Ad Infinitum: A Biography of Latin

In the first century, Spain was preeminent. From Corduba (Cordova) came L. Annaeus Seneca,* the tragedian and moralist (son of an equally literary father, who had concentrated on rhetorical declamations), and his nephew M. Annaeus Lucanus, the epic poet of the Roman civil war; from Bilbilis (Calatayud) came M. Valerius Martialis, writer of epigrammatic verse. L. Iunius Moderatus Columella from Gades (Cadiz) wrote the classic text on farming; and M. Fabius Quintilianus from Calagurris (Calahorra) was an orator, but even more famous as the classic authority on rhetorical theory.†

In the second century, the historian P. Cornelius Tacitus and the theorist of aqueducts and military strategy Sex. Iulius Frontinus came from southern Gaul. But the real competitor was Africa: C. Suetonius Tranquillus the biographer, M. Cornelius Fronto the orator, C. Sulpicius Apollinaris the grammarian, all came from there. Africa’s cultural repute at the time was captured in a quip of Juvenal’s: NVTRICVLA CAVSIDICORVM AFRICA ‘Africa, that amah of advocates, suckler of solicitors’.26 Meanwhile Greeks, and other residents of the eastern provinces, are absent from this roll, as they continued to write in Greek. Some famous literary westerners (notably the sophist Favorinus, hailing from Arelate (Arles) in southern Gaul) even chose to be Greeks rather than Romans.

All these luminaries had felt they needed to travel to Rome to take part in the language’s cultural life at the highest level. This changed in the later second century. Apuleius, after studying in Greece and Italy, returned to Africa to work and write his bawdy but devout novel Metamorphoses (better known as “The Golden Ass”). Thereafter it seemed no longer necessary to establish oneself at Rome to make a literary or philosophical reputation. The poet Nemesianus (around 250–300), and the Christian writers Tertullian (around 160–240), Lactantius (around 240–320), and Augustine (354–430) all stayed in North Africa; others, such as the Bible translator Jerome from Pannonia (347–420) and the historian Orosius (early fifth century) from Spain, were happy to travel and work (in Latin) in different parts of the Empire.* The Empire was the basis for the creation of RESPVBLICA LITTERARIA, a Republic of (Latin) Letters, which was to be an aspect of western Europe for the next millennium and beyond, almost unaffected by political and economic collapse.

The army too, like the process of literary education, provided a motive for the spread of Latin within the Empire, but one that affected a different, and very much more numerous, class of people. We are best informed about the top flight of military men, drawn from ever wider circles: the most successful could ultimately even become emperor. Already in the last days of the Republic (to 44 BC) it had been possible for provincial Italian lads to ascend to high command: T. Labienus, Caesar’s principal aide in Gaul, and P. Ventidius Bassus, who campaigned successfully on behalf of Mark Antony in Parthia, both seem to have come from modest backgrounds in Picenum.

A century later, after the Julio-Claudian and Flavian dynasties had run out of heirs, the Empire was forced to fall back on outstanding soldiers; and it became clear that such distinction was no longer restricted to men from the traditional elite in Rome and Italy. Two emperors from Spain (Trajan in 98, Hadrian in 117) were succeeded by one from Gaul (Antoninus Pius in 138). After a turbulent interregnum caused by an attempt to reinstate the dynastic principle, military candidates for emperor again started emerging from the provinces, and more and more distant ones: Africa (Septimius Severus in 193, Macrinus in 217), Syria (Philip 244), Thrace (Maximinus 235), Pannonia (Decius 249), Moesia (Aemilianus 253). Aurelian, acceding in 270, even came from outside the Empire, in the lower Danube region.

The Latin language itself became a sort of repository of the languages of the peoples the Romans had subdued and brought into their great coalition. Many of the words are simple borrowings, but many more are harder to place, since they seem to be portmanteaux: Latin words clearly, but somehow dressed to look foreign. LYMPHA with its Y and its PH looks a clear borrowing from Greek, but it isn’t. It is just a grandiose word for ‘water’, redolent of nymphs, limpid pools, and deliquescence. Sometimes it is matched with nymphs, as if it were the word for another kind of water fairy; sometimes it becomes the name of a goddess in her own right, as when Varro invokes her (along with the equally bogus ‘Good Outcome’) at the beginning of his treatise on agriculture.27 It went on to be a pseudo-explanation for all kinds of frenzy, of the sort that the wild spirits of wood and water will send down on mortals: LYMPHATICVS was much the same as LVNATICVS.

