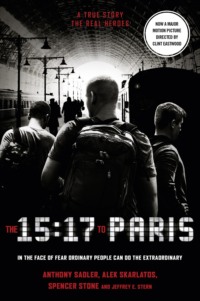

The 15:17 to Paris: The True Story of a Terrorist, a Train and Three American Heroes

AUG 13, 11:49 AM

Joyce Eskel:

Spence how is your ankle? What happened?

AUG 18, 6:50 PM

Joyce Eskel:

Hey need to post pictures!!!

1.

JOYCE ESKEL CLOSED THE COMPUTER with an uneasy feeling.

She didn’t love the idea of Paris. She’d followed the story of the terrorists attacking the magazine there, Charlie Hebdo, a few months back. She’d been reading about Islamic extremists since 9/11, and she knew France had open borders. Paris was a big city of course (she’d been there before, but that was many years ago now) and the odds that the boys would be at any kind of risk were low. She knew that.

Still, she felt something.

Plus Anthony was there, and whenever her son got together with Anthony, things just happened. Two weeks into their trip, she couldn’t quite believe they’d managed to avoid major catastrophe.

Although they’d avoided major catastrophe only barely. She knew about the two drinking just a little too much, so that Spencer stumbled over a cobblestone and nearly broke his ankle, on the very first night of their trip. Spencer told her, when he connected to the Internet, that he might need to call it off and go back to base. Call off the whole trip, done on the first day. Could you even get an X-ray there? Would his insurance cover it?

It was uncanny, how they brought the mischief out in one another. She couldn’t figure out their relationship, two mostly laid-back kids who didn’t seem to have much in common, but when they were together … She remembered once when they were in eighth grade how they’d redecorated the neighbor’s house with a dozen rolls of toilet paper, then took turns ringing the doorbell and diving for cover in the hedges. When together, the two just seemed to love trouble.

So she sat down after closing the computer, and thought about the feeling. Twenty years ago she might have dismissed it; now she knew what it was. The still, small voice. She called it “intuition” to those who wouldn’t understand; to those who would, she called it what she knew it was: God. Preparing her for the events that would follow, just as he’d done countless times before, once she learned to listen, warning her when her children were in danger. What mattered now was what to do with it, and so she decided to do what she always did in situations like this: she prayed. Joyce Eskel closed her eyes, bowed her head, and prayed that things would turn out okay for the boys in France.

BY THEN, JOYCE HAD LEARNED to leave a lot up to God. She’d learned early, when Spencer was a baby, when she first brought the kids to their new house, fresh off a traumatic divorce and a devastating custody battle. She’d taken them to her parents’ first, a single mom feeling like a failure and wondering what had just happened.

For a time that was a refuge for her, but she couldn’t rely on her aging parents forever. She mustered up all her strength and got a job, and with her parents’ help she found a house with room for the kids to roam. The neighborhood had a swim club and a tennis club, all within walking distance. Joyce excitedly pointed it all out to the kids that first day, but when they pulled up to the house, the kids got out of the car looking deflated. To them the house was old and ugly. It was the best Joyce could do with almost no income of her own, but the carpets were worn through, the rooms stank, and the paint was faded. It was a signal to the children that their big bright lives with two loving parents and a big happy home had been blown apart, and this was what was left. An ugly old ranch-style, beckoning them into a new and uncertain world.

But Joyce had a vision. She would turn this place into a colorful home for the kids. It was a mighty burden she had: the three kids and a messy divorce, the children’s father not so far away but mostly out of their lives, finally a new job but as a worker’s comp adjuster for the state, which meant the kind of long days that could wreck you and leave you gasping for air. It meant constant exposure to the ugliest human qualities; the things people do to each other, the things that happen to them. The way wily people manipulated the system to get a buck; the way the system suppressed people in need. Every day she was submerged in desperation, and in greed. She hardened. She began to feel that her whole life prior to her failed marriage and her new job she’d been embarrassingly naïve. She’d always assumed the best in people. That everyone was capable of goodness; that everyone was inclined to act on it.

Not anymore. Now she read bullshit professionally, and her children were beginning to pick up the skill.

When Spencer cried in his room because it was cleaning day—what an emotional child he was!—she gave no quarter.

