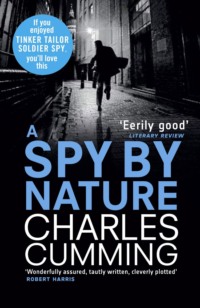

A Spy by Nature

Almost immediately, before the ink can be properly dry, Lucas snatches the document away from me and stands to leave. Distant traffic noise on the Mall. A brief clatter in the secretarial enclave next door.

‘Do you see the file on the table?’

It has been sitting there, untouched, for the duration of the interview.

‘Yes.’

‘Please read it while I am gone. We will discuss the contents when I return.’

I look at the file, register its hard red cover, and agree.

‘Good,’ says Lucas, moving outside. ‘Good.’

Alone now in the room, I lift the file from the table as though it were a magazine in a doctor’s surgery. It is bound in cheap leather and well thumbed. I open it to the first page.

Please read the following information carefully. You are being appraised for recruitment to the Secret Intelligence Service.

I look at this sentence again, and it is only on the third reading that it begins to make any sort of sense. I cannot, in my consternation, smother a belief that Lucas has the wrong man, that the intended candidate is still sitting downstairs flicking nervously through the pages of The Times. But then, gradually, things start to take shape. There was that final instruction in Lucas’s letter: ‘As this letter is personal to you, I should be grateful if you could respect its confidentiality.’ A remark that struck me as odd at the time, though I made no more of it. And Hawkes was reluctant to tell me anything about the interview today: ‘Just be yourself, Alec. It’ll all make sense when you get there.’ Jesus. How they have reeled me in. What did Hawkes see in me in just three hours at a dinner party to convince him that I would make a suitable employee of the Secret Intelligence Service? Of MI6?

A sudden consciousness of being alone in the room checks me out of bewilderment. I feel no fear, no great apprehension, only a sure sense that I am being watched through a small panelled mirror to the left of my chair. I swivel and examine the glass. There is something false about it, something not quite aged. The frame is solid, reasonably ornate, but the glass is clean, far more so than the larger mirror in the reception area downstairs. I look away. Why else would Lucas have left the room but to gauge my response from a position next door? He is watching me through the mirror. I am certain of it.

So I turn the page, attempting to look settled and businesslike.

The text makes no mention of MI6, only of SIS, which I assume to be the same organization. This is all the information I am capable of absorbing before other thoughts begin to intrude.

It has dawned on me, a slowly revealed thing, that Michael Hawkes was a Cold War spy. That’s why he went to Moscow in the 1960s.

Did Dad know that about him?

I must look studious for Lucas. I must suggest the correct level of gravitas.

The first page is covered in information, two-line blocks of facts.

The Secret Intelligence Service (hereafter SIS), working independently from Whitehall, has responsibility for gathering foreign intelligence…

SIS officers work under diplomatic cover in British embassies overseas…

There are at least twenty pages like this one, detailing power structures within SIS, salary gradings, the need at all times for absolute secrecy. At one point, approximately halfway through the document, they have actually written: ‘Officers are certainly not licensed to kill.’

On and on it goes, too much to take in. I tell myself to keep on reading, to try to assimilate as much of it as I can. Lucas will return soon with an entirely new set of questions, probing me, establishing whether I have the potential to do this.

It’s time to move up a gear. What an opportunity, Alec. To serve Queen and Country.

The door opens, like air escaping through a seal.

‘Here’s your tea, sir.’

Not Lucas. A sad-looking, perhaps unmarried woman in late middle-age has walked into the room carrying a plain white cup and saucer. I stand up to acknowledge her, knowing that Lucas will note this display of politeness from his position behind the mirror. She hands me the tea, I thank her, and she leaves without another word.

No serving SIS officer has been killed in action since World War Two.

I turn another page, skimming the prose.

The meanness of the starting salary surprises me: only seventeen thousand pounds in the first few years, with bonuses here and there to reward good work. If I do this, it will be for love. There’s no money in spying.

Lucas walks in, no knock on the door, a soundless approach. He has a cup and saucer clutched in his hand and a renewed sense of purpose. His watchfulness has, if anything, intensified. Perhaps he hasn’t been observing me at all. Perhaps this is his first sight of the young man whose life he has just changed.

