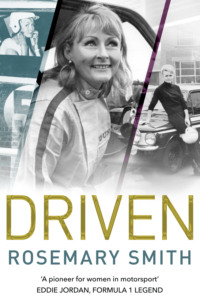

Driven: A pioneer for women in motorsport – an autobiography

Copyright

HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

First published by HarperCollinsPublishers 2018

FIRST EDITION

© Rosemary Smith 2018

Cover layout design by Claire Ward © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2018

Cover photographs courtesy of the author

All other images courtesy of the author unless otherwise indicated.

While every effort has been made to trace the owners of copyright material reproduced herein and secure permissions, the publishers would like to apologise for any omissions and will be pleased to incorporate missing acknowledgements in any future edition of this book.

Rosemary Smith asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record of this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

Find out about HarperCollins and the environment at

www.harpercollins.co.uk/green

Source ISBN: 9780008301859

Ebook Edition © October 2018 ISBN: 9780008301873

Version: 2018-09-13

Dedication

Dedicated to Patricia (Pat) Doyle,

my lifelong friend

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

FOREWORD BY EDDIE JORDAN

INTRODUCTION

CHAPTER 1: THE START

CHAPTER 2: SPECIAL STAGES

CHAPTER 3: ‘YOU DRIVE,’ SHE SAID

CHAPTER 4: AND WE’RE OFF!

CHAPTER 5: REVVING UP WITH ROOTES

CHAPTER 6: THE AMERICAS

CHAPTER 7: AVOIDABLE ACCIDENTS

CHAPTER 8: MOVING ON

CHAPTER 9: DOWN UNDER

CHAPTER 10: SOUTH OF THE BORDER

CHAPTER 11: MEN, MARRIAGE AND MORTGAGES

CHAPTER 12: RAINY KENYA

CHAPTER 13: RACING AROUND

CHAPTER 14: FROM BAD TO WORSE

CHAPTER 15: ROCK BOTTOM

CHAPTER 16: LET’S FACE IT

CHAPTER 17: IN BUSINESS

CHAPTER 18: SEEKING SOLUTIONS

CHAPTER 19: RECOLLECTIONS AND REGRETS

CHAPTER 20: DÉJÀ VU

CHAPTER 21: PASSION FOR LIFE

PICTURE SECTION

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

LIST OF SEARCHABLE TERMS

About the Publisher

(Independent Newspapers Ltd)

Foreword

by Eddie Jordan

I hear people these days talking non-stop about passion and commitment, and that’s great, because without them there won’t be success. But these two elements come after the primary vital ingredient: inspiration.

Rosemary Smith inspired a generation of young Irish drivers, myself included, to pursue our dreams of an international career. As a young lad going to Synge Street School in Dublin, I was mad about cars – inspired initially by my cousin Noel Smith, who was a fine rally driver and got his hands on a Porsche 911 from time to time. But up in the stratosphere there was a supercool Irish icon who inspired the following generation of Irish drivers that we could achieve success on the international stage – and that icon was Rosemary Smith.

Like most young car nuts of that era, I bought Autosport when I could, and I remember Rosemary getting the front cover for her heroic outright win in the Tulip Rally in 1965. It was the equivalent of a WRC event today. The Swinging Sixties was in full flow in London and Paddy Hopkirk’s Monte Carlo Rally wins brought the Mini (the car, not the skirt!) and motorsport on to the front pages and into the social columns. Motorsport was uber-cool and Rosemary was the queen of it. She was an Irish superstar, a Dusty Springfield lookalike who was incredibly talented behind the wheel.