When she lay in her room and yelled out to Spencer and Everett, “What’s all the noise?!” as long as Spencer said, “We’re just having fun,” even if it was in an oddly pinched, high voice, she let them be.

Of course, she didn’t know that most times, outside on the floor, Everett was sitting on top of Spencer’s chest, holding him by the wrists and making him punch himself, saying he’d swing harder if Spencer snitched. “Tell Mom, ‘We’re just having fun.’ Say it!”

Even then, as far back as when Spencer was a four-year-old, he was picking up on his mother’s skepticism. He had a hard time accepting rules, no matter from what height they came. Joyce took him to church with her, sat him right up front every Sunday, and when the pastor asked who’d like to receive salvation, Spencer raised his hand. Every single week; the pastor smiled every time. “I got you, buddy.” Joyce tried to teach him the scripture. “You don’t need to do it again and again every week!” But the rule didn’t make sense to Spencer, that you only had to do it once. Who decided that? Why was it up to that person? Maybe it was insolence, maybe Spencer just wanted to eat more than his fair share of the savior, but Joyce started to see it differently, that Spencer had a tender heart; her boy wanted to be right with God every week. So she decided to stop fighting. She saved her energy for the fights that mattered.

She pinched pennies and turned the ugly old house into a warm family home, fires always burning when it dropped below fifty, shrubs well tended and grass always mowed. Saturday was cleaning day. She wanted her kids to go out into the world, when they were ready, knowing how to leave it a little better off than they found it. Having won custody, she tried to raise them herself, to keep the kids safe and fed and help them with their homework. And daily she felt she could use an assist, so she looked up and asked God for his favor. She did it in times of particular struggle, or particular need, but also when an opportunity presented itself, like when the couple next door started talking about moving out, and Joyce recognized a chance. She went around the property and found strategic places to pray, conveying upward her preferences for the next tenant. Ideally a single mother like her, please, because it’d be nice to have someone to commiserate with. Ideally one with children the ages of her own, so that the children’s social lives might improve, without Joyce having to drive them more.

And he answered, proving his grace in the form of a young mother coming off her own divorce with two kids in tow and one in her arms. Spencer’s sister, Kelly, took the new neighbors flowers from the yard to welcome them, and then came trotting back, bubbling over with excitement. “Mom, she’s kind of like you!” Joyce invited the woman over for coffee, and the instant they began talking, Joyce’s eyes widened with surprise. “You used to be a flight attendant too?” Joyce had traveled the world that way, and Heidi had as well. The country too. Heidi had worked for a bus company before that. She laughed. “Guess I’ve always been in the travel business,” and her latest trip had brought her right here to Joyce. As they spoke, a series of uncanny coincidences revealed themselves, and the two women talked over each other.

“You adored your parents too?”

“You worry about being overprotective of your boys?”

“You also look back, a little embarrassed at how naïve you used to be?”

Joyce had been delivered a replica of herself. The only difference was Tom, a rock of a man whom Heidi had started dating, and who took to her kids like they were his own. He plied them with pizza and Chris Farley movies, had a good job, and was so obviously a strong man with a good soul. But Heidi was reluctant to take the plunge with him, she said; she didn’t want to marry right away because she still didn’t trust herself after what she’d just put her kids through. But he was there, a stand-in father for her kids, and soon for Joyce’s too.

The two became like sisters; their two houses became two wings of the same estate. They might as well have had no doors or walls because the kids moved through them so freely. Joyce was sure the Lord had something to do with it, that it was he who deserved the credit for this new friend. Or perhaps more accurately, he deserved most of the credit and Joyce perhaps just a little bit of gratitude herself, if you please, for having thought to ask him in the first place, thank you very much.

They were two pillars leaning in on one another, doubly strong. Each was exactly what the other needed, at exactly the moment each needed the other the most. They were both strong-willed and wise, but both in desperate need of support, and for someone with whom to let her guard down, because the kids needed stability after what they’d been put through. Each woman felt guilty. Each felt the need to subdue her own feelings for the sake of the children, because what the children needed was a dependable parent, not an emotional one. It was only with each other that each could let down her guard and admit to even having feelings.

