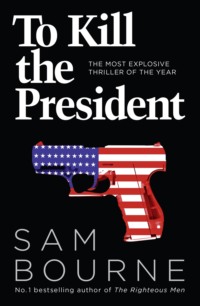

To Kill the President: The most explosive thriller of the year

‘Look at the paper, Maggie.’

‘“First states roll out registry of Muslim citizens. Arizona, Texas, pilot new scheme.”’

‘Not that story. The one I’ve marked, next to it. Look where we are with eighteen to twenty-four-year-olds.’

‘Twenty-three per cent approve, seventy-four per cent disapprove, three per cent don’t know.’

‘Exactly. Twenty-two last month, now up to twenty-three. The young are coming round to us, Maggie. I can feel it.’ And with that he threw his head back and burst into song, his own version of a David Bowie classic.

‘Allllllt-Right, we are the young Americans!’ As he repeated the line, he did a slow turn, his eyes closed, head nodding – a middle-aged rocker on stage in a nostalgia tour.

Maggie said nothing.

‘OK, you got me. That’s not why I came in here.’

‘If it’s about that calendar, there’s no way that’s going back up.’

‘I noticed the lovely Miss May was missing in action. Are you to blame for that? Are we still doing that, the student protest thing?’

‘Under the legal definition of sexual harassment, just putting that on the wall counts as creating a hostile environment.’

He smiled and shook his head. ‘None of you get it, do you? Not even a little bit. Don’t you realize that’s why the folks elected the big guy last November? I mean, sure it helped that his opponent had endangered national security by using an unsecured phone.’

Maggie rolled her eyes.

‘But the main reason was precisely this kind of bullshit. Because folks were sick to their hind legs of prissy little missies spouting horseshit like “hostile environment”.’ He made the quotation marks with his fingers, delivering the two-word phrase in a high-pitched voice now accompanied by an effeminate swing of the hips. ‘People are sick of being told that being a normal, red-blooded white man is a federal crime.’

‘I’m sure you didn’t come here to re-fight the election campaign, Mac.’

‘No, but as it happens, it’s all relevant.’ McNamara helped himself to a chair, sat back in it and put his shoeless, socked feet on her desk. Maggie all but recoiled.

‘Here’s the thing,’ he said. ‘I need you to make something go away.’

Maggie raised her eyebrows.

‘It came up in the campaign and it’s coming up again now.’

Maggie still said nothing. She saw no reason to make this any easier for him.

Eventually, he lowered his voice. ‘I think you Washington insiders call them “bimbo eruptions”.’

Maggie paused. ‘Do you mean the President has been having extra-marital affairs?’

‘No!’ Mac smiled. ‘Not affairs. Nothing that you’d call an affair.’

‘Oh, you mean sexual assault. Grabbing random women.’

‘I mean accusations of that.’

‘More accusers coming forward? People from the past, alleging that—’

‘Partly that.’

‘Oh, so not just the past? The present. Here? In this place? Jesus, Mac, they impeached the last man who did that.’

‘Oh, I’m not worried about that. The House leadership are rimming our asshole. The tongue’s in deep.’

Maggie did her best to show no expression. She knew he wanted a reaction out of her and she was damned if she was going to give it to him. He went on: ‘None of them will dare move on this. Remember, he’s bigger in their districts than they are. But it’s a distraction. I need you to make it go away.’

‘Sounds like a matter for his personal lawyer.’

‘No. He’s the President now. An attack on him is an attack on the Presidency.’

‘That’s not quite—’

‘Besides, you’re the right person for this.’ He began to get up. Before Maggie had a chance to ask what he meant, he leered, ‘You’ve got the right equipment.’

He closed the door after him, allowing Maggie to sink her head into her hands. She needed to see Richard.

They’d only been dating a couple of months, but given how many of her old friends had left the White House, he had become the default confidant. Three years younger than her and absurdly handsome – one of those Washington men who, no matter how early their first meeting, had already managed a run – he was far from her usual type. Appointed during the transition, he had nevertheless shared her doubts about the wisdom of serving the new administration. Along with the former president, Richard Parris had been a big influence on her decision to keep at it. ‘Maggie, we’re powerless on the outside. Imagine how guilty we’d both feel if we saw something horrible happen and we could have done something – anything – to stop it.’