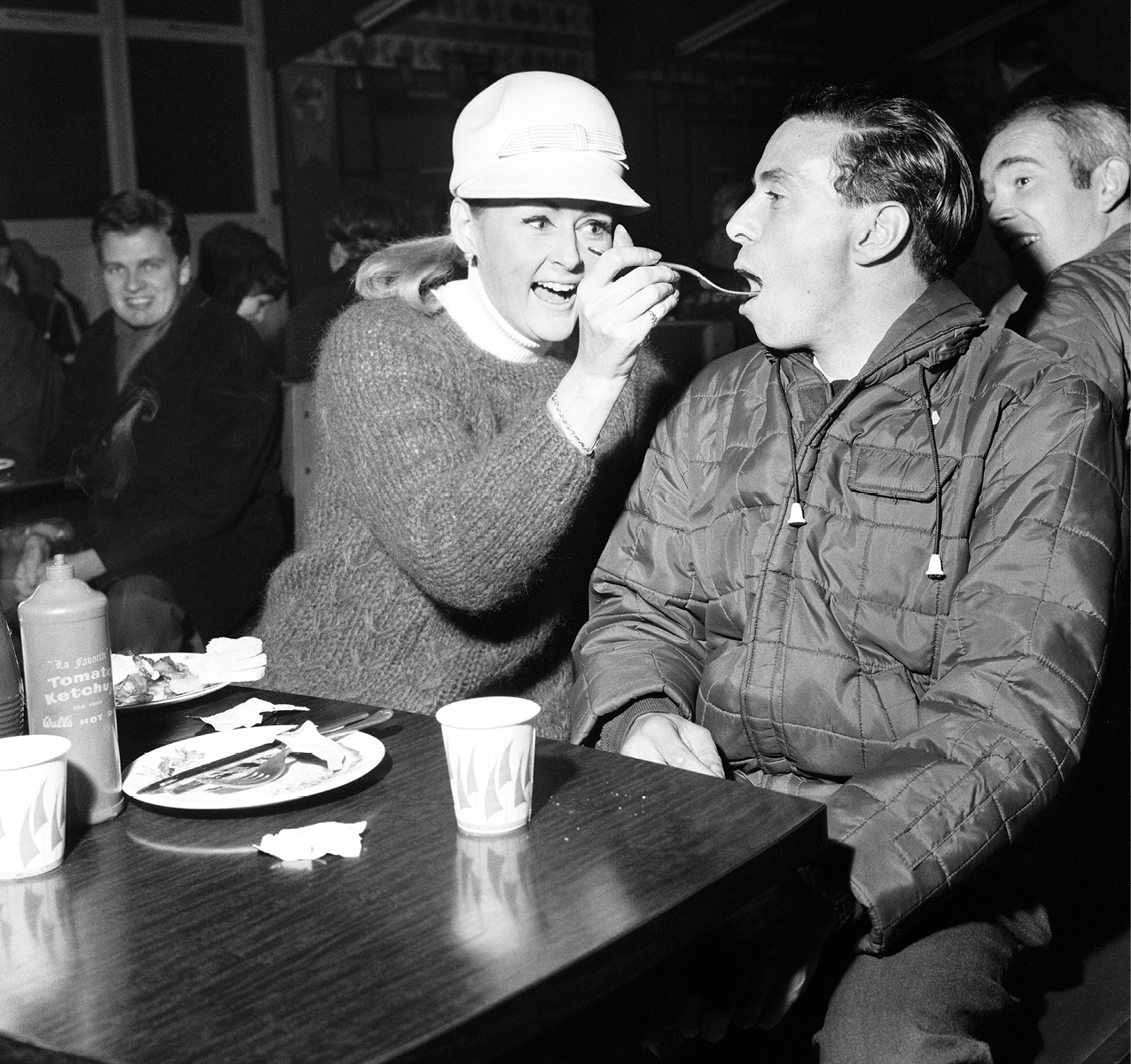

Breakfast with Jim Clark on the RAC Rally in the 1960s (Mirrorpix)

In 1966 I did my Leaving Cert (A-levels) and Rosemary was entered into the RAC Rally, reports of which we followed in detail when we should have been studying. There were 150 entries headed by Jim Clark and Graham Hill – two racing world champions. The real Stig (Blomqvist) and Roger Clarke and dozens of other rally aces were joined by Rosemary in her tiny Hillman Imp. She has an incredible knack of being able to drive error-free and managed to be one of only 50 finishers, ending in a magnificent 14th place.

Rosemary was incredibly glamorous and made rallying and racing the sport we longed to be part of. She was a rare Irish driver on the world stage and it is great that in motorsport she is still treated like royalty – in fact, better than royalty – and she deserves it.

We first met around 1975 when I was starting to race in England, with Aintree being the closest UK circuit, and she was campaigning a Ford Escort. She was a fine circuit racer who could hold her own against the best. The Renault F1 team told me in 2017 that they were going to give her a run at Paul Ricard and I was delighted.

Rosemary is a pioneer for women in motorsport and remains a great ambassador for her sport, and especially women’s place in it. Hers is a remarkable story of a lifetime of success at the very highest level in one of the most male-dominated sports on the planet. It is a story every aspiring driver can draw inspiration from.

