Collins Complete Hiking and Camping Manual: The essential guide to comfortable walking, cooking and sleeping

Head out or head in? Some people like to pull the hood drawcords so tight that only their nose is sticking out. This makes me feel a little claustrophobic, so I’m a head-outer. But that makes me colder, so I bring a good fleece hat. When bugs are about, I use a mosquito head net.

SLEEPING PADS

Sleeping pads serve two functions: comfort, cushioning your body from rocky ground; and more important, insulation. In cold conditions, a sleeping pad is essential to maintain your body heat by preventing conductive heat loss to the colder ground. Sleeping pads come in two basic types: closed-cell foam such as Ensolite or inflatable pads such as Therm-A-Rest pads. Closed-cell foam pads are lightweight and roll up to a small diameter. They tend to get a little stiff in cold weather. Inflatable pads are typically open-cell foam covered with coated nylon and have an inflation valve at one end. Some people feel that inflatables are more comfortable, although they tend to be a little slippery—tough if your tent is pitched on a slope. With inflatable pads you should carry repair items (good old duct tape) to patch any holes that develop in the nylon outer layer. A leaky inflatable is almost useless.

For three-season camping, a pad that is 3/8 inch thick (10 millimeters) is adequate. In colder conditions, you should have 1/2 inch (12 millimeters) of insulation between you and the ground. Pads are available in either full length or partial length (three-fourths or two-thirds). You can save weight by not using a full-length pad. Full-length pads are essential only in very cold environments, so that no part of your sleeping bag is in contact with the cold ground.

You can cut down on sleeping bag weight in a couple ways: fill and features. Going with a “superlight” synthetic fill or a down bag will decrease the weight for a particular temperature range of bag. For warm weather camping you don’t need features like draft tubes that add weight. You can get 40°F (4°C) sleeping bags that weigh 2 pounds (4.4 kilograms) or less.

While I like the comfort of an inflatable pad, and there are ones that are very light, I think a foam pad is actually a better choice in an ultralight setting. Foam pads have many more uses than just insulating your body from the ground. If you are carrying a frameless rucksack, your rolled foam pad can create the “frame” for additional support. In first-aid situations, they can be cut up for splints; you can pad your blistered heels with them; insulate pots from the cold ground; and on and on.

SHELTER

When planning your trip, you need to know whether you should bring your own shelter or there will be shelter options available on a daily basis along the trail. If you need to bring your own shelter, there are a number of options:

Tarpaulins Pro: Lightweight. Inexpensive. Less condensation. Con: Not as weatherproof as a tent. Does not provide bug protection. May require trees to set up.

Tents Pro: Good weather protection. Good bug protection. Con: More condensation. Heavier. More expensive.

GENERAL SHELTER TIPS

Whenever you use a tent or tarpaulin, think carefully about site placement so that you leave no trace. A tent or ground sheet on grass for more than a day will crush and yellow the grass beneath, leaving a direct sign of your presence. Stakes can damage fragile soils, and guylines and tarpaulin lines can damage trees.

Find a resilient or already highly impacted location. Try to find a relatively flat location; hollowed-out areas pool water in a storm.

If possible, identify the prevailing wind direction and set up your tarpaulin or tent accordingly. If rain is a possibility, set up so that the openings don’t face the oncoming wind.

TARPAULINS (TARPS)

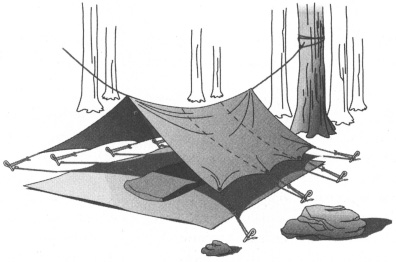

Tarp setup can be an art. You typically use a ground sheet underneath to provide a floor and protect your sleeping bag and gear from wet ground. You need trees located an appropriate distance apart in order to set up a tarpaulin, although you can also rig a tarpaulin from overhead branches or trekking poles. There are many variations, but the most weatherproof is the basic A-frame.