At first Richard didn’t quite understand why that argument resonated with her so deeply. There was a reason, but she tried to hold it back from Richard the way she held it back from everyone else. Eventually, in bed one night, she gave in and told him. Just thinking about that now brought it back: a guilt so present it was almost physical, bobbing to the surface like a cork. She pushed it back down, a psychological manoeuvre she made at least a dozen times a day.

She headed down the stairs now to find him, to suggest they take a walk. She needed to unload. She began rehearsing the speech she’d make. We’re not softening the blow, Richard. We’re legitimizing it. We’re nothing more than a fig leaf for them. I did not come to Washington to help an abuser of women get away with it. That is not the reason—

But her train of thought was interrupted. She had just turned the corner when she saw a group emerging from the Oval Office. Richard was among them – odd, for someone at his level – but he didn’t notice her. Instead he was busy smiling and laughing with the only woman in the group, whose hair alone made her instantly recognizable. Thick and lustrous, it shone with wealth. There was no mistaking her.

Now Richard was showing the woman his phone, bringing a warm smile and a reciprocal gesture, as she showed him hers. Their faces – young and gorgeous, as they appeared to Maggie – seemed to be glowing in the electronic light. It was clear. Her boyfriend was flirting with the President’s daughter.

3

New York, Monday, 9.20am

Having zero charisma had its advantages, Bob Kassian reflected. Seated in business class on the shuttle to New York, a single Secret Service agent at his side, few people had bothered him. A couple of travellers had flashed him the thumbs-up. A reporter from Fox had tried to engage him in conversation at the gate, but Kassian had given such short, monosyllabic answers – delivered in his barely audible, low hush – that the woman had soon backed off. As for the rest, he reckoned they had simply not recognized him. He didn’t do the Sunday talkshows, he made few speeches. And that was just fine.

Especially this morning. He would have struggled to pose for selfies, grinning broadly with the fanboys in their correctly coloured baseball caps. How they revered his boss. If only they knew what he knew, if only they had seen what he had seen just a few hours ago. (A grim thought surfaced: perhaps it would make no difference. Nothing seemed to shift their devotion to this man.)

For the thousandth time he wondered if he had done the right thing. A backroom operative, he had never been a committed partisan. He had fallen in with this crowd simply because those were his friends and contacts. He had established a reputation as a man who could run things – big things – smoothly. After the army, everyone told him skills like his could make him a fortune. They were right. He went to New York, to one of the big financial houses, and was paid unimaginable sums. But he missed what he had loved most about the army: purpose. Politics seemed like a decent second-best.

As for this job? He knew what prompted the offer: he would be presented as the responsible adult on the team, his calm, technocratic presence a token of reassurance to a nervous party establishment. It sounded old-fashioned but he felt it was his patriotic duty to say yes. If he hadn’t, one of the crazies surely would have. And, from the inside, he could perhaps act as a restraining influence, holding back a President who would otherwise be listening to the swivel-eyed extremists led by Crawford McNamara who clearly had the ear of the Commander in Chief.

Now in the back of the car ferrying him to Manhattan, he closed his eyes, grateful to be cocooned, however briefly.

Somehow, they had survived. The sun had come up, the sky had not fallen in. Civilization had not ended. For that he could not congratulate either himself or his closest ally, Jim Bruton. It wasn’t their intervention that had stopped the President giving the order.

The truth was, he had been about to do it. The President had been put through to the colonel in the Pentagon War Room, who had, following procedure, issued the challenge code: Echo Bravo, or whatever it was. The President had responded, giving the codes that confirmed his identity: say, Delta Zulu. And then he had told the war room his decision, explaining that he had chosen from the menu of strike options and selected Option B.

At that point – and kudos to him for the effort – the colonel had suggested that the President might want to consider going a la carte for this highly unusual situation. Highly unusual in that the United States was not under attack, the only scenario for which anybody had been trained or prepared. Nice try on the colonel’s part: ordering a special ‘dish’ would have taken hours or days. It would have bought Kassian and the others what they needed: time. But the President was adamant. Option B. Now.

