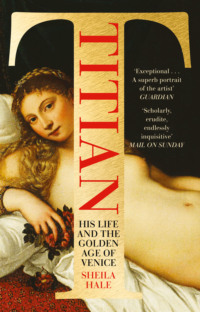

Titian: His Life and the Golden Age of Venice

he is extremely modest; he never assesses any painter critically, and willingly discusses in respectful terms anyone who has merit. And then again he is a very fine conversationalist, with powers of intellect and judgement that are quite perfect in all contingencies, and a pleasant and gentle nature. He is affable and copiously endowed with an extreme courtesy of behaviour. And the man who talks to him once is bound to fall in love with him for ever and always.

But elsewhere Dolce uses the verb giostrare, to joust, to indicate a competitive streak. Vasari, who as a Tuscan had reservations about the Venetian way of painting, described him as ‘courteous, with very good manners and the most pleasant personality and behaviour’, an artist who had surpassed his rivals ‘thanks both to the quality of his art and to his ability to get on with gentlemen and make himself agreeable to them’. An anonymous biographer writing in the seventeenth century described him as of a pleasing appearance, circumspect and sagacious in business, with an uncorrupted faith in God, loyal to the Most Serene Republic (a courtesy title given to other European states but most often to Venice, which was widely known as La Serenissima in its strongest period) and especially to his homeland of Cadore. He is candid, open-hearted, generous and an excellent conversationalist. ‘Titian’, wrote his other posthumous biographer Carlo Ridolfi, echoing Vasari, ‘had courtly manners … by frequenting the courts, he learned every courtly habit … People used to say that the talent he possessed was a particular gift from Heaven, but he never exulted in it.’ Yet Ridolfi gives us a hint of rough edges to the polished surface of his subject’s character. Titian, he tells us, was dismissive of lesser talents, and the highest praise he could bestow on a painting he admired was that it seemed to be by his own hand. What none of his early biographers mention is the lifelong loyalty and devotion to friends and family, the capacity for enjoying himself in company or the dry sense of humour, which must have been one of the qualities that made him such agreeable company. None of them – perhaps because they were all, apart from Vasari, themselves Venetians – says how typically Venetian he was: good humoured, thrifty to the point of stinginess, sweet-tempered but manipulative when necessary for his own ends, and very much his own man.

If you spend a day or two in Cadore you will see Titian’s features again: the long bony face, the slightly hooked nose, the fierce gaze. Natives of Cadore are the first to tell you that they look like Titian, and a surprising number bear the name Vecellio – there is a trend in small isolated communities for surnames carried on the male line to increase over centuries. By the time Titian was born, the Vecellio were already one of the largest and most distinguished old families in Cadore. Vasari described the family as ‘one of the most noble’, a word that was used in the annals of the Vecellio, although no member of the family was of the patrician class and none before Titian himself actually received an imperial title. But his upbringing as a member of a prominent family proud of its long lineage and history of public service might go some way towards explaining the social confidence and the ease with which he acquired those pleasing manners, which were unusual if not unique for an artist at that time.

The Vecellio of Cadore can be traced back to the second half of the thirteenth century. Most were notaries who occupied important positions in the local government. To qualify as a notary it was necessary to be nominated by a count palatine, a man given that title by the emperor, then to satisfy the local authorities, many of whom were also notaries, of competence by delivering before them an eloquent dissertation in Latin in the style of the great Roman advocate Cicero. Notaries were therefore by definition reasonably well connected and educated men. In remote communities like Cadore they fulfilled the roles of attorney, accountant and broker. Their signatures on wills, inventories, powers of attorney, dowry agreements and sales of property gave such documents, theoretically at least, international validity. One of them, a certain Bartolomeo, was also a timber merchant who owned sawmills at Perarolo that Titian would later inherit. Titian’s grandfather, known as Conte and one of the most remarkable of the Vecellio clan, must have made a strong impression on the young Titian. He was a shrewd businessman who knew how to manipulate the price of imported grain and a forceful diplomat who on one occasion managed to persuade the Venetian government to lift from Cadore a punitive tax imposed on outlying regions to finance a war against the Turks. From 1458 until his death around 1513 at what must have been a very advanced age he served the local administration as court auditor nineteen times, and often as delegate to Venice. As well as these and other high public and military offices he led the local militia in skirmishes on the north-east borders of the Venetian Republic, as captain against the Turks and as commander in chief in a war between Venice and Austria.