Joyce and Heidi filled a missing piece for one another, and as if that wasn’t enough, their children were just the right ages. Joyce’s son Everett was still the oldest, and Heidi had Solon, the youngest of the new crew, but Heidi’s son Peter was Kelly’s age, and Heidi also had a young son who, it turned out, was born within a few months of Spencer. A quiet child with an occasional flare for the dramatic. She’d wanted to call him Alex, for Alexander, a good Greek name like her first son Peter’s, but when a speech therapist next to her at Lamaze class pointed out it was hard to say the s in Skarlatos after an x, Heidi decided to tweak it. He would be Aleksander. People would call him Alek.

Spencer and Alek became as close as their mothers; they were always together. Alek was usually quiet, a reserved child, but he had a sense of humor and of self-expression that came out in the most unexpected ways. A fleeting obsession with Batman during which he wore a Batman muscle costume all day, every day, for months, even out on errands with his mom, earning compliments from cashiers and supermarket stock boys.

He played a tin soldier in the church’s Christmas production, done up with the full French-style moustache, drawn on with a makeup pen. When an audience member came up to him after the show and kneeled down to congratulate him, the six-year-old Alek looked up and considered the man. He frowned, then he said, “So do you want my autograph?”

Alek was still water running deep, picking up and feeling more of what went on around him than he let on. A barbeque Joyce and Heidi held ended early when the police showed up at Heidi’s door, claiming they were responding to an emergency. Joyce looked at Heidi, who raised her eyebrows—she didn’t know of any emergency. It took half an hour for the moms to find out that Alek, who hadn’t been getting enough attention during the festivities, had decided to call 911 and report a crime in progress. Alek explained to Spencer, who defended his friend; Alek was guilty only of laziness, not sabotage. He’d picked up the phone at Spencer’s house to make the fifteen-foot phone call over to his own, but his finger slipped when typing the 916 area code. An honest mistake!

Or like how well Alek understood Spencer. Spencer’s favorite topic of conversation during his first five vocal years was his own birthday. Without letting on, Alek picked up bits and scraps of things Spencer said about it, and then, when it was finally time to bake a cake for the neighbors, Alek asked Heidi if he could be in charge. He dragged her to the toy store, made her buy three plastic army men and a tiny American flag, and wedged them into the top of the cake in a loose approximation of the marines at Iwo Jima.

Spencer walked into the kitchen on his tenth birthday, saw the cake, looked over at Alek, and then smiled, overwhelmed by the feeling that never before in the whole grand course of human history had a more perfect gesture been performed by one friend for another.

ALEK SITS NEXT TO HIM, looking out the window. Spencer is slumped in his seat, feeling himself beginning to fade. He takes a photo of the laptop on the tray table, the half-sized bottle of red wine, and posts a picture: “First Class Baby!”

Then his eyelids go heavy, and he leans back to bask in the wonderful, heavy swaying, slipping in and out of much-needed sleep.

Soft, reassuring motion, R&B on the noise-canceling headphones. He does not know how long he’s been asleep when there is a moment of foggy disruption, a distant jangling behind the music. Body in uniform at full sprint across his vision, the half realization that he is waking up, tumbled headlong into a movie scene already under way. Headphones off. Eye contact across the aisle, Anthony’s face screwed up in confusion.

Now he is fully awake and crouched between the seats. A gate in his brain has lifted, and a tidal wave of adrenaline is crashing in; his muscles tighten and time decelerates for him. He sees a glass door slide open, a skinny man with an angry face wearing a backpack the wrong way, strapped to his stomach, and somehow Spencer knows without having to think that the bag is full of ammunition and swung to the front because that way it’s easier to reload. Spencer can hear the footfalls as clear and loud as if the man was stomping on purpose; he steps forward, reaches to the ground, and picks up a machine gun that for some reason is lying there. He lifts it up, and Spencer can hear the metal-on-metal cha-chunk of the weapon being cycled.

A beat passes. Someone has to get this guy. A sliver of frustration sparks off something in his brain. I’m gonna die here—then an electrical charge surges through his entire body and one more final thought tumbles home with a flood of energy, a notion stored away from a classroom at Fort Sam two years ago that his brain now accesses like a hard drive retrieving a kernel of information: I am not going to die sitting down. The realization verges on euphoria. Sound compresses so he no longer hears the screams, and the shattering glass he only now understands is what woke him filters into a thin and distant memory, like the noise itself has been sucked from the train into the past and now all he hears, the only noise in the entire world, is heavy, clomping footsteps. The terrorist is getting closer. He hasn’t started shooting yet.

