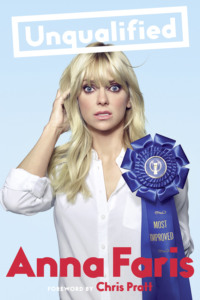

Unqualified

After Chad, I went from one relationship to the next. Because I was constantly trying to make a bad thing work, I was a serial monogamist, and I’m embarrassed to admit that it used to take meeting another person for me to realize that Oh, this relationship might not be working. I’ve had my share of romantic troubles, and what has continually provided me with comfort is the knowledge that millions of people out there have been through what I’ve been through. Heartbreak and rejection are communal. Love is life’s greatest mystery and wildest adventure.

God, that’s so fucking corny.

I started a relationship podcast because, to me, giving advice and hearing other people’s stories is better than therapy. Not that I’m in therapy. I probably should be, but I find it too frustrating to not know anything about the person I’m talking to. The two times I visited a therapist I found myself asking about them—“I don’t see a ring on your finger. Are you divorced? That must have been hard. Tell me everything!”—and they politely but firmly deflect and steer the conversation back to me. Then I try to get them to tell me about their other patients, which they seem to think is against some sort of rule.

Hearing other people’s problems is, in its own weird way, comforting. It’s a relief to me that so many of the trials I’ve had, other people have, too. And while I may be unqualified, I’m not uninterested. I care and I listen and maybe I don’t always give the best advice, but I really do try. I dig a lot. I have no problem asking anyone anything. I’ll try to curb my own obnoxiousness by saying, “I know this is personal … ,” but then I go in for the kill: “How did you and your husband meet?” or “Oh, you’re online dating? How does that work? Ever get catfished?” Some people really respond to it. Other people really, really don’t.

I know what you’re thinking: That all sounds great for a podcast, where that girl who looks like Mena Suvari can take callers and have a conversation, but what’s going on with this book? Well, apparently, after two years of hearing other people’s stories, I’ve learned a few things. About myself, about dating, and about the commonality of lust and heartbreak and desire and rejection and giddiness. I’ve been reminded that whether you’re in LA or Atlanta or Dubuque, your pride will be wounded after a breakup, you’ll struggle to tell a friend when you can’t stand her boyfriend, and when you’re truly happy, you’ll know it. I’ve learned that there are some universal truths: If your closest friends stop showing up to your barbecues, you’re probably in a bad relationship. And if you opt for kindness over teasing, you’re probably in a good one.

I’ve come a long way since that night in 1987 when I so cavalierly told a mom of two to up and leave her husband. I don’t get a rush from encouraging breakups anymore. These days I’m more interested in bringing people together. In fact, just recently, a friend of mine was going through a bad breakup, and thank God I was there. She and her ex had had this incredibly passionate, whirlwind courtship—within two months of meeting they were planning the wedding. But then they broke up, which was not entirely surprising in a situation like that. Shortly afterward, my friend came over to my house and was so incredibly upset. The more I thought about it, the more I knew I had to intervene. There was still a lot of love there, I just knew it, so I asked my friend for her phone. “What are you going to say?” she asked.

Didn’t she trust me?

“Just let me have your phone,” I said. My text was simple: “Hey, it’s Anna. I don’t know what you’re doing right now but will you come over?” He did, and they had a beautiful, romantic night. I was so proud of myself! I got them back together and all would be fine and, like I said, I knew there was love there. I knew it.

He ended up leaving two days later and she was devastated and I think maybe a little annoyed at me. So, yeah. It backfired.

Still, points for trying?

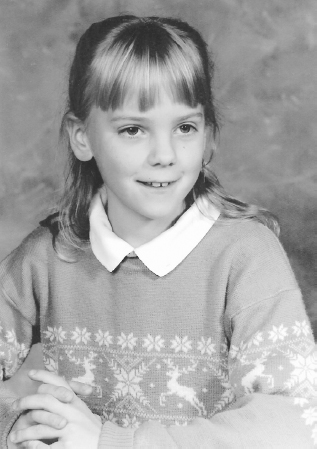

In this book, you’ll find stories of my relationships, both the disastrous and the heartwarming. You’ll meet childhood Anna (pronounced Ah-na, rhymes with Donna, even though everyone gets it wrong and I never correct them), armed with flannel shirts and menacing headgear, and adult Anna, with more flannel shirts but much better teeth. You’ll get some advice, a few lists, and some childhood photos (I’m the short one).

