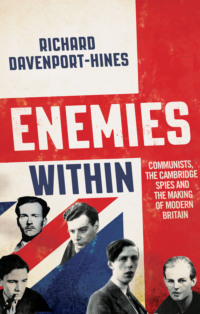

Enemies Within: Communists, the Cambridge Spies and the Making of Modern Britain

In Stalin’s toxic suspicions we reach the kernel of this book: the destruction of trust. Purges, so Nikolai Bukharin told Stalin in 1937, guaranteed the primacy of the leadership by arousing in the upper echelons of the party ‘an everlasting distrust’ of each other. Stalin went further, and said in Nikita Khrushchev’s presence in 1951, ‘I’m finished, I trust no one, not even myself.’ Soviet Russia’s ultimate triumph was to destroy reciprocal trust within the political society of its chief adversary.53

CHAPTER 2

The Intelligence Division

Every power system must defend itself against spies, traitors, rebels, saboteurs and mutineers. Cunning ambitions – both internal and external – threaten every sovereignty. Individual vanities endanger national security. Accordingly, hidden away inside the great machinery of states, there have always been the smaller apparatuses of espionage, counter-espionage and counter-subversion. Yet spies, double agents, couriers and informers are little use abroad or in the homeland, nor can the collection by licit means of foreign and domestic information be made intelligible, without offices to process material and turn it into intelligence. In England, as in Russia, the organized collection of reports and intercepts on exiles, foreign enemies and domestic rebels reached maturity in the sixteenth century.

Pre-Victorian espionage

One of the ablest men in Elizabethan England, Sir Francis Walsingham, was the country’s earliest spymaster. When in 1571 the Florentine banker Roberto di Ridolfi led an international conspiracy to kill England’s Protestant Queen Elizabeth and to crown the Catholic Queen of Scotland, Mary, in her stead, Walsingham’s organization foiled the plot, with the help of informants, torture, intercepted messages and deciphered codes. He had fifty-three agents at foreign courts, and was adept at persuading Catholics to betray one another. His apparatus detected further plots to depose Elizabeth. After the foiling of the most notable of these conspiracies, led by Anthony Babington in 1586, the Queen told her parliament, ‘Good Neighbours I have had, and I have met with bad; and in Trust I have found Treason.’1

Sectarian animosity between Catholics and Protestants, and dynastic rivalries between adherents of the Tudors, the Stuarts and the Hanoverians, involved foreign conspirators, aggrieved exiles, domestic malcontents and headstrong adventurers. European power-centres were monitored from London. The Lord Protector, Oliver Cromwell, used countless paid spies during the 1650s and was said to have ‘carried the secrets of all the Princes of Europe at his girdle’. The Venetian Ambassador in London, reporting on the Protectorate, declared that ‘no Government on earth discloses its own acts less and knows those of others more precisely than that of England’.2

During the 1720s the South Sea Company financial scandal set other precedents in the spiriting away from prosecutors of malefactors with disturbing secret knowledge. The company’s cashier, Robert Knight, after attempting to blackmail government ministers into protecting him, and reluctant to undergo close interrogation, took ship for Calais with his son and namesake. The two Robert Knights then hastened to the Austrian Netherlands, where a junior English diplomat acted on his own initiative, pursued the elder Knight with a troop of hussars and had him incarcerated, under heavy security, in the citadel of Antwerp. Although the House of Commons sought Knight’s extradition, their purpose was not punishment but political gamesmanship: the opposition wished him to divulge material incriminating office-holders. The monarch and the government were correspondingly anxious to prevent his repatriation and to silence the disruptive stories that he might tell. There followed an intricate ‘screen’: the Georgian word for a cover-up. After negotiations between London and Vienna, Knight was transferred to Luxembourg, and then taken at night to the Ardennes and set free. The authorities meanwhile arranged for a hole to be dug in the wall of the Knights’ cell, and for a rope-ladder to be lowered from it, in order to bolster the pretence that they had escaped. The determination of London office-holders that the secrets of Knight’s financial chicanery should not be publicly aired was akin to the aversion of twentieth-century authorities to sharing security failures.3