Introduction

As I sat behind the wheel of Renault’s 800bhp Formula 1 car, my hands were sweaty, my pulse was racing and my heart was banging away in my chest. What had I let myself in for? A week before, I had been happily drinking tea and watching Flog It on the telly and now I was surrounded by film cameras and mechanics all yelling instructions at me. As I wedged my body into the car and the mechanics wheeled me out of the garage, I was shaking. I was nervous, terrified, but nothing was going to stop me. I hadn’t felt like this since I attempted to break the Irish National Land Speed Record in 1978. As I began to drive, the noise was deafening, but all I could do was keep going as the air whistled past me. It was then that the adrenaline kicked in and I was away, without a thought for my safety or survival. The sheer excitement of it all overtook me as the engine roared and my speed increased. I had fire in my belly and I just went with it. Fright and exhilaration all at the same time, a sensation I will never forget!

It was a truly amazing experience and the only reason I became involved was because two charming men, Paddy McGee and James Boyer of Renault, suggested it. They wanted to make a documentary of the old girl driving a Formula 1 car around the Circuit Paul Ricard in France and it didn’t take much to persuade me: I love a challenge. I was well known in motorsports circles in my day, having achieved notoriety for competing against, and sometimes beating, many of the male drivers, but I was never really famous until I went to Marseille in June 2017 to drive that Formula 1 racing car. After that, I received more publicity than I ever had before in my entire life. Of course, when I was driving in rallies and racing all over Europe, there was no social media to promote events and certainly no Google or YouTube. The documentary made of that Formula 1 drive has thousands of hits on YouTube and they keep telling me I have gone viral, but that just sounds like a bad dose of the flu to me!

When I was asked to go to Silverstone prior to the British Grand Prix to celebrate my Formula 1 drive, I was treated like a celebrity and that’s a nice feeling when you are coming up to your 80th birthday. I’ve had six stents inserted, a broken collarbone, a cracked kneecap and a sprained ankle (and none of them in a car) and I survived. Eighty isn’t old any longer and I see no reason to stop doing the things I love. A lot of my contemporaries are still going strong: Paddy Hopkirk, Jackie Stewart, Rauno Aaltonen – I see them all at functions and parties.

I am enjoying life to the full; running the driving school, giving private lessons and generally keeping busy. Recently, I gave a talk to a large group of people at a seminar in the International Financial Services Centre in Dublin. ‘Are you sure?’ I asked the woman who telephoned to ask me to do the talk, because I knew the people attending would all be highly educated with senior positions in their organisations. I only know how to drive cars and win rallies, but apparently that is enough. I rarely turn anything down, but I did a week ago when I was asked to take part in an event testing a self-driving car. ‘Autonomous,’ they call them. I was supposed to sit in the car with the windows blacked out and a little laptop on my knee to steer. That I declined to do!

People often ask, When are you going to retire? and I just laugh at them. Do they really believe I could sit watching television and eating marshmallows with my feet up for the rest of my life? I am glad to say that there is always something to be done. I have a huge calendar on the wall, on which I write down all my appointments, and as I sit looking at it today, my life looks very full. Last week, I had a telephone call from a man asking me to drive his car from London to Spain next year in a classic rally. I said I would, thanks very much, but these days I always include the proviso: If I’m still alive.

I contemplate death from time to time but I sorted out my funeral arrangements long ago. When my mother died, I had a headstone made for the family grave in Deansgrange and it set me thinking about how I would like to go. In 2003 I saw Adam Faith’s funeral on the television and he was the first person I had ever seen buried in a wickerwork casket and I fell in love with it. I have observed so many beautiful oak coffins go through those curtains at the crematorium and I think it’s a disgrace and a terrible waste of good timber! I am sure they unscrew the brass handles to be recycled before they reach the furnace, but even so …

I talked to my friend, Pat Doyle, who told me about a very good funeral parlour in Bray, County Wicklow, and I asked her to accompany me so that we could order the casket. It was a lovely place, and when we entered, a very suave gentleman approached us, looking suitably sombre. ‘I want to order a coffin, please,’ I said. ‘It has to be a wickerwork casket and must be sprayed pink.’ The man replied that this was most unusual but it could be done and then he wanted to know who had passed away. ‘It’s for me,’ I told him. ‘Could you let me know when you want it?’ he asked. ‘I’m not sure,’ I replied, ‘but my friend Pat here will let you know.’

We went out of that funeral parlour laughing our heads off and drove straight to the solicitors to make my will. I gave my solicitor details of friends and family to whom I would bequeath whatever I had left and he duly took notes. Then I told him about my visit to the funeral director and all about the pink wickerwork casket I had ordered. When I am cremated, I want the church softly lit as I look better in low lighting and nobody is to wear black, nobody, I told him. As my casket is wheeled up, I want the music ‘Blaze Away’ by Josef Locke, singing about making a bonfire of his troubles and watching them blaze away. Then, as I am going through the curtains, Andrea Bocelli and Sarah Brightman will be singing ‘Time to Say Goodbye’, and if you could arrange for an enormous cardboard hand to be waving at everyone that would be great. The poor solicitor is still looking at me!