A-Frame Tarpaulin Setup

Select an appropriate location in your campsite to set up your tarpaulin (see page). Have a tarpaulin line of sufficient diameter (1/4 inch or 6 millimeter braided nylon) to prevent knots from slipping.

Tree Method Secure one end of the tarpaulin line to a tree using a bowline knot (see “Bowline,”) at an appropriate height for the size of your tarp, and stretch the running end to the other tree. You can set your tarp line height so that the bottom edges of the tarp will lie several inches/centimeters above the ground sheet, allowing for ventilation, or wrap the edges of the tarp under the ground sheet for better weather protection (but less ventilation).

Wrap the running end of the tarpaulin line around the second tree and tie it off using an adjustable knot such as a tent hitch or a lorry hitch (see “Tent Hitch,” “Lorry Hitch,”). This will allow you to set and later reset the tension of your tarpaulin line. To tighten the tarpaulin line, simply slide the tautline hitch or pull on the trucker’s hitch and tie it off. The tautline hitch is preferred since it can be easily retensioned.

Place the tarpaulin over the tarpaulin line and stake out the corners of the tarpaulin at 45 degree angles. This can be done using stakes or by tying the guylines to rocks or other trees. Make sure the tarpaulin is adequately guyed out so that strong winds won’t tear it down. Or you can fold the edge of the tarpaulin underneath the ground sheet and weigh it down with rocks on the inside to create a very rainproof shelter.

Pole Method If you don’t have trees available, you can use sticks or trekking poles at either end of the tarpaulin. Stake out the four corners of the tarpaulin at 45 degree angles. Raise the pole at one end of the tarpaulin and either use two half-hitches (see page) or a simple tension wrap around the top of the pole, then run the guyline down to the ground and stake it out. Do the same on the other side. You will need to make sure both ends are staked down well and the entire line is under tension in order to properly support the tarpaulin. Some tarpaulins have side lifters that, when guyed out, prevent sagging and increase headroom under the tarpaulin.

A-Frame Tarpaulin

Tree Method A simple tarpaulin setup is to locate the entrance next to a tree and guy the center point onto the tree while guying the front corners out. The rear end can be staked out with a pole or stick for more ventilation or flattened out to reduce the number of stakes and lines needed.

Tarpaulin Tips

To prevent rainwater from running down the tarpaulinline into the tarpaulin, tie a bandanna on the line just outside the tarpaulin. It will redirect the water drips to the ground.

You can create your own grommets for guylines by placing a small stone on the inside of the tarpaulin and tying parachute cord around it from the outside. The free end of the parachute cord can then be staked out. This is useful if grommets are broken or if more support is needed for the tarpaulin.

Rain ponchos can be used as makeshift doors to prevent wind and rain from blowing in through the ends of the tarpaulin.

If there aren’t trees around, try boulders, rock outcroppings, or other objects to string up your tarpaulin.

TENTS

A multitude of tents are available—everything from simple A-frames to complex geodesic domes. When selecting a tent, consider the following:

The size of your group and how many people each tent sleeps.

Freestanding tents are generally preferred over nonfreestanding tents. A freestanding tent has a pole arrangement that maintains the tent’s functional shape without the need for guylines. However, in windy conditions nothing is really freestanding, so all tents come with guylines and you should be prepared to stake the tent down and stake the sides out.

Single-wall Tent versus Double-wall Tent. Most tents use a rain fly—an outer waterproof layer that is separated from a breathable layer beneath. This double-wall system allows moisture inside the tent to pass through the breathable layer and then escape, reducing condensation in the tent while the waterproof layer overhead keeps rain out. It also helps provide better insulation by increasing the layers of still air. There are also single-walled tents. Some are completely waterproof and rely on ventilation systems to reduce condensation inside the tent. Others are made of waterproof–breathable material. A single-wall tent will be lighter than a comparable double-wall tent. Single-wall nonbreathable tents are prone to interior condensation.

