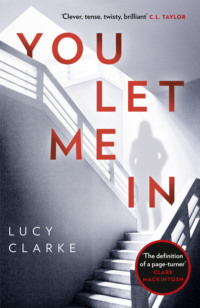

You Let Me In: The most chilling, unputdownable page-turner of 2018

It was all so unlike me – the me who drifted through my twenties owning little more than I could squeeze into a backpack. But I wanted it more than anything. Cornwall was where Fiona was. A house overlooking the sea was our mother’s dream. It was putting down roots, it was stability.

One evening, mid-build, when I’d returned to our rented flat in Bristol, Flynn kept his back to me, watching the flames dance in the fireplace, as he’d said, ‘I wonder if you’re putting too much energy into that house.’

That house. Never our house.

I wish I’d noticed the distinction back then.

I replied, ‘I want to make it perfect, so we never have to leave.’

‘Thank you for looking after things while I was away,’ I say to Fiona. ‘The house looks immaculate.’

‘Surprised?’

‘Very.’

‘It’s because I hardly had to do a thing. It was spotless.’

‘Was it? I was worrying about it while I was away. It just felt so strange knowing there was someone in my home that wasn’t me.’

‘I knew you’d be like that.’

Bill was actually the one who’d suggested I rent the house.

‘You know, if money is tight,’ he’d begun while we were barbecuing on the bay one evening, ‘you should think about putting the house on Airbnb over the summer.’

‘Remember my friend Kirsty from university?’ Fiona had asked.

I must have looked blank.

‘The English teacher. Had sex with the headmaster in his office – and a parent walked in.’

‘That Kirsty!’

‘She has a three-bed house in Twickenham and goes away over the school holidays and rents her place. She gets two grand a week for it.’

‘Two grand?’ I crouched down to examine a shell that Drake had brought to me. ‘It’s beautiful, baby,’ I said, planting a kiss on the smooth curve of his forehead, then folding my fingers around the shell. He trundled off in search of more.

‘Everyone’s doing it,’ Bill said. ‘Easy little earner.’

‘Yes, but this is Elle.’ Fiona threw me a look. ‘She took three days to choose the right handles for her doors.’

‘I can handle it,’ I said, grinning.

‘Anyway, don’t encourage her, Bill. You know who’ll have to look after it when she jets off on another book tour and some porn company decides to use it as the location for their next shoot—’

‘God, don’t!’ I laughed.

‘Contract cleaners in that case,’ Bill said.

‘Kirsty puts all their valuables in their study and locks off the room. Easy.’ Fiona plucked a piece of mint from her glass of Pimm’s and tore it between her teeth. ‘You know that place Bill and I stayed at when we went to Pembrokeshire? That was an Airbnb. They left everything. The wardrobes were full of this woman’s clothes. I think she was a ballroom dancer.’

‘Tell me you tried on something sequinned.’

‘She was more Bill’s size.’

‘I do love a leotard,’ he said, patting his stomach fondly. ‘Seriously though, you could charge a fortune for your place. You should think about it.’

And I had. I thought about it as I stared at the final invoice from the builders, my fingers trembling as I tapped numbers into my calculator. Fiona and Bill didn’t know – they still don’t – that I had to remortgage to pay the builders.

So this first Airbnb rental is a trial, a test run. The idea is that I rent out the house again in the summer and bugger off somewhere. My two best friends both live on the other side of the world; Nadia has moved to Dubai to teach English, and Sadie lives on a farm in Tasmania with her husband’s family.

I turn to Fiona, asking, ‘What were the family like who rented it?’

‘Yes, fine,’ she says, setting her wine glass on the lounge table.

‘Did they seem nice?’

‘I only met them briefly.’

I detect a tightness in her tone, which makes me ask, ‘Everything did go okay?’

‘Yes, absolutely. No breakages. I’ve released the deposit. They left a couple of bits and pieces behind.’ As Fiona unfolds herself from the sofa, I notice she’s lost weight. We’ve both always been slim, but there’s something angular about the breadth of her shoulders, her sternum pronounced at the open neckline of her shirt.

Fiona moves to the sideboard, picking up a pot of nappy rash cream, and a well-chewed plastic giraffe.