Home provinces of the Roman emperors. From the first to the third centuries AD, emperors were chosen from ever farther afield.

ARRA is another such word, meaning a bond or surety, but this time shortened from a word taken from a Semitic language, probably Punic, the language of financial transactions par excellence. Pliny the Elder jokes that a doctor’s fee is MORTIS ARRAM, a down payment on death.28 Its original form ARRHABON represents the Semitic ‘erabōn, but in ARRA it has been shortened to be like Latin ĀRA, an altar—but a more Roman-feeling security: as when Ovid says that a friend of his is “the only altar that he has found for his fortunes.”29

To add a third cultural mixer, consider the word CARRICVM, unknown to Latin literature, but evidently universal in spoken Latin, since echoes of it are found in every modern Romance language (French charge, Spanish cargo, Rumanian cârcă, Catalan carreg, Italian carico…) as well as English carry. At the start, it evidently meant a wagonload, such as a CARRVS (a word borrowed from Gaulish, to mean four-wheeled cart) could hold. CARRVS has had a major career of its own (e.g., car, chariot, career), but CARRICVM is another example of a word borrowed into Latin that there found a new and extended life, first as the replacement for the ancient Latin word ONVS ‘burden, load’, later with a rich metaphorical life, ranging over duties, pick-a-back rides (in Romanian at least), accusations, attacks, and (much later) ammunition for firearms, and then explosives generally. Gaulish may have been the language of choice for words for wheeled vehicles, but Latin gave an opportunity for transfusion into Europe’s future world-mind.

Languages create worlds to live in, not just in the minds of their speakers, but in their lives, and their descendants’ lives, where those ideas become real. The world that Latin created is today called Europe. And as Latin formed Europe, it also inspired the Americas. Latin has in fact been the constant in the cultural history of the West, extending over two millennia. In a way, it has been too central to be noticed: like the air Europe breathed, it has pervaded everything.

It was the Empire that gave Latin its overarching status. But, like the Roman arches put up with the support of a wooden scaffold, the language was to prove far more enduring than its creator. As the common language of Europe, spoken and written unchanged by courtiers, clerics, and international merchants, its active use lasted three times as long as Rome’s dominion. Even now, its use echoes on in the law codes of half the world, in the terminologies of biology and medicine, and until forty years ago in the liturgy of the Catholic Church, the most populous form of Christianity on earth. And through these last fifteen hundred years, Europe has remained a single arena, largely independent of outsiders, even as parts of it have sought to dominate the rest of the world.

Yet after the collapse of Rome’s empire, Europe itself was never again to be organized as a single state. The Latin language, never forgotten, was left as a tantalizing symbol of Europe’s lost unity. “Once upon a time the whole world spoke Latin.” This mythical sense remained behind Europe, and its proud civilization. And so, more than Christianity, freedom, or the rule of law, it has in practice been the sense of a once-shared language, a language of great antiquity but straightforward clarity, that has bound Europe together.

CHAPTER 2

Fons et origo—Latin’s Kin

MAIORES NOSTRI…VIRVM BONVM CVM LAVDABANT, ITA LAVDABANT, BONVM AGRICOLAM BONVMQVE COLONVM. AMPLISSIME LAVDARI EXISTIMABATVR, QVI ITA LAVDABATVR.

Our ancestors … when they singled out a good man for praise, used these words: “a good farmer and a good settler.” Someone so praised was thought to have received the highest esteem.

Cato, On the Country Life1

LATIN OWES ITS NAME to its home region of Latium in west-central Italy, the southern half of modern Lazio. With hindsight, it certainly looks a good starting point for a future Italian, and then Mediterranean, power. Its position is central in Italy, and it controls the ford on the river Tiber (modern Tevere), which is the main divider of Italy’s western coastal plains. Italy, in turn, is central within the northern sector of the Mediterranean, equidistant from Spain in the west and Asia Minor (modern Turkey) in the east.