Eighteenth-century uprisings by Scottish Jacobites against the government in London were defeated by secret intelligence, disinformation and betrayals as well as by force of arms. Both sides employed messenger-spies, such as the Jacobite innkeeper who in 1745 tried to cut his throat after being captured with papers from Charles Edward, the Young Pretender, hidden in his glove. The London government gained an important advantage when the Jacobite cipher code was seized by a mob in Cumberland from the Duke of Perth’s travelling servant. After two years of imprisonment in the Tower of London, the clan chief Alastair Ruadh MacDonell of Glengarry was turned, and under the alias of Pickle acted as a secret informant on Jacobite activities after 1747. ‘Tall, athletic, with a frank and pleasing face, Pickle could never be taken for a traitor,’ wrote his biographer. ‘The man was brave, for he moved freely in France, England, and Scotland, well knowing that the sgian [small dagger] was sharpened for his throat if he were detected.’ He was not a paid informer, but a conceited man who enjoyed the secret importance of double-dealing. His second alias was Random, which suggests his liking for risk. Collectors of antiquities and works of art, who roamed Europe in pursuit of their avocation, as well as the dealers from whom they bought their rarities, had good cover for underhand activities as political agents. There were ample opportunities for gossip, covert surveillance, gambits and counter-espionage by connoisseurs who encountered Jacobites in exile. Much useless tittle-tattle from Rome or Florence about the Old and Young Pretenders was sold to London at high prices, which were paid tardily or not at all.4

The Home Office employed informers and agents provocateurs during the French revolutionary wars and their turbulent sequel. Lord Sidmouth, Home Secretary during 1812–22, became convinced by his sources, so he told the House of Lords in 1817, that ‘scarcely a cottage had escaped the perseverance of the agents of mischief’. Radicals, warned Sidmouth, ‘had parliamentary reform in their mouths, but rebellion and revolution in their hearts’. The Cato Street conspirator Arthur Thistlewood was incriminated by a bevy of police spies, including John Castle, a maker of paper dolls for children, who was also a bigamist and pimp, and George Edwards, a maker of plaster figurines, whose bestselling line was a bust of the headmaster of Eton which pupils bought to use in the manner of a coconut shy. The defence of the realm from internal foes has always needed its Pickles, Randoms and Castles.5

Mid-nineteenth-century London became a haven for political exiles (predominantly German, but some Italian). Most were quiescent refugees who sat smoking, talking, eating and drinking in Soho dives, but one account of 1859 presents a minority group of active conspirators gathering in a small Whitechapel Gasthaus known as the Tyrants’ Entrails: ‘the incandescent ones, the roaring, raging, rampaging, red-hot refugees; the amateurs in vitriol, soda-bottles full of gunpowder, and broken bottles for horses’ hoofs’. The surveillance of these irreconcilables was the preserve of foreign police spies. A Prussian spy reported in 1853 on one exile who had been born in the Rhineland, had been radicalized in Berlin and was living in two rooms in Dean Street, Soho: ‘everything is broken down, tattered and torn, with a half inch of dust over everything … manuscripts, books and newspapers, as well as children’s toys, and rags and tatters of his wife’s sewing basket, several cups with broken rims, knives, forks, lamps, an inkpot, tumblers, Dutch clay pipes, tobacco ash – in a word, everything top-turvy’. As to the paterfamilias, ‘Washing, grooming and changing his linen are things he rarely does, and he likes to get drunk. Though he is often idle for days on end, he will work day and night with tireless endurance when he has great work to do. He has no fixed times for going to sleep and waking up. He often stays up all night, and then lies down fully clothed on the sofa at midday and sleeps till evening, untroubled by the comings and goings of the world.’ It was in this squalid chaos that Karl Marx did the preliminary thinking that led to Das Kapital.6

Victorian espionage

Every successful military leader valued intelligence reports. ‘I am always preceded by a hundred spies,’ the all-conquering Frederick the Great of Prussia said in the 1750s. His decision to go to war in 1756 was based partly on the intelligence received from his spy in the Austrian embassy in Berlin, and from the interception and decoding of messages sent by the Dutch envoy in St Petersburg to The Hague. Half a century later Napoleon declared, ‘one spy in the right place is worth 20,000 men in the field’. International diplomacy also suborned well-placed informants among the desk-bound officials of other great powers. As one example, Lord Cowley, Ambassador in Vienna during the 1820s, had the private secretary of the Austrian Foreign Minister Metternich in his pay.7