‘These were the only things I came across,’ she says, squeezing the giraffe until it squeaks.

Unexpectedly, sadness swells in my chest.

‘I’ve washed all the bedding – hot wash,’ she adds with a wink, ‘and taken Drake’s high chair home.’

‘Oh yes, thanks for the loan.’

‘I dropped it in the evening before they arrived and almost had a heart-attack as the alarm was on. I’d forgotten you’d told me you’d set it.’

‘You turned it off okay?’

‘On the sixth attempt. My eardrums bled. Right,’ Fiona says, sweeping across the lounge towards the doorway. ‘I’m going. Told Bill I’d only be half an hour.’

‘Sorry for stealing you.’

‘It’s fine, he has the television. Three’s a crowd.’

I stand and kiss my sister, our cheekbones clashing.

Locking the door behind Fiona, I move into the kitchen, flicking on all the lights and the radio.

I take my notebook from my handbag and position a pencil beside it. I take a step back, looking through the screen of my phone at the configuration. I snap the picture, then upload it to Facebook, adding the caption:

After a lovely fortnight tutoring on a writing retreat, I’m back home and SO excited to be diving into my novel – on the home straight now! #amwriting #authorlife

Then I put the props away.

Opening the fridge, I inspect its contents, hoping Fiona might have left a pint of milk or a loaf of bread – but it’s bare.

Too tired to contemplate getting back in the car, I root around in the pantry and pull out a bag of pre-cooked quinoa and toss it through with tahini and lemon juice. I eat standing up, flicking through the post.

I glance at the bills, trying to ignore the words FINAL REMINDER blazoned across my electricity statement. Next there are a couple of packages from my agent containing proof copies of other authors’ books requesting advance praise. The remainder of the mail includes requests for charity donations, two fan letters forwarded on from my publishers, and an invite to a friend’s birthday. Nearing the bottom of the pile my hands reach for a thick cream envelope embossed with a gold logo. It’s from Flynn’s solicitor.

In France I’d been reminded of our first trip together in our mid-twenties, when we’d taken the ferry to Bilbao and then driven north to Hossegor in Flynn’s battered Seat Ibiza with a surfboard strapped to the roof and a tent in the boot. We’d camped in the shade of thick pine trees and lived on noodles and warm batons of French bread. We drank cheap stubby beers and wine from cardboard containers, and spent the evenings playing cards by headtorch, or lying in the tent, the door unzipped, salt and sun-cream glossing our entwined limbs.

On that trip Flynn had talked about all the places he wanted to travel – and I had said yes to it all, knowing that I wanted to be anywhere but home. When I was with him, the rest of my life seemed like something that had happened to a different person, someone I was happy to leave behind in the campus of a university town I’d never return to.

I scrape the rest of the quinoa into the bin, then collect my suitcase and go upstairs. Flicking on my bedroom light, I pause in the doorway, my gaze on my bed.

Fiona has done a half job of making it, of course. The cushions aren’t plumped, the soft olive throw is stretched across the entire bed, not just the foot of it. These tiny details remind me that I wasn’t the last person to sleep in this bed – rather another woman and her husband.

I set down my case, then wander round my room, eyes scanning the clean surfaces. I slide open my wardrobe door; my clothes are still hanging in one portion of the wardrobe just as I’d left them, the rest of the rail clear for the other couple’s clothes. I move to my bedside drawer and pull it open. Empty, as I’d left it – oh, except for a small pot of men’s hair wax pushed right to the back. I twist off the lid and, seeing it is almost empty, drop it into the bin.

Taking out my washbag, I move to the large free-standing mirror at the foot of my bed, where I dab cleanser onto a cotton pad and sweep it gently around my face. I’ve picked up a little colour in France, and my hair has been lightened by the sun to a warm caramel shade.

As I lean in, that’s when I notice them: fingerprints. Larger than mine. I look closer: a hand has been pressed flat to the mirror, the smear of a stranger’s skin marking the glass.

Standing here with the empty room reflected behind me, an unsettling feeling creeps over my skin. Someone else has been in this room. Been in my house. The woman who’d rented it – Joanna – must have stood where I am, her image caught in the mirror. It feels as if this stranger’s gaze is still here, watching.

