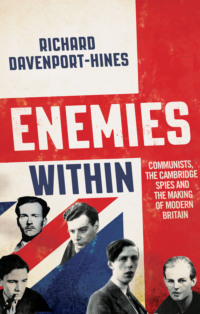

Enemies Within: Communists, the Cambridge Spies and the Making of Modern Britain

Enemies Within is not a pantechnicon containing all that can be carried from a household clearance: it is a van carrying a few hand-picked artefacts.

CHAPTER 1

The Moscow Apparatus

When Sir John (‘Jock’) Balfour went as British Minister to Moscow in 1943, he was given sound advice by the American diplomat George Kennan. ‘Although it will be very far from explaining everything,’ Kennan said, ‘it is always worthwhile, whenever the behaviour of the Soviet authorities becomes particularly difficult, to look back into Russian history for a precedent.’ Current ideas and acts, he understood, encase past history. Similarly, in 1946, Frank Roberts surveyed post-war Soviet intentions from his vantage point in Britain’s Moscow embassy. ‘Basically, the Kremlin is now pursuing a Russian national policy, which does not differ except in degree from that pursued in the past by Ivan the Terrible, Peter the Great or Catherine the Great.’ The chief difference between imperial and Stalinist Russia, according to Roberts, was that Soviet leaders covered their aims in the garb of Marxist-Leninist ideology, in which they believed with a faith as steadfast as that of the Jesuits during the Counter-Reformation.1

Although Tsar Alexander II had abolished serfdom in 1861, most of the subjects of his grandson Nicholas II lived in conditions of semi-vassalage in 1917. It was the promise of emancipation from Romanov controls, exploitation, injustice and ruinous warfare that made the Russian people give their support to the Bolsheviks. Lenin’s one-party state faced the same crisis of economic and institutional backwardness that had overwhelmed the last Tsar: industries, agriculture, bureaucracy, the armed forces and armaments all needed to be modernized, empowered and expanded at juddering speed. As Kennan and Roberts indicated, a sense of the historic continuities in Leninist and Stalinist Russia helps in evaluating Moscow’s ruling cadres and in appraising the function and extent of communist espionage. It matters as much to stress that the pitiless energy and ambition of the Bolshevik state apparatus surpassed any previous force in Russian history.2

Tsarist Russia

Russia’s earliest political police was the Oprichnina. It was mustered in 1565 by Ivan the Terrible, Grand Duke of Muscovy and first Tsar of Russia. Ivan’s enforcers dressed in black, rode black horses and had saddles embellished with a dog’s head and broom to symbolize their task of sniffing out and sweeping away treason. During the European-wide reaction after the Napoleonic wars, a new apparatus called the Third Section was formed in 1826. It was charged with monitoring political dissent and social unrest, operated in tandem with several thousand gendarmes and employed innumerable paid informers. Annual summaries of the Third Section’s surveillance reports were made to the tsarist government. ‘Public opinion’, declared the Third Section’s Count Alexander von Benckendoff, ‘is for the government what a topographical map is for an army command in time of war.’3

From the 1820s political dissidents, criminals, insubordinate soldiers, drunkards and vagabonds were deported in marching convoys to Siberia. They were consigned to this harsh exile (often after Third Section investigations) partly as condign punishment, but also to provide labour to colonize and develop the frozen wastes beyond the Ural Mountains. The rape of women, male and female prostitution, trafficked children, flogging, typhus, tuberculosis, the stench from human excrement, the hunger and destitution that occurred inside the penal colony became notorious as the number of exiles mounted (in the century before the Russian revolution of 1917, over a million individuals had been sent to Siberia).

After the fatal stabbing of the Third Section’s chief in 1878, a new state security apparatus named the Okhrana was instituted to eradicate political crime. Its draconian prerogatives were exercised with restraint in some respects: only seventeen people were executed for political crimes during the 1880s; all were assassins or implicated in murderous plots (a youth hanged for conspiring to kill Tsar Alexander III in 1887 was elder brother of Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov, who took the alias of Lenin). But Okhrana’s policemen were empowered to imprison and exile suspects in Siberia on their own authority. Thousands of deportees died there of disease, hunger and exhaustion. The overseers of one gang of convict roadbuilders starved their men into cannibalism. Exiles were regularly flogged with the cat-o’-nine-tails.