Conte owned a group of properties in Piazza Arsenale, including the house where Titian was born, which he either gave or loaned to Titian’s father Gregorio. Although one of Conte’s least successful sons,9 Gregorio seems to have been a nice man whose ‘goodness of soul did not yield to a sublime intellect’, as a relative put it long after his death.10 Unlike most of the family he did not qualify as a notary, and his municipal jobs – overseer of the corn stores, councillor, superintendent of the castle repairs, inspector of mines (the latter appointment given him by the doge of Venice as a favour to Titian) – were honourable but minor positions. But as captain of the militia of Pieve he fought bravely in the Battle of Cadore in 1508, and it was as a soldier in armour that Titian painted his portrait (Milan, Ambrosiana) shortly before his death. Virtually nothing is known about Titian’s mother Lucia, aptly named, according to an oration given long after her death by a Vecellio relative, because as the mother of Titian and his brother Francesco she cast a radiant light (luce) on herself and her homeland. It has been suggested, without the slightest documentary foundation, that she was a servant from Cortina d’Ampezzo, and the model for the old egg-seller who sits on the steps in Titian’s Presentation of the Virgin and/or for the Old Woman attributed to Giorgione (both Venice, Accademia).

Conte’s generosity extended to his grandchildren. He provided Dorotea with a handsome dowry on her marriage to Matteo Soldani, a notary, in 1508. We know the details of Dorotea’s marriage settlement from a rare document that survives from 1539, by which time Dorotea was widowed and there was a claim against the estate of her late husband. Two-thirds of the value of dowries were by law required to be returned to wives after the death of their husbands. But the notarized evaluation of Dorotea’s dowry had been lost during one of Maximilian’s invasions. Titian, fearing that without evidence of its value, on which his sister depended for her living, it might be considered part of the contested estate, arranged for three witnesses who had been present on the day of Dorotea’s marriage to testify before a notary. The document opens a precious window on the domestic life of the Vecellio. The witnesses agreed that the dowry was worth between 700 and 800 lire. One of them, who identified himself as a nephew of Vendramin Soldani, a parish priest and archdeacon with whom Matteo Soldani had been living before his marriage, visited Conte’s house on the day of the wedding. He described the scene.

I saw many moveable furnishings, a bed, blankets, many sheets, clothing of all sorts as well as other requirements of a woman, which seemed to me a very fine dowry.

Later that evening I asked my uncle what he thought it was worth. He replied that it was certainly a beautiful dowry, worth more than 700 lire, more than you would have thought … I’m sure there was a notary taking notes, but I don’t remember who he was. When I saw the things being evaluated there were only the two old men present, that is the priest messer Vendramin and ser Conte, as well as the notary whose name I don’t recall. It’s true that I also saw ser Gregorio, the son of ser Conte and father of the bride, who was walking back and forth, up and down, but he never stood still.11

Gregorio was evidently restless, as any father might be on his daughter’s wedding day. But the fact that it was Conte who was presiding over the evaluation of the dowry is one of the clues that suggest that he was the head of the family. Was he, as Titian would be, an overbearing father capable of crushing the spirits of his weaker sons?

Two of Titian’s biographers12 tell us that he was educated under his father’s roof. Ridolfi wrote that he attended a local school for well-born boys, in which case he didn’t profit much from it because Ridolfi also said that Titian ‘was not well versed in literature’. Titian’s sister Dorotea was illiterate, and so in all likelihood were Orsa and their mother. Judging from his few extant autograph letters and from other documents written in his hand Titian was not more than adequately literate, about average for an artist at that time. A nineteenth-century scholar, after examining one of Titian’s receipts for payment, commented that the grammar and syntax of the artist who handled a paintbrush like a god was more like that of a man who was less than a boy.13 Nevertheless, although most of his mature correspondence would be composed and penned by friends and secretaries, he was more than literate and numerate enough to manage his own and his family’s business affairs with dedication and acumen. And his handwriting, although he rarely used it, was confident, steady and legible.

