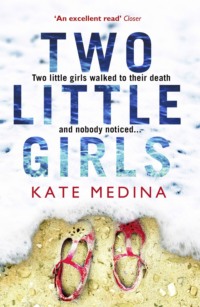

Two Little Girls: The gripping new psychological thriller you need to read in summer 2018

‘Except that the bible doesn’t agree,’ Laura said.

Seven deadly sins.

‘It was my fault.’

Jessie shook her head. ‘No. We’ve talked through this, Laura.’ Countless times. And they would, she knew, countless more. ‘It was an accident, plain and simple. An accident with horrible consequences that you would have given everything to be able to prevent, but still an accident.’

‘That’s a mother’s job, isn’t it, though? To protect her child from harm. That above anything else, the one and only vital job. You can fail at all the others, but not that one. Not that one.’ Laura rubbed her hands over her eyes, smearing the welling tears across her cheeks. ‘I succeeded at everything else. All the stuff that I thought was so bloody important back then. Writing her name before she’d even started in Reception, reading level 4 Biff and Chip books by the Christmas holidays, number bonds to ten by Easter, even though learning was such a struggle for her. But it wasn’t important, was it? That was all a big fat lie.’ Her face twisted with anguish. ‘And the one thing, the only thing, the only critical job was the one I failed at. The job of keeping her alive.’

Jessie had faced her fair share of grief, her own and other people’s, patients’, in bland consulting rooms like this one, but the grief pulsing from this woman felt different. Like the grief she had felt from her own mother when her little brother, Jamie, had committed suicide. Grief and guilt. The overwhelming emotion – guilt. And something else too, something she couldn’t put her finger on. Why wouldn’t Laura look her in the eye, even momentarily? Still?

‘Laura.’

She nodded. She looked worse than the last time Jessie had seen her, just a week ago. Exhausted, thinner, if that was possible in such a short time, the black rings under her eyes so dark, they looked as if they had been charcoaled on. She reminded Jessie of a pencil sketch: there, but almost not.

‘It wasn’t your fault, Laura. None of it was your fault.’

3

The woman screwed her eyes up against the rain and the wind that drove it horizontally into her face and lashed the wet dregs of her blonde hair around her cheeks. She was alone on the beach, and that was how she liked it.

The gunmetal sea lapping the sand was deserted also; certainly no pleasure boats out this afternoon, but no ships either that she could see, visibility misted to a few hundred metres offshore, the primary colours of the rides at Hayling Island funfair across the mouth of the harbour resembling washed watercolour strokes on grey paper.

Weather like this caused holiday-makers to bolt for shelter. Duck into the cafés and restaurants on Shore Road, their steaming waterproofs draped on the backs of chairs while they had tea and cake; or potter around the pound shops in East Wittering village, throwing a fiver at their kids’ boredom until the rain stopped or the shops closed, whichever happened first. There were too many people during the summer months, which was both a curse and a bonus for her. She watched them with suspicion and they watched her with more, used to seeing tanned, long-limbed girls in surfer T-shirts and board shorts at the beach, not the kind of woman they’d expect to see begging for coins around train stations in grotty town centres or rifling through the ‘past sell-by date’ bin in budget supermarkets.

She had mixed feelings now that the summer holidays were nearly over. She despised the tourists who arrogantly commandeered her beach with their hoards of possessions and their loudly advertised happiness. She hated them, but their presence occasionally brought her a windfall: things deliberately discarded, others left accidentally, having slipped from overflowing beach bags or dropped from baggy pockets. Items she could use, barter or sell. Days like this were good, rain following sun. She didn’t mind the miserable weather because it cloaked her in solitude. Solitude was comfortable to her – she knew nothing other than loneliness. There had been only a brief period in her life when she hadn’t been on her own, a wonderful, fleeting time that had changed everything.

The woman looked from the stormy horizon to the little girl lying in the dunes at her feet. The sand was white, the little girl’s skin whiter, as if she had been washed sparkling clean by the rain. The tinny tune of a washing powder advertisement from years ago, from when she had used to be parked in front of the television for hours on end as a girl herself, chimed in the woman’s dulled brain.