Apparently, there was a stillness in the room then. Even the President briefly stopped raging. The colonel turned to the team in the War Room and gave the signal. They set about formatting the ‘emergency action message’ that would unleash the forces reflecting the President’s choice – the bombs that would have destroyed the world. That task would have taken about a minute.

But after about fifteen seconds, a young intelligence analyst told the colonel to wait. He had seen a report of a new statement from Pyongyang, apparently backing down on the earlier one that had so offended the President. It had just come in.

The line connecting the Pentagon and the White House was still open and the colonel spoke. ‘Mr President, we have reason to believe the North Koreans have backed down.’

‘What’s that?’

‘Sir, they have fully capitulated. An abject apology.’

‘Are you sure?’

‘That is our information, sir, yes.’

‘OK.’

There were twenty seconds left till the action message went live.

‘Does that mean you wish to abort the order, sir?’

‘What did the North Koreans say exactly?’

‘Sir, we have ten seconds to decide. Should I abort the order?’

‘Fuck them.’

‘Sir?’

‘All right, all right. Abort.’

And that’s how they had averted Armageddon. One sharp-eyed desk officer may well have saved the world. Quick-witted and creative, more than sharp-eyed, as it turned out. Jim Bruton arrived at the Pentagon minutes afterwards, where the colonel on duty discreetly let him know him that the supposedly abject statement from North Korea, fortuitously released just seconds before the trigger was about to be squeezed, was more a work of wishful thinking than reality. The analyst had correctly read the situation, understanding that his immediate commanding officer and the Defense Secretary were desperately looking for an excuse to delay, and he had provided them with what they needed. In the process, he had left Bruton with a new headache – he now needed to generate a text that looked plausibly like a full apology from Pyongyang – but, given the stakes, that could be forgiven. Jim had immediately recommended the officer and the entire duty team in the War Room for a Defense Superior Service Medal.

Kassian had now reached the Waldorf Astoria hotel. Without looking either left or right, he made straight for the elevators, letting his Secret Service agent clear a path, press the button and select the floor. Avoiding eye contact with hotel guests, he caught himself in the mirror. He retained a full head of hair, but it seemed to be greying by the day. Back in January, it was all dark. He was still tall, still lean. His wife insisted he remained handsome: ‘Real handsome, not Washington handsome,’ was how she put it. But what he saw in his eyes was something else: a look of alarm and worry that was becoming permanent. The face staring back at him seemed haunted.

They stepped out on the fifth floor and went to the suite whose number he had been given. They were let in by a warm, rounded blonde woman in her mid-forties who introduced herself as the Swedish ambassador to the United Nations. She struck him as unexpectedly maternal.

There was an awkward moment or two as Kassian’s agent checked for security, including – especially – for bugs. Then the agent was introduced to his counterpart, who did the same. Only when both were satisfied, and had nodded in the direction of the Swedish host, did she give the signal that, a second later, meant a door – presumably to one of the bedrooms – was opened. Through which stepped out a man Kassian recognized as the Ambassador to the United Nations of the People’s Republic of China.

Kassian, still standing, offered his hand, which the Chinese diplomat took firmly. Kassian knew the man was just a year older than he was: fifty-one. He wore a plain blue suit, an off-white shirt and oversized, 1970s-style glasses. No retro chic was intended. They were just old.

Their host gestured for them both to sit down in the living area – two couches, armchair, coffee table – at the centre of the suite. In an accent that suggested an expensive education in England, she spoke first.

‘Gentlemen, as you know, we were asked to make a space available for you to talk in a way that would remain completely unrecorded and confidential. It was Mr Kassian’s suggestion that you meet here, rather than in Washington, where he suspected discretion would be harder to achieve, especially perhaps for him.’ She smiled. ‘He was also aware, with all due respect to the Republic’s ambassador in Washington, that you, Mr Lei, are widely reputed to be even closer and, dare I say, more influential with your government in Beijing.’

She paused and continued. ‘I should stress that Sweden has no selfish interest of our own in whatever issue has brought you both here. But you will both be aware of Sweden’s great and historic interest in advancing the cause of peace in the world. If there is anything that can be done to avoid war, then my country will give whatever we can.