Examine the floor space of the tent and the usable internal volume. Dome-style or arch-style tents typically have greater usable overhead space than A-frame tents.

What season(s) the tents are designed for. Summer tents are double-walled tents with much of the inner breathable layer being mosquito netting. They are lightweight and allow for lots of ventilation in hot weather. Three-season tents do well in three-season conditions but are not sturdy enough to take heavy snow loads. Convertible tents are four-season tents where you can leave off some poles to make the tent lighter. Four-Season tents have stronger poles and are designed to be able to withstand snow loading. They can also be used as three-season tents but weigh more.

Fastpack tents have a tent fly that can be rigged with the poles and attached to a tent footprint as a floor, leaving the rest of the tent at home. Basically you are building a tarpaulin and ground sheet with poles. This is a nice feature to look for when buying a tent as it allows you to cut down on weight when you don’t need a full tent.

Tent Tips

Each tent comes with its own set of instructions. Practice how to set up your tent before your trip so you can do it in the dark, in bad weather, or in bad weather in the dark. I set up mine at home the first time to get to know the tent, then try to do it outside at night with a headlamp.

Make sure you bring pole splints or extra poles with you in case a pole breaks.

Make sure that you have the right tent stakes for your environment. Ever try to hammer one of those narrow wire tent stakes into rocky soil and watch it bend at a right angle? Lightweight/strong steel or titanium stakes are much better than the cheap aluminum ones. In soft surfaces like sand or snow, you will need a stake with a much greater surface area (especially for sand). In snow, you can create a “dead man” by tying your guyline to a branch and then burying the branch in the snow and packing the snow down on top. When the snow sets, the dead man will be solidly fixed. (You may have to chop it out when it’s time to go.) In sand, fill a stuff sack with light bulky items, tie your guyline to it, and bury it.

Use a tent ground sheet, a space blanket, or a tarpaulin to help protect your tent floor from rips and tears (better to put a hole in the cheap tarpaulin than your expensive tent).

Always stake your tent down if you are going to be in windy areas or will be leaving your tent during day excursions.

Avoid cooking in a tent. The material most tents are made of is flammable, and the water vapor from cooking leads to extensive condensation inside the tent. Carbon monoxide gas released from a burning stove in a confined space like a tent can lead to suffocation and death. (See “Carbon Monoxide,”.)

If you are going ultralight, the first question is, Do you need a shelter at all? If you are on a trail like the Appalachian Trail designed for through-hikers, there will be shelters at hikeable mileages for the entire trip. Of course, you can’t be sure that you can always make the mileage, so you should carry a basic tarpaulin or bivy sack as an emergency shelter, but you don’t need to carry a full tent.

If you are bringing a shelter, there are a number tarpaulins that weigh under a pound (454 grams) and some superlightweight tarpaulins weighing less than 8 ounces (226 grams). Ultralight tarpaulins are often made of silicon-impregnated nylon (sil-nylon). This is one of those lightweight fabrics that takes care to keep from puncturing or tearing it. There are also ultralight tents from companies like Big Agnes, GOLITE, Mountain Hardware, MSR, and Sierra Designs that weigh under 2 pounds (900 grams).

COOKING EQUIPMENT

Basic cooking gear is listed in the general equipment list on pages, but here are a few necessary items:

Pots It’s best to bring at least two pots. A pot set that nests is easiest to carry. The pot size depends on the size of your group: for one to three people, use a 1.5-liter and a 2.5-liter pot. For groups of six, try a 2-liter and a 3-liter pot, and for eight or more, go with at least a 2-liter and a 4-liter. Pots should have lids that seal well. Flat lids allow you to build a small fire on top of the lid for baking. Having a rim on the outside of the pot is essential for picking it up with a pot-gripper. Stainless steel pots weigh a little more than aluminum but will last longer. There is a great debate about pots with nonstick coatings. The nonstick coating makes it easier to clean the pots, but you can’t use harsh abrasives to clean them, which eliminates some of the best natural cleaning materials, such as sand.

