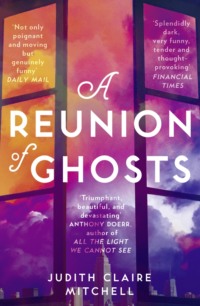

A Reunion of Ghosts

“But it didn’t work,” she said. “And I only bought it this morning.” She could hear her voice, the high pitch, the way it fluttered with nerves. “And I have the receipt. Look. It says right here your return policy is seven days.”

“We have a no returns policy for people who don’t know their asses from their elbows,” he said, and then he was back to struggling with the gate. It had gone off its tracks, was the problem. He shook it back and forth, jiggled it, jostled it. She saw that her presence was distracting him, exacerbating his struggle. She took a step back.

He mumbled something, but she didn’t try to make sense of it. She was still caught on what he’d said just before, his verbal addenda to the store’s return policy. She wondered if she’d possibly misheard him. His accent was so thick, after all, that she’d had to stare at his lips to make out his words. She’d stared even though his mouth repelled her, surrounded by that beard, all that short wiry hair. Her perverse mind suddenly compelled her to imagine kissing him, his tongue and facial hairs inside her mouth.

Something she tried never to think about came to her then. It was something that happened about a year earlier, on a warm spring night a few days after Vee and Eddie celebrated their first anniversary. This thing, it had been completely the fault of Joe Hopper. He’d whined and sulked for so long that night, she’d finally given in and agreed to have sex with a small group of their friends: three guys, including Joe, and one other woman.

One of the guys had just acquired a new waterbed. He’d right that minute finished filling it, he told Joe over the phone, and could think of no better way to break it in than with an orgy. Not that any of them had ever participated in an orgy or knew anyone who had. And not that Lady had any interest in an orgy. She couldn’t even abide the word, the way it sounded like some sort of obnoxious diminutive. Pudgy. Budgie. Orgy. But Time and Newsweek and Life and Look all reported that young people like Lady and Joe and their friends were constantly having group sex, and then there was Bob and Carol and Ted and Alice and also John Updike, and now Joe and some of the others had come to feel ripped off.

As they walked to the waterbed owner’s apartment, Lady was silent. It was more, she realized, than her not being interested. She was actively opposed. And even if she had been into it in theory, the specifics disturbed her. She didn’t like the 3:2 male/female ratio in general or the males and other female involved in particular.

On the other hand, she was always trying to prove that she was the opposite of your typical bourgeois dental receptionist, that, unlike all those women the Beats of the Upper West Side had married—women Lady sometimes recognized pushing carts in Gristedes—she was not the kind of wife whose conventionality could destroy an entire literary movement or even a single evening out. So okay, fine, she decided as she trudged alongside her husband. She would go along. When group sex is inevitable, she told herself, one should just lie back and enjoy it … and enjoy it … and enjoy it. Still, the phrase ad nauseam came to mind.

But in the end all her worried ruminating had turned out to be unnecessary. A bottle of Jack and several joints later, the only one of the three boys who could sustain an erection was the satyrical Joe Hopper, and Lady had consequently wound up having sex with no one besides her own husband. Later, while Joe fucked the other woman, the waterbed’s owner asked Lady to help him out by using her mouth, and when she demurred, he said well, what about her hand, and in the interest of not being a complete wet blanket she said okay, fine. “Obviously I’m not attracted to you,” he said pensively as she worked away with no discernible results. He was speaking more to himself than to Lady. “I always thought I was, but”—and here he looked down at the final arbiter—“you can’t argue with The Bone Dog.”

“Or with the absence of The Bone Dog,” the third guy said. He’d given up almost immediately, had taken himself and his own sad puppy to a mildewed easy chair where, still naked, he was reading a yellowed Columbia Spectator from 1968. The riots. The takeover of Grayson Kirk’s office. The good old days.

“Maybe if you pretend you don’t want it,” the waterbed owner suggested, and Lady said, “To be honest, Barry, I don’t.” She considered this a pretty clever response. She was telling the truth, yet Barry and The Bone Dog were free to interpret what she’d said as the pretense requested. But as it turned out, both were wise to her, and her words hurt their feelings. The Bone Dog turned the color of the sky before a thunderstorm and scuttled into itself. It had been small and retreating before; now it looked inside out.

Lady got up off the bed and put on her underpants. She turned her attention to selecting and stacking records on the turntable—the good hostess, even when it wasn’t her party—while Joe Hopper and the other woman went at it for a second time, moaning and grunting far more than was necessary while the unheated and underfilled waterbed gurgled and sloshed.

On the walk home Joe Hopper blamed the other guys’ failures on her. “You never act like you want it,” he said. “You radiate not wanting it. It’s so clear you don’t want it, you rendered a roomful of men at their sexual peak impotent.”

He kicked a trash can. She found it horrifying: she’d married a man who kicked trash cans. “Well, first of all, the room wasn’t full of men. It was just Barry and Norman. And second of all, Barry asked me to radiate not wanting it.”

Joe Hopper was neither mollified nor distracted. “Sometimes,” he said, “I feel like you tricked me into marrying you by pretending you liked sex.”

“No,” she said. “I tricked you into marrying me by pretending I liked you.”

“I want a divorce,” he said.

Outside the hardware store, this memory, in the way of memories, came and went in an instant. The hardware store owner was still wrestling with the gate. What struck her as she stood there holding the Phillips head was that as offensive as he was to her, it was plain she was equally offensive to him. She was, in his eyes, an ignorant woman, a fool who had gotten this far in life without learning the first thing about screws and screwdrivers, professionalism and dilettantism, asses and elbows.

