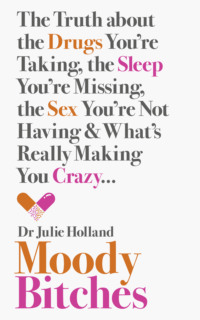

Moody Bitches: The Truth about the Drugs You’re Taking, the Sleep You’re Missing, the Sex You’re Not Having and What’s Really Making You Crazy...

All of this direct-to-consumer advertising has given many of us, especially people who came of age in the 1990s, an inflated sense that we are lay psychopharmacologists. We’ve seen enough ads to know which medicines have lower incidences of sexual side effects (bupropion, an antidepressant that does not raise serotonin levels) and which ones report an increased risk of sudden death (aripiprazole, an antipsychotic prescribed for depression, when used in elderly dementia patients). My mother often said, “A little bit of knowledge is a dangerous thing.” Gen Xers are quick to stock up on pharmaceuticals garnered from friends, the Internet, and physicians, and dole them out to friends and family. As the New York Times explained, “they choose to rely on their own research and each other’s experience in treating problems like depression . . . a medical degree, in their view, is useful but not essential.”

At this point, everybody and their cat are on antidepressants. Seriously—one of my patients has an underweight cat that was recently prescribed mirtazapine, an antidepressant that can cause increased appetite. In today’s insurance-driven health-care system, handing over a prescription is the easiest, quickest way for doctors to get someone out of their office so they can see their next patient. It also keeps the patients coming back for easy, efficient refills. Unfortunately, shorter doctors’ visits, now the norm, mean more time spent alleviating symptoms with pills and less spent digging down to really fix the problem. There is simply no talking about the harder but healthier ways to treat the symptoms. Cholesterol-lowering medicines called statins are a good example. A doctor can spend twenty minutes trying to educate a patient about dietary changes and exercise that could lower cholesterol levels, or can hand over a prescription for a pill being pushed by every drug rep who comes to the office bearing a tray of cheese Danish.

Women are particularly vulnerable to overprescribing. Numerous medical chart reviews consistently show that doctors are more likely to give women psychiatric medications than men, especially women between the ages of thirty-five and sixty-four, who often present with complaints of nervousness, difficulty sleeping, sexual dysfunction, or low energy. A patient recently asked me if he should take Risperdal, an antipsychotic, for his nervousness, because his female colleague told him it had been helping her with anxious thoughts. Risperdal was originally formulated for use in schizophrenia, but people with schizophrenia make up only 1 percent of the world’s population. It’s obviously better business to target 50 percent of the population: women.

I’m not suggesting that all use of psychiatric medicines is counterproductive. People who don’t really need these meds are taking them, while people who are genuinely psychiatrically ill remain undiagnosed and untreated, often due to socioeconomic factors. Clearly there are times when we need to pull out the big guns. Vegetative depressions that last for weeks, when you can’t get out of bed, bathe, or feed yourself, are not going to resolve themselves through soul-searching. Manic episodes where there is no sleep to be had for many days in a row will require mood stabilizers. But we’ve gotten ourselves into a situation in America now where more women are taking antidepressants and antianxiety medications for years on end, and it’s lowering the bar for all of us, creating a new normal in terms of invulnerable posturing and emotional blunting, and, more important, it is changing the tipping point for when other women will seek chemical assistance.

Cosmetic psychopharmacology is not unlike cosmetic surgery. As more women get breast implants, the rest of us feel flat chested. And so it is with more women taking antidepressants and antianxiety medications. Suddenly, you’re the odd one out if you aren’t like your friends, taking something to “take the edge off ” or give you a little lift to withstand the slings and arrows on your journey. More women are feeling lousy and finding themselves on psychiatric medications, and staying on them far longer than they were ever meant to be used. And we’re not necessarily getting any better.

