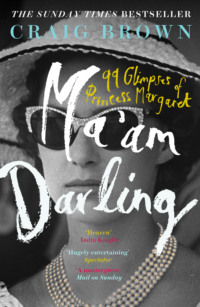

Ma’am Darling: 99 Glimpses of Princess Margaret

PETER TOWNSEND: Darling, you got to let me know

Should I stay or should I go?

PRINCESS MARGARET: If you say that you are mine

I’ll be here ’til the end of time

BOTH: So you got to let me know

Should I stay or should I go?

By now I was hallucinating. The Princess was everywhere and nowhere. It seemed as though everyone I bumped into had met her at one time or another, and had a story to tell, generally about her saying something untoward and an uneasy atmosphere ensuing. At the same time my brain was becoming entangled with the spaghetti-like argy-bargy of the Townsend affair, as knotted and impenetrable as the causes of the First World War.

I would spend hours puzzling over the same not-very-interesting anecdote told about her by different people, each contradicting the other. Should I go for the most likely, the funniest, the most interesting, or even, as part of my noble effort to write a serious book, the dullest? And which was which? I found it increasingly hard to judge. Should I favour one version of events over the other, or should I risk boring the reader by doggedly relaying every variant?

Just as the writers of the four gospels of the New Testament offer contrasting views of the same event, so do those who bear witness to the life and times of Princess Margaret. To pick just one example, here are two different versions of a quite humdrum little story about Lord Snowdon, Princess Margaret, a cigarette and a cushion. I have put them side by side, for the purposes of compare and contrast.

The first is from Of Kings and Cabbages (1984), a memoir by Peter Coats, former ADC to General Wavell,* boyfriend of Chips Channon, and editor of House and Garden magazine, widely known by the nickname ‘Petti-Coats’:

Tony Snowdon was having a mild argument with his wife, Princess Margaret, and, having lit a cigarette, flicked the match towards an ashtray and it fell into Princess Margaret’s brocaded lap. HRH brushed it off quickly and, rather annoyed, said, ‘Really, Tony, you might have burned my dress.’ To which came the reply, ‘I don’t care. I never did like that material.’ The princess drew herself up and said very grandly, ‘Material is a word we do not use.’

I admit to having told this story several times, and it always arouses a storm-in-a-cocktail-glass of discussion. What other word? Stuff, perhaps?

So there we are. Now take a look at this second version of the same event, which comes from Redeeming Features (2009), an enjoyably baroque memoir by the interior decorator and socialite Nicky Haslam:

We joined a party at Kate and Ivan Moffat’s, where the growing distance and determined one-upmanship between Princess Margaret and Tony Snowdon was all too evident. Bored, Tony played with a box of matches, flicking them, lit, at his wife. ‘Oh, do stop,’ she said. ‘You’ll set fire to my dress.’ Tony glowered. ‘Good thing too. I hate that material.’ Princess Margaret stiffened. ‘We call it stuff.’

Which to pick? The Coats version is milder, the Haslam version more extreme. Coats has Snowdon lighting a cigarette and flicking a single match with the intention of making it land in an ashtray; Haslam has him playing with an entire box of matches out of boredom, and aiming and flicking the lit matches, one by one, at Princess Margaret. According to Coats, the Princess says,

‘Material is a word we do not use.’

Coats then speculates about a feasible substitute. But Haslam makes no mention of her declaring ‘Material is a word we do not use’; he simply has her observing,

‘We call it stuff.’

We will never know which version is true, or truer, or if both are false, or half-true and half-false. If you could whizz back in time and corner both men as they left the Moffats’ house, I imagine that each would swear by his own story, and someone else emerging from the same party – Lord Snowdon, or Princess Margaret, or one of the Moffats, for instance – would say that both of them had got it wrong, and the truth was more mundane, or more civilised, or more outrageous. To me, as the self-appointed theologian of that particular contretemps, Coats’ version sounds marginally the more probable. A succession of lit matches flicked across a sofa strikes me as a little too chancy and hazardous, particularly if flicked in someone else’s house. Moreover, ‘Material is a word we do not use’ sounds more imperiously Princess Margaret than ‘We call it stuff.’ On the other hand, Nicky Haslam is a keen observer of human behaviour, and has a knack for detail.

Even if we agree to settle for a judicious mish-mash of the two accounts, we are still obliged to embark on a discussion of late-twentieth-century royal linguistics. Both accounts agree that ‘material’ was a word offensive to Princess Margaret, and perhaps even to the entire (‘we’) Royal Family. But why? As words go, it has a perfectly good pedigree: it dates back to 1380, and was employed by Geoffrey Chaucer. On the other hand, though ‘stuff’ may sound more aggressively modern, coarse and general, it in fact predates ‘material’ by forty years. ‘Stuff’ originally meant fabric – in particular the quilted fabric worn under chain mail. It was centuries before it was demoted into a catch-all term applied to anything you couldn’t quite remember the right name for. So the Princess’s etymological instinct turns out to have been spot-on.

Or – forgive me – was her preference for ‘stuff’ over ‘material’ an unconscious throwback to her family’s Germanic roots? The German for material is ‘stoff’, so it’s possible the Royal Family’s liking for ‘stoff’ has been handed down from generation to generation, its basis lost in time.