Read. Have fun. And please purchase the sequel: I Have No Idea What the Fuck I’m Talking About: The Motherhood Book.

The Fastest Boy in the Third Grade

Remember when you first spotted him sprinting across the playground, schooling the other boys in a heated game of tag? Or the moment you noticed him at his desk, brown spiky hair sticking up in all the right places?

He was the first boy to make you crave the male gaze; he made you wonder what it would be like to have a boyfriend; he inspired you to start a diary.

You’ve been there, dear reader, haven’t you?

For me, that boy was Jason Sprott.

Jason Sprott was the fastest boy in the third grade. You know how in elementary school everyone is known by their first and last name? Jason Sprott was always, and only, Jason Sprott.

He had the most adorable freckles and a great smile and spiky brown hair that I couldn’t resist. We were in the same class, but we were nowhere near each other on the social hierarchy. Jason was a sweet, confident kid who totally knew his own charm—the top of the social food chain. I had more of a C-level social status. It started when I moved to Edmonds, Washington—a suburb thirty minutes outside Seattle—when I was six. I went from a blue-collar community in Baltimore where everyone was friends and had barbecues and family get-togethers to this faux-upper-class neighborhood that felt incredibly superficial. I know that’s counter to the perception of Seattle, but my brother and I both felt like it was different in Edmonds. When I say I’m from Seattle it always feels misleading—moving to Edmonds felt a little bit like moving to Anywhere, USA. It did not live up to the Seattle stereotype.

We arrived in Edmonds in the spring, and on my first day of first grade, my mom put me in a really dramatic sheepskin coat. When she buttoned me up that morning, all I could think was, I cannot wear this to my first day of school. I was six, and even then I knew this was not good. A six-year-old in sheepskin does not have the makings of social success.

Sure enough, the other kids completely mocked me. It stung, but it also planted the seed for a weird-clothing rebellion that emerged in middle school. During those years, I wore the most hideous sweater, Charlie Brown but in reverse: it had more of the dark color than the light, and it was totally disgusting, but I embraced it for its ugliness. That sweater was my early fuck-you to the mean girls and the popular kids and the mundane existence I thought Edmonds offered. Then, in ninth grade, I wore a Christmas tree skirt like a cape, which of course got me lots of suitors.

Do I look stoned in fifth grade?

Looking back over the years, I’ve always gotten a lot of strength from being the underdog, or what felt at the time like the underdog. Maybe that started with Jason Sprott. He had a twin brother, David, but unfortunately for David they weren’t identical. All the girls had a crush on Jason.

We were in the same class. Jason sat in front, as did his girlfriend, Michelle. I preferred to sit in the back and stare at my crush and his little hair spikes. I recently found the diary I kept in third grade, with pages of scribbles about Jason Sprott. I love Jason Sprott. I hate Jason Sprott. I love Jason Sprott. He smiled at me today. We were assigned our Greek gods and he was Eros, the god of love, and I was the unsexy Hera but he shot me with his arrow.

One day, I was in the cafeteria and Jason was behind me in the lunch line. After buying my lunch, I spent the thirty-five cents I had left over on the ice milk dessert. Ice milk was imitation ice cream before frozen yogurt was a thing. I guess it was better for you, but to us third graders, it was all the same. At least, it was appealing enough to get Jason’s attention.

“Man, I wish I could get an ice cream,” I heard him say behind me.

“I’ll buy you one!” I offered eagerly.

This transaction—my using my extra change to buy Jason Sprott ice cream, Jason Sprott letting me buy him ice cream—went on for a couple of weeks, until finally he said, “I’ll go out with you, but you’ve got to know that I’m also going out with Michelle.” He was a real class act: he told me about Michelle and was honest that he wanted us both. Sounds good, I thought. I’ll take what I can get!

Michelle was supercool and popular and had a fountain in her house, which was a big deal. The next year, in fourth grade, I invited her over to my place, and she actually accepted and came to my home. That was a shock. My mom had just bought an inflatable boat from Costco. She blew it up, and Michelle and I put it on my bed and played white-water rafting adventure. We were laughing and really getting into it, riding the make-believe waves and capsizing onto the bed. I’d never seen that side of her. I thought we were having so much fun. A week later, the popular girls all made fun of me because I liked to play boat.