Made to Be Moody

As women, our interior lives are complex and ever changing. Our neurotransmitters and our hormones—estrogen in particular—are intricately linked. When estrogen levels drop, as in PMS, postpartum, or perimenopause, it’s common for moods to plummet as well. Waxing and waning levels of estrogen help us to be more emotional, allow us to cry more easily and even to break down when we’re overwhelmed. There are estrogen receptors throughout the brain that affect our mood and behavior, and there are complex back-and-forth interactions in the brain between estrogen and serotonin, the main neurotransmitter implicated in anxiety and depression. Although it’s more complicated than I’m making it out to be, it’s helpful to think of serotonin and estrogen as yoked. When one is up, the other is likely to be as well. So it is not your imagination. Where you are in your reproductive cycle, monthly and over your lifetime, is an enormous factor in determining what you are feeling.

Think of serotonin as the “it’s all good” brain chemical. Too high and you don’t care much about anything; too low and everything seems like a problem to be fixed. When serotonin levels are lower, as is seen in PMS, emotional sensitivity is heightened. We’re less insulated and end up more cranky, irritable, and dissatisfied. The most common antidepressants, also used to treat anxiety, are serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs). These are medicines (such as fluoxetine, sertraline, paroxetine, citalopram, and escitalopram) that block the brain’s natural recycling of the serotonin back into the nerve cell, so more can get across to the next neuron. If your serotonin levels are constantly, artificially high, you’re at risk of losing the emotional sensitivity that makes you you. You may be less likely to cry in the office or bite your nails to the quick, but you’re also going to have a harder time reacting emotionally and connecting fully with others, especially sexually.

SSRIs not only affect behavior, they alter perception of the environment. If the “it’s all good” chemical is bathing your brain, will you really try very hard to fix anything? At higher doses, SSRIs sometimes promote apathy and indifference. Patients report having less motivation overall. When one of my patients becomes blasé about things, making the big W sign for “whatever” about life, it’s a sign to me that she might be overmedicated, and it’s time to taper down the happy pills. Being more complacent and apathetic can have disastrous effects on your life, both at home and at work.

Sometimes, if I see a patient with crippling depression or anxiety, then prescribing an SSRI is the right call, but even if it is the best initial treatment, it might not be the forever cure. Feeling deeply may, at times, be difficult to navigate, but it’s also a powerful tool, in the workplace and at home, and it’s essential for growth. We are built to be highly attuned and reactive, and embracing that truth is the first step in gaining mastery of our inner lives and our health.

Hardwired to Feel

Women’s brains develop differently from men’s, and the distinctions make for profound differences in how we process and communicate emotions. All brains develop along the same pathway in the womb, but things change for boys at eight weeks, once the testes become functional. With testosterone in the mix, a surge in the male sex hormone kills off many cells in the communication centers and grows more neurons slated for action, aggression, and sexual drive. In men, these brain areas take up two and a half times the space they do in women.

Even more brain changes occur after gestation, during adolescence, when sex hormones surge, further differentiating the sexes. As the female brain develops, more space and more brain cells are reserved for language, hearing, and memory. Our memory center, the hippocampus, is larger than men’s, perhaps reflecting an evolutionary advantage of remembering details of emotional events and the crucial behaviors of our potential mates, especially what they said they’d do versus what actually happened. Our memories have an influence on our emotions. The hippocampus can calm the hair-trigger responses of the amygdala, the area of the brain devoted to fear, aggression, and anger. The amygdalae are larger in men and have receptors for testosterone.

Ever wonder why you can lose it and then calm down, but those feelings continue to echo for your husband? Women’s larger hippocampi and smaller amygdalae may add up to our having better control over our emotional outbursts than men, particularly when it comes to actions involving fear or aggression. We might react emotionally, but then we pull it together, thanks to the hippocampus.

We are not living in a world that is kind to this sort of behavioral response, though. When under acute stress, the amygdala gains in functionality and the hippocampus loses, one reason you panic and can’t remember as well when pushed. The biggest problems come with chronic stress, where the hippocampus loses not just functionality but brain cells. It becomes atrophied, can no longer quiet the raging amygdala, and then all responses to stressors are amplified. This is what is seen in posttraumatic stress disorder, and it may well be seen in anyone undergoing chronic stress.