He sits down, tea on the table, right leg folded over left. There is no ice-breaking remark. He dives straight in.

‘What are your thoughts about what you’ve been reading?’

The weak bleat of an internal phone sounds on the other side of the door, stopping efficiently. Lucas waits for my response, but it does not come. My head is suddenly loud with noise and I am rendered incapable of speech. His gaze intensifies. He will not speak until I have done so. Say something, Alec. Don’t blow it now. His mouth is melting into what I perceive as a disappointment close to pity. I struggle for something coherent, some sequence of words that will do justice to the very seriousness of what I am now embarked upon, but the words simply do not come. Lucas appears to be several feet closer now than he was before, and yet his chair has not moved an inch. How could this have happened? In an effort to regain control of myself, I try to remain absolutely still, to make our body language as much of a mirror as possible: arms relaxed, legs crossed, head upright and looking ahead. In time–what seem vast, vanished seconds–the beginning of a sentence forms in my mind, just the faintest of signals. And when Lucas makes to say something, as if to end my embarrassment, it acts as a spur.

I say, ‘Well…now that I know…I can understand why Mr Hawkes didn’t want to say exactly what I was coming here to do today.’

‘Yes.’

The shortest, meanest, quietest yes I have ever heard.

‘I found the pamphl–the file very interesting. It was a surprise.’

‘Why is that exactly? What surprised you about it?’

‘I thought, obviously, that I was coming here today to be interviewed for the Diplomatic Service, not for SIS.’

‘Of course,’ he says, reaching for his tea.

And then, to my relief, he begins a long and practiced monologue about the work of the Secret Intelligence Service, an eloquent, spare résumé of its goals and character. This lasts as long as a quarter of an hour, allowing me the chance to get myself together, to think more clearly and focus on the task ahead. Still spinning from the embarrassment of having frozen openly in front of him, I find it difficult to concentrate on Lucas’s voice. His description of the work of an SIS officer appears to be disappointingly void of macho derring-do. He paints a lustreless portrait of a man engaged in the simple act of gathering intelligence, doing so by the successful recruitment of foreigners sympathetic to the British cause who are prepared to pass on secrets for reasons of conscience or financial gain. That, in essence, is all that a spy does. As Lucas tells it, the more traditional aspects of espionage–burglary, phone tapping, honey traps, bugging–are a fiction. It’s mostly desk work. Officers are certainly not licensed to kill.

‘Clearly, one of the more unique aspects of SIS is the demand for absolute secrecy,’ he says, his voice falling away. ‘How would you feel about not being able to tell anybody what you do for a living?’

I guess that this is how it would be. Nobody, not even Kate, knowing any longer who I really was. A life of absolute anonymity.

‘I wouldn’t have any problem with that.’

Lucas begins to take notes again. That was the answer he was looking for.

‘And it doesn’t concern you that you won’t receive any public acclaim for the work you do?’

He says this in a tone that suggests that it bothers him a great deal.

‘I’m not interested in acclaim.’

A seriousness has enveloped me, nudging panic aside. An idea of the job is slowly composing itself in my imagination, something that is at once very straightforward but ultimately obscure. Something clandestine and yet moral and necessary.

Lucas ponders the clipboard in his lap.

‘You must have some questions you want to ask me.’

‘Yes,’ I tell him. ‘Would members of my family be allowed to know that I am an SIS officer?’

Lucas appears to have a checklist of questions on his clipboard, all of which he expects me to ask. That was obviously one of them, because he again marks the page in front of him with his snub-nosed fountain pen.

‘Obviously, the fewer people that know, the better. That usually means wives.’

‘Children?’

‘No.’

‘But obviously not friends or other relatives?’

‘Absolutely not. If you are successful after Sisby, and the panel decides to recommend you for employment, then we would have a conversation with your mother to let her know the situation.’

‘What is Sisby?’

‘The Civil Service Selection Board. Sisby, as we call it. If you are successful at this first interview stage, you will go on to do Sisby in due course. This involves two intensive days of intelligence tests, interviews, and written papers at a location in Whitehall, allowing us to establish if you are of a high enough intellectual standard for recruitment to SIS.’