As I step back, a hot pain bursts into my heel.

I snatch up my foot, reaching out for the wall for balance. There is a deep puncture in the very centre of my heel, a bead of blood springing to the surface. What the hell have I stood on? I crouch down, searching the carpet, running my palms across it until they meet the waspish scratch of something.

A shard of glass, knife-sharp, is lodged deep in the plush carpet. I grip it between my fingers and carefully pull it out. The downlights illuminate a beautiful blue icicle, something vaguely familiar in the glitter of the glass.

Has something of mine been broken? I can’t think of anything in my bedroom that this piece could’ve come from. I keep the surfaces of my bedside table clear, except for a tripod lamp and a jug for flowers. My bottles of perfume have been packed away with the other breakables and valuables, which I’d locked in my writing room. It’s unsettling to not be able to place this lethal dagger of glass.

I wrap it in a tissue and, as I drop it into the bin, I glance down at the cream carpet and see it is marked with the crimson blush of my blood.

Previously

Oak, jasmine and something citrus – those are the smells that greet me as I step inside. There is a clean, fresh quality to the air that is different to my house: it is dry, free of cooking smells, or that earthy dampness that comes from washing dried on radiators.

I can’t help myself. ‘Hello?’

There is, of course, no reply. I smile. The quiet is beautiful, softened by the distant sound of the sea.

My black holdall looks incongruous on the solid oak floor. I kick off my shoes and leave them discarded. Yours, I see, are placed neatly beneath the oak settle.

I walk through the entrance hall, which leads straight into the spacious kitchen. The walls are a warm shade of white; I think the paint has been chosen with light-diffusing particles so that it feels as if the walls are breathing air into the room. The splashes of colour – chalky pastel shades – come from the painted wooden cabinets, the well-chosen artwork, the pottery carefully displayed.

The style is graceful, calming. It’s as if a handful of sea-bleached pebbles have been gathered and used as the basis for the palette. The modern, sleek lines of handle-less cabinets and a granite work surface have been married with a beautiful old farmhouse table, the wood ring-marked and age-worn. A long bench seat is set against the wall, strewn with hessian cushions. It’s a table for a family, or for dinner parties. Not a table for one.

I smile to see that the high chair, as requested, is placed at the end of this table, although it won’t be used, of course. On the kitchen counter there is a small bunch of wildflowers in an old honey pot, tied with brown string. Leaning against it is a handwritten card addressed to Joanna and family.

A thoughtful touch.

I pick up the card, tracing a finger across the elegant handwriting, but I don’t open it.

Setting it back down, I move past an aged dresser painted duck-egg blue, where earthenware mugs hang from neat iron hooks. Seagrass-speckled pots are stacked artfully between mason jars containing nuts, pulses and attractive spirals and ribbons of pasta. I slide open the dresser drawer and, as I reach into it, I experience the sharp sensation that someone is going to snap the drawer shut on my fingers, a child caught snooping.

I feel like a trespasser. Yet, in my pocket, I’m aware of the small but solid presence of the front door key resting against the top of my thigh.

I am no trespasser, I remind myself. You let me in.

3

Elle

‘If you’re going to throw a ticking bomb into the story, light the fuse at the beginning, and let us hear it tick.’

Author Elle Fielding

In the charcoal-coated dark of three a.m., I am awake. The cut to my heel throbs; my pulse seems to tick there.

Over the years I’ve tried a wealth of tips and tricks to soften insomnia’s grip: a soak in a lavender-scented bath; listening to an audio book; blackout blinds; a warm, milky drink before bed; that sodding meditation app that I’d thought was the key but eventually stopped working, too; no screen time; no sugar after dinner; sleeping pills; homeopathic remedies; acupuncture. Everything. I’ve tried everything.

People don’t understand that it’s not falling asleep that’s the problem. It’s staying asleep.

If only there was just a switch for my mind, some way of turning it off, or at least turning down the volume; instead, as the night draws deeper, worries begin to stir, stretch, wake. Harmless, innocuous happenings take on a different shape – the shadows they cast, stretching.

The chef I used to work with when I was waitressing in a pub called them the heebie-jeebies.