Although everyone heard the mass in Latin, it was not formally taught to boys under the age of ten or twelve, the age at which Titian, like most artists, began his apprenticeship. Later in life Titian picked up a smattering of what Ben Jonson, referring to Shakespeare’s lack of formal education, called ‘small Latin and less Greek’. He gave his sons the classical names Pomponio and Orazio, and in the 1530s favoured the Latin spelling Titianus for his signatures – everyone from popes, princes and noblemen down to town councillors and soldiers liked to see their names in Latin. But the assertion, usually made by scholars who have themselves enjoyed a classical education, that Titian must have read the original texts of the Latin or Greek stories he immortalized in paint fails to take account of the way artists actually worked. No Renaissance artist, with the exception of Andrea Mantegna, was able to read or write Latin. Leonardo da Vinci (who also came from a family of provincial notaries) tried to learn Latin as an adult but without success, as did Isabella d’Este, who was one of the great Renaissance patrons of artists and a collector of classical manuscripts. Mythological imagery was disseminated not by texts but by artists inspired by the antique sculptures that were being unearthed from Italian soil, and from the translations of classical texts that were increasingly available in print from the late fifteenth century. When Dolce dedicated to Titian a volume of classical texts he had translated into Italian, he wrote in the preface that he had done so because Titian would not have been able to understand the originals.14

Titian’s earliest visual education was limited to the art he saw in the churches and public buildings of Cadore: fourteenth- and fifteenth-century frescos and crude Alpine altarpieces by the German artist Hans Klocker – there were two paintings by Klocker in the parish church of Pieve – and by Gian Francesco da Tolmezzo. Antonio Rosso, whose few surviving paintings15 look like uncertain attempts to combine fifteenth-century northern European and Venetian influences, was born around 1440 in Tai, a village only a few kilometres from Pieve. He painted altarpieces in and around Pieve, where a street is named after him today. Scholars in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries liked to imagine that it must have been Rosso who spotted and nurtured the young Titian’s talent. If so, there is nothing in what little we know about Rosso’s style that looks like Titian’s early paintings.

How then did it come about that a half-educated boy from an isolated mountain community, born into a family of notaries, soldiers and public servants with no time or inclination, as far as we know, for artistic pursuits, was sent to Venice to study painting? Within fifty years of Titian’s death an answer to this question was provided by the anonymous biographer who had evidently visited Cadore and may have been repeating a family tradition: the boy had astounded everyone by painting an image of the Madonna on a wall using as his colours the nectar of flowers. The tale of the untutored child artist who demonstrates God-given skill has roots that go back at least as far as classical antiquity. The most famous example is Vasari’s account of Cimabue’s discovery of Giotto drawing sheep on a rock. Vasari applied the same story to the childhoods of Pordenone, Beccafumi, Andrea Sansovino and Andrea del Castagno. Ridolfi credited Giorgione and Tintoretto as well as Titian with the same precocity. The legend was later applied to Poussin, Zurbarán, Goya and the self-trained eighteenth-century Japanese artist Okyo Maruyama.16 The story about Titian was later taken seriously enough for some earnest believers to imagine that a damaged fresco, painted some time in the sixteenth century on the wall of a villa behind Titian’s family cottage, might have been his very first essay.

Like all persistently recurring fables the one about artistic genius as a birthright works on a number of levels. It fills vacuums in our knowledge. It satisfies a psychological need to believe that the achievements of remarkable men and women are predetermined, whether by divine right, fate or genetic predisposition. The legend of Titian’s precocious Madonna is persuasive because children, after all, do draw on walls. A child deprived of coloured pencils or paints might well try to squeeze colour from flowers. Genius, even at a very early age, often has an urgent need to express itself, and Titian may well have shown enough talent for his family to make the unusual decision to send him to Venice, as the anonymous biographer tells us, ‘so that he could learn from some skilled master the true principles and bring to perfection the disposition he had demonstrated to practise the noble calling [of painting]’.

Titian set off for Venice shortly before the end of the fifteenth century, possibly with Francesco or joined by him soon after. The journey – now a matter of two hours at most by road or railway, both of which span the deepest valleys – took several days. Although the route was well travelled the beaten tracks were often churned up by heavy rain or the gun carriages of armies. Titian’s contemporaries – not least the peripatetic Erasmus of Rotterdam, ‘citizen of the world … stranger to all’ – sometimes groaned about the discomforts of travelling anywhere in Europe at a time when the choice was between riding a horse or mule or having one’s bones shaken in a carriage with no springs for long distances over uneven ground.

