах термодинамики: законе сохранения энергии и законе неубывания энтропии. С помощью этой модели строятся диафантовы уравнения, и показывается, что корни этих уравнений совпадают с множеством гармонических интервалов. Особую роль играют квинта (2/3) и кварта (3/4). Именно от связи между ними зависит восприятие звучания всех других интервалов.

Таким образом, уподобляя работу нейронных сетей мозга работе цепочки тепловых машин, термодинамическая модель рефлексии объясняет привлекательность музыкальных интервалов.

Во втором издании моей книги "Что такое одушевленность?" подробно описывается термодинамическая модель и показывается связь рефлексии и музыки.

В. А. Бажанов, А. Г. Краева (Ульяновский государственный университет)

Нейропсихологические предпосылки процессов саморефлексии субъекта познания в контексте трансдисциплинарного подхода

Аннотация. Предлагается гипотеза, согласно которой рефлексивные процессы были запущены на нейробиологическом уровне, что предопределило жизнестойкость человека и его способность к гибкой адаптации, предполагающие функционирование механизмов самодостраивания.

Ключевые слова: субъект познания, саморефлексия, самодостраивание, эффект Болдуина, когнитивный модуль, трансдисциплинарный подход, общество знания, рефлексивно-активные среды.

V. A. Bazhanov, A. G. Kraeva (Ulyanovsk State University)NEUROPSYCHLOGICAL PREREQUISITES OF COGNITION SUBJECT REFLEXIVITY IN THE CONTEXT OF A TRANSDISCIPLINARY APPROACH

Abstract. A hypothesis put forward, according to which human reflexive processes are determined on the neurobiological level. This idea enables to explain the features of vitality and capacity for flexible adaptation involving the functioning mechanisms of self-reflexion.

Keywords: subject of cognition, self-reflexion, self-construction, Baldwin effect, cognitive module, transdiciplinary approach, the knowledge society, technoscience.

1. Анализ междисциплинарных, полидисциплинарных и трансдисциплинарных процессов в современной науке и культуре объективно показывает, что именно трансдисциплинарность во многом определяет новейшие тенденции развития современной науки и культуры. Она является основой для конвергенции фундаментальной науки и технологий, исследований когнитивных феноменов в целом. Это, в свою очередь, обусловливает необходимость реализации одной из генеральных программ современной науки и её составляющих в виде выработки методологической платформы формирования общества знания и, в частности, технонауки. Здесь происходит своего рода синтез научного и технического знания, который может быть осмыслен в аспекте выработки модели общенаучной рефлексии, выступающей в качестве катализатора интертеоретических обменных процессов, в явном виде учитывающих когнитивные процессы.

2. Специфика сложившейся сегодня интеллектуальной ситуации в российском обществе такова, что знания о рефлексивных процессах и четко оформленная рефлексивно-аналитическая позиция необходима в силу определяющих тенденций в социальном организме: всё увеличивающегося разрыва между наукой (интеллектуальной элитой в целом) и властными структурами, заметного снижения непосредственного участия социума в принятии решений, связанных со стратегическим управлением инновационными процессами, и, главное, отсутствия убежденности в его необходимости, понимания его смысла. Современное российское общество характеризуется «бессубъектностью» [Лепский В.Е., 2016, с. 18], что во многом вызвано резким возрастанием сложности процессов личностной идентичности субъектов российского общества.