The New IQ: Use Your Working Memory to Think Stronger, Smarter, Faster

Dedication

For our little heroes, M. and M.

Note to Readers

Names and identifying details of some of the people portrayed in this book have been changed, and some people portrayed are composites or are created for illustrative purposes.

CONTENTS

Title Page

Dedication

Preface

PART I: The New IQ and You

1. Welcome to the Working Memory Revolution

2. Why Working Memory Is Crucial to Success

3. The Joker in the Mines—How Working Memory Makes Us Happier

4. Failures, Bad Habits, and Missteps

5. The Most Important Learning Tool— Working Memory in School

6. The New Mind-Body Connection—Working Memory in Sports

PART II: Growing and Improving Working Memory

7. Working Memory Across the Life Span

8. Working Memory Training 101

9. Secrets of Working Memory Specialists

10. Feed Your Brain, Fuel Your Working Memory

11. Seven Habits to Supercharge Working Memory … and a Few to Avoid

PART III: The Future and Past of Working Memory

12. Designing the World for Working Memory

13. The Dawn of Working Memory

Footnotes

Bibliography

Working Memory Quick Hits Manual

Acknowledgments

About the Authors

Copyright

About the Publisher

PREFACE

Intelligence That Matters

Does IQ matter? Perhaps it may matter to your school; perhaps to an employer when hiring, but does it really matter to you? This number—somewhere between 85 to 115 for most of us—seems to have lost its significance. Of course, you may be pleased to find that your number is closer to 115, but if you found that it was closer to 85, would you be all that concerned? If you answered “no” or “probably not”, you’re not alone. In an age when nearly any factoid can be had at a few taps of the keyboard, IQ—a measure of intelligence synonymous with the accumulation of information readily available on Google—seems outdated and even quaint in the context of everyday life. Is a 115 going to make it easier for you to cook dinner, help the kids with their homework, and answer the phone at the same time? Does a 115 help you find happiness when things aren’t going your way? Will a 115 help you manage stress or resist the chocolate éclair? Will it give you a compelling response to the surprise question in the interview? The answer is no. The world we live in, the world that matters to us, demands a new conception of intelligence.

This book is about an intelligence that helps you succeed in the small things that comprise the ebb and flow of your life—like adapting a PowerPoint presentation for a new client, negotiating a treaty between warring offspring, and juggling football practise with the new product deadline. This intelligence is also deeply implicated in those meaningful moments as well, like when you were tongue-tied upon meeting the love of your life, or when you controlled your panic and found your five-year-old in the toy section, or when you came to accept the loss of a job and took the first step toward a new career. This book is about intelligence that matters.

PART I

1

Welcome to the Working Memory Revolution

IN DECEMBER 2005, a broker on the Tokyo stock exchange sold 610,000 shares of a company called J-Com, for the low, low price of 1 yen, an amount less than a penny. The problem is that he meant to sell one single share for 610,000 yen. Epic oops. In 2001, a London dealer sold 300 million pounds sterling’ worth of shares when he intended to sell only 3 million pounds. The trade sparked a panic in the market that caused 30 billion pounds to go up in smoke.

Brokers may process mountains of information when deciding what to sell and buy, but in the heat of the moment, all it takes is just one extra piece of information—the ring of a phone, the flash of a screen, the thrill of being responsible for such a large sum of money—and their focus is lost. No longer able to process all the information, they struggle to check orders carefully. Trading is a profession that places high demands on a foundational cognitive skill called working memory.

By working memory advantage, we mean that this skill gives you a leg up, a boost in life. As you will discover, working memory offers you an advantage in a huge range of activities: from the everyday, like giving an important presentation at work, to the extreme, like ripping down an eighty-foot wave. It helped our evolutionary ancestors to advance from just surviving to thriving. It enabled our technological trajectory: from a bone club used for bashing to an iPhone used for connecting. By ignoring, overloading, or undermining your working memory, you put yourself at a huge disadvantage. But by focusing on your working memory, taking it into account, and improving it, the sky’s the limit. We wrote this book in order to give everyone an opportunity to take advantage of this life-changing skill.