Nevertheless, the journey to and from Cadore was one Titian would make over and over again throughout his life. He was not the only great Renaissance artist to emerge from a remote rural background, but no others remained as attached to their homeland as Titian. Cadore and his extended family remained the two constants of his personal life. Il Cadorino, as he is still often called in Italy, would sign paintings, letters and receipts for payments ‘Titianus di Cador’ or ‘Titianus Cadorinus’. He would marry a girl from Perarolo, where the family timber business had started. When, in the 1520s, he repainted the landscape of Giovanni Bellini’s Feast of the Gods he ‘signed’ it with an escarpment that looms over the composition just as the castle hill of Pieve dominated his native town.

He never really identified as much with Venice and rarely set his paintings in the city apart from a now lost history painting for the doge’s palace. But two haunting views of the distant skyline survive. In the first, completed in 1520 for a merchant in Ancona and often known as the Gozzi altarpiece (Ancona, Museo Civico), Venice is silhouetted at sunset against a gilded sky from which the Ascending Virgin looks tenderly down on her specially favoured city. Three years later he painted the fresco that still survives in the doge’s palace of the gigantic figure of St Christopher, patron saint of travellers, who wades through the lagoon with the Christ child on his shoulders, towering over a ghostly view of the bell tower and domes of San Marco and the doge’s palace with the craggy mountains of Titian’s homeland in the far distance.

Even in the most demanding times when he was behind with fulfilling important commissions, he escaped to Cadore for a holiday or on family business. The house in Venice on the north-east lagoon where he lived the last forty-five years of his life commanded a view of his mountains and was always full of members of his extended family. He adapted one of the greatest and best known of his last paintings, the autobiographical Pietà (Venice, Accademia), to fit the high altar of the parish church of Pieve,17 where the chapel dedicated to his patron saint, San Tiziano, had been financed by his great-great-grandfather, and where he would have been buried had circumstances at the time of his death been different. Titian would so often repeat the journey he first made as a boy of ten or twelve that he could relive it with eyes closed, recalling every twist and turn of the road, every valley and vista of the Venetian plain to the south and the mountains of his homeland to the north rinsed in the azurite distance, every farmhouse, copse of trees, cluster of wild flowers. A nineteenth-century traveller in what he called ‘Titian’s Country’18 counted 400 different species of indigenous flora in his paintings. Scholars today are at loggerheads about whether or not Titian stopped to sketch as he travelled. If so, very few of his undisputed drawings survive.

He travelled down the Piave Valley to Perarolo, the last place before Venice where you can see majestic Antelao and the two peaks of the Pelmo, the other presiding mountain of his Dolomites, which they call the Throne of God or the Doge’s Hat. The locals say the mountains turn red at sunrise and sunset and blue – as Titian painted them – after a storm. Through the pass at Longarone, so narrow that it could not be negotiated by carts or carriages; then a few miles east to the lakes and the gorge that leads to the gentle Cenedese Hills, the ‘footstool of the Alps’,19 where the less hospitable Dolomites finally give way to the soft, lush landscape of the Venetian lowlands. It was here that the boy Titian had his first sight of the Venetian plain with the Euganean Hills above Padua to the west and the Piave, now in the far distance, snaking its way towards the lagoon. The party would have stopped to feed and water the animals and spend their last night at Serravalle, then a staging post for travellers and merchant convoys on their way to and from Venice, now united with its neighbouring town Ceneda and renamed Vittorio Veneto. Many years later Titian would become attached to this area by numerous family links. He would build himself a holiday villa in the Cenedese Hills, paint an altarpiece in the church of Serravalle and marry a daughter to a gentleman farmer whose handsome house still stands there. Then on down to the lagoon by way of Conegliano and Treviso, birthplace of the first painter who would take him as an apprentice in Venice, through fields planted with vines, mulberries and Indian corn, past jutting rocks, wooded glades, flashing streams, grazing sheep, castellated farm buildings and the bell towers of small parish churches sounding the hours.