Spencer gets up and starts running. Alek’s voice comes to him as encouragement from another universe, cheering him on: “Spencer, go!” and Spencer locks eyes with the terrorist; then his vision narrows, his more extraneous senses leave him. He does not register sound at all, his peripheral vision collapses, and he can see nothing but a small part of the man he is charging, a square of fabric, and he aims for that.

He realizes that he is totally exposed.

There is no cover.

There is no other distraction for the shooter because everyone else is crouching.

He is a big, easy target. He is exposed for one second, two seconds, Here is where I die, three seconds, four seconds—the terrorist cocks the gun back again, lowers it at Spencer, and as Spencer pumps his legs, he hears with total, focused clarity the shooter pulling the trigger and the firing pin striking a bullet.

Then everything goes dark.

2.

GUNS WERE PERHAPS the only difference between Heidi and Joyce. Spencer had free rein to play with whatever kind of toy he wanted, and his mother had given in to the fact that her boys loved guns, because—well, boys love guns. She had to laugh at Heidi who, bless her, still grasped on to her misplaced hope that Alek and his siblings would grow up in a gun-free household. Good luck, Joyce thought. The two new surrogate sisters established boundaries to deal with the one part of parenting that caused friction. The trash cans between their two houses marked the demilitarized zone: no guns on Heidi’s side.

It was just a few years later that Joyce walked out to see Heidi, waiting in the driver’s seat of her SUV, while a commando team of camouflaged teenage paintballers piled into the back. She was overrun; she’d given up. Joyce couldn’t help herself. “Man, Heidi,” she yelled, “looking good with all that camo!”

Heidi looked out the window, and tried to suppress a smile. Then they both exploded with laughter.

By then Alek and Spencer had formed a kind of impromptu league of war games. They tipped over trash cans in the street and dove behind cars, they gathered neighborhood kids to serve as comrades, lined up on opposite ends of Woodknoll Way, and charged, pelting each other with so many airsoft pellets that the gutters ran neon yellow and green, as if the roads of northeast Sacramento had been drenched by psychedelic rain. Other kids wanted in. Soon there were five to a side, then ten, running kamikaze charges at each other from opposite ends of the street.

There was no strategy at first, then it was just that if you got hit you were out, but how could you prove someone got hit? Arguments broke out, so it grew more intense, then became refereed by a set of unwritten and eagerly disputed rules, veritable conventions at the summit of Woodknoll Way, where two dozen arguing kids hammered out the finer points of make-believe warfare, all in an attempt to even the scales and maintain some sense of fairness. This became especially necessary because Alek began bringing firepower other kids couldn’t compete with. One day he came out to fight with what Spencer figured must be a $150 replica Colt 1911 gas-blowback CO2-powered pistol. Alek could fire rounds at 350 feet per second, so the other kids were diving behind cars and tumbling into hedges while Alek strafed the neighborhood like a pint-sized Tony Montana. Order had to be restored. So they started dividing up teams according to quality of equipment. Alek would be paired with whomever the new kid was who wanted to play but only had some pissant little peashooter.

Down a few streets from the Stone-Skarlatos Forward Operating Base, there was a kind of nature reserve behind the Schweitzer school, where the teachers used to teach things like Albert Schweitzer’s philosophy of reverence for life and peace, but that the boys colonized for the purpose of intensifying their philosophy of reverence for imaginary war. Behind BMX bike platforms and half pipes recast as antitank obstacles blocking imaginary tanks from amphibious landings on an imaginary Omaha Beach, they put on masks and fired off paintballs by the bushel. Paintballs were expensive on an allowance, but better than airsoft because you couldn’t cheat as easily. You could spend less time arguing and more time fighting.

Spencer never got tired of it, and Alek didn’t either; they’d started a little insurgency in their leafy Sacramento suburb; they fought into the night. And Spencer tried to make those days stand still, because even then he had the sense that other forces were coming along to change their lives; powerful forces beyond their ability to control. Something big and hard to see and almost impossible to confront, stronger than just him, which he and Alek would try to weather together, but that would eventually drive them apart. At least for a time.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.

Вы ознакомились с фрагментом книги.

Для бесплатного чтения открыта только часть текста.

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера:

Полная версия книги