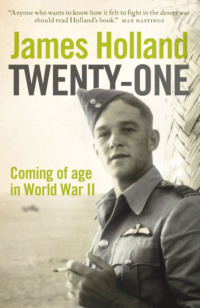

Twenty-One: Coming of Age in World War II

TWENTY-ONE

Coming of Age in the Second World War

James Holland

Dedication

For Jimmy P

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Dedication

Introduction

TWINS

Bill & George Byers

Tom & Dee Bowles

VILLAGE PEOPLE

Dr Chris Brown

Bill Laity

FRIENDSHIP

John Leaver & Fred Walsh

LOVE AND WAR

Warren ‘Bing’ Evans & Frances Wheeler

DERRING-DO

George Jellicoe

FIGHTER BOYS

Roland ‘Bee’ Beamont

Ken Adam

SPORTING BLOOD

Tom Finney

THE SHADOW WAR

Gianni Rossi

Lise Graf

BENEATH THE WAVES

Michael ‘Tubby’ Crawford

THE HEROIC ALLY

Wladek Rubnikowicz

BOY TO MAN

Hugh ‘Jimmy’ James

PARATROOPER

Heinz Puschmann

THE LAST BATTLE

Bill Pierce

Acknowledgements

Other Works

Copyright

About the Publisher

Introduction

When Roland Beamont turned twenty-one, he was already a veteran of the Battle for France and the Battle of Britain, had shot down a dozen enemy aircraft, and won a Distinguished Flying Cross. A year later he was a squadron leader with over sixty pilots and groundcrew under his command; before he was twenty-four, he was in charge of an entire wing of three squadrons, operating a brand-new aircraft that he personally had played a significant role in developing.

Today in the western world none of us is forced to spend the best years of our life fighting and living through a global war. International terrorism may be a cause for worry, but it has directly touched few of our lives so far. For the generation who were born from the embers of the First World War, however, coming of age offered little cause for celebration. Youth was sapped as the young men – and women – were forced to grow old before their time. Mere boys found themselves facing life-threatening danger and the kind of responsibility few would be prepared to shoulder today.

These people were an extraordinary generation. The majority of those who fought were not professionals, but civilians who either volunteered or were conscripted as part of a conflict that touched the lives of every person in every country involved; ordinary, everyday people. One of the fascinations of the Second World War is wondering what we would have done were we in their shoes. Would we have willingly answered the call? Which of the services would we have joined? And would we have been able to control our fear and keep ourselves together amidst the chaos and carnage? Or would we have crumbled under the weight of terror and grief? ‘How did you deal with seeing friends killed in front of your eyes?’ is a question I have asked veterans over and over again. ‘You simply had to put it out of mind and keep going,’ is the usual reply. Would we have been able to do that in an age when we like to demonstrate mass expressions of grief and to turn to counselling as the panacea for any trauma? One veteran who had survived much of the war in North Africa and then the bloody slog up through Italy told me how when his house was recently broken into, someone offered him victim-support counselling. ‘I told her to bugger off,’ he said.

Nonetheless, most veterans believe we would behave exactly as they did. I would like to think so, but am not so sure. It was hard growing up in the 1920s and 30s. In Britain and the Commonwealth countries, communities had been devastated by the losses on the Western Front or at Gallipoli. In the United States, the Great Depression touched the entire nation; appalling poverty was rife. Healthcare was in its infancy and the standard of living – both in the USA and Europe – was way, way lower than it is now. Of the many I have interviewed, over fifty per cent had lost at least one parent by the time they were fifteen. Corporal punishment was a part of every child’s life. For the privileged, nannies and household staff ensured that parents often remained distant figures, while among the poor, a child might share a bed with his siblings and a bedroom with his mother and father. This is not to suggest that the twenty-one-year-olds of the war generation loved any less than we do today, or had fewer feelings; of course they did not. But perhaps their expectations were lower. Perhaps they were used to hardship in a way that is unfamiliar to us today. For those in Britain and her Dominions, the post-Great War generation also grew up during a time when wars and conflict were a part of British life. Even after the slaughter of the First World War, there were still plenty of Empire spats: in Ireland, Afghanistan, and along the North-West Frontier. Iraq. And while during the inter-war years, the United States largely stuck to her isolationist policy, life was every bit as hard in America, if not more so, than in Britain.