Titian mastered the art of painting landscapes early in his career, before he was entirely confident with the human figures he placed in them. But his landscapes are not so much literal views as accumulations of the features and contours of the countryside he knew so well; they record the pleasure of seeing a landscape modelled by light and shadow.20 Stimulated by Flemish and German examples,21 by his first Venetian rival Giorgione of Castelfranco, by the pastoral literature being published in Venice when he was still an apprentice, and perhaps by Leonardo, whose notes are full of discussions about landscape painting, he conjured out of the Cenedese Hills an Arcadia inhabited by Madonnas and saints, lovers and pagan deities, where fleeting shafts of golden light on green meadows, shadows cast by passing clouds and trees tossing in the wind act like choruses, setting the mood and enhancing the drama. Titian’s brush describes the weather, forecasting how it will change as the day goes on and his models, sumptuously dressed in silks and satins, the ultramarine of the Madonna’s cloaks echoed by azure mountains and skies, have moved on to another place.

In the Holy Family with a Shepherd (London, National Gallery), and more obviously in the later Three Ages of Man (Edinburgh, National Gallery of Scotland), the sun rises above the plain where the Piave winds downstream towards the lagoon in the far distance. In remoter parts of the Veneto there are still clusters of homely farm buildings very like those Titian liked to incorporate in his landscapes, often reusing the same group of buildings for different paintings. Those in the background of Tobias and the Angel Raphael are the same as the buildings in the Baptism of Christ (Rome, Pinacoteca Capitolina) and similar to those in his woodcuts of the Triumph of Christ and Submersion of Pharaoh’s Army in the Red Sea. The buildings in the Sleeping Nude in a Landscape (Dresden, Gemäldegalerie) reappear in the Noli me tangere (London, National Gallery) which Titian set on a plateau overlooking the plain. The two landscapes in Sacred and Profane Love (Rome, Galleria Borghese) evoke the same place in the golden light of sunset with the same buildings in reverse order, looking north, back towards the lakes and Alpine foothills above Serravalle and Ceneda.22

Titian’s landscapes inspired a succession of artists from Poussin and Rubens to Constable and Turner, as well as writers trying to explain or capture their magic in words. Constable, who sometimes improved his compositions by borrowing Titian’s trees, saw ‘the representative of nature’ in every touch of his landscapes. The Milanese painter and writer Giovanni Paolo Lomazzo wrote that Titian, so loved by the world, was hated by jealous nature.23 Ridolfi began his biography of Titian with praise for his ‘conquest’ of nature,

who had before considered herself insuperable, was now conquered and gave in to this man, receiving laws from his industrious brush, with the appearance of new forms in his work that rendered the flowers more beautiful, the meadows more brilliant, the plants more delightful, the birds more charming, the animals more pleasing, and man more noble.

The concept of great art as triumphant over nature was a borrowing from Vasari, who had in turn borrowed it from Aristotle, and was one of the commonplaces of Renaissance critical theory. We may have more sympathy with the early nineteenth-century essayist William Hazlitt who used the word ‘gusto’ to evoke a quality of Titian’s landscapes that impressed him: ‘a rich taste of colour is left upon the eye, as if it were the palate, and the diapason of picturesque harmony is felt to overflowing. “Oh Titian and Nature! Which of you copied the other?”’ And he added: ‘We are ashamed of this description, now that we have made it, and heartily wish somebody would make a better.’24

Perhaps the most successful translation of Titian’s painted landscapes into words was written in the early 1540s by his closest friend and most sensitive critic, the writer, journalist and failed painter Pietro Aretino, in a letter about a visit he had recently made to an idyllic countryside. Although the place he had visited was actually Lake Garda, the landscape he described could, as Aretino knew better than anyone, have been painted only by Titian, the greatest master of the alchemical art of transforming real, raw nature into high art. Aretino painted in words the abundance of flowers, the trees, songthrushes escaping from their branches ‘to fill the sky with harmony’, racing rabbits, a church, a wine press, the ring of a lake ‘fit to be worn on the right hand of the world … I walked for miles, but my feet didn’t move, behind hares and hounds, around clumps of mistletoe and netted partridges. Meanwhile I thought I saw something that I might have, but did not, fear: beyond the dense undulating mountains, and hills full of game, were a hundred pairs of spirits obedient to the power and magic of art.’25