But back in third grade, when my romance with Jason was blossoming, Michelle and I didn’t have much of a relationship. Shortly after I bought Jason that first ice cream, she came up to me and said, “I know you’re going out with Jason too, and I just want you to know I’m cool with it.” She walked away before I could even respond.

Jason and I didn’t speak to each other during our courtship. I mostly saw him during recess, when everyone played tag, and of course he never got caught, since he was such a fast runner. It was the hottest thing about him. But even at recess we were G-rated. There was a big moment on the playground when Amy Gray and Sean Bryant were going to have their first kiss and everyone crowded around them and they exchanged the tiniest little peck. That was a pretty huge event—I remember it more than any actual education I got in third grade. The non-kiss was a monumental moment in my social education. But with Jason and me, there was no peck. There was just the lunchroom, where I continued to bribe him daily with ice milk. I knew, on some level, that I was buying this guy. I wasn’t getting his attention on my own merit. Even at eight years old, I was a realist. So while it was exciting that he went out with me, it felt like what I imagine it feels like when you win the lottery but you only win, like, $5,000.

Still, I envisioned myself as the third-grade Seattle equivalent of a scrappy Boston fighter. All odds were against me—I shouldn’t say that, because I’m a blond white American person—but when it came to Anna versus Michelle, there was no comparison in the eyes of the elementary schoolers. I was the short girl who wore a sheepskin coat to her first day of school; Michelle had a fountain in her house. That pretty much said it all, and yet there I was, sharing Jason with her. For the first time, when it came to social status, I was A-list-adjacent.

Jason dumped me a couple of weeks later. He confronted me at recess and said, “I don’t think we should go out anymore, I’m just going out with Michelle.” It was a stab to the heart. I was devastated. I had nothing to give him but my thirty-five cents and he didn’t even want that anymore. Maybe Michelle got in his head. She was supersassy and played her cards right. I, on the other hand, was a true sugar mama.

So I did what any heartbroken eight-year-old would do: I went home, grabbed an orange from the fridge, wrote Jason’s name on the peel in black marker, and threw it off the deck into the forest outside my house. When I was a kid, I wanted to live in the Yukon, so I spent a lot of time in that backyard forest relishing my loneliness. I was dying to live a more dramatic life than Edmonds offered, even then. And this weird ritual, which I deemed “the orange ceremony,” seemed like a start. I don’t know where I came up with it. I certainly didn’t read a book that said to pick up an orange and write a boy’s name on it in order to get over him, but I ended up doing it with a few different love interests. I must have thought it was profoundly symbolic: that by casting this fruit into the abyss, I would somehow rid myself of the hold these emotions had on me. Even at that age, it’s so surprising the intensity of feelings you can have for somebody. I felt the need to be liked and the need to be popular, but I was tortured by that neediness, because I was also proud and wanted desperately to be confident and independent. I thought the ritual would help. I remember throwing the orange out there and thinking, Now I am complete! Now I am over Jason Sprott!

It didn’t work; I was not released. The next day I went to school and saw Jason, and saw Michelle, and was just as devastated.

That episode began my long and complicated journey with the idea of closure. Basically, I don’t believe in it. I believe in the concept; I get why people crave it, and I understand why I, even in third grade, sought it from the orange ceremony. It’s frustrating to feel so powerless against your own feelings. But as an adult, I’ve learned that closure is unobtainable. I think it happens at death, maybe. But remembering the pain is a good thing, because all those experiences that you can’t close the door on make you a more empathetic person, and that should be embraced.

I have a pattern—it takes meeting a new guy to help me get over the old one. In the case of Jason Sprott, it was another Jason. He was the newspaper boy, supercute and a little bit brooding. I left him sodas outside my house every day so he could have a drink while he was delivering papers. I was totally into bribing these guys. What can I give him out of my fridge that will get his attention? I think there are five pages in my diary that read: I am so over Jason Sprott, I am totally into Jason Berry. He is soooooooooooooo hot and such a mystery! But one day he didn’t take the soda, and I think that was his way of saying, “No more, you sad girl.”

Despite our tragic end, Jason Sprott will always be my first crush. We ended up going to different high schools, so I lost track of him after eighth grade. He has probably changed a lot in the past thirty years. But to me he’ll forever be Jason Sprott: lover of running, subsidized ice cream, and spiky bangs.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.

Вы ознакомились с фрагментом книги.

Для бесплатного чтения открыта только часть текста.

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера:

Всего 10 форматов