In the past decade, research on working memory has exploded. It is fast emerging as one of the most widely researched cognitive functions of the twenty-first century, and we have been leading participants in much of this research. Tracy developed a groundbreaking and highly accurate standardized working memory test for use by educators and has dedicated much of her research career to investigating the role of working memory in education and learning difficulties. Ross has focused his attention on developing exercises to improve working memory, and as the CEO and founder of Memosyne, Ltd., he developed working-memory-training software called Jungle Memory that has been used by thousands of students. Together, they have examined the role of working memory in a variety of contexts, such as how it changes when you get older; how it is linked to happiness; how it relates to lying; how it is affected by activities like barefoot running; and how it is influenced by social media like Facebook.

What Is Working Memory?

Working memory is our ability to work with information. More precisely, working memory is the conscious processing of information. By conscious, we mean that the information is on your mind. You are giving attention to it, shining a mental spotlight on it, concentrating on it, or making decisions about it. You are also intentionally ignoring everything else. If you are thinking about a stock trade, for example, you are filtering out the ringing phones, the jabbering of your coworkers, and the excitement of placing a $1 million order. By processing, we mean that you are manipulating the information, working with it, making calculations with it, or reformulating it.

The classic example of a job that requires a strong working memory is that of an air traffic controller, whose job is to maintain the safe and orderly flow of air traffic. With hundreds of planes taking off and landing every hour, an air traffic controller must have the mental agility to process multiple variables, such as equipment, weather patterns, traffic volume, precise communication with pilots, and quick calculations. In times of emergency, they must be able to make split-second decisions while effectively moderating the stress of knowing that the lives of pilots and passengers are in their hands.

We see a strong working memory giving us an advantage at play in many aspects of everyday life too. It allows you to listen to your spouse while checking your smart phone and making pancakes for the kids. It lets you complete a complicated spreadsheet in spite of interruptions from your constantly ringing phone and the din of annoyingly loud coworkers. Working memory gives you the ability to remain focused on the conversation with your dinner date while ignoring the urge to check the hockey score on your mobile.

Working Memory in the Brain

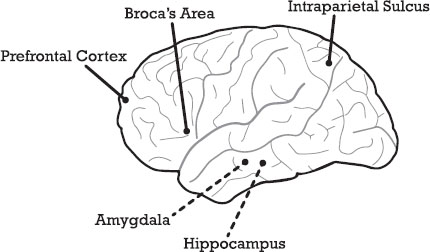

For more than the past decade, scientists have been using advanced brain imaging to examine how working memory functions in the brain. Their results reveal that using working memory involves a number of areas in the brain. On the next page are some of the major players:

Major Players in Working Memory

Prefrontal cortex (PFC): The PFC is the home of working memory. Located in the front of the brain, the PFC coordinates with other areas of the brain through electrical signals and receives information from those regions so your working memory can make use of it. Brain-imaging scans show that when working memory is being used, the PFC glows while it fires thoughts to and works with information from the different brain regions. Working memory is the primary function of the PFC. Though the PFC is the area most often associated with working memory, it is important to note that scientists have also found activation in other areas of the brain, such as the parietal cortex and the anterior cingulate, when people perform a working memory task.

Hippocampus: The hippocampus is where the vast amount of knowledge you have acquired over your lifetime is housed for long-term storage. It is the location of long-term memory (LTM). Your working memory allows you to sift through all the information you have stored in your long-term memory, and pull out the bits most relevant to the task at hand. It gives you the ability to combine that stored knowledge with new information coming in, and to put new information into your long-term memory.

Amygdala: The amygdala is the brain’s emotional center. When you are experiencing a strong emotion, like fear, your amygdala is activated. Working memory is also important to emotional control, managing the emotional information coming from the amygdala and preventing it from distracting you from the task you’re working on. If someone yells “Fire!” in the cinema, your working memory would help you to control the fear coming from your amygdala so that you can exit in an orderly fashion without creating a panic.

Intraparietal sulcus: Located at the top back portion of the brain, the intraparietal sulcus is the brain’s math center. When you need to perform calculations, such as in choosing the best mortgage loan or guesstimating how many more miles you can go on a quarter tank of gas, your working memory relies on it to get the answer. In fact, the intraparietal sulcus is so important to math skills that when researchers used mild electrical currents in order to take it offline, participants struggled to perform simple math tasks, like deciding whether 4 was bigger than 2.