‘Don’t trust any thoughts you have between two a.m. and five a.m. It’s like listening to your drunk self.’

Reminding myself of this advice doesn’t settle me tonight. I inhale and exhale slowly, following the path of my breath.

But I can still feel it: the ice-sharp point of that shard of glass as it pierced my skin.

*

I lean against the kitchen counter, listening to the low gurgle of the coffee machine as the water begins to heat. What would I do without coffee? I finally stumbled into a deep, dreamless sleep at around five a.m., but now I feel thick-headed, disjointed.

Beyond the window, mellow white clouds blanket the sky, thin swatches of blue glimpsed beyond. A kayaker is powering across the bay, the paddle lifting and dipping with pleasing fluidity.

On the shoreline there’s a lone birdwatcher, collar pulled to their chin. They are standing with their head tilted back, binoculars raised towards the cliff. There’s a stillness about them that I admire – lovely to be so enraptured by bird life that you’d want to dedicate hours of your day to simply observing it.

I follow the direction of the birdwatcher’s gaze to see if I can locate what they’ve spotted.

As I follow the angle of their binoculars, unease trickles down my spine. Their gaze isn’t focused on the cliff. It is set higher.

They are watching my house.

A memory, match-bright, flashes through my thoughts: his slow smile; the dark, knowing eyes that followed me, hawk-like with exacting focus; the pleasure in his voice as he said my name.

I extinguish the memory with a blink, yet feel the shiver it leaves behind.

Course they’re not watching the house, I tell myself. The binoculars must be trained on a bird; sand martins nest nearby, and there are rare but occasional sightings of a pair of peregrine falcons.

The stranger’s hair is covered by a hat pulled low to their ears, but something about the way they stand, the straightness of their posture, a narrowness of shoulders, makes me wonder if it’s a woman.

The stranger seems to become aware of me at the window, as they lower their binoculars and, just for a moment, our eyes meet. There is a beat of time – no more than a matter of seconds – when we are looking at one another. Then the stranger turns, moves on.

Sliding my mobile towards me, I see my editor’s name flashing.

I adjust my face into a smile. ‘Jane. Hi.’

We exchange niceties about my writing retreat and Jane’s visit to the Frankfurt Book Fair, and then Jane takes a breath, signalling the inevitable slide from small talk to business.

‘So, I just wanted to touch base and check we’re on track for next month’s deadline.’

My shoulders stiffen. The book is already months overdue. I’ve cited house renovations and marriage difficulties – and in fairness to Jane, she has been understanding, extending the deadline twice. Her patience, however, is starting to thin – and I can’t blame her. A final deadline has been set for the tenth of December and, if the new novel isn’t handed in, I’ll be in breach of contract.

During the writing retreat, I’d made time to think about the novel I am writing – or more accurately, am not writing. I’ve been switching between ideas for months, with so many false starts that I’ve lost my confidence, my instincts. The ideas aren’t big enough, aren’t exciting enough to carry a reader through. If I’m not inspired or excited by a story – why should readers be?

Second novel syndrome, David, one of the other tutors on the creative writing retreat, had called it.

‘If you have a big success on your hands,’ he’d said, while spreading sun-warmed brie onto a cracker, ‘then it’s like all those generous words of praise from reviewers and readers are stacked up in front of you. Your debut was an international bestseller – it scooped every bloody award going. Readers are desperate for whatever’s coming next. It’s hardly surprising that every time you attempt to write, the expectation towers over the page. You’re writing in a book shadow.’

Book shadow, I’d thought afterwards as I’d lain in the cool of my room, red wine making my head swirl, the shutters thrown open so I could catch the sound of birdsong beyond the window.

‘It’s coming on well,’ I say to Jane now, the tightness between my shoulder blades spreading down my spine.

‘We’re all so excited to read it,’ Jane says brightly. ‘Would you be happy to send across what you’ve written so I can start to get the flavour of it? I’m eager to brief the designers for our cover development.’

I picture the plain black notebook, a tangle of words jostled into paragraphs, sentences scribbled out, entire pages slashed with a single pencil line.

‘Actually, I’m in the middle of revising a plot thread. If you don’t mind, let’s stick to the tenth of December.’