The door opens without a knock and the same woman who brought in my tea, now cold and untouched on the table, walks in. She smiles apologetically in my direction, with a flushed, nervous glance at Lucas. He looks visibly annoyed.

‘I do apologize, sir.’ She is frightened of him. ‘This just came through for you, and I felt you should see it right away.’

She hands him a single sheet of fax paper. Lucas looks over at me quickly and proceeds to read it.

‘Thank you.’ The woman leaves and he turns to me. ‘I have a suggestion. If you have no further questions, I think we should finish here. Will that be all right?’

‘Of course.’

There was something on the fax that necessitated this.

‘You will obviously have to think things over. There are a lot of issues to consider when deciding to become an SIS officer. So let’s end this discussion now. I will be in touch with you by post in the next few days. We will let you know at that stage if we want to proceed with your application.’

‘And if you do?’

‘Then you will be invited back here for a second interview with one of my colleagues.’

As he stands up to leave, Lucas folds the piece of paper in two and slips it into the inside pocket of his jacket. Leaving the recruitment file on the table, he gestures with an extended right arm toward the door, which has been left ajar by the secretary. I walk out ahead of him and immediately begin to feel all the stiffness of formality falling away from me. It is a relief to leave the room.

The girl in the neat red suit is standing outside waiting, somehow prettier than she was at two o’clock. She looks at me, gauges my mood, and then sends out a warm broad smile that is full of friendship and understanding. She knows what I’ve just been through. I feel like asking her out for dinner.

‘Ruth, will you show Mr Milius to the door? I have some business to attend to.’

Lucas has barely emerged from his office: he is lingering in the doorway behind me, itching to get back inside.

‘Of course,’ she says.

So our separation is abrupt. A last glance into each other’s eyes, a grappled shake of the hand, a reiteration that he will be in touch. And then Philip Lucas vanishes back into his office, firmly closing the door.

THREE

Tuesday, 4 July

At dawn, five days later, my first waking thought is of Kate, as though someone trips a switch behind my closed eyes and she blinks into the morning. It has been like this, on and off, for four months now. Sometimes, still caught in a half dream, I will reach for her as though she were actually beside me in bed. I try to smell her, try to gauge the pressure and softness of her kisses, the delicious sculpture of her spine. Then we lie together, whispering quietly, kissing. Just like old times.

Drawing the curtains, I see that the sky is white, a cloudy midsummer morning that will burn off at noon and break into a good blue day.

All that I have wanted is to tell Kate about SIS. At last something has gone right for me, something that she might be proud of. Someone has given me the chance to put my life together, to do something constructive with all these mind wanderings and ambition. Wasn’t that what she always wanted? Wasn’t she always complaining about how I wasted opportunities, how I was always waiting for something better to come along? Well, this is it.

But I know that it will not be possible. I have to let her go. Finding it so difficult to let her go.

I shower, dress, and take the tube to Edgware Road, but I am not the first at work. Coming down the narrow, sheltered mews, I see Anna up ahead, fighting vigorously with the lock on the garage door. A heavy bunch of keys drops from her right hand. She stands up to straighten her back and sees me in the distance, her expression one of unambiguous contempt. Not so much as a nod. I push a splay-fingered hand through my hair and say good morning.

‘Hello,’ she says archly, twisting the key in the lock.

She’s growing her hair. Long brown strands flecked with old highlights and trapped light.

‘Why the fuck doesn’t Nik give me a key that fucking works?’

‘Try mine.’

I steer my key in toward the garage door, a movement that causes Anna to pull her hand out of the way like a flick knife. Her keys fall onto the grey step and she says fuck again. Simultaneously, her bicycle, which has been resting against the wall beside us, topples to the ground. She walks over to pick it up as I unlock the door and go inside.

The air is wooden and musty. Anna comes through the door behind me with a squeezed smile. She is wearing a summer dress of pastel blue cotton dotted with pale yellow flowers. A thin layer of sweat glows on the freckled skin above her breasts, soft as moons. With my index finger I flick the switches one by one. The strip lights in the small office strobe.