An intelligence department to measure, limit and manage the risks entailed by the territorial rivalry in Asia between England and Russia was developed in London from the 1850s. This department worked with successive prime ministers and the Foreign Office to inform and strengthen imperial policy-making. William Beaver, in his pioneering study of Victorian military intelligence, argues that the Pax Britannica was intelligence-based and intelligence-led. The London government’s success during Victoria’s reign in protecting its ideals of progress, prosperity and peace was achievable only by investigating, watching and listening to hostile powers, and by collating, interpreting and acting on intelligence about potential foes. The efforts of this War Office sub-division meant that for over half a century the British Empire waged colonial wars in Asia and made localized interventions in Africa, but avoided major warfare in either Europe or Asia. ‘Britain’, says Beaver, ‘played her cards well because she sat facing the mirror.’8

This systematic intelligence-gathering was instigated by Thomas Jervis, a retired Indian Army officer of whom it was said that cartography was second only to Christianity as the ruling passion of his life. Shortly before the outbreak of the Crimean war, he bought copies of the Russian army’s secret map of the Crimea and of the Austrian staff map of Turkey-in-Europe from a source in Brussels. At his own expense he then provided the War Office with tactical maps of the seat of war. These proved invaluable at a time when British military inadequacy in the Crimea was being exposed by The Times war correspondent and by war artists whose drawings dismayed readers of illustrated magazines. The politicians sought to deflect public anger at the maladministration and tactical failures in the Crimea by incriminating the military. Sidney Herbert, the reform-minded Secretary of State for War, told the House of Commons that responsibility for the bungles ‘lies with that collection of regiments which calls itself the British Army and not with the Government!’9

Jervis campaigned for peacetime map-making, fact-gathering and tactical analysis. In 1855 he was appointed director of a new Topographical & Statistical Department (T&S) charged with supporting reconnaissance in war and intelligence-gathering in peacetime. This was reconstituted in 1873 as the Intelligence Department (ID). Although the Horse Guards generals were relentless in disliking the ID as an incipient General Staff which would reduce their prerogatives, the ID soon proved its value to the great offices of state by discounting the bellicose opinions of the military hierarchy. It provided prime ministers and foreign secretaries with evidence-based intelligence shorn of the generals’ bluster. ‘If you believe the doctors, nothing is wholesome,’ the Foreign Secretary and future Prime Minister Lord Salisbury said in 1877: ‘if you believe the theologians, nothing is innocent: if you believe the soldiers, nothing is safe.’ By the 1880s the ID was a major supplier of intelligence to the Foreign Office as well as a prototype general staff for the War Office.10

ID officers scoured the foreign daily press, and weekly and monthly periodicals, for material on foreign armies, territories and thinking. This was later known as open source intelligence (OSINT). Interesting items were indexed under four or five headings, and pasted into cuttings-books. The cellars of the nondescript ID offices at 16–18 Queen Anne’s Gate, Westminster, two minutes’ walk from the Foreign Office and Downing Street, bulged with the largest secret military library in the world. Within months of the advent of the Dewey Decimal system of cataloguing in 1876, the ID had begun cataloguing the information in its holdings to as much as seven decimal points. Its officers took pride in map-making, and established cartography as a valued precision craft. Their voracity in amassing facts, and their canny analysis of material, provided the Foreign Office, the Cabinet and ministries with product that was both hallmarked as reliable and based on innovative thinking. The ID was a paper-bound bureaucracy, in which lucid, clarifying desk-work brought promotion: Sir John Ardagh, Jervis’s ultimate successor as the ID’s mastermind, was renowned for producing ‘beautifully expressed far-seeing memoranda on the most abstruse questions’.11

The Indian Army remitted recurrent scares about Afghan uprisings and the mustering of Russian battalions. Lord Dufferin was rare among viceroys in discounting the likelihood of a Russian invasion of India: he protested in 1885 against ‘putting a frightful hole in our pocket’ by mobilizing the Indian Army ‘every time that a wretched Cossack chooses to shake his spear on the top of a sand-hill against Penjdeh’. Prime ministers learnt to trust ID reassurances about Russian intentions. Responding to an Indian Army alarm that Russia was preparing a major invasion of Afghanistan and India, the ID obtained and analysed the annual contract for procuring flour for the Russian army. It ascertained that there were no plans to build or expand flour points for bakeries on the trajectory of the planned invasion. As bakeries on lines of march to the Hindu Kush were indispensable to invasion plans, the ID advised the Foreign and India offices that without bread supplies there would be no military advance. This was a radical new way of assessing risk and laying plans.12