Frying pan One per trip is usually plenty. Choose your size based on the size of your group (or how big you like your pancakes). Frying pans are generally available in 8-, 10-, and 12-inch models. Using a frying pan with a cover will reduce your cooking times. A pot cover that fits your frying pan saves weight.

Utensils Lexan plastic utensils are basically indestructible. Be careful cleaning them. Harsh abrasives can create scratches that will hold dirt and bacteria.

Titanium is lighter than either steel or aluminum and just as durable. You can cut down on weight by using titanium cooking pots, cups, fry pans, and utensils. The only drawback is that titanium items are significantly more expensive. For solo hikers, bring only one small pot and lid. A spoon is the only utensil you’ll probably need.

BACKPACKING STOVES

There are three basic types of backpacking stoves based on what they burn: liquid fuel, compressed gas in a canister, and stoves that use solid fuels like a fuel pellet or wood. Most backpackers rely on liquid fuel stoves.

Liquid Fuel Stoves burn Coleman fuel (a.k.a. white gas), kerosene, or alcohol. Pro: Fuel readily available (alcohol and kerosene available worldwide). Con: Require more maintenance. Some stoves don’t simmer well. Alcohol doesn’t burn well at high altitude (over 7,000 feet or 2,133 meters).

Compressed Gas Stoves burn butane, isobutane, or propane. Pro: Easy on and off. Low maintenance. Easy to control temperature. Both the stove and the fuel canister are lighter than liquid fuel stoves. Con: Don’t work as well at colder temperatures. Difficult to tell amount of fuel left. Disposal of pressurized canister. Butane doesn’t burn well at high altitude (over 7,000 feet or 2,133 meters).

Solid Fuel Stoves burn flammable pellets or wood. Pro: Easy on and off. Practically zero maintenance. Con: Pretty much either off or on, hard to control temperature. Small, hard to use for large group cooking.

How Petrol/Kerosene Liquid-Fuel Stoves Work

The fuel is stored in a separate tank. In most cases, this tank uses a pump to help pressurize the stove. The tank should be filled only to the ¾ point, leaving some air in the tank. The pump forces air through a one-way valve into the tank, increasing the pressure inside. Opening the fuel flow valve allows the pressurized liquid fuel to flow from the tank through the fuel line to the generator tube that passes over the stove burner and back to the base of the stove, where it comes out a small opening called the jet and into the priming cup. Initially, vent only a small amount of fuel into the priming cup, then shut off the fuel flow valve. When you light this small amount of fuel, it will heat up the generator tube. This process is known as “priming the stove.” It can also be accomplished by using a separate priming source such as alcohol or priming paste. Once the generator tube is hot, the fuel flow valve can be opened and the stove burner lit. The pressurized fuel from the tank flows through the heated generator tube, where it is vaporized. The fuel that now flows through the jet is vapor. It strikes the flame spreader on the burner and ignites. The flame spreader redirects the flame from a single, vertical “candle” flame to a wider flame for more efficient heating. When the stove is properly primed, you should see a blue flame similar to that on a gas range. If the flame is yellow or orange, it means that the fuel is not being completely vaporized in the generator. As the generator heats up further, it may begin to run properly, or you may have to turn off the stove and reprime it. (See page for detailed sample instructions.)

Lighting Other Stoves

Alcohol Stoves Alcohol stoves don’t require any priming. Because alcohol doesn’t have the explosive combustible properties of petrol, it doesn’t need to be vaporized in order to burn. You just pour the alcohol into the burner container and light it. You can burn either denatured alcohol or grain alcohol (ethanol). In cold temperatures you may have to warm up the alcohol (by putting it next to your body) before lighting.