Intuiting the motives and feelings of others is an essential social skill that is employed unconsciously and automatically and has been characterized as quintessentially feminine. The better we are at sensing our body’s signs of arousal (feeling our own heartbeat, for example), the better we are at judging emotions in ourselves and others. The insula, thought to be the seat of self-awareness, empathy, and interpersonal experience, helps us to understand others and is noticeably bigger in women. The insula not only helps us process “gut feelings,” to figure out what we and others are feeling emotionally, but also enables us to experience and recognize body sensations. What has often been labeled “female intuition” has served women well in their traditional roles as caregivers and nurturers. The ability to intuit the emotions and desires of others has helped women better predict whether a man may become violent or abandon the children, or whether our nonverbal babies are hungry or in pain.

Men aren’t built to be as sensitive as women are. Women have more brain circuitry not only for expressing language and emotion but also for detecting emotional nuance and anticipating what others are feeling. Given that there is such a gender discrepancy with this empathic system, it’s likely not your imagination that your boyfriend has no idea what he’s feeling half the time (called alexithymia) and has even less facility at communicating it. Testosterone impairs empathy and the ability to intuit others’ emotions by reading their eyes. Being aware of or oblivious to others’ needs is bound to affect how giving a person is, one reason you might think of him as selfish.

We register conflict more deeply than men, and get more stressed out about it as well. No doubt some of this is learned behavior, as girls are often encouraged to keep the peace more than boys, but there is a strong biological component. When men are threatened, their bodies go into “fight or flight” mode, with adrenaline surging to provide energy to muscles. When stress levels are high in women, “tend and befriend” behavior often predominates. Women are more likely to band together in the face of adversity, creating strength in numbers, huddling together to save the children and one another. Oxytocin, the hormone released in women after orgasm and during cuddling or nursing, encourages prosocial, trusting behavior, while testosterone tends to fuel aggressive, competitive behavior. In both men and women, high testosterone levels blunt oxytocin levels, and vice versa, so there is give-and-take between aggression and bonding. Oxytocin’s release affects women more powerfully than men, helping us to be more generous and connected. It also helps us to figure out who is in and who is out of our circle of contacts, our tribe. In hostile environments, or with unsupportive contacts, oxytocin may actually enhance the stress responses, even playing out as aggression toward strangers. Protective mothers’ maternal aggression has been linked to oxytocin, for example.

Girls flock together and keep social harmony, often through language. Staying connected via gossip and verbal intimacy leads to a rush of dopamine, one of the brain’s pleasure chemicals, and oxytocin. Estrogen triggers dopamine and oxytocin production in pubescent girls. Midcycle, these hormones peak, as do verbal output and desire for intimacy. Whereas women tend to discuss troublesome issues with peers, men tend to process their troubles alone, nonverbally. This may reflect the balance of oxytocin versus testosterone. Testosterone inhibits talking and the drive to socialize. For boys, self-esteem comes from being independent, not interconnected. Boys aren’t as communicative, and they aren’t nearly as derailed by conflict and competition. It’s part of who they are, and, perhaps equally important, who they’re expected to be.

The connections between the areas of the brain that process emotion are more active and extensive in women. Women have nine areas devoted to this function, compared with only two in men. Women also have more bilateral processing of emotions in their brains, going left to right, right to left, connecting the analytic and emotional areas, whereas men tend to stay more within each hemisphere. So we could say that women are using their whole brains while men are often using only half of theirs at a time. Women do seem to be better at multitasking than men. Men not only have more difficulty juggling multiple priorities but they are also slower and less organized than women when switching between them.

Men’s brains have more linkages with their cerebellum, the control center for movement, so for men, there may be less time between seeing and doing than there is for women. Men tend to outperform women on motor and spatial cognitive tasks, while women are faster in tasks of emotional identification and nonverbal reasoning. We also outperform men on a “lost key” challenge; maybe this is why our families ask us where everything is, and, more important, why we know the answer. Because men were primarily the hunters and we the foragers, it was crucial that we remembered where we last found the good food.