Jane accepts – what else can she say? We talk a little about an upcoming interview my publicist is in the process of securing with Red magazine, the date yet to be confirmed. Before Jane signs off, she says, ‘I’m looking forward to your Facebook Live debut shortly.’

I glance at my watch. Just under an hour to go.

Before I left for France, Jane talked me into doing a series of live videos, telling me it would be a good way to connect with readers and build up pre-publication buzz.

When I said I had no idea what I’d talk about, she sounded genuinely surprised.

‘Elle, you’re a confident, eloquent young woman. You’ll be fine. Readers just want to know more about you – where your ideas come from, how you write. That sort of thing. Keep it informal – maybe start each week with a writing tip, you know, like “Things I’ve learned as an author”. Then answer any questions.’

I couldn’t think of a good enough reason to say no.

Now she says to me, ‘We’ve been pushing it across our social media channels, so we’re hoping you’ll have several thousand people tuning in live. We’ll all be cheering you on at the office.’

All those people watching me. Asking me questions. Live. No room for mistakes. No possibility to edit. Nowhere to hide. Just me – Elle Fielding, author – in my writing room.

I put down the phone, aware that I’m sweating.

The air cools as I climb the stairs to the top of the house.

I kept my writing room locked during the rental; I needed somewhere to store my valuables – but also, I didn’t like the idea of a stranger sitting at my desk. Odd of me, I know.

I slip the key from my pocket and spend a moment fighting the lock, turning it back and forth until I hear the bolt release. I push the door wide open.

Light fills the space, the shimmering scales of the sea pouring through the glass wall, streaming over the stripped wooden floorboards and across white walls. When I’d designed this room, I’d wanted to create a space where my imagination could travel beyond a desk, beyond a computer screen, beyond the walls of the house – for it to sail off towards the endless promise of the horizon.

I’ve kept everything purposefully pared back and unadorned. The only pieces of furniture are an aged oak desk, a simple bookshelf constructed from reclaimed scaffold planks, which display a collection of my favourite novels, and a ceramic oil burner. In the far corner of the room, there’s a wingback chair turned to the view, and beside it an oak trunk that houses notebooks, photographs and diaries.

I cross the room, surprised to notice the fresh scent of salt in the air. I thought it would be stuffy up here after keeping the room locked for a fortnight.

Then I see it: the small window at the edge of the glass wall is open. I’m surprised – I always double-check the doors and windows. I must have somehow overlooked it. I know no one could have accessed the room during the Airbnb as I left it locked and took the only key with me.

I let the thought go as I settle myself at my desk. I love this desk. I came across it at Kempton Market four years ago. At the time, Flynn and I were living in a rented flat in Bristol, and I’d just begun working on my first novel – carving out slices of time to write in lunch breaks, or after I returned from a shift. I kept my ambition secret – except from Flynn – as somehow the dream felt too new, too fragile to be spoken about, as if a misplaced remark could have the power to damage it. As we’d left Kempton Market, I’d told Flynn, ‘If I ever get a book deal, the first thing I’m going to do is buy a writing desk.’

Unbeknown to me, Flynn called the seller and arranged for the old desk to be delivered to his mother’s garage. On the weekends when he visited his mother, he spent hours restoring the desk, treating it for woodworm, sanding it right back, working into the grooves of the ornate legs, removing the layers of varnish that had been reapplied over the years. He’d changed the handles, waxed the runners, and sealed the cracks.

A year later, when my novel was finally finished, I printed out six copies ready to send to prospective literary agents. That’s when Flynn took me to see the desk.

‘I was going to wait till you got your first publishing contract,’ he said, as we’d stood in his mother’s garage, the smell of turpentine spiking the air, ‘but I think this day is more important. You finished your book, Elle. Whether this one’s published, or whether it’s the next one, or the one after that – you’re a writer now.’

The timer on my phone beeps.

One minute to go.

My stomach turns over with nerves. Several thousand people tuning in live.

I sit up straighter, pull my shoulders back. I know what I need to do. What everyone is expecting from me.

I reset my focus, drawing my gaze to my laptop. My own face glares back at me on screen using the laptop’s camera. Perhaps it’s just the tilt of the screen, or the way the light pours into the room, but for a moment, I don’t recognise myself.