Not everyone suffered intolerably. Conditions were generally ameliorated at the time of Lenin’s exile in Siberia in 1897–1900. While living in a peasant hut surrounded by steppe, swamp and the village dung-heaps, he was able to borrow statistical, political and economics books from libraries, and published The Development of Capitalism in Russia, which established him as a Marxist ideologue. He secured a lucrative contract to translate into Russian The History of Trade Unionism by Beatrice and Sidney Webb. The authorities allowed him to keep a two-bore shotgun, cartridges and an Irish setter to hunt duck and snipe. Throughout his exile, Lenin played chess by correspondence across Russia and abroad. His letters were intercepted but seldom stopped: he maintained contacts with conspirators and subversives far away in Moscow, Kiev, Geneva and London. ‘Lenin’s letters from Siberia make strange reading,’ writes Victor Sebestyen. ‘They might be the letters of an indolent country squire of outdoor tastes but gentle epicurean philosophy which forbade him to take such tastes too seriously.’4

At 1 January 1901 there were as few as 1,800 political exiles confined in Siberia, with a few thousand more kept under police supervision, in remote provincial districts, as punishment for political crimes. About 10 per cent of those confined in Siberia in 1901 had been condemned to hard labour. Trotsky, who was exiled to a forlorn village in 1904, used his time to study Marx’s Das Kapital, to father two children and to play croquet. In the aftermath of the revolutionary uprisings of 1905 there was renewed and intensified repression. The total of those sentenced to exile rose from 6,500 in 1905 to 30,000 in 1910. The living conditions of exiles deteriorated hideously. Some sixty of the leaders of the October revolution in 1917 were, like Lenin and Trotsky, former Siberian exiles. They learnt there to be merciless and vengeful, to cherish personal enmities, to bide their time, to foster fratricidal resentments. Bolshevism was Siberian-made.5

During the 1890s anti-tsarist conspirators developed new underground networks, which no longer plotted to seize power by sudden violent blows against the authorities but sought instead to topple tsarist absolutism by organizing the oppressed workers in a mass movement that would be too populous for Okhrana repression. They adapted the methods of German social democracy for the Russian environment. Okhrana agents continued to penetrate the revolutionary movement, report on discussions and remit secret material (the young Stalin, it has been suggested, acted as an Okhrana informer and agent provocateur). The Okhrana’s foreign agency – based in the Russian embassy in Paris – kept émigrés and fugitive revolutionaries under trans-European surveillance. To counter the Okhrana’s countless paid informers, revolutionaries became expert in running clandestine groups, holding undetected meetings and evading surveillance. Bolsheviks learnt, as one example, to write secret letters, which were to be sewn into the lining of clothes, not on paper, but on linen, which did not rustle incriminatingly if a courier was searched.

The Bolsheviks’ organizational culture was conspiratorial from top and bottom. Their leaders acted under protective party disguises: Iosif Vissarionovich Dzhugashvili took the revolutionary pseudonym of Stalin because it resembled the sound of Lenin; Leon Trotsky had begun life as Lev Davidovich Bronstein; Grigory Yevseevich Zinoviev was the fighting name of Hirsch Apfelbaum alias Ovsei-Gershon Aronovich Radomyslsky; Maxim Litvinov was born Meir Henoch Mojszewicz Wallach-Finkelstein, and had the intermediate alias of Max Wallach; Vyacheslav Scriabin took the hard man’s name of Molotov, meaning ‘hammer’. Bolsheviks were indoctrinated with the need for secrecy: they grew adept in subterfuge and misdirection, and remained hyper-vigilant about enemies long after seizing power in 1917. As revolutionaries they pursued both overt and covert operations to weaken the institutions and governments of their enemies. The necessary crafts for survival in tsarist Russia, including secret cells and the transmission of secret material, were adaptable for foreign espionage.