Obviously, we must be cautious in discussing differences between the sexes because there is a large variation within each gender, and nurture and culture factor in nearly as much as nature does. There is interplay between our natural abilities and how we are molded to behave that is impossible to fully tease apart. Case studies of children with ambiguous genitalia who are raised to be male or female even though they possess the opposite genetic material are rare, but they do help to teach us one thing: the influence of biology cannot be underestimated. Often, our own balance of testosterone and estrogen levels dictates how aggressive we’ll be in a pickup game of basketball (or if we’d ever be caught dead in a pickup game of basketball) more than anything our parents ever taught us.

The Downside to Feeling Deeply

While biology may provide women with a set of attributes, from brain structures to hormones, that are advantageous in our traditional roles of nurturing and caregiving, there is a downside. These same attributes may also make us more inclined to suffer from depression and anxiety. In childhood, no difference exists in the prevalence of depressive disorders between girls and boys. In adulthood, women are twice as likely as men to experience depression and two to four times more likely to be diagnosed with an anxiety disorder like panic attacks or generalized anxiety.

The increased risk begins early in adolescence as puberty strikes. It ends by age sixty, when hormonal cycling ceases. Although some of the increased incidence of depression in women may result from societal factors like body image pressures, or their greater tendency to seek help for mental health issues, or diagnostic bias among doctors, there is strong evidence that much of the gender difference in mood disorders is linked to hormones.

Some women are more susceptible to hormonal fluctuations than others. There is a subgroup of women who seem to be at risk for what’s called reproductive depression, that is, mood changes caused by variations in hormone levels, like those seen prior to menstruation or after delivery. If you’re the PMS type, you’re also more likely to have postpartum depression or perimenopausal mood instability. Certain women have a specific sensitivity to these hormonal changes while some lucky ones don’t, possibly dictated by genes governed by changing estrogen levels. The good news is, when your hormones aren’t fluctuating, like when you’re postmenopausal, the risk for depression isn’t elevated. After menopause, the risks even out, especially two years after the final menstrual period, when the dust has settled. There is truth to the idea that the years after menopause are a real prime time of life for many women, both professionally and personally.

Again, there are likely evolutionary reasons for mood variability being tied to hormonal fluctuations. There is a positive mood state (called euthymia) in the first half of the menstrual cycle, leading up to ovulation, that encourages a woman to connect with mates and conceive. The more depressed, progesterone-heavy state in the second half of the cycle helps to ensure the safety of the product of conception by keeping the woman passive, cautious, and out of danger. Progesterone rises during the second half of the menstrual cycle and surges even higher if an egg is fertilized. It is the main hormone that maintains pregnancy. Progesterone is implicated in premenstrual syndrome, postpartum depression, and dysthymia, a chronic low-grade depression. The increased incidences of depression and anxiety during pregnancy (particularly in the first trimester) and the immediate postpartum period come during crucial periods for the baby, when more cautious and isolative maternal behavior can help ensure the baby’s survival. If women develop these behaviors, whether conserving precious energy or avoiding dangerous situations, then these traits will be passed on. Viva Darwin.

Anxious and depressed behaviors have survived in our gene pool for millennia because they are adaptive. They confer an advantage to our survival and that of our offspring. An anxious, obsessive forager will not only find more food, but will also return home safely. She is also more likely to keep her children out of harm’s way. Likewise, a depressed woman will more quickly withdraw from wasted enterprises, whether pursuing food or a mate, and conserve her energy. This may be the basis for seasonal affective disorder, which causes lower energy and motivation when food supplies are most scarce.

When women feel under threat, estrogen helps us to “maintain,” to be resilient and bounce back. In this way, estrogen is really acting as a stress hormone. One of the ways estrogen builds resilience is by enhancing serotonin levels, which help to keep us fortified, calmer, more rational, and less emotional. Serotonin activity is greater during higher estrogen levels. When estrogen surges, it causes more serotonin to be made, and it also causes serotonin receptors to be made. But, as with most things in the body, what goes up must come down. The natural process of stress triggering surging estrogen levels has a built-in stop mechanism, which then normalizes our serotonin levels.