The will and the funeral arrangements are all sorted but I’m not ready to say goodbye just yet, and before I go I am determined to do what so many people have suggested: tell my story. I have driven cars in rallies all over the world – Africa, Canada, Europe, Australia, New Zealand, Tasmania, you name it, I’ve been there – but when I started off on my career, 60 years ago, I had no idea that anybody would have the slightest interest in my story and so I didn’t make notes and I have never kept a diary – when things are over, they are over as far as I’m concerned. So this is what I’m up against, but I will do my best to write about my life as honestly as my memory allows.

September 2018

CHAPTER 1

The start

Despite what some people think, I wasn’t born with a silver spoon in my mouth. For some reason, people always have the impression that I come from a very wealthy family. The truth is, we were always on some sort of economy drive, although my mother did her best to ignore that. My dad, John Metcalf Smith, had a small garage in Rathmines and in the early days, when there were very few cars on the roads, there was not a great deal of business. But he was a good, kind man and people took to him and the clients he had were loyal. My dad was a Methodist and he had what I call the Protestant ethic: hard-working, reliable and straight as a die. My mother, Jane, was a Catholic, and as well as the religious divide, there was little else they had in common. As it was a mixed marriage, the ceremony took place on the side altar of the church in Dunboyne, County Meath. In the late 1920s, if a Protestant married a Catholic, a solemn promise was made whereby the children of the marriage would be brought up as Catholics. My father was scrupulous in this regard and every Sunday he dropped us all off for Mass and then went on alone to the Rathgar Methodist Church on Brighton Road.

My parents had three children in quick succession and I was the youngest of the family; Pamela was the eldest and Roger was the middle child. Pamela was beautiful, small and dark with lovely eyes. Dad’s mother and father were not happy with him marrying a Catholic. Once Pamela arrived, all that changed, because she was the most adorable baby. At school, she passed every exam with flying colours but she had no interest in clothes or fashion, much to my mother’s disappointment. When they went out to buy a new coat or dress, Pamela would have a book in her hand, and would barely look up when my mother asked her opinion on the item in question. Instead she just nodded her head and turned over the page. She always seemed to me to be totally self-contained; she did her own thing from a very early age. After leaving school, she went to London to study at a Montessori Teacher Training College. Pamela just wanted to get away, and who could blame her? Our home was not a peaceful one. My mother was constantly nagging and having tantrums and Dad seemed unable or reluctant to stand up to her; he adored her.

Pamela, who never smoked or drank, died of cancer when she was 64. She had five children and lived near Seattle, in the USA, in a house overlooking the Puget Sound. My mother favoured my brother, Roger. Roger was lovely and, if he were around today, he and I would be great friends. Poor Roger died tragically of a heart attack at 42 years of age, when his wife, Jackie, was pregnant with their second child. When Roger left school, he helped Dad run the garage. But the way Roger wanted to run the business was totally different from my father. Someone would come in for work to be done and Roger would give an estimate and Dad would say, ‘No, no, he’s a good customer and maybe he mightn’t have the money.’ ‘Of course he’s a good customer if we don’t charge him,’ Roger replied. I might be a millionaire now if I hadn’t inherited my father’s lack of business acumen.

In the early days, one of my father’s customers was Jeff Smurfit, who owned a small business and rented a shed around the corner from Dad’s garage in Rathmines. Sometimes his truck would break down in the middle of the night and my father thought nothing of going out to help him, whatever the time of day, much to my mother’s annoyance. Mr Smurfit was always late paying his bills, which annoyed her even more. At the end of one month, the bill was particularly high and Jeff Smurfit made my father an offer: ‘Instead of paying the bill, I’ll give you half the business,’ he said. The business was a small box company, which wasn’t doing too well, and my mother didn’t like this idea at all and told Dad to refuse. Sometimes you miss the boat; Dad certainly did on that occasion – Smurfit’s is now a multibillion-dollar business. If only my dad had taken the chance with Mr Smurfit, if only he had let Roger run the business, if only … If ‘ifs’ and ‘ands’ were pots and pans, there’d be no work for tinkers’ hands … you know that silly saying. My dad’s work ethic was to do an honest day’s labour without taking advantage of his customers. He lacked real business flair, however, and his heart often ruled his head, except when my mother got in the way.

Roger couldn’t work with my father – their ideas on how to run a business were totally different, but they both loved cars and competed in a few races without much success, I’m sorry to say. They didn’t have decent cars and despite the fact that he was a good driver, probably better than me, Roger never reached his potential. After practice he would be delighted to find himself in pole position and then in the race, after two or three laps, the car would blow up.