So much for that. As you can see, when push comes to shove, even the most humdrum royal anecdote can open up any number of different avenues of enquiry. For instance, who on earth were the Moffats? It would be easy to find out, and a true scholar would probably include their CVs either in the text itself or in a learned footnote. But there is only so much a reader can take. Does anyone really need to know?*

And what about all the other words Princess Margaret didn’t like? Should I squeeze them in too? After all, she could take fierce exception to words she considered common – but she chose those words pretty much at random, so that people who weren’t on the alert would utter one of them, and set off a booby trap, with the shrapnel of indignation flying all over the place. The Princess strongly objected to the word ‘placement’, for example, yet it’s just the kind of word her friends and acquaintances would have instinctively used while dithering over who to place where around a dining table, probably thinking the word was rather classy. But no! The moment anyone said ‘placement’ – ka-boom! – all hell would break loose. ‘Placement is what maids have when they are engaged in a household!’ Princess Margaret would snap, insisting on the expression ‘place à table’ instead. And the nightmare wouldn’t end there. Even those who had managed to shuffle to their allocated seats without uttering the dread word were liable to be caught out the next morning, at breakfast time, when the Princess would reel back in horror if she heard the phrase ‘scrambled eggs’, declaring irritably, ‘WE call them “buttered eggs”!’

And so a biography of Princess Margaret is always set to expand, like the universe itself, or, in more graspable terms, a cheese soufflé, every reference breeding a hundred more references, every story a thousand more stories, each with its own galaxy of additions, contradictions and embellishments. You try to make a haybale, but you end up with a haystack. And the needle is nowhere to be seen.

* Field Marshal Wavell (1883–1950) once sat next to Princess Margaret over lunch. Tongue-tied at the best of times, he struggled to think of something to say. At last, he was seized by an idea!

‘Do you like Alice in Wonderland, Ma’am?’

‘No.’

* Oddly enough, the answer is probably yes. As it happens, Ivan Moffat was a film producer and screenwriter (A Place in the Sun, The Great Escape, Giant). Born in Cuba in 1918, he was the son of the actor-manager Sir Herbert Beerbohm Tree, the nephew of Sir Max Beerbohm, and the uncle of Oliver Reed. In Paris in the forties, Moffat was friends with Sartre and de Beauvoir, and he had affairs with two notable women who appear elsewhere in this book – Lady Caroline Blackwood and Elizabeth Taylor. Kate, his second wife, was a direct descendant of the founder of W.H. Smith, and a lady-in-waiting to the Queen Mother. So now you know.

12

In 1993, the sixty-two-year-old Princess Margaret stood by a dustbin piled with letters and documents, while her chauffeur put a match to them.

David Griffin had been a professional driver for many years – double-decker buses, lorries, the 3 a.m. coach for Harrow Underground workers – before, one day in 1976, spotting a newspaper advertisement for a royal chauffeur. He leapt at it. ‘I wouldn’t say I was an absolute royalist. I just thought they were the ultimate people to work for, the pinnacle of the chauffeur world.’

He was to spend most of the next twenty-six years driving Princess Margaret around. He once calculated that he spent more time with her than with his own mother, though he spoke to her very rarely. ‘She was part of the old school and she never changed from day one. She was very starchy, no jokey conversation. She called me Griffin and I called her Your Royal Highness.’ By the end of a typical trip to Sandringham, she would have uttered a total of two words: ‘Good’ and ‘morning’.

‘There was no need to say more, she knew I knew the way. I saw myself as part of the car, an extension of the steering wheel. A proper royal servant is never seen and never heard. We preferred to work in total silence, so we didn’t have to be friendly. We never used to try and chat. They used to say Princess Margaret could freeze a daisy at four feet by just looking at it.’

During this time, the Princess owned a Rolls-Royce Silver Wraith (fitted with a specially raised floor to make her look taller), a Mercedes Benz 320 for private use, a small Daihatsu runabout, and a Ford Transit minibus for ferrying friends around. As Griffin describes it, ‘Six or seven people would pile in and shout: “Orf we go on our outing.”’ The Princess herself had never taken a driving test. Why bother?

Griffin’s day began at 8 a.m., when he gave the cars a thorough polish, inside and out. He then collected any letters to be delivered, a category that included anything of the slightest importance and quite a few of no importance at all. These would be handed to him by the Princess’s private secretary or a lady-in-waiting, or, every now and then, by Her Royal Highness in person. Occasionally he had to take a letter to her former husband, Lord Snowdon (‘very pleasant and nice with impeccable manners’), who would invariably ask him to wait while he composed a reply. But if Snowdon telephoned Kensington Palace to ask whether Griffin could collect a message for Princess Margaret, the Princess would usually reply, ‘No, he’s got other things to do.’

As long as she had no official duties, her daily routine remained unvaried. Shortly after 11 a.m., Griffin would drive her to her hairdresser, latterly David and Joseph in South Audley Street. ‘Then she would go out for lunch at a nice restaurant. Then she’d come back to the palace and have a rest.’ Around 4.30 p.m. he would drive her to Buckingham Palace for a swim in the pool. ‘Then she’d go to the hairdresser’s for the second time in one day. Then I’d drive her to pre-theatre drinks, then to the theatre, then a post-theatre dinner. And I’d finish about 3 a.m. Sometimes this would happen every night. And I’d always be up at 8 a.m. At the weekend, I’d drive her to the country. If she travelled to Europe, I’d get there first and pick her up at the airport in Prague, for example, so she never thought anything was different.’

On a number of occasions, the Princess asked Griffin to drive her to Clarence House. After a couple of hours she would emerge with a large binbag filled with letters, which she would hand to him. Back at Kensington Palace, she would put on a pair of yellow rubber gloves and help him bundle the letters, still in their bags, into a metal garden dustbin in the garage before ordering him to set light to them. ‘We did it several times over a period of years,’ says Griffin. ‘A lot of it was old, going back donkeys’ years, but I saw letters from Diana among them. We must have destroyed thousands of letters. I could see what it was we were burning. She made it very clear it was the highly confidential stuff that we burned. The rest was shredded in her office.’

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.

Вы ознакомились с фрагментом книги.

Для бесплатного чтения открыта только часть текста.

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера:

Всего 10 форматов