Little girl, far away in a world of your own, in a world built of dreams that are yours and yours alone.

She had wanted to be the girl in that advert. That perfect, soft focus blonde child playing in a meadow full of wild flowers. She had wanted, so desperately wanted, the crisp white broderie anglaise dress the little girl was wearing. But though she was blonde and fair-skinned, she had never owned a dress like that, never seen a field of grass, just the scrappy patches of dirt dotted around the tower blocks where she lived, where kids skidded their bikes and teenagers smoked and fucked. She had never seen a meadow, cows, sheep, horses; had never seen any animals aside from the pumped-up dogs dragged around on studded leather leads and the rats that scurried around the bins at night.

The eyes of the girl with the perfect white skin were open, staring fixedly up to the sky as if her gaze had been caught by one of the seagulls hovering above them on an updraught. They were cloudy green like the sea on a cold, clear day. Her hair was brown and curly, so dark against the sand and her own white skin that it looked as if her head had been caught in a halo of dirty seaweed.

Little girl, far away in a world of your own, in a world built of dreams that are yours and yours alone.

A doll lay next to the girl. A nasty plastic doll dressed in a cheap pink ballerina dress, with eyes that the woman knew would move if she lifted it. The doll’s eyes were green like the girl’s.

You’ve always been a quiet one, but I don’t know, it doesn’t seem to keep you any cleaner.

Shells ringed the child and the doll in the shape of a heart, a heart even whiter than the sand and the little girl’s washed white skin. It was so long since the woman had considered love, felt love, that the shape of the heart knifed, just for a second, into a part of her that she had long since shut and padlocked. She shook her head, trying to shake off the memory and the feelings the sight of the little girl and the perfect pale heart surrounding her had brought to the surface.

Extending her foot, she nudged her toe against one of the shells, knocking it out of kilter, against a second, third and fourth, kicking them out of line too. She smiled to herself, a small, satisfied smile. The heart was broken now and that was better. A broken heart reflected the life that she had lived. The life this little girl would doubtless have lived, had she lived. Real hearts were for television advertisements and soppy songs written by fools.

Bending down, she fingered the necklace around the girl’s neck. It was a silver locket; antique, from the look of it, engraved with two sets of footprints: those of an adult and, next to them, the smaller prints of a child. The silver was cold and her thumb pushed the wet from the engraved metal and left a dull print that was swallowed by raindrops the instant she pulled her thumb away. It would be worth something that, but she wasn’t going to take it. She had her reasons for not stooping to that. For not taking a necklace off a dead child. Beneath the necklace’s chain of silver coiled another, the thick dark chain of a bruise. Apart from the bruise, starkly black and purple against the soft white skin, the little girl looked untouched. Alabaster.

The woman stared down at the dead child and thought that she would feel something.

Sadness? Horror? Anger?

Or nothing? At least – nothing.

But what she felt was worse. It was a feeling that she recognized as satisfaction. Satisfaction that someone else would hurt the way she hurt every moment of every day. Cruel. When had she become so cruel as to enjoy someone else’s grief?

Little girl, far away in a world of your own, in a world built of dreams that are yours and yours alone. Though I cannot share your dreams, you are still my very own.

A small part of who she was – who she used to be – hated herself for the feeling. But that person was so far gone that she existed in another life, a life that had happened to someone else, and the tiny nugget of self-hatred was easy to ignore.

She looked down at the bruised tracks on the underside of her forearm, the soft skin there almost as white as the dead child’s, the needle marks dark as the snake of bruises coiled around the child’s neck. The woman had lived by the sea all her life and she recognized weather patterns like she recognized those self-inflicted patterns on her arm. The rain had set in for the evening, at least. There would be no one else to disturb the quiet of the dunes today, walking where she had walked. She didn’t need to rush. There was no urgency to tell the police. The little girl was dead. She would stay right here in her heart of shells and the doll with the matching eyes would keep her company.