Perhaps we are too soft in this age of Health and Safety, when the threat of litigation means we are mollycoddled and protected more than ever before. Certainly we are less interesting. For all its horrors, no one can deny that the Second World War provided human drama on an enormous scale. The First World War, despite the terrifying ordeal of the trenches, did not touch as many lives as the war of 1939–45, where in Europe, certainly, the majority of civilians, as well as combatants, found themselves in the front line. Britain suffered considerable aerial bombardment, severe rationing, displacement of many thousands of men, women and children and dispatched its young men all around the globe to fight for a better world. By 1945, the United Kingdom had sent off so many men to war that there were almost no reserves of manpower left. Yet compared to Germany, Italy, Russia or Eastern Europe, Britain got off lightly. So, too, did the United States, but this is not to demean their huge losses. Of the front-line formations in northwest Europe and Italy, America suffered 120 per cent casualties between D-Day and VE Day. In the Pacific, the trauma for US troops was even worse, where they suffered unimaginable horror as they battered their way from one tiny dot in the ocean to another. The Battle for Okinawa, raging while in Europe the Allied armies were enjoying the fruits of victory, was one of the bloodiest, if not the bloodiest, battle of the entire war.

No one in their right mind would wish another world war, but no matter how terrible it may have been, many who lived through it will also admit that when facing death every day, they never felt more intensely alive. When one said goodbye to friends or family, one might well be doing so for the last time, so worrying over trivialities was pointless, and petty disagreements and squabbles were often cast aside. Carpe diem was not a catchphrase but a state of mind, and this meant that most people were far better at living back then than we are today. Communities were drawn together by the war. Britain as a whole was more united than it has been since; the same can be said of the United States. There was a collective understanding that the burden of war needed to be shared. This has long gone. As every year takes us further away from the war, so we become more selfish, more materialistic, more interested in the minutiae of life.

For those in the firing line, the war also provided extraordinary bonds of comradeship, that special link between brothers in arms that can only be forged in wartime; it is something that cannot be experienced or truly understood by those who have never seen active service, as any combat veteran will tell you. For all the death and destruction that surrounded them, this bond was a positive, something they have experienced that has enriched their lives; something they keep for ever.

This is not to glorify war, however. One can appreciate some of the human qualities and priorities of wartime without feeling nostalgic for a time when millions of people were being killed, wounded and severed from their homes and families. Nonetheless, it is the positive aspects of war that, understandably, many veterans like to think about in their twilight years: this is basic human instinct. There is also no question that only in the last fifteen or twenty years have many of the veterans begun talking and writing about their experiences.

After the war, most wanted to get home and get on with their lives. Find a job, marry, have kids and settle into ‘normal’ life once more. They never thought of themselves as special because everyone had been in the same boat. Only once they had retired, with their children flown the nest, did they have the time to really analyse what had happened to them. Most veterans tell me the same: ‘I never really talked about it until I was in my seventies when I started going to reunions.’ Perspective takes time. A period of quarantine is needed. Most veterans need maturity, not the callowness of youth, to be able to properly weigh up the experience of what happened to them.

There is also a sense that time is marching on. Most veterans are now over eighty and many feel the need to tell their stories before they are gone for ever. And as their numbers dwindle, their experiences cease to be commonplace, but rather special instead. ‘Only now am beginning to realize that what I did back then was pretty incredible,’ one former fighter pilot told me.

The wheel of change has been swift in recent years, which often makes the sixty years since the end of the Second World War seem longer than it really is. Yet talking to many of those who lived through those times soon draws the war closer again. Sixty years is not that long really – we can still touch it through these survivors, and still find inspiration from their heroism.