Politicians like to rely on instinct, which is inherently a primitive force, or on flair, ‘which means you guess what you ought to know’, as Robert Vansittart noted. The ID countered the makeshifts of instinct and flair with factually grounded intelligence assessments that gave reassurance about imperial security when rabble-rousers, apoplectic generals and press stunts seemed to presage impending Russian invasions of India. In the words of an ID paper of 1880 dispelling rumours of Russian expeditions into Afghanistan, ‘Ignorance is weakness, and this weakness we constantly show by the undignified fear displayed at every report of the threat of Russian movements.’ Just as military reverses were often attributable to poor field intelligence, so British diplomacy was sometimes outwitted by other European powers through deficient information.13

The ID attracted a new breed of ‘scientific officers’, mainly engineers and artillerymen. Unusually for the nineteenth-century army, at least a dozen had attended Oxford, Cambridge or Dublin universities; almost all were good linguists. Humour was prized: each section kept a screen on which were displayed ‘screamingly funny’ cuttings from foreign newspapers, such as an Austrian officer’s account of a Gibraltar cricket match and a Spanish scheme to train swans to tow reconnaissance balloons. The ID during the last quarter of the nineteenth century eventually produced three chiefs of the Imperial General Staff, two field marshals, six generals, eleven lieutenant generals and fifteen major generals. Over half were gazetted with knighthoods or peerages. Fewer than half ever married. Beaver identifies the ID as ‘the first real meritocratic cadre in modern British government’. As Stalin told the graduates of the Red Army Academy in a Kremlin speech of 1935, ‘cadres decide everything’.14

The ID trained men who later attained non-military but intelligence-informed positions of power: Vincent Caillard, an ID officer who served on the Montenegrin frontier commission, was rewarded with the presidency of the administrative council of the Ottoman Public Debt (1883–98), which brought him rare influence and privileged information in Constantinople. He corresponded with Salisbury on Turkish affairs, and was knighted at the age of thirty-nine. After 1906 he became central to military and naval preparedness as financial comptroller of the armaments company Vickers. In 1915–18 he was involved with the arms dealer Sir Basil Zaharoff in a fruitless scheme to bribe the Young Turks out of the war.15

After the European powers began to scramble for African territories in the 1880s, the Intelligence Division (as the Intelligence Department was renamed in 1888) became active in that continent. Its officers knew how to hold their tongues, said Ardagh, and could commit crimes while remaining gentlemanly. Theirs, he continued, were ‘the qualities disowned by the bishop who “thanked God that Providence had not endowed him with the low cunning necessary for the solution of a quadratic equation”’. All this was accomplished despite the Treasury keeping, in the words of an ID section head in the 1890s, ‘a frightfully tight hold on every sixpence’.16

‘Spies have a dangerous task, and not an honourable one; consequently, except in very rare and extreme cases, officers will not accept the invidious duty,’ wrote Captain Henry Hozier in 1867 after espionage had helped Prussia to its battle victories over Austria. Nevertheless, ‘adventurers and unscrupulous men will, if well paid, do the work, and, for the sake of a sufficient sum, run the risk of certain death’. Despite this disavowal, in the last quarter of the nineteenth century ID officers traversed the globe, ran networks in Egypt, the Sudan, the Upper Nile and the new French spheres of influence along the west coast of Africa. Always and everywhere they drew maps: cartography was an English weapon to box the French, the Germans and the Italians in Africa, the Austrians and Turks in the Balkans, and the Russians in Asia. Medals were bestowed in order to distinguish officers who were willing to reconnoitre enemy positions from those whom Hozier stigmatized as ‘mercenary wretches who will sell friend and foe alike’. Claude Dansey, the Vice Chief of SIS during the 1940s, had a soldier uncle who was awarded the Victoria Cross for his courage as a scout in the Ashanti war of 1874, and a military cousin who won the VC in 1914 for reconnaissance of enemy positions in the German West Africa protectorate.17

Clive Bigham, Lord Mersey’s young son and heir, who had distinguished himself in China during the Boxer rebellion of 1900, was recommended by the Foreign Office to Ardagh, and served in the ID until 1904. Almost his first task was to go to Paris, where he bribed newspaper editors to halt their abuse of Queen Victoria (his expenses for this task were put under the heading ‘Remounts’). Next he was posted to ID’s Section E, which covered Austria, Hungary, the Balkans and the Ottoman Empire, and commissioned to compile handbooks on Abyssinia, Morocco and Arabia. ‘These were long and interesting jobs,’ Bigham recalled, ‘for I had to sift, check, compile and arrange a mass of material; but the work attracted me and taught me a lot.’ Section E was headed first by George Forestier-Walker, who rose to the rank of major general, and then by George (‘Uncle George’) Milne, afterwards CIGS, field marshal and Lord Milne. Among Bigham’s colleagues William (‘Wully’) Robertson also became field marshal and CIGS, while Herbert (‘Lorenzo’) Lawrence became both a general and chairman of Vickers from 1926.18