Leninist Russia

Marx belittled the Lumpenproletariat who made mid-nineteenth-century revolutions: the urban forces that brought Louis Bonaparte to power in 1848 were, he wrote, a rabble of decayed roués, bourgeois chancers, ferret-like vagabonds, discharged soldiers, ex-prisoners, spongers, drifters, pickpockets, confidence-tricksters, pimps, literati, organ-grinders, rag-pickers and tinkers. Marx regarded universal suffrage as a fetish, Bonaparte as a reckless gambler, his election by popular vote as head of the French state as a pathological symptom, and Bonapartism as little different from tsarism. He regarded the working of economic laws as the paramount and predestined cause of revolution, and considered assertions of collective social will as subordinate factors. ‘The strength of Marxism’, wrote R. C. (‘Robin’) Zaehner, a Secret Intelligence Service (SIS) officer in Iran during the 1940s, ‘is that it is a revolutionary creed which offers an earthly paradise here and now, which claims to be scientific, and which would have us believe that the classless society is the inevitable result of the evolutionary process.’ Communism, continued Zaehner, repudiates individualism, self-regard, personal enterprise and the rights of private property: indeed considers them as condemned at the bar of historic destiny.6

The Bolshevik revolution in 1917 did not fit the principles of Das Kapital. Mechanized slaughter rather than, as Marx predicted, the breakdown of capitalism brought communist revolution to Russia. It was not the Bolshevik insurgents who made the revolutionary situation, but the European ‘total war’, which overwhelmed tsarist autocracy, brought military collapse, civilian exasperation, hunger and fatigue, and forced the abdication of Nicholas II in March 1917. The decision of the provisional government, which replaced the Romanov monarchy, to continue participation in that war led to the swift rise of several distinct mass movements: the urban proletariat (organized in ‘soviets’, viz. councils elected by manual workers), the peasantry, soldiers and sailors, non-Russian nationalities and a numerically small number of bourgeois all coalesced into different groups. The war-induced crisis discredited monarchism, liberalism and moderate socialism in turn. The collapse of state authority in 1917 had little resemblance to the military coups of politically minded soldiers, such as overthrew the Obrenović royal dynasty in Serbia in 1903 or mustered for the Young Turk revolt of 1908. Nor did it resemble the crowd pressure represented by the March on Rome led by Mussolini in 1922. It arose from the mass mobilization of peasants, soldiers and workers who were provoked by the injustice, exploitation, inequity and incompetence of their rulers, and yearned to be freed from a failed autocracy.7

On taking power the Bolsheviks sought to placate the mass movements. They signed the Brest-Litovsk peace treaty with Germany, devolved power to the soviets, redistributed confiscated lands to the peasantry and tried to vest control of factories in their workers. A giddying spiral of economic collapse, unemployment and mass privation renewed urban proletarian and peasant discontent. ‘In the course of a bitter civil war, the Bolsheviks forged a Red Army that defeated a succession of enemies, including the Socialist Revolutionaries, the Whites, Allied interventionists, and peasant partisans,’ as the historian of communism Stephen A. Smith has put it. ‘In so doing, they instituted key elements of what would become the generic communist system: a highly centralized state under a single party, the crushing of dissent, and the curtailment of popular organizations.’ Some scholars argue that this outcome was the result of Lenin’s determination to concentrate power in a single party and to eliminate political opposition. Others contend that the totalitarian state was necessitated by ‘the desperate problems the Bolshevists faced in defeating the counter-revolution, in feeding the Red Army and the urban population, in maintaining production for the war effort and in combating tendencies to crime and social anomie’. Once the Bolsheviks had trounced their adversaries, they did not revert to the decentralized socialist structures that had achieved the revolutions of 1917.8

Other preliminary points must be stressed in contextualizing the history of communist espionage in England. Nicholas II, whose Romanov dynasty had ruled since 1613, believed that he was a divine instrument, and that it was by God’s command that his subjects owed unconditional submission to his autocracy. He preferred sacred duties, mysticism and superstition to secular expertise: specialist cadres of ministers and bureaucrats were anathema to him. The Russian Orthodox Church had been a temporal instrument of the Romanov empire since the reign of Peter the Great: icons and local saints – but also devils and sprites – were vivid, active forces in the lives of the peasantry; apostasy was a criminal offence. Bolshevik Russia was the antithesis of the Tsar’s ramshackle theocracy: it was the first state in world history to be atheistic in its foundation and to deny the merit in any religion. ‘The working class has elaborated its own revolutionary morality, which began by dethroning God and all absolute standards,’ Trotsky declared in 1922. Although the Orthodox Church was one of the few Romanov institutions to survive 1917, its influence was truncated. Atheists across Europe welcomed the ruthless hostility of the pioneer socialist state to religious hocus-pocus. Kim Philby particularly but also Anthony Blunt, Guy Burgess and Donald Maclean were drawn to Marxism by its repudiation of Christianity.9

Secondly, the civil war of 1917–22 was the crucible in which the Soviet Union was forged. By one reliable computation, deaths in combat, endemic disease, disappearances and emigration led to a fall in population of 12.7 million between 1917 and 1922. During those years of savage combat the Bolshevik leadership made the communist party into a disciplined fighting force: they shed the vitiating residue of revolutionary romanticism and utopianism; they abjured clemency, lenience and individualism; and they asserted the historical inevitability of victory. Bolshevism was set on breaking the sovereignty and capitalism of nation states, installing an international workers’ dictatorship and thus accomplishing global revolution. These great aims were used to justify the exaction of huge sacrifices by the present generation for the benefit of their successors; to justify, too, forced labour and show-trials.