Those that survive, are, of course, the lucky ones. They have had a chance to live full lives and to grow old. A former German paratrooper visited Cassino in Italy for the sixtieth anniversary of that most terrible battle. He toured all the cemeteries, hugged his former comrades and enemies, and told me the story of his friend who had died slowly in his arms. ‘And here we all are now,’ he said, ‘so what was the point?’ We are fortunate today that we can make the most of our youth. Europe is now united and the United States our ally still. The generation who fought in the war should not be forgotten, not now, while many still live, nor in the future when they are gone. We should learn their lessons and remember and recognize the enormous sacrifices they made.

Bill & George Byers

Shortly after 10 a.m. on Wednesday 3 November, 1943, a cipher clerk at RAF Leeming in Yorkshire received a signal from Bomber Command Headquarters that there would be an operation that night. There was nothing unusual about this – they often came in about this time, after the morning meeting at High Wycombe. A WAAF immediately put a call through to Wing Commander Jack Pattison, CO of 429 ‘Bison’ Squadron, Royal Canadian Air Force. ‘There’s a “war” on tonight, sir,’ she told him. A few minutes later, he was in the operations room himself.

Pattison was handed the fully decoded message in silence. Another maximum effort was being called for; it was ever thus. The target: Düsseldorf, an industrial city that had been designated a ‘Primary Industrial Area’ in the Air Ministry’s directive to Bomber Command early the previous year. Even so, and despite being in the heart of the Ruhr industrial area, the city had been attacked only four times, and not since June. But that night, Bomber Command wanted six hundred aircraft to take part, a large raid indeed. A glance at the board showed that fifteen of their sixteen Halifaxes were fit to fly. Almost maximum strength – and that included the CO and his crew flying as well.

Flight Sergeant Bill Byers wandered over to the Flight Room at around 10.30 a.m., and there learnt that he would be going out that night. A notice on the board merely warned them that they were under battle orders, but nothing more – no clue to the destination or size of the raid was given. He immediately went to see the meteorological officer to try and find out what the weather was due to be like over Europe, then called his crew together. Once assembled, they took a truck – or a blood wagon, as they were known – over to their aircraft, ‘Z’ for Zebra, so they could run up the engine and go through the pre-flight tests. It was a grey, damp, cold day – the kind of day that never really grew light – and drizzling slightly. Mist shrouded the airfield. The Halifaxes around the perimeter loomed like spectres. Most of the other crews had followed suit, and despite the chill stillness of the day, RAF Leeming was now a hive of activity. As well as the jeeps and trucks rumbling by, trolleys of bombs, fuel bowsers and ammunition carts were all hurrying to the dispersal areas.

Not far away, Bill’s twin brother George was going through the same process with his crew. The brothers had only been with the squadron a month but were already considered quite a unique pair at Leeming – after all, there’d not been identical twins at the station before. Moreover, not only did they look exactly the same, they were also practically inseparable, apart only when with their respective crews and in the air. They even shared a house together. On their arrival they’d been allocated a married quarters house in Leeming. Dick Meredith, Bill’s wireless operator, shared the house with Bill and George. The twins took a room upstairs, while Dick and several other crew members took rooms downstairs. ‘They were so much alike, you could barely tell them apart,’ recalled Dick when I spoke to him some time later. ‘And so close. They never said, “Where’s my shirt or socks?” but “Where’s our shirt?”’

Shortly after the pre-flight tests, it was time for lunch – a simple but nutritious hot meal, followed by chocolate or biscuits. Bill would always take a bar of chocolate and a tin of apple juice with him on the mission, but it was important to make sure the crews were well fed before they took off. The food was a perk of the job – and there needed to be some – for while most in Britain struggled with the stringent rationing, there were fewer shortages for the bomber boys. Bill and George ate their meal with Dick Meredith and some of their other crew members in the sergeants’ mess. Strangely, although the twins were the captains of their aircraft, they were not officers, even though two members of their respective crews were, and messed separately; the social divide between officers and non-commissioned officers might have been put to one side in some theatres of the war, but not so in Britain. Not everyone felt like eating a heavy meal – nerves and apprehension gave people a nauseous sensation in their stomachs. The key was to try not to think about it too much, and to keep the conversation going. Distraction was everything.