There are five desks inside, all hooked up to phones. I weave through them to the far side of the garage, turning right into the kitchen. The kettle is already full and I press it, lifting two mugs from the drying rack. The toilet perches in the corner of the narrow room, topped by rolls of pink paper. Someone has left a half-finished cigarette on the tank that has stained the ceramic. The kettle’s scaly deposits crackle faintly as I open the door of the fridge.

Fresh milk? No.

When I come out of the kitchen Anna is already on the phone, talking softly to someone in the voice that she uses for boys. Perhaps she left him slumbering in her wide, low bed this morning, the smell of her sex on the pillow. She has opened up the wooden doors of the garage so that daylight has filled the room. I hear the kettle click. Anna catches me looking at her and swivels her chair so that she is facing out onto the mews. I light a cigarette, my last one, and wonder who he is.

‘So,’ she says to him, her voice a naughty grin, ‘what are you going to do today?’ A pause. ‘Oh, Bill, you’re so lazy…’

She likes his being lazy, she approves of it.

‘Okay, that sounds good. Mmmm. I’ll be finished here at six, maybe earlier if Nik lets me go.’

She turns and sees that I am still watching her.

‘Just Alec. Yeah. Yeah. That’s right.’

Her voice drops as she says this. He knows all about what happened between us. She must have told him everything.

‘Well, they’ll be here in a minute. Okay. See you later. Bye.’

She turns back into the room and hangs up the phone.

‘New boyfriend?’

‘Sorry?’ Standing up, she passes me on her way into the kitchen. I hear her open the door of the fridge, the minute electric buzz of its bright white light, the soft plastic suck of its closing.

‘Nothing,’ I say, raising my voice so that she can hear me. ‘I just said, is that your new boyfriend?’

‘No, it was yours,’ she says, coming out again. ‘I’m going to buy some milk.’

As she leaves, a telephone rings in the unhoovered office, but I let the answering machine pick it up. Anna’s footsteps clip away along the cobbles and a car starts up in the mews. I step outside.

Des, the next-door neighbour, is buckled into his magnesium E-type Jag, revving the engine. Des always wears loose black suits and shirts with a sheen, his long silver hair tied back in a ponytail. None of us has ever been able to work out what Des does for a living. He could be an architect, a film producer, the owner of a chain of restaurants. It’s impossible to tell just by looking into the windows of his house, which reveal expensive sofas, a wide-screen television, plenty of computer hardware, and, right at the back of the sleek white kitchen, an industrial-size espresso machine. On the rare occasions when Des speaks to anyone in the CEBDO office, it is to complain about excessive noise or car-parking violations. Otherwise, he is an unknown quantity.

Nik shuffles his shabby walk down the mews just as Des is sliding out of it in his low-slung, antique fuck machine. I go back inside and look busy. Nik comes through the open door and glances up at me, still moving forward. He is a small man.

‘Morning, Alec. How are we today? Ready for a hard day’s work?’

‘Morning, Nik.’

He swings his briefcase up onto his desk and wraps his old leather jacket around the back of the chair.

‘Do you have a cup of coffee for me?’

Nik is a bully and, like all bullies, sees everything in terms of power. Who is threatening me; whom can I threaten? To suffocate the constant nag of his insecurity he must make others feel uncomfortable. I say, ‘Funnily enough, I don’t. The batteries are low on my ESP this morning, and I didn’t know exactly when you’d be arriving.’

‘You being funny with me today, Alec? You feeling confident or something?’

He doesn’t look at me while he says this. He just shuffles things on his desk.

‘I’ll get you a coffee, Nik.’

‘Thank you.’

So I find myself back in the kitchen, reboiling the kettle. And it is only when I am crouched on the floor, peering into the fridge, that I remember Anna has gone out to buy milk. On the middle shelf, a hardened chunk of overly yellow butter wrapped in torn gold foil is slowly being scarfed by mould.

‘We don’t have any milk,’ I call out. ‘Anna’s gone out to get some.’

There’s no answer, of course.

I put my head around the door of the kitchen and say to Nik, ‘I said there’s no milk. Anna’s gone–‘

‘I hear you. I hear you. Don’t be panicking about it.’