She stepped forward, tried to place herself in the line of his peripheral vision. She was looking at his profile now. He would not turn his head even ninety degrees to look at her. All he did was shake the gate angrily and ineffectually. He reached up, trying to push it back, trying to start all over. As he did, his sleeves fell back, and—his age, his accent; it was no surprise, really—she saw the numbers.

She could never deny she saw them, and she could never deny she knew what they were. Our father, Natan Frankl, had come to the States from a displaced persons camp too. Though most of Lady’s recollections of him were faded or shadowed, some remained vivid.

But her own arm was already in motion. And maybe she didn’t care. Maybe the fact of those numbers didn’t make a damned bit of difference to her. Surely, along with the good and the innocent, plenty of assholes had been carted off to those camps: men who would someday abandon their daughters or insult their well-meaning customers or blithely do unto others as they wish hadn’t been done unto them. She had a theory. About 95 percent of all people populating this sad planet are assholes, she believed, regardless of race, religion, or creed. Accordingly, whenever you meet any member of any demographic, you have a 95 percent chance of meeting an asshole. Which, if you don’t know enough other members of the group, leads you to extrapolate your negative impression to the whole lot of them. This was why Lady believed in integration, mixed marriages, busing, anything that would increase the chances of people encountering and huddling together with the nonassholian 5 percent of humanity.

At this moment, though, she wasn’t reviewing her asshole theory. She was too busy feeling attacked and dismissed, abused and ignored. She was feeling, feeling, feeling, and so, untended and ungoverned, her arm did what it wanted to do, and what her arm wanted to do was throw the acid-green screwdriver at the hardware store owner’s head.

She never had much upper body strength, she never played sports of any kind—back in sixth grade, when she’d been forced to participate in the Presidential Physical Fitness Test, she’d scored in the lowest percentile for throwing—and so she hadn’t expected the screwdriver to go very far. She’d imagined it would fall and hit the sidewalk before it reached the head her arm had been aiming for. Instead the screwdriver did an elegant somersault, and as if assisted by an indiscernible breeze, its cruciform blade struck the man on the side of his cratered nose. He cried out—more in surprise than in pain, Lady felt certain—and covered his nose with both hands.

Now he was looking at her. Now he’d taken note. And now she was ignoring him. She squatted and darted under the half-closed gate. She knew exactly where to go, what to do. She didn’t run, just walked purposefully, to the aisle she wanted, to the right bin, and she took the one thing she was entitled to. Then she strode back to the door and upside-down-limbo’d into the slash of sunlight beyond it, where the stunned store owner stood, Phillips head at his feet, hands at his nose, blood seeping between his fingers.

She held up the screwdriver she’d taken, the rubbery blue. A couple of dollars less than the acid green; he was making money on the exchange. He didn’t care, though. “Oy, mein shnoyts,” he bleated from behind his hands. He dropped his arms, showed her the damage. It was nothing. A lot of blood, yes, but just from a single cut on the side of his left nostril. Nothing deep, nothing dangerous, although it did seem a fragile nose, all that excess purple flesh. It seemed as though it might hurt were someone even to touch it gently. Certainly it had made her wince to look at it.

The only way to avoid looking at it now was to leave. He was yelling about calling a policeman. There was something ridiculous in that—not a cop, not the police, but a policeman, like a small child with great faith in all public servants.

“Go ahead,” she said. “We’ll see whose side he takes,” and she turned and flounced off. She did—she flounced. Entitled and superior. A mean, spoiled brat. She who was none of those things, not ever.

Over the Puddle Styx, up the stairs, onto the train. Even now she wants to say that this was when she first began to grasp the enormity of what she’d done, but that would be a lie. She’d known what she was doing as she was doing it. Stop it, she’d thought as she raised her arm. Walk away, she’d thought as she threw the green tool. What the fuck are you doing? she inquired of herself as she slithered under the gate.

She hadn’t stopped, though. Hadn’t walked away. Thoughts versus feelings, and the winner had been feelings. A huge upset. No one would have predicted it.

But as the euphoria of her fury wore off, Lady became aware of a terrible pain inside her, sharp and systemic, as if she’d swallowed the millions of screws in the store and they were now scraping her organs as they tumbled through her bloodstream. She knew the reason for the pain. The entire encounter had been a test, and she’d failed, and she was hurting inside over that failure—because no matter what that man had done, no matter how badly he’d behaved, no matter how much of an asshole he’d been, she should have been kind. She’d seen the numbers. She’d known his life. Our family had played a part in that life, that living death.

And what had she done? She’d thrown the screwdriver.

To this day, whenever Lady thinks of the hardware store owner—and she thinks of him more often than you’d imagine—she feels the same shame, the same painful scraping of threaded metal through her body. She has to stop what she’s doing. She closes her eyes. She focuses on her breath. She inhales. She exhales. She tries to envision the store owner, wherever he is—dead, she supposes, given that the store is long gone, and he was an old man even in 1976—and when she has conjured him, she does her best to bathe him in love or as close to love as a sinner like Lady can manage.

But back then, as the train carrying Lady home tunneled underground, she felt no love for anyone. She felt only the pain. She was mortified, and she didn’t use the word casually. You didn’t have to be a Latin scholar to figure out its derivation. She wanted right then and there to mort.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.

Вы ознакомились с фрагментом книги.

Для бесплатного чтения открыта только часть текста.

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера:

Всего 10 форматов