Broca’s area: Situated on the left side of the frontal lobes, Broca’s area is involved in language comprehension and verbal fluency. Whenever you are writing or interacting with friends, family, colleagues, or a love interest, your working memory is processing information sent from this area. Whether you are a quick-witted verbal gymnast or you tend to stumble over your words depends in part on the strength of your working memory. We recently saw this play out at a wedding when the best man stood up to give the toast and then realized he had left his notes in the car. Instead of stumbling over a bunch of “ums” and “uhs,” his working memory and Broca’s area worked together to help him craft an eloquent, heartfelt toast on the spot.

What Working Memory Is Not

Whenever we give a presentation about working memory, someone in the audience raises his hand and asks, “Isn’t that the same as short-term memory?” The answer is an unequivocal no. Short-term memory is the ability to remember information, such as someone’s name at a party, this person’s occupation, or the title of a recommended book, for a very short period. We usually don’t keep this information in mind for long—a few seconds or so—and we would typically struggle to recall that person’s name or the book title the following day. Working memory gives us the ability to do something with the information at hand rather than just remember it briefly.

Let’s say you’re at a business event and you meet Keith, a small-business consultant who mentions that anybody trying to start a business absolutely must read The Essential Entrepreneur by Smarticus McSmarty. You instantly recall that your friend Theresa is thinking about launching a new business venture, and you jot down the book’s title so you can send her a text about it later. Your working memory is what helps you recall, from long-term memory, that Theresa wants to start a business and combine that with the new information that the book is great for entrepreneurs.

Working memory is also different from long-term memory. Long-term memory is the library of knowledge you have accumulated over the years—knowledge about countries, information about random news facts, memories about events from your school days, and even those annoying advertising jingles you heard on TV when you were a kid. Information may remain stored in your long-term memory for anywhere from a few days to many decades.

Working memory is what allows you to access that information and put it to good use. You can pull out information from your long-term memory, use that information in the moment, and then file it away again. Working memory is also the mechanism used to transfer new information into long-term memory, as when you are learning a new language.

Working Memory as a Conductor

You can think of working memory as your brain’s Conductor. A conductor of music brings all the different instruments of an orchestra under control. Without the conductor, the result is a cacophony: the piccolo might tweet when the piano was supposed to play or the violins might be drowned out by a thundering percussion section. When the conductor walks out on the stage, chaos is brought to order.

In a similar way, your working memory gives you the advantage of control over the daily information onslaught: the emails, the ringing phones, the schedule that is constantly changing, the new math lesson that must be learned, your friend’s disheartening Facebook update, the Twitter updates, the presentation that must be rapidly assembled for a potential client. In this ocean of information, where everything seems to be equally important, your working memory Conductor has two main functions:

1 It prioritizes and processes information, allowing you to ignore what is irrelevant and work with what is important.

2 It holds on to information so you can work with it.

Throughout this book, we occasionally refer to working memory as the Conductor, or the working memory Conductor, when discussing these functions.

For an illustration of how the working memory Conductor can give you an advantage at work, imagine for a moment that you are Mark, a middle manager in Microsoft’s Tablet PC division, and the Tablet has been taking a beating from the iPad 700, which projects holograms. iPad 700 users love seeing their pictures and spreadsheets in three dimensions. You’re called to a meeting where an inventor takes out a tablet called the FeelPad that can give holograms mass. FeelPad users can project images that can be touched and felt, not just seen. You are truly amazed. And because you are lower down the pecking order, you can just sit back and be enthralled because no one ever asks you a question at these meetings. Until today.

Bill Gates turns and looks directly at you. “Mark, will this give our tablet an edge?”

It is at this moment that you realize Gates mistakenly thinks you are the product manager. Your amygdala, the emotional heart of your brain, surges with terror. You can correct him, but then you know your career won’t go anywhere. Or you can go with the flow and see where it leads. The Conductor takes over, and you decide to take a risk. Because you don’t know much about the FeelPad’s technology, you have to work with what you have just heard and cobble together an answer that combines the key features of the technology and how you think it will fit into the marketplace.

“Well,” you say, “I think that the brand recognition of the iPad 700 is so formidable that it will mean considerable financial investment to make a dent in Apple’s sales, but if the FeelPad can really make projections come to life, we may have a real iPad killer on our hands.”

“Great,” says Bill. “Apple wants to look at the technology too, and the inventor is giving us one day to make an offer. You have ten minutes to decide if we need to buy it.”