During the 1920s Litvinov developed a diplomatic negotiating style suitable for the dictatorship of the proletariat: exhausting, outrageous insistence on predetermined objects, regardless of truth, reason or facts. Soviet officials had neither the training nor the capacity to argue with foreign negotiators. They declared their position with immovable aggression, and never deviated from it. Molotov was true to his nom de guerre and during the 1930s and 1940s continued this hammering, defiantly mendacious manner of diplomatic exchanges. Andrei Gromyko, who in 1957 began his twenty-eight years as Minister of Foreign Affairs, was a past-master in the old Bolshevik brand of brutal diplomacy and ersatz furious indignation.

During the civil war, the Bolsheviks lost control of large parts of the Romanov empire to the anti-Bolshevist, monarchist and nationalist forces known as the White armies. At first the Ukraine, the Caucasus, the Baltic provinces and central Asia were wrested back; but by the treaty of Riga in 1921 Ukraine was partitioned between the Soviet Union and an expanded Poland. Ground was lost in Finland, the Baltic littoral, western Belorussia and Bessarabia. Soviet Russia was seen by the Bolshevik leadership as a dismembered version of imperial Russia. Russian military advances into Poland and Finland in 1939–40 show the Stalinist priority in regaining the lost territories of 1918–20. In the spring of 1945 Russia was able to reoccupy Poland, Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania, and to begin renewing its territorial and ideological control elsewhere. Britain, with its history of intervention in the civil war and as the only western European power with a major Asiatic empire, was a primary adversary, which needed to be met with espionage, subversion and ultimately sabotage.10

‘How can you make a revolution without firing squads?’ Lenin asked in 1917. ‘Do you really believe that we can be victorious without the very cruellest revolutionary terror?’ he demanded a year later. Soon he instituted so-called People’s Courts, which have been described by Victor Sebestyen as ‘essentially ad hoc mob trials in which twelve “elected” judges, most of them barely literate, would rule less on the facts of the case than with the use, in Lenin’s words, of “revolutionary justice”’. After issuing a decree in 1918 permitting the summary shooting by Red Guards of enemy agents, profiteers, marauders, hooligans and counter-revolutionary agitators, Lenin regretted that it would be impolitic to rename the Commissariat of Justice the Commissariat for Social Extermination.11

Walter Krivitsky, the first major Soviet intelligence defector, said in his MI5 debriefing of 1940 that the moment when Bolshevism swung from socialism with benevolent hopes to an entrenched tyranny occurred in 1921, with the crushing of the revolt at Kronstadt naval base. A mass meeting of sailors of the Baltic fleet demanded free parliamentary elections, the establishment of non-communist trade unions and the abolition of internal political police. Their defiance was suppressed by 20,000 Red Army soldiers whom Trotsky had promised would shoot the sailors like partridges. The quashing of the Kronstadt protest was nasty, brutish and short: reading Trotsky’s book Whither England? in 1925, the political theorist Harold Laski reflected that ‘the whole Bolshevik psychology is merely Hobbes redressed in Marxian costume’. The Hobbesian absolutist system was intended to optimize the subject’s peace and security; but, as Locke said, the tranquillity of Hobbes’s ideal commonwealth was the peace and security of a dungeon.12