In contrast to the Soviet Union’s confidence after 1917 in communism’s inevitable triumph over capitalism, the rapidly expanding British Empire showed imperialism at its most pessimistic. Bravado about national destiny and chauvinism about the British genius for world leadership were super-abundant; but they always raised countervailing voices which decried the interminable wars against the weak: Zulus, Ashanti, Benin, Afghans, Burmese and others. The colonial expansion and ‘scramble for Africa’ of the 1880s and 1890s were both vaunted and beset by misgivings. ‘Military adventure … is extremely distasteful to me,’ commented Dufferin when in 1885 he was instructed by London politicians to annex Burma. ‘The Burmese are a nice people, easily managed, and I cannot bear the thought of making war upon them.’ After the conquest of Burma, Dufferin anticipated ‘nothing but trouble and annoyance’. Sir Cecil (‘Springy’) Spring Rice, future Ambassador in Washington, wrote in 1899 after the outbreak of the South African war: ‘We are surrounded in the world by a depth and intensity of hatred which is really astonishing. If we fall we shall have a hundred fangs in our throat.’ He disliked the new bellicosity: ‘Imperialism is not so bad a thing if you pay for it in your own blood, but spending 3 per-cent out of your stock exchange gains to buy people to fight for you in picturesque places, in order to provide you with interesting illustrated papers (or new investments) is a different thing.’ On the eve of the twentieth century Spring Rice saw ‘great danger threatening’ and wished British imperialists ‘hadn’t boasted and shouted so much and spoilt our own game and turned the whole thing into a burglar’s prowl’.19

In the post-mortem after the South African war of 1899–1902, the ID was the only branch of the army to avoid censure. Scorching public anger at the humiliating defeats of British imperial forces by Boer irregulars required the Edwardian generals to submit to organizational reform: a general staff was belatedly instituted in 1904. This coincided with the reorientation of British foreign policy, which embraced its traditional enemies France and Russia as allies against its new chief adversary, Germany. The Directorate of Military Intelligence, which replaced the ID, continued the old successful methods of combining reports of British officers travelling overseas, the gleaning of OSINT from newspapers and gazettes, diplomatic and consular reports, and espionage. The Admiralty’s Naval Intelligence Division (NID) relied on similar sources, supplemented by commercial and business informants. The Foreign Office however disliked the use of military and naval attachés for espionage, fearing that they might be entrapped by counter-espionage officers and thus embarrass their embassy. Accordingly, in Berlin and other power centres, service attachés collected open material by legal methods, but shunned covert or illicit acquisition of official secrets. It was partly to keep attachés clear of spy work that new security agencies were established in 1909. It is indicative of the relative standing of military and naval intelligence that the ‘MI’ in the designations ‘MI5’ and ‘MI6’ represents Military Intelligence, not Naval Intelligence.20

The ID had further long-term influence for the good in the quality and activities of military attachés appointed to foreign embassies. They were skilled in using the well-tried ID techniques: they cultivated cordial contacts with the military officers of the countries to which they were posted; they attended manoeuvres, and watched new tactics and armoured formations; they were politically aware and kept alert to changing social and economic trends in their territories; they read newspapers and monitored specialist periodicals. Linguistic skills were a prerequisite. Noel Mason-MacFarlane, who was Military Attaché at Vienna and Budapest in 1931–5 and at Berlin in 1937–9, spoke excellent French and German and was conversant in Spanish, Hungarian and Russian. His Assistant Military Attaché in Berlin, Kenneth Strong, began intelligence work as a subaltern in Ireland in the early 1920s. During the struggle against Sinn Fein he ran informants such as railway porters, shopkeepers and barmen who would warn him of suspicious strangers in his district. He was fluent in four foreign languages and had smatterings of others. During the 1930s he was instrumental in starting the War Office’s Intelligence Corps. ‘The task of the Intelligence Officer’, Strong wrote, ‘is to exercise a spirit of positive inquiry and faculty of judgement, above all in discarding that large part of the incoming material which does not appreciably alter the known or anticipated situation, and from the residue to form a coherent and balanced picture, whether for a Supreme Commander, a Prime Minister … or for someone less elevated.’21