Pushing herself to her feet, stepping carefully around the prone child, the woman walked on, the wet sand clinging to her bare soles, rainwater slopping around her toes. A packet of cigarettes caught her eye, damp, sodden, but she could dry them. Bending, she slipped them into the pocket of her jacket. A little further on, a two-pound coin, spilled from a purse or pocket. Lucky. A lucky day, for her at least. September seventh. Lucky seven.

Straightening, she walked on, eyes grazing the sand for treasure, leaving the dead child behind her alone in the dunes, staring up at the sky, staring up at nothing.

4

Icy water stung Carolynn’s cheeks as she fumbled the front-door key into the lock with one hand. The plastic handles of the grocery bags cut into the wrist of her other arm; usually she would have set them down on the ground, but the path at her feet was sodden. It hadn’t been raining when she’d left the house mid-afternoon for her run, but the sky had been a uniform ceiling of grey, so she had slipped her waterproof cagoule over her lycra tights and tank before she’d set out.

Roger’s car wasn’t on the drive so he must still be at work. Though she preferred it when he wasn’t home, the thought of stepping into that oppressive little house, alone once again, made a sick feeling balloon in her stomach. Today of all days, she couldn’t bear to be out among the crowds – couldn’t trust herself to be in enclosed spaces with families, bracing herself against the sound of children’s voices rolling in from down the street, or from another aisle in the supermarket. But now that she was alone, with no external stimuli to distract her, her mind was flooding with memories, pictures so vivid that she felt faint, knocked sideways with the pain.

Unbidden, an image from her visit to the beach that morning rose in her mind: the little girl in a pastel pink bathing costume. Where would she be now? With her parents and sisters, eating Nutella pancakes at the surf café? Tucked up on a sofa in a rented holiday home watching cartoons? Playing board games in a hotel lounge? Normal rainy-day holiday activities that she would never again do with a child of her own. Her goal when building her family had been to have pretty, bright, well-mannered children, to want to spend quality time in each other’s company, to relish every single, simple moment. The thought of that dimpled little girl on the beach hurt like a weeping sore.

It wasn’t my fault, she screamed inside. You need to believe that it wasn’t my fault.

Grocery bags knocking around her bare ankles, she staggered into the kitchen and laid them on the clay-tiled floor. On a dull early evening like this, even with all the ceiling spots on, the kitchen was unbearably claustrophobic. Dirty cream walls and dark wood kitchen cabinets topped with black laminate work surfaces shrunk it to half the size it actually was, making her feel as if she’d squeezed herself into a cardboard box.

The house was a rental. A small white house jammed between the gate of a static caravan park on one side and a boarded-up, crumbling bungalow on the other. It was right by the sea, but you wouldn’t know it, except for the stream of tourists wandering past in the summer, shouldering beach bags and clutching ice creams, and the brutal weather that rattled the window panes in winter. From the kitchen window, she could see the road and beyond that the concrete sea wall that wouldn’t have looked out of place bordering a military bunker. It had been built head high and a metre thick to prevent the sea from eating up more land, but she couldn’t see the point of being by the sea if you couldn’t appreciate its beauty. And she did love the sea. Cheap and faceless, this was a running-away-to house, a hiding-away-in house. They had only planned to be here a couple of months until the furore surrounding the court case had died down and they’d decided how and where to rebuild their lives. But their London house hadn’t sold – prospective buyers put off by having seen it on television for all the wrong reasons – so their hands were tied.

Hauling the fridge door open, Carolynn listlessly filled it with the shopping, every bend and straighten a gargantuan effort. She felt physically and mentally exhausted, wrung out like a damp dishcloth. She had eaten nothing all day and yet she wasn’t hungry, was rarely hungry these days. She had to force herself to eat enough to keep her body grinding along.

As she flicked the kettle on to make herself a cup of tea, the cat jumped on to the island, leaving a trail of dusty paw marks from its litter tray across the black laminate surface. Revolted, Carolynn fought the urge to swing the full kettle from its stand and knock the bloody animal to the floor with it. The cat had been Zoe’s, a Burmese, bought for her by Roger’s mother because ‘every child needs a pet’. Carolynn hadn’t needed to ask the subtext. Every child needs someone or something they can love unconditionally, that loves them back without reserve or judgement.