‘I repeat that what is said in this room will remain confidential. No word of it shall be spoken by us. We will deny this meeting ever took place. No one knows any of us are here. This room is booked in the name of an anonymous Swedish businessman. As it happens, there are quite a few of those.’ That did as was intended, and brought smiles from both men. ‘Mr Kassian, it was you who suggested we meet. Why don’t you begin?’

‘Thank you, ambassador. And thank you, sir, for coming to meet me here today and at such short notice. You know, I hope, that I would not have asked our mutual friend,’ he nodded towards the Swede, ‘to bring us together unless I regarded it as of the gravest importance.’

Zheng Lei looked at him impassively.

Kassian glanced down at his own hands, wondering if they might start trembling again. ‘I don’t know how much, if anything, you know of what happened last night in the White House.’ No response from the man opposite. ‘But I’m going to be extremely frank. I can see no other way.’

He cleared his throat. He had thought about what he would say – on the plane, in the car – but that had not prepared him for the sensation of actually saying it.

‘In the early hours of this morning, my country came within ten seconds – less than ten seconds, in fact – of launching an all-out nuclear assault on the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea and,’ he heard a dryness enter his throat, ‘the People’s Republic of China.’

The Swedish ambassador gasped at that. An involuntary, and entirely genuine, sound. Her hand now covered her mouth. Kassian went on.

‘The President had given the order. The War Room at the Pentagon was in the process of encrypting and communicating that order to nuclear commanders around the world, including firing crews based on land, in our underground launch facilities, as well as those on submarines and onboard our bombers in the sky. Only an ingenious and brave intervention from one of our military officers, at the very last moment, caused the order to be aborted.’

The Chinese ambassador kept his gaze on the coffee table positioned between them. Kassian decided to read that as a reaction of sorts: perhaps this man was fearful of looking him in the eye, lest he give himself away. Kassian spoke again.

‘What prompted the attack was the statement issued by the DPRK late last night our time. It appeared to taunt the President. If I may quote.’ Kassian reached into his breast pocket, and unfolded a single piece of paper. ‘“The Workers’ Party knows it confronts in Washington a paper tiger, a coward and a small man. We will demonstrate our strength – for we know our enemy’s weakness.’”

Still Zheng said nothing. Kassian went on.

‘Ordinarily, under previous administrations perhaps, such statements might be dismissed as rhetoric.’ He thought he saw the tiniest hint of a nod from the ambassador. It encouraged him.

‘But these are not ordinary times. For one thing, the DPRK has repeatedly signalled its intention to build a nuclear weapon capable of reaching the west coast of the United States. Capable of hitting Los Angeles. Our intelligence suggests that the DPRK is either at, or close to, that stage.

‘However there is a more – how should I put this? – pressing way in which these are not ordinary times. The leader of my country is not a politician. And he is not a military man. He hears statements like these’ – he held up the sheet of paper – ‘the way a young man might hear them in a bar.’ He hadn’t planned to say this; he wondered if he had made a mistake. ‘He hears them as a provocation. He believes he is being dared to prove the North Koreans wrong.’

At that, Zheng sat up, readying himself to speak. Kassian did not know if that meant he had succeeded or failed.

‘Mr Kassian, are you a student of history?’ His English was impeccable.

‘Excuse me?’

‘Your résumé says you studied the liberal arts at Princeton. But it doesn’t tell me if you studied history.’

‘Some.’

‘I see. Well, I am a student of history. My specialism is the history of this country, in fact. Especially the last century. I took great interest in the Presidency of Richard Nixon. I wrote my master’s thesis on Mr Nixon’s relations with Asia.’

‘I see.’

‘Do you know why I bring this up now?’

‘I sense you’re about to tell me.’

‘Because Mr Nixon was very careful to have his closest aides – Dr Kissinger especially – travel the world warning everyone that their boss was a madman.’ At this he smiled. “Crazy! Unhinged!” Nixon was not offended. He encouraged it. He wanted America’s enemies to be frightened. “America has all these bombs – and Nixon is crazy enough to use them!”’

‘And you think that’s what I am doing now?’

‘History does not repeat itself, Mr Kassian. But it does sometimes rhyme.’

The American found himself looking to the Swedish ambassador, by way of an appeal. She nodded, but only to encourage him to reply. She was not about to take sides.