Dissidents across ancien régime Europe had to contend with ‘perlustration’ (government interception and reading of mail to discover what the population is thinking and writing). The Okhrana had cabinets noirs, or ‘black chambers’, where private and diplomatic correspondence was intercepted and read, in the ten main post offices of tsarist Russia, although this involved a total staff nationwide of only forty-nine people in 1913. After the Bolsheviks had attained power in 1917, they found that a state monopoly of propaganda was the best way to monitor thoughts, control the masses and inculcate them with socialism. By 1920 they had 10,000 officials trained to read the post in Russia. They destroyed letters that criticized the regime, and quoted from representative samples when compiling summaries of mass opinion. Surveillance reports were indispensable to policing public opinion in inter-war totalitarian states, whether Bolshevik Russia, Nazi Germany or fascist Italy, and to maximizing the effects of state propaganda. Most militant Marxist revolutionaries before 1917 were ‘staunch fighters for political freedom’, as Lars Lih, the historian of Leninism, has written. ‘One of the most important political facts about the rest of the twentieth century was that the most orthodox and militant advocates of revolutionary Marxism were devoted to regimes that crushed political freedom to an unprecedented degree.’13

‘Russia is a country which it is very easy to invade, but very difficult to conquer,’ Lloyd George told parliament in 1919. ‘Starvation, bloodshed, confusion, ruin, and horror’ had been the outcome of the revolution two years earlier: he loathed ‘Bolshevik teachings’, but ‘would rather leave Russia Bolshevik until she sees her way out of it than see Britain [go] bankrupt’ as the result of military intervention against the revolutionaries. Soviet Russia nevertheless felt itself to be the target of relentless encirclement by capitalist forces and secret agents. This federation of socialist republics covered a huge area without natural defensible frontiers. Amid multitudinous evidence of London’s malign intentions, there was the agreement in 1920 between the English armaments company Vickers and its French counterpart Schneider-Creusot to develop the Polish metallurgy firm Starachowice into a munition works. Similarly, in 1921–3, Vickers invested in the privately owned naval yards at Tallinn in Estonia, becoming sole technical advisers and purchasing agents as recompense for its investment: they were, said their manager in Estonia, seeking orders for their British factories, but ‘also guided by the necessity of safeguarding as far as lay in our power the higher interests of British influence’. Both ventures proved unprofitable; but it is not surprising that the Soviets felt defensive security measures were needed.14

The Bolshevists’ first Soviet intelligence agency, named the Cheka, was formed in December 1917 with the intention of defending and extending the dictatorship of the proletariat. Much of the Cheka’s tradecraft was derived from the Okhrana, including the use of agents provocateurs to identify, incriminate and eliminate opponents. ‘Every Bolshevist should make himself a Chekist,’ Lenin once said. This was tantamount to saying that every communist must spy, steal, cheat, falsify documents, double-cross and be willing to kill. The Cheka’s emblems of a shield to defend the revolution and a sword to smite its foes were used as the insignia of its ultimate successor organization, the KGB. Until the disbandment of the KGB in the 1990s, many of its officers, including Vladimir Putin, described themselves as Chekists.15

The Cheka’s priority was arresting, shooting, imprisoning or exiling in forced labour camps Russian counter-revolutionaries, class enemies and putative conspirators whom they accused of being financed by foreign capitalism. As one of its internal documents asserted in 1918: ‘He who fights for a better future will be merciless towards his enemies. He who seeks to protect poor people will harden his heart against pity and will become cruel.’ The Chekists of the 1920s believed themselves superior to bourgeois scruples about guilt and innocence, or truth and lies. ‘Give us a man, and we’ll make a case,’ their interrogators said with pride. As Nadezhda Mandelstam testified, the pioneer generation of Chekist leaders had modish cultural pretensions. ‘The Chekists were the avant-garde of the new people and they revised, in the manner of the Superman, all human values,’ she wrote. After their liquidation in 1937, they were succeeded by a very different type of political-police enforcer.16

The tsarist Okhrana had been anti-semitic, stoked pogroms and thus drove many Jewish people into revolutionary sympathies. Under the Romanovs, Jews were barred from Russian citizenship and forbidden to print in Hebrew. Violent persecution, injustice and exclusion caused retaliatory resentment, which took political form. Many of the Chekist avant-garde were Jewish. If the fact that Lenin’s maternal grandfather was Jewish was then unknown, the identification of Kamenev, Litvinov, Radek, Trotsky and Zinoviev as Jews led to widespread European perceptions of Bolshevism as a Judaic influence. Lord D’Abernon, British Ambassador in Berlin, reflected in 1922 that Jewish small-traders in Germany felt ‘sneaking affection for the Bolsheviks. Many of them are inclined to regard their co-religionaries at Moscow as rather fine fellows, who have done something to avenge the misfortunes of the Jewish race; they consider Trotsky and the Cheka the apostolic successors to Judith and Deborah.’17