Didn’t your husband become so alarmed about your ambivalence towards your daughter that he asked his mother to move into your house to look after her?

No.

And did his mother not live with you for a full eighteen months, from when Zoe was a year old until she was two and a half, until her husband, your father-in-law, became ill and she had to move back to her home to look after him?

No. It wasn’t like that.

She’d tried hard to put her struggle with motherhood, all those negative feelings she’d had, behind her by the time Pamela bought Zoe that repulsive cat. She was four then. Pamela had used her fourth birthday as an excuse for the purchase, but Carolynn knew the real reason. Why were people – her own mother-in-law, for Christ’s sake – still treating her as if she couldn’t manage, couldn’t be a proper mother, even then? And why did Roger let Pamela behave like that? Shouldn’t he have supported her, his own wife?

Thereafter, did your husband not employ a full-time live-in au pair, even though you were not employed yourself? I put it to you that it was because he was worried about his daughter’s safety if he left her with you alone. With her own mother.

That’s not true.

You had severe depression, didn’t you, Mrs Reynolds?

No. No, I didn’t.

The prosecuting solicitor had kept interrupting her. Arrogant. He was so arrogant, he wouldn’t let her speak.

Absentmindedly, she reached out to stroke the cat, but it arched its back, bared its teeth and hissed at her. God, even the cat hates me. The cat who’d been bought precisely because Burmese cats were as loving as dogs. She’d see it sitting on the garden wall, letting every damn stranger who walked up the street pet it, rubbing its head against their hands; she could hear its purr even through the glass window. And yet it couldn’t abide her.

You were referred to a specialist mental health team because you had such severe depression.

Making a huge show of putting on his glasses, letting the jurors’ minds linger on the words ‘specialist mental health team’, as if she was mad. He wanted them to think that she was mad. He hadn’t understood. None of them had understood.

Depression brought on by motherhood. Isn’t that true, Mrs Reynolds?

There was nothing strange about postnatal depression, so why had they used it against her in court? Tried to insinuate that she was crazy? Mental health was an issue for many people. Some philosopher she’d read had summed it up beautifully. She couldn’t remember the exact words, but it was something about most people leading lives of quiet desperation. Life was mainly struggle, wasn’t it? Hardly surprising then that so many people succumbed to depression, as she had done. She had found motherhood tougher than she had expected it to be. She hadn’t fallen crazily and unconditionally in love with Zoe. Those weren’t crimes.

Reaching for a tea towel, she flapped it at the cat, which arched and hissed again and then leapt to the floor, scooting a wide path around her legs to dodge the kick she launched at it. She’d find a furry patch on one of the cream sofa cushions in the sitting room later, no doubt. Have to wrap Sellotape around her fingers and pat her hand across the patch to collect up all the stray hairs, pick up the few that had stuck, like pine needles, in the cream cotton with her nails. Roger liked the house clean. We both do – it’s not just him.

The kettle had boiled and she made herself a cup of green tea, paced as she sipped it, too stressed and upset to sit down, sit still.

September seventh.

Lucky seven.

Seven detestable sins.

She hadn’t told Dr Flynn in her session this morning that, besides Roger and the odd impersonal interaction with people in shops around the village, she was the only living adult Carolynn spoke with all week. That she would talk properly to no one, bar her husband, until next week’s session. That the sessions were rapidly becoming a beacon of light for her; her only beacon. She recognized a kindred spirit in Jessie Flynn. Flynn wouldn’t tolerate a filthy cat padding over the surfaces in her kitchen. Those surfaces would be spotless – spotless and bright white. Everything in Flynn’s house would be white, Carolynn imagined, and immaculate, just as her own house had been, back when they lived in London.