Between the end of lunch and the final briefing there was not much time – the chance for a quick game of cards, or to write a letter, but not much more. In the Flight Rooms, they would put on silk underwear, thick pullovers and flying boots, then head to the Briefing Room. There, all the crews came together, not just from 429 Squadron, but 427 ‘Lion’ Squadron as well, also based at Leeming: pilots, navigators, flight engineers, air bombers, wireless operators and the air gunners, piling in and scraping back chairs as they sat down. Since that first message earlier in the day, more information had reached Leeming about the route, the bomb loads required, timings, and, crucially, frequent weather updates. In the Briefing Room, there were rows of desks on which pilots and crews could make notes, while on the end wall was a large map, covered over with a cloth until the Station Commander came in and announced the destination. This could be an anxious moment: the further away, and the deeper into Germany the raid, the more dangerous it was. Then the Navigation Officer spoke, explaining the forming-up procedure and the route to Düsseldorf, marked on the map with lines of white tape. The Met Officer was next. Despite the low cloud over northern England, the target area was, he assured them, expected to be clear. Bill listened carefully, jotting down a few notes on a scrap of paper. This was only his second mission as skipper and he felt his stomach tighten.

The briefing over, the crews collected the rest of their kit – flight suits and Irvins, flak jackets, Mae West lifejackets, as well as chocolate and apple juice, then clambered once more into the blood wagons and set off for their aircraft. It was nearly four o’clock by the time they reached their Halifaxes, and the light was already beginning to fade. Once aboard their aircraft they waited for nearly half an hour. In the cockpit, some twenty-two feet off the ground, Bill went through final checks. It was cold in there, without the heat from the engines to warm it up. It smelled of metal, dust and oil. And it was quiet; there was no more joking, no laughter. The mood amongst all the crew was now serious, their thoughts directed to the job in hand. Christian names and nicknames were replaced with their proper titles: Navigator, Upper-Mid Gunner, Skipper – with communication through the aircraft’s intercom. The minutes seemed to have slowed. As Bill was discovering, this half-hour before they took off was the worst part of the whole trip. He felt scared – of course he did. Anyone who said they weren’t was a liar as far as he was concerned.

At last the signal came and Bill started the four Rolls-Royce engines, licks of flame flicking from the exhaust outlet brightly against the darkening sky. The great aircraft shook and they moved into line, taxiing onto the perimeter track running around the left side of the airfield. Further away, 427 Squadron were lining up on the right. The first Halifax from 429 thundered down the runway at 4.25 p.m., then off went a plane from 427, the two squadrons feeding in turns from their respective sides of the main runway. Bill inched his aircraft forward. George was two ahead. At a quarter-to-five, he watched his brother reach the top of the runway, pause, then accelerate and lumber into the air. Three minutes later, it was his turn. As he taxied round, he saw the usual groups of groundcrew and WAAFs along the edge of the airfield. As Bill pushed open the throttle and felt the Halifax clatter and surge forward he could see them waving and holding their thumbs up in a sign that meant good luck. With both hands, he gently pulled back the control column and felt the Halifax lift from the ground, the perimeter hedge disappearing beneath them. Trees, roads, villages rushed by and then they were in cloud and climbing high into a dark and uncertain sky.