Compressed Gas Stoves The fuel canister has a screw attachment on the top. The stove burner either screws directly onto the top of the canister or the burner sits on the ground off to the side and there is a flexible fuel tube that runs from the burner to the fitting on the canister. Once the canister is connected you simply turn the fuel knob to ON and light the stove.

Solid Fuel Stoves This varies from stove to stove depending on the type of solid fuel. With a pellet stove like the Esbit, the fuel pellets are flammable. You insert the pellet into the stove and light it. The pellets will light even when cold or wet.

Stove Safety Guidelines

Know how to operate a stove properly before you light it.

Make sure your stove has enough fuel before you light it.

When cooking on a stove, always work from the side where the on/off control is located. Never reach over the stove to work on it or put your face or body directly over the burner.

Do not overfill a liquid fuel stove.

A windscreen will help the stove work more efficiently and save fuel as well as keep the flame from being blown out.

If using a stove with a separate fuel bottle, make sure that the fuel bottle is designed to hold pressure (such as MSR bottles). Also make sure that the bottle is in good shape. I’ve seen plenty of banged and dented fuel bottles that I just don’t trust to hold pressure. These should not be connected to a stove.

Be careful if a hot stove goes out. Do not relight it until it has cooled down for at least 15 minutes. Priming a hot stove with fuel can result in instantaneous and violent ignition.

Never use a stove inside a tent, snow cave, or other enclosed or poorly ventilated space. Stoves give off carbon monoxide, which could lead to asphyxiation in a poorly ventilated area (see “Carbon Monoxide,”).

Fuels should always be stored a safe distance from the stove when it is being used. Care should be taken to note the wind direction in relation to the fuel storage area so that fuel fumes cannot reach the flame source or sparks reach the fuel source. Always refill stoves far from any source of flame or heat.

What to Do if Your Stove Catches Fire

I’ve seen a number of models of stoves leak and catch fire. The first thing to do is to back away quickly. The best methods for putting out a stove fire are dousing with liberal amounts of water and dumping sand or dirt on the stove. If none of these is available you can also try tossing an empty pot over the stove. The hope is that lack of oxygen will put out the fire; however, the pot also concentrates the heat, which could cause a more violent ignition before the fire is extinguished.

Be careful with stove fuel and plastic pumps. Make sure that you don’t spill fuel on stoves with plastic pumps. If there is fuel on the outside of the pump while the stove is lit, it can catch fire. A fire on a plastic pump can melt the pump, allowing more fuel to flow out and ignite, a potentially explosive situation.

How Much Fuel to Bring

The amount of fuel you need depends on the size of your group and the type of items on your menu. Cooking at high altitude (see page), boiling water for purification, or melting snow for water will increase your fuel requirements. The following are guidelines for typical three-season trips cooking for breakfast and dinner:

WHITE GAS FUEL GUIDELINES

Season Fuel/Person/Day Summer 1/6 quart (157 milliliters) Spring and fall 1/4 quart (236 milliliters) Winter or at high altitude 1/2 quart (473 milliliters) if you need to melt snow for waterUSING A WHITE GAS STOVE

Operation

White gas stoves fall into two categories: those where the fuel bottle/pump is integrated with the burner and no assembly is required; and component stoves with a separate burner, pump, and fuel bottle, like the MSR Whisperlite, the Coleman Apex II, and the Primus Omni Fuel. Component stoves need to be assembled before use, and proper assembly is essential for safe stove operation.

Read the product literature that comes with your stove carefully for the latest instructions and information on how to assemble and use your stove properly. The following instructions are representative of component stoves and are based on MSR stove instructions with permission of MSR. Always follow the instructions that came with your stove, as this information may not be the most current.

Assembling the Stove

1 Fill an MSR Fuel Bottle to the marked Fill Line. Use only MSR fuel bottles. Non-MSR fuel bottles may result in fuel leakage and/or separation from the Pump. Fuel may ignite, possibly resulting in injury or death. (Make sure the bottle is not dented. Small holes can cause pressure loss or fuel leaks.)