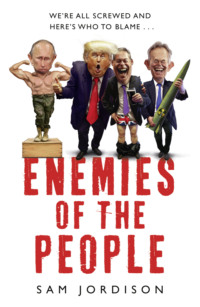

Enemies of the People

But Friedman still insists on the primacy of markets, describing them as a kind of perfect system that will correct and control themselves just so long as they are left well enough alone. He doesn’t allow for the fact that consumers don’t always have a choice. Or that sellers will often cheat those consumers.

Friedman’s thinking has led to market structures being imposed in all sorts of ways that they shouldn’t. He spread the belief that competition will magically make the education sector more efficient, instead of turning a public service into another place where shareholders get to soak us. He taught that private providers should control our health systems. His followers decided power companies with confusing tariff plans and ever richer owners are somehow better than nationalised utilities. His close personal friends in the George W. Bush administration – like Secretary of Defence Donald Rumsfeld – were even convinced that private security firms like Halliburton should carry out all kinds of security and administrative work in war zones like Iraq. Which worked out just fine …

It’s terrifying to go back to the source material and see the specious nature of the writing that has had such influence on our lives. There’s plenty more where that pencil theory came from. In Free to Choose, Friedman asks in all earnest how it was that Britain managed to expand its economy even more successfully than the USA in the late nineteenth century, given that Britain didn’t have comparable land and mineral resources? He answers even more seriously that it’s because Britain had a small government and free-market economic policy. He doesn’t mention the country’s huge coal reserves. Or, even more astonishingly, the fact that it had an empire on which the sun never set. Elsewhere, he just makes things up; especially in his many extrapolations about life in the Soviet Union, for which he can’t have had reliable data. But still, millions of people bought the absurd book. It was the non-fiction bestseller in the USA in 1980 and right-wing politicians lapped it up.

And Friedman didn’t just comment on economics; he actively proselytised. He called himself a ‘warrior’, determined to eliminate ‘government interference in free enterprise, from minimum wage to social welfare programmes’. He loathed nearly all the workings of the state and said that the ‘invisible guiding hand’ of the free market should ‘hold the tiller’ instead of any government.

His advocacy bore fruit when the UK Conservative Party was elected to power in 1979. He told the Washington Post that Thatcher’s election would ‘mark the turning away from the welfare state back to the free-market economies of the nineteenth century’. Correctly.

I know all that sounds like a nightmare – unless you like your chimney cleaned by sooty six-year-olds – but Friedman loved the Victorians. He also liked to claim the lack of regulation in the nineteenth- and early-twentieth-century markets did more to improve the life of the common man than at any other time. Incorrectly.

And Friedman was soon jetting off to meet the new prime minister and persuade her to make things more Dickensian. She told him she would be delighted to do just that, so he wrote a Newsweek column entitled ‘Hooray for Margaret Thatcher’.

Back home in the USA he was also soon serving as a member of President Reagan’s Economic Advisory Board. He persuaded Reagan that there was a ‘natural rate’ of unemployment and that having a few million people out of work was probably a good way to stop stagflation. So Reagan made sure unemployment hit record highs for years.

There was also Chile. Friedman’s acolytes from the Chicago School had been there, right alongside the military, in 11 September 1973 when Pinochet overthrew the popular government of Salvador Allende in a bloody coup. Immediately after, the ‘Chicago Boys’ put into practice the teachings of Friedman’s other famous book, Capitalism and Freedom. As Pinochet began torturing and killing tens of thousands of his people, the economists started tearing apart Chile’s industry, privatising, throwing the markets open, destroying local workers with free trade, overseeing 375 per cent rises in inflation and claiming that the problem was that their economic medicine hadn’t been strong enough.

Pinochet was soon getting a bad international reputation for rounding people up and shooting them in football stadiums – but still Friedman himself came down to help in 1975, meeting Pinochet, broadcasting lectures on national TV, asking for his usual formula of deregulation and ‘shock treatment’. He wrote in his diaries that Pinochet (although a mass murderer) was worried about the social consequences of rising unemployment. Friedman told him to cut government spending by another 25 per cent. That’s right. Where even Pinochet had qualms, Friedman had none. And so millions lost their jobs. The economy didn’t recover for almost a decade, when Pinochet at last changed course. Friedman later falsely claimed that Pinochet’s adaptation of free-market policies ameliorated his rule and led to the country’s transition to democratic government in 1990 … After almost twenty years of tyranny and the torture and murder of thousands. But hey! At least the invisible hand of the market determined which brand of cattle prod the police used to electrocute people.

Now you can get angry.

Pinochet is fading into bad memory. Chile is moving on. But many of Friedman’s other legacies remain with us. Closer to home, you can still blame Friedman for the privatised electricity companies and their huge bills. Blame him if you’ve heard a Republican politician talking with loathing of ‘big government’. If you’ve lamented paying so damn much to catch a privatised train service, Friedman’s at the heart of it.

On a broader level, his ideas provided ideological cover for massive capital accumulation for multinational corporations during the 1980s to 2000s and the belief that markets should be regulated as little as possible. On Friedman’s death in 2006, President George W. Bush said, ‘His work demonstrated that free markets are the great engines of economic development.’ Two years later those engines started grinding and chucking out black smoke. Friedman had missed the 2008 financial crash his ideas helped bring about – and which proved them so catastrophically wrong. Oh well.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.

Вы ознакомились с фрагментом книги.

Для бесплатного чтения открыта только часть текста.

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера:

Всего 10 форматов