SSRIs are the most common treatment for depression and anxiety, but if you’re on SSRIs, with steady serotonin levels, you miss out on this natural ebb and flow of serotonin in response to estrogen. You stay more rational and less emotional. Estrogen fluctuations help to keep us sensitive. SSRIs deaden our sensitivities.

More women than men get depressed, and estrogen may have a lot to do with this. Estrogen affects how serotonin functions in the brain. Women are more vulnerable to changes in serotonin levels and more responsive to drugs and medicines that affect serotonin. This is one reason that women may be more affected by sexual side effects of SSRIs than men. So where you are in your menstrual cycle or your perimenopausal staging will have effects on your mood, like how irritable, sensitive, or impulsive you are, as these behaviors are affected by serotonin. As you’ll see in the next chapter, it’s normal to have times in your cycle when your estrogen is lower, which means your serotonin will follow suit and you’ll feel lousy. It’s temporary and it’s natural. You don’t necessarily need daily antidepressants to mask these moods.

SSRIs can do many wonderful things for people with serious depression, and I have to admit that my patients love the way they make them feel, at least at first, but they can also take many sensations away. SSRIs tend to blunt negative feelings more than they boost the positive ones. On SSRIs, you probably won’t be skipping around gaily with a grin plastered on your face; it’s just that you’re less likely to feel tearful, irritable, and hopeless. People on SSRIs report less of many other human traits: an ability to cry, irritation, care about others’ feelings, sadness, erotic dreaming, creativity, surprise, anger, expression of their feelings, and worry.

One of my best friends from college told me a story of when she was first prescribed fluoxetine. “It really scaled back my empathy. Since I was a young girl, I’ve always felt bad if someone else felt bad. It’s a big part of who I am. I would let the other kids find the Easter eggs during the hunt, because they seemed to want them more than I did. When I first went on fluoxetine, I remember seeing another woman crying and thinking, Looks like you have a personal problem. Sucks to be you. This is what it must feel like to be a dude.” SSRIs affect emotional processing and turn down the empathy response. This can have devastating effects on the ability to parent or to maintain relationships.

It’s All Right to Cry and Get Angry

Antidepressants can be utilized as a starting point for benefiting from psychotherapy or creating lifestyle changes, but once those behaviors are firmly in place, the medications often can and should be tapered off. If you break your leg, you don’t keep the cast and crutches forever. Before you commit to a lifelong SSRI prescription, consider the dynamic emotional range you might be giving up.

My patients on SSRIs will report, “I knew the situation was upsetting. I was supposed to be feeling sad, but I couldn’t cry.” Crying isn’t just about sadness. When we are frustrated, when we are angry, when we see injustice, when we are deeply touched by the poignancy of humanity, we cry. And some women cry more easily than others. It’s normal. It’s how we’re designed, and it doesn’t mean we’re weak or out of control.

Crying allows us to deeply feel what we’re feeling and then move on. It is a crescendo that naturally leads to a denouement of intensity. For most women, this depth of feeling is a birthright, but if you really can’t stand crying, or get frustrated because you can’t speak when your throat tightens, here are two tricks that work well instead of meds. Simply think up lists of rhyming words, or subtract sevens from one hundred. Shunting blood away from the emotional centers and over to the rational verbal or calculating areas will mollify most people. (You just have to remember to do it, which means relying on your hippocampus to tamp down your amygdala.)

There are times when it’s inconvenient, to say the least, to cry, but there are other times when it’s to your advantage. Letting yourself cry can be important in communicating with your partner. A clear, visible sign that we’re upset may be just what men need. Women pick up subtle signs of sadness in others 90 percent of the time. Men are better able to discern anger and aggression; when trying to decide whether their female partner is sad, men are right only 40 percent of the time. That’s less than if they flipped a coin to help them answer. This is also a reason to express your feelings verbally and not expect your male partner to know how you’re feeling by how you look or act. They’re simply not constructed for intuiting emotion the way we are. As for families, sometimes it’s a good idea to let your kids see you cry, especially if they’ve scared you with reckless behavior or frustrated you with thoughtlessness. Tears can underscore lessons in how their behavior affects others.