The first time I met Bill Byers was on a warm but blustery day in May 2002 at Croft Racing Circuit in North Yorkshire, England. He was there with a number of veterans and their families for the unveiling of a plaque dedicated to the men of the Royal Canadian Air Force who had flown from there during the war. I noticed Bill because he stood out so obviously from the other veterans. Wearing a baseball jacket and cap, he moved about easily and when he talked it was with a quiet but animated Canadian accent that sounded many years younger than his eighty-two years. Wandering over, I introduced myself and we soon got chatting. He’d only been at Croft a short while during the war. It was not long after his arrival in Britain in the summer of 1943. He and his identical twin brother George had been sent there to convert from twin- to four-engine bombers. After that they’d both joined 429 ‘Bison’ Squadron, RCAF, based down the road at Leeming, flying Halifaxes. He told me about the weather that winter. ‘Boy, it was cold,’ he said. When it wasn’t snowing it was raining. Because they always flew their bombing missions at night, the lack of sunshine started to really get him down. At one point, he realized he’d not seen a hint of sunlight in over two weeks, so with no ops that evening, told his crew they were going for a practice flight and took them high above the clouds. ‘I just needed to see some sunlight,’ he told me. ‘We flew up and down the country, and felt much better after that.’

We were still talking when someone started pointing to a dot in the sky beyond the trees at the end of the circuit. Then we heard the faint thrum of engines and in what seemed like no time at all, the Battle of Britain Memorial Flight’s Lancaster was humming past. After one flypast we began to talk again, but then the Lancaster slowly banked and turned in for another sweep over our heads. Everyone gazed skywards, mesmerized, as it then circled again and came back for a third pass. Once it had disappeared over the horizon, I turned back to Bill who introduced me to his wife, Lil. They’d met during the war. She had been a young girl from nearby Northallerton, and when Bill finished his combat tour they’d got married and after the war she’d journeyed with him back to his native Vancouver.

‘We’ve made the trip back to England about twenty times since the war,’ Bill grinned. ‘I love it here. And you see, my mother was English too. She met my dad during the First World War, so I’ve always felt attached to the place.’

We met again some eighteen months later at their home in Redwood City, a few miles south of San Francisco in California. It was a couple of weeks before Christmas, but in Carmel Drive it was warm and, for the most part, sunny. They’d moved there over forty years ago – his job with the Post Office had been ‘boring as anything,’ and his cousin, Hal, had always wanted him to come on down to California. So finally that’s what they did, with Bill buying into Hal’s masonry business in November 1959. It turned out to be a good move. ‘We did reasonably well,’ Bill told me, ‘and we’re secure financially. We’ve been able to do what we wanted to.’

He suddenly leant forward, his fingers together. There was still a lot of energy there; he never seemed to sit still for long. ‘But you want to hear about the war,’ he said. ‘What do you want to know?’

Let’s go back to the beginning, I suggested. I was interested to know about his background, about what shaped him, and what led him to fly bombers from an icy airfield in northern England.

There were no other brothers or sisters, just Bill and George. ‘My mother’s first husband was killed during the First World War,’ said Bill. ‘Then she met my dad and followed him back to Canada. Then my brother and I were born.’ His dad was in lumber mills, for most of the time working around Vancouver, although when the twins were six, they moved to Burbank in southern California for a few years before returning to Canada. Their childhood was, he admitted, pretty happy. He and his brother did most things together and although they had occasional spats, were very close most of the time. ‘Our thoughts were often identical,’ said Bill. ‘Whether it was some kind of telepathy I don’t know, but if we thought about some problem, we’d be sitting there looking at each other and both get the same idea at the same time. That would happen loads of times.’ Neither was particularly keen on class work and they took far greater interest in woodwork and the more practical subjects. ‘I hated Shakespeare until I got to England,’ said Bill. ‘Now I think he’s the greatest.’ They left school and both went straight into a course in aeronautics, part of the Dominion Provincial Youth Training Scheme. They’d been there about six months when war broke out. The RCAF was soon recruiting hard and both Bill and George were accepted, although as groundcrew rather than pilots. Their training took them to bases all around the country, but they were at Saskatchewan when they turned twenty-one. ‘It wasn’t a big deal at all,’ said Bill. ‘In wartime they don’t give you a day off for your birthday.’