The first question that naturally arises is why the language is not known as “Roman,” for the power that spread the language far and wide was not Latium, but the city-state of Rome, and the result was the Roman, not the Latin, Empire. But the Romans’ influence was usually decisive, even with outsiders, in setting the names of their institutions; and the Romans always referred to their language as lingua Latīna, or sermō Latīnus. It shows that the language is older, and its area, originally at least, wider than the Roman state.

Languages of ancient Italy. Until the third century BC, Latin was just one among many Italic languages.

Looking as far back as we can to the origins of Latin, we do not have the convenience (as we do for English) of being able to give it a place and a period. But it is discernibly an Indo-European language, a member of a highly diverse family of related languages whose borders were set, before recorded history, between Bengal and Donegal (and indeed between Iberia and the edge of Siberia). Its speakers will have reached Latium along with the forerunners of most of the other language communities that largely surrounded Latin when we read their first traces in the written record. They are called Italic languages and included Faliscan, Umbrian, and Venetic to the north, Oscan to the south.* Sadly, there is no agreement on when these languages would have come to Italy (sometime between the sixth and the second millennia BC, but all as a group, or in separate events?), on what allowed their speakers to spread (prowess at farming? Copper, Bronze, or Iron Age weaponry?), or even on what their route would have been (over the sea from the Balkans? down the Adriatic or the Tyrrhenian coasts?). We can only say where in the Italian peninsula the Italic languages ended up, and what sort of languages they were.

As to where in Italy they settled, it is clear that there were two major groups or subfamilies: Latin-Faliscan-Venetic settled the north, whereas Oscan and the rest, usually known as the Sabellian languages, occupied most of the south of Italy. The main exception to this pattern is Umbrian, a dialect which is more similar to Oscan than northern Italic; so its position in north-central Italy suggests that the Umbrians migrated later from the south up into the Apennines. It is also significant that the very similar Latin and Faliscan—a dialect best known for its drinker’s motto FOIED VINO PIPAFO CRA CAREFO “Today I shall drink wine; tomorrow I shall go without.”2—were separated from their cousin Venetic by a large, and totally unrelated, Etruscan-speaking population. The geography suggests that the Etruscans moved in from the west, splitting the two wings of northern Italic apart.

The Italic languages were not mutually intelligible, at least not across their full range. An idea of how different they could be may be gained from looking at some very short texts in the two best known and farthest flung (Venetic and Oscan) with a word-for-word translation into Latin. (For comprehensibility, none of the languages is shown in its actual alphabet.)

First a Venetic inscription on a bronze nail, found at Este:

mego zontasto sainatei reitiai egeotora aimoi ke louzerobos [Venetic]

me dōnāvit sanātricī reitiae egetora aemō līberīsque [Latin]

i.e., word for word in English:

“me gave to-healer to-Reitia Egetora for Aemus and children”

or more clearly:

“Egetora gave me to Reitia the healer for Aemus and his children.”

And then a clause of a Roman magistrate’s arbitration (183 BC) between Nola and Avellino, written on a boundary stone:

avt púst feihúís pús fisnam amfret, eíseí tereí nep abellanús nep nuvlanús pídum tríbarakattins [Oscan]*

autem pōst murōs quī fānum ambiunt, in eā terrā neque avellānī neque nōlānī quicquam aedificāverint [Latin]

i.e., word for word in English:

“but behind walls which temple they-surround, on that land neither Avellani nor Nolani anything they-shall-have-built”

or more clearly:

“but behind the walls which surround the temple, on that land neither the Avellani nor the Nolani may build anything.”

Nevertheless, there are striking similarities among them, and features, from the most specific to the most general, that set Italic languages apart from the other Indo-European languages.