Though she was sure that Jessie would be able to disguise her Obsessive Compulsive Disorder from less perceptive patients, she couldn’t hide it from her. Carolynn recognized OCD when she saw it, shared that desire for cleanliness and order, even though she wasn’t a fellow sufferer. She would like to be friends with Jessie. She needed a friend, desperately. Someone who she could talk to, someone who would understand. They couldn’t just keep running and hiding. Keep telling lies.

5

The seagulls were agitating Detective Inspector Bobby ‘Marilyn’ Simmons, unsettling him. There was a flock of them, circling overhead, like vultures orbiting a carcass, as if they knew there was a dead child inside that tent, as if they could smell the blood, sense death.

Later, he would accept that they were attracted by the people, himself included; a Pavlovian response after a summer of beachgoers tossing chips, burger buns and the fag end of sandwiches in their direction. But the sight of them, that ear-splitting squawking, made his nerves and the hairs on the back of his neck stand on end. He was tempted to grab a handful of stones and hurl them up into the sky, throw stone after stone until every single one of the vile creatures had scattered, but that would give the smattering of reporters who had got the early wire about the little girl’s murder exactly what they wanted: DI Simmons demonstrating he was taking this case far too personally. Day one, an hour in, and already it had burrowed right under his skin. Even if he could continue to kid himself that he wasn’t yet drawing parallels with Zoe Reynolds’ murder – two years ago today, he had realized a micro-second after he’d heard that the body of a young girl had been found on West Wittering beach – the press wouldn’t be so forgiving. They would forensically examine in print any actions on his part that weren’t entirely by the book, seizing on anything that could be interpreted as proof that he wasn’t coping, that he couldn’t be objective.

Stripping off his overalls and overshoes and handing them to a CSI officer, Marilyn turned his collar up against the spitting rain and slid down the dunes on to the tidal flats, sucking the salt-laced air deep into his cigarette-ravaged lungs, grateful to be out of that claustrophobic InciTent and away from the sad, desecrated little body. Her green eyes were clouding over with a death film already, wide open, but seeing nothing, recognizing nothing.

Though civilization was barely five hundred metres away – £5,000,000 houses owned by city bankers who had cashed in their chips and retired down here with their families for the quiet life, others heading here at weekends – it always surprised him how startlingly remote this peninsula was, tied to the main stretch of the beach by a narrow bar of sand and extending like a bloated finger into the mouth of Chichester Harbour. Fifty acres of silky soft sand dunes topped with knee-high marram grass where children could play for hours, disappear for hours, even when the beach in front of the dunes was packed with holiday-makers. The local police had fielded many calls over the years from frantic parents whose children had gone missing on this stretch of coast. Most turned up an hour or two after they’d disappeared, having simply lost track of time. Years ago, when he was starting out in the force as a PC, before he’d had his own children and experienced parental worry first-hand, he’d done his fair share of trudging through these dunes, sand penetrating his brogues and gritting between his toes, calling out Noah or Amelia’s name, itching to clip the little sod’s ear when he or she was finally found.

The location should have been God’s gift for footprints, but that forensic avenue had been frustrated by the time of year and the weather: a rainy afternoon following on from a sunny morning and a string of sunny days before that, at the end of the summer holidays. Adults and children’s footprints criss-crossed his crime scene as if a herd of demented cattle had passed through; it would have taken forever to process each and every one, had the rain not obliterated the whole lot.

What was the little girl doing all the way out here anyway? Had she been in the dunes when she met her killer? Had she come under her own steam, playing with friends or wandering alone, or had she been brought here? And if she’d come with her killer, had she done so voluntarily, or had she been bribed or coerced? Easy to bribe a child of that age with sweets, easy to force them with threats. Simple for an adult to convince a child who knew them well to come and play on the beach for an hour.

According to the initial estimate from Dr Ghoshal, the pathologist, she had been dead for between one and two and a half hours, which meant that she had been killed sometime between three-thirty and five p.m. Whoever the child’s killer was, he or she had chosen well, both in terms of location, weather and timing.

He didn’t even know who she was. Only nine or ten years old and yet no one had come forward to claim her. For Christ’s sake – what kind of home did the poor little mite come from?