‘Mr Lei. I have taken quite a risk by coming here this morning. My President does not know I am here. I would be fired if he knew. I can assure you I am not doing his bidding.’

‘Then why are you here?’

‘I’m here because I am scared.’ The words surprised Kassian as much as the other two, perhaps more. ‘I don’t think you understand what I’m telling you. Your neighbour was within seven or eight seconds of being wiped off the map this morning and your country within seconds of being hit by a nuclear bombardment. Every last one of North Korea’s people would have been killed, along with millions of your own countrymen. Children. Families. Perhaps even your own family.’ Kassian thought he saw a shadow pass across Zheng’s face. ‘This is not a tactic. This is not a game. This is deadly fucking serious.’

‘Mr Kassian—’

‘No. Listen to me. I’m warning you because I think – no, I know – that this could end in catastrophe. For the entire planet. He’s ready to do it. He did do it. He gave the order.’

‘So why didn’t it happen?’

‘We found a way to stop him.’

‘How?’

Mr Kassian stole a sheepish look in the Swede’s direction. Without meaning to, he heard his voice dip. ‘We told him the DPRK had apologized for the statement.’

‘I see.’

‘It was the only way.’

‘So now you need my country to use its leverage over the Democratic People’s Republic to persuade them to make good on the lie you told to stop your “crazy” President blowing up the world?’

‘That’s about the size of it, yes. And the North Koreans need to do it soon. They also need somehow to backdate it, so it appears they issued the statement at around 3.45am Eastern Standard Time.’

Kassian hesitated before making that last request. Partly because he feared it might be asking too much, but also because he had wondered if it was even necessary. These days, you could probably get away with falsifying a timestamp: in this era when everyone was ready to shout ‘fake news’ about anything, who would know or care? Not the President, who paid no attention to detail and who barely read the papers put in front of him.

But Kassian knew that wouldn’t hold. Crawford McNamara, for one, immersed himself in the minutiae and was assiduous in his reading of documents. As a master purveyor of fake news, he rarely allowed himself to be a consumer of it.

‘That won’t be easy, Mr Kassian. The North Korean people are a very proud nation. They take pride in their defiance of the American tyrant. They will not fall to their knees.’

‘No one is asking them to fall to their knees, Mr Zheng. Just a form of words that gets us through to—’

‘You seem to forget something, Mr Kassian.’

‘What’s that?’

‘That North Korea and the United States now have something in common. Both these nations are led by very unpredictable men – with very thin skins.’

Kassian nodded. He knew it was bad diplomatic form to appear to be agreeing with criticism of one’s own leader, but he couldn’t help himself. Besides, it seemed to bear fruit. Zheng spoke again.

‘Nevertheless, I appreciate the approach you have made to me. I will see what can be done.’

Kassian hoped he hid his relief. ‘I am grateful, Mr Zheng. But I’m afraid I need to ask even more of you.’

The ambassador said nothing.

‘The reality is that so long as the DPRK is led by this man, his presence will provoke the President I serve. You might say that is unjust or disproportionate. Even that it is irrational. There are some who might well agree with you. But that is the fact of the matter. So long as North Korea is led by its current ruler, a great danger exists. The risk is mainly to the DPRK, of course, but China is mortally threatened too. He could have chosen to hit just North Korea last night. But his orders were to strike at China too. So long as that regime remains in place, your country is in grave danger. The whole world is in grave danger.’

‘You are asking the People’s Republic to topple the ruler of the DPRK? Seriously? This is the request you would have me discuss with my government?’

Kassian signalled that this was indeed his request.

Zheng smiled and said, ‘Now I know for sure that you are on this mission alone. Your State Department would never have let you come here saying such nonsense! This is craziness, Mr Kassian. Complete craziness.

‘Of course we would not do that. If we topple the regime in North Korea, the country would collapse in an hour and by nightfall it would be entirely ruled from Seoul. My government has not forgotten what happened to Germany in 1989. The Berlin Wall came down and, a day or two later, Germany was one country again, ruled by the west. A united Korea would be wonderful for America, but not so good for China. Like you say in the United States, “We have seen this movie before: we know how it ends!”’