First of all, a distinctive sound in Italic is the consonant f. It is extremely common, cropping up mostly in words where the Indo-European parent language had once had either bh or dh. In Latin, the sound is mostly restricted to the beginning of words, but in Oscan and Umbrian it often occurs too in the middle: Latin fūmus, facit, forēs, fingit; Oscan feihús, mefiú; Umbrian rufru—meaning ‘smoke, does, doors, makes’; ‘walls, middle’; ‘red’.*

With respect to meanings, the verb form ‘I am’ is sum or esom, with a vowel (o or u) in the middle and none at the end; there is no sign of such a vowel in Greek eimí, Sanskrit asmi, Gothic im, Hittite ešmi. There are also some distinctive nuances of words in the Italic vocabulary (asterisks show that forms are historical reconstructions): the common Indo-European root *deikmeans ‘say’ here (Latin dīcere, Oscan deíkum), not ‘show’ as it does in the other languages (Greek deíknumi, Sanskrit diśati, English token); also, the root *dhē- means ‘do’ or ‘make’ (Latin facere, Oscan fakiiad, Umbrian façia, Venetic vhagsto ‘made’) and not ‘put’ as it does in the other languages (Greek -thēke, Sanskrit -dhā-).

The pattern of verb forms is simplified and regularized from Indo-European in a distinctive way. As every schoolboy once knew, Latin had four different classes of verbs, each with slightly different endings, known as conjugations. The different sets of endings corresponded to the vowel that closes the stem and preceded the endings (as amā- ‘love’, monē- ‘warn’, regĭ- ‘rule’, audī-‘hear’). This vowel then largely determined the precise forms of all the verb’s endings, 106 choices in all.† Something similar is seen in Oscan and Venetic verbs. This is complex by comparison with English, but is in fact rather simpler than the fuller, differently organized systems seen in such distantly related languages as Greek, Sanskrit, or Gothic, where one can find more persons (dual as well as singular and plural), an extra tense (aorist), voice (middle), and moods (optative, benedictive).

The nouns, on the other hand, followed five patterns (declensions), choosing a set of endings on the basis of their stem vowel (-a, -o, none, or -i, -u, -e): the endings marked whether a noun was singular or plural (here too, in Italic languages, dual was not an option), and which case it was in, i.e., what its function was in the sentence; the cases were nominative (for subject), accusative (for object), genitive (for a noun dependent on another noun), dative (for a recipient), ablative (for a source), locative (for a place), and vocative (for an addressee), though the last two had become marginal in Latin. Hence analogously to a Latin noun like hortus ‘garden’, which had a pattern of endings

Sing. N. hortus, Ac. hortum, G. hortī, D. hortō, Ab. hortō, L. (hortō), V. horte Plur. N. hortī, Ac. hortōs, G. hortōrum, D., Ab., L. hortīs

we find in Oscan (remembering that ú was probably pronounced just like ō)

Sing. N. húrz, Ac. húrtúm, G.*húrteis, D. húrtúí, Ab. *húrtúd, L. *húrtei, V. ? Plur. N. *húrtús, Ac. *húrtúss, G. *húrtúm, D., Ab., L. *húrtúís.

On this kind of evidence, one can say that Latin and Oscan in the second century BC were about as similar as Spanish and Portuguese are today.

Consciousness of Latin as a language with its own identity began in the words of the poet Gnaeus Naevius, one of the very first in the Latin canon, writing from 235 to 204 BC. He wrote his own epitaph, showing either a concern that the language was in danger of decay, or an inordinate pride in his own literary worth!

Naevius is the earliest Latin poet whose works have survived. (He was actually a man of Campania and so probably grew up speaking Oscan.) But when these words were written, at the end of the third century BC, Rome already had three centuries of forthrightly independent existence behind her, and we know that Latin had been a written language for all of that time. Our earliest surviving inscriptions are from the sixth century BC.

Latin had been literate, then, but not literary: scribes will have noted down important utterances, but few will have consulted those records after the immediate need for which they had been made. One ancient historian recounted that important laws were stored on bronze pillars in the temple of Diana on Rome’s Aventine Hill,3 and at least one ancient inscribed stone has been found in the Roman Forum.4 There was a tradition at Rome that the law was set down publicly on Twelve Tables in 450, but the fragments that survive, quoted in later literature, are all in suspiciously classical-looking Latin.5 It seems unlikely that there was any canon of texts playing a part in Roman education in this early period.* Famously, the important written texts, such as the Sibylline Books, consulted at times of crisis by the Roman government, were not in Latin but in Greek. The absence of a literary tradition in Latin until the second century seems to have allowed speakers to lose touch with their own language’s past, in a way that would have been unthinkable, say, for Greeks in the same period.