Ten minutes? You go back to your cubicle to formulate a plan. That isn’t enough time to come up with a detailed proposal, but it is enough time to assemble the most important technological information, market analyses, programming issues, and budget projections. Shutting out the ringing phone, the blinking email notice, and the low-level chatter, you modify a product launch plan with which you are already familiar and show that with the right software and viral marketing programs, the FeelPad can crush the iPad 700. Bill likes your plan so much that he makes you the project manager, and within a year, the FeelPad single-handedly turns around Microsoft’s fortunes and you are promoted to vice president of new product development. Congratulations!

This remarkable change of fortune is a consequence of your Conductor working at optimum levels. It allowed you to pull out relevant information that you already knew, like product launch plans, and allowed you to synthesize it with the potential requirements of the new device. It also kept you on task and blocked distracting information, such as the ringing phone, the office chatter, and the surging fear that you may blow this opportunity. It allowed you to keep in mind the hardware, software, and finance data. It also allowed you to hold on to the information long enough to structure your plan.

What Working Memory Helps You Do in Your Daily Life

Working memory gives you the advantage of managing information in your day-to-day life from the time you’re born until your golden years. Here is a quick preview of just a few of the many ways it helps you. We will explore many of these in much greater detail throughout the book.

Prioritize Information

A strong working memory helps you manage the stream of emails, texts, Facebook status updates, Tweets, and phone messages pouring into your life. Your Conductor allows you to process and prioritize all those data so you can quickly respond to the most important things first, make a mental note to deal with some things later, and efficiently shuffle the junk to the trash.

Focus on the Important Stuff

Life is filled with disruptions, and working memory helps us pay attention to what really matters. Torkel Klingberg of the Karolinska Institute in Sweden found that one of the important features of working memory is to selectively filter out distractions so we can focus on relevant information. For example, as we were putting the final touches on this book, we had a small electrical fire, our car died and had to be towed away, our refrigerator threw in the towel (resulting in mild food poisoning), and our babysitter had to take the entire week off due to a family emergency, leaving us with two rambunctious boys clamoring for our attention when we were supposed to be working. Working memory helped us deal with the emergencies, create a schedule to watch our sons, and then quickly shift our attention back to the book so we could finish and click the send button in time to meet our deadline.

Think Fast on Your Feet

You’ve got an interview for your dream sales job, and you are totally prepared for it—you’ve researched the firm, its clients, its competition, and its sales strategies. But the interviewer throws you for a loop with a wacky question out of the middle of nowhere: “You’re meeting a client in an industrial estate with a gated parking lot. Where do you park?” “Huh?” You hesitate, then your working memory digs into your recent memory vault to recall that the interviewer had pointed to her car—backed into the parking space next to the exit gate—during your interview, and you quickly figure that where she parks is where she would want you to park, so you say, “I’d park right next to the exit.” Ding, ding, ding! You get the job.

Take Smarter Risks

Your Conductor helps you zero in on the most essential information when weighing the pros and cons of any potentially risky venture and helps keep you from blindly going with the flow or following the crowd. For example, when that Facebook initial public offering you invested in takes an immediate nosedive, it’s your working memory that helps you decide whether to dump your stock or hold on to it.

Learn More Easily in School

Kids use their Conductor every time they set foot in the classroom. It helps them to inhibit distracting information—like their classmates whispering near them—and to keep track of where they are in multistep tasks. It also allows them to access all the information they need, such as numbers or words, to complete an assignment. And, it lets them hold that information in mind and complete the tasks as quickly as possible.

Make Judgment Calls

Making quick decisions about your likes and dislikes, as well as how to act in certain situations, is a working-memory-intensive task. It may come as a surprise that even judging attractiveness relies heavily on working memory. When you spot someone across a bar, your working memory riffles through your hippocampus Rolodex for previous references of beautiful people. Then your working memory allows you to hold this information in mind while you compare the new person with the mental image and make a decision: Hot or not? The same process occurs as you decide whether you like a horror movie. Does the monster on screen measure up to the others stored in your hippocampus?

As far as actions go, your working memory is in control. If you get into a car accident and the other driver jumps out of his car and starts coming toward you in an aggressive manner, your working memory helps you quickly run through various scenarios to determine whether it’s better for you to get out of the car or lock your door and call 911.