Roger took off to England to work for a Ford dealership and I never saw much of him after that. In their spare time, he and a friend of his drove around the countryside of Yorkshire, calling into farmhouses and cottages looking for clocks that didn’t work and offering to buy them for little or nothing. ‘Oh here, take it away, it hasn’t worked for years,’ people would say. They accumulated an assortment of clocks, which they tried to repair, not always successfully, and then sold them on at markets and to antique shops. Roger was a very good salesman and this was a nice little sideline for a while.

My wonderful dad taught Roger, Pamela and me to swim and drive when we were very young – ‘In case of emergencies,’ he said. We learnt to drive in a big old-fashioned Vauxhall and I was only 11 when I first got behind the wheel. I loved it from the off; I was so small that I had to sit on cushions to see over the steering wheel. Dad had bought a field in Old Bawn, Tallaght (one of his better ideas), and we would drive round and round on the wet grass. Little did I know at the time, but this experience was to come in useful years later when I drove in the Monte Carlo rallies over those icy roads in Europe.

My dad was right about emergencies, because learning to drive at such a young age came in very handy one day. I must have been about 13 when it happened. My mother and I were alone in the kitchen in our house in Rathfarnham. She had been washing dishes in the sink and with wet hands she tried to pull the plug of the electric fire out of the socket on the wall. In those days plugs weren’t earthed, and she screamed as she dropped to the stone floor, unconscious, still clutching the plug. I rushed to her side, pulled the plug from her hand and quickly decided I had to get her to a doctor. We had a telephone but for some reason it didn’t occur to me to ring for my father or an ambulance – I didn’t stop to think, all I was concerned with was getting help as soon as I could. I dragged my mother outside and somehow got her into the old Vauxhall parked in the driveway. The driveway was very narrow, barely the width of the car, and I bumped along, hitting the walls on either side. Somehow I managed to get out of the driveway, on to the steep hill and turn right.

I was in first gear as we chugged down to Dr Donald, who lived on our road in the first house over the bridge. He was just on his way out when we arrived and you can imagine his amazement when he saw me driving the car with my unconscious mother in the back. He gave her CPR and called an ambulance and gradually she came back to life. My mother wasn’t dead and the doctor congratulated me and assured me she was going to be all right. It was then I started shaking as the enormity of what I had just done overcame me. I left the car there and ran home.

We went most years to Bettystown, a small village on the coast in County Meath, for our holidays. It was lovely there – beautiful beaches and long, lazy days of doing nothing. My father loved golf and he played in all weathers. Thunderstorms didn’t bother him; he just didn’t seem to care as he had a most peculiar affinity with the elements. Mother said he could have been killed with a steel club in his hand and the lightning flashing. I was preoccupied with other things and got my first kiss on the beach in Bettystown from a 14-year-old boy from Glasnevin and I thought I was in love.

On the drive to and from Bettystown, I often felt sick sitting in the back of the car. Our old car would wobble along and then, as I watched the cars flashing by out of the side window, I would get dizzy and shout to my father to stop as I was going to be sick. I only ever felt ill when someone else was driving; when I was behind the wheel, I was perfectly fine. Driving was something that I could do well and I badly needed something to boost my confidence. I was dreadfully shy, maybe because I grew so tall at a very young age, and I used to walk around with my head and shoulders down, trying to make myself smaller, my arms dangling like a gorilla.

I remember my first dance. I was sitting on a chair at the side of the hall, as was the custom: boys on one side, girls on the other. A good-looking boy crossed the floor, his dark hair stiff with Brylcreem, and asked me to dance. I was thrilled, but when I stood up I was towering over him; he made some hasty excuse and ran off. As I surveyed the boys in the hall that night, it seemed to me that they were all training to be jockeys.

It took me years to get over my shyness. It was so bad at one stage, whenever we won something in a rally, I would send my co-driver up first to collect the trophy, but once I got into a car I felt insulated and confident. I was always happiest behind the wheel. Maybe in the beginning the car was like a home for me, the only thing I had complete control over and where I felt secure. Growing up, there was little sense of security and maybe this was because our family lived in so many different locations. My mother was a nomad and never wanted to be in one residence for long. We lived in so many places: Bray, where I was born, then Dundrum, Terenure, Rathfarnham, Blackrock and Sandymount before finally settling down in Dunboyne, County Meath. I grew up falling over paint cans and ladders. When I got married I would stay in the same house all my life, I vowed, but the best-laid plans of mice and men often go awry, as the saying goes.