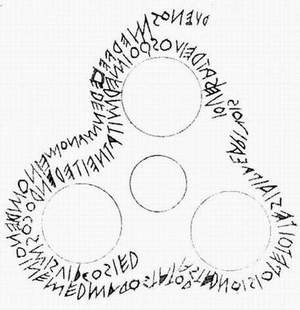

The Duenos ceramic, a tripartite vase of uncertain, but perhaps erotic, use. It holds the earliest substantial inscription in Latin (sixth to fifth centuries BC).

In fact, about three generations after Naevius, the historian Polybius managed to locate the text of a treaty that had been struck between Rome and Carthage, explicitly dating it to the first year of the Roman Republic, 508 BC (“under Lucius Junius Brutus and Marcus Horatius, the first consuls after the expulsion of the kings, twenty-eight years before Xerxes crossed into Greece”). He commented, “We have transcribed this, interpreting it to the limits of accuracy possible. But such a great difference in dialect has arisen between modern and ancient that the most expert Romans can barely elucidate parts of it, even after careful study.”6

He then quoted it in full, but tantalizingly only in Greek translation. However, one of the few inscribed survivals from earlier Latin may offer a hint at the kind of difficulties those Roman experts were encountering. Latin grammar had moved on quite smartly in those two hundred years; and many old inscriptions remain enduringly obscure, even though we now can approach them with a comparative knowledge of other Indo-European languages inconceivable to contemporaries.

Consider for example the oldest substantial example, on the famous DVENOS ceramic, a tripartite, interconnecting vase rather reminiscent of a Wankel engine. Found in Rome in 1880, it is dated to the sixth or early fifth century BC, the same period as that early treaty.

The inscription is in three lines, which may be transcribed as

IOVESATDEIVOSQOIMEDMITATNEITEDENDOCOSMISVIRCOSIED

ASTEDNOISIOPETOITESIAIPAKARIVOIS

DVENOSMEDFECEDENMANOMEINOMDUENOINEMEDMALOSTATOD

and which are conjectured to mean

He who uses me to soften, swears by the gods.

In case a maiden should not be kind in your case,

but you wish her placated with delicacies for her favours.

A good man made me for a happy outcome.

Let no ill from me befall a good man.7

This is unlikely to be fully correct—some of the vocabulary may simply be beyond our ken because the words died out—but even if it is, it presupposes that the words here must have changed massively over three centuries to become part of a language that Naevius would have recognized. Here is a reconstruction into classical Latin, with the necessary changes underlined:

iurat diuos qui per me mitigat.ni in te_comis virgo sietast [cibis] [fututioni] ei pacari vis.bonus me fecit in manum munus. bono_ne e me_malum stato

Virtually every word had changed its form, pronunciation, or at least its spelling between the sixth and the third centuries BC. This shows what rapid change for Latin occurred in these three centuries, comparable to what happened to English between the eleventh and the fourteenth centuries AD, when Anglo-Saxon (typified by the Beowulf poem), totally unintelligible to modern speakers, gave way to Middle English (typified by Chaucer’s writings), on the threshold of the modern language.

The inscription that circles the Duenos ceramic. Written in a highly archaic form of Latin, it appears to offer a love potion.

Yet (again like English), as reading and writing became more widespread, the pace of change in the language was to slow dramatically. Naevius’ poetry of the third century remained comprehensible to Cicero in the first, and indeed Plautus’ comedies, written in the early second century BC, were still being performed in the first century AD. Those plays are in fact written in a Latin close to the classical standard, canonized by Cicero and the Golden Age literature that followed him, a literary language that was simply not allowed to change after the first century BC, since every subsequent generation was taught not only to read it but to imitate it.

But why did this language, which only came to a painful self-awareness in the third century BC, go on to supplant not only all the other languages of Italy but almost all the other languages of western Europe as well? In the sixth century BC, a neutral observer could only have assumed that if Italy was destined to be unified, it would be under the Etruscans; and in the third century BC, Latin was still far less widely spoken than Oscan. Where did it all go right for Latin, and for Rome?