I ache to tell him about SIS, to see the look on his cheap, corrupted face. Hey, Nik, you’re twice my age and this is all you’ve been able to come up with: a low-rent, dry-rot garage in Paddington, flogging lies and phony advertising space to your own countrymen. That’s the extent of your life’s work. A few phones, a fax machine, and three secondhand computers running on outdated software. That’s what you have to show for yourself. That’s all you are. I’m twenty-four, and I’m being recruited by the Secret Intelligence Service.

It is five o’clock in the afternoon in Brno, one hour ahead of London. I am talking to a Mr Klemke, the managing director of a firm of building contractors with ambitions to move into western Europe.

‘Particularly France,’ he says.

‘Well, then I think our publication would be perfect for you, sir.’

‘Publicsation? I’m sorry. This word.’

‘Our publication, our magazine. The Central European Business Review. It’s published every three months and has a circulation of four hundred thousand copies worldwide.’

‘Yes, yes. And this is new magazine, printed in London?’

Anna, back from a long lunch, sticks a Post-it note on the desk in front of me. Scrawled in girly swirls she has written, ‘Saul rang. Coming here later.’

‘That’s correct,’ I tell Klemke. ‘Printed here in London and distributed worldwide. Four hundred thousand copies.’

Nik is looking at me.

‘And, Mr Mills, who is the publisher of this magazine? Is it yourself?’

‘No, sir. I am one of our advertising executives.’

‘I see.’

I envision him as large and rotund, a benign Robert Maxwell. I envision them all as benign Robert Maxwells.

‘And you want me to advertise, is that what you are asking?’

‘I think it would be in your interest, particularly if you are looking to expand into western Europe.’

‘Yes, particularly France.’

‘France.’

‘And you have still not told me who is publishing this magazine in London. The name of person who is editor.’

Nik has started reading the sports pages of The Independent.

‘It’s a Mr Jarolmek.’

He folds one side of the newspaper down with a sudden crisp rattle, alarmed.

Silence in Brno.

‘Can you say this name again, please?’

‘Jarolmek.’

I look directly at Nik, eyebrows raised, and spell out J-a-r-o-l-m-e-k with great slowness and clarity down the phone. Klemke may yet bite.

‘I know this man.’

‘Oh, you do?’

Trouble.

‘Yes. My brother, of my wife, he is a businessman also. In the past he has published with this Mr Jarolmek.’

‘In the Central European Business Review?’

‘If this is what you are calling this now.’

‘It’s always been called that.’

Nik puts down the paper, pushes his chair out behind him, and stands up. He walks over to my desk and perches on it. Watching me. And there, on the other side of the mews, is Saul, leaning coolly against the wall smoking a cigarette like a private investigator. I have no idea how long he has been standing there. Something heavy falls over in Klemke’s office.

‘Well, it’s a small world,’ I say, gesturing to Saul to come in. Anna is grinning as she dials a number on her telephone. Long brown slender arms.

‘It is my belief that Jarolmek is a robber and a con man.’

‘I’m sorry, uh, I’m sorry, why…why do you feel that?’

A quizzical look from Nik, perched there. Saul now coming in through the door.

‘My brother paid a large sum of money to your organization two separate times–‘

Don’t let him finish.

‘–And he didn’t receive a copy of the magazine? Or experience any feedback from his advertisement?’

‘Mr Mills, do not interrupt me. I have something I want to say to you and I do not wish to be interrupted.’

‘I’m sorry. Do go on.’

‘Yes, I will go on. I will go on. My brother then met with a British diplomat in Prague at a function dinner who had not heard of your publication.’

‘Really?’

‘And when he goes to look it up, it is not listed in any of our documentation here in Czech Republic. How do you explain this?’

‘There must be some misunderstanding.’

Nik stands up and spits, ‘What the fuck is going on?’ in an audible whisper. He presses the loudspeaker button on my telephone and Klemke’s riled gravelly voice echoes out into the room.

‘Misunderstanding? No, I don’t believe it is. You are a fraud. My brother of my wife has made inquiries into your circulation and it appears that you do not sell as widely as you say. You are lying to people in Europe and making promises. My brother was going to report you. And now I will do the same.’

Nik stabs the button again and pulls the receiver out of my hand.