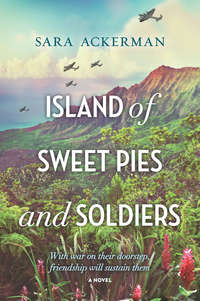

Island Of Sweet Pies And Soldiers: A powerful story of loss and love

Within minutes, her friend stood in the living room with her arms wrapped around Violet. “It will be all right, Violet, I promise you.”

“Did you see him after school?” Violet asked.

“No, I went straight to Japanese school. I didn’t get back until five, just before Ella showed up on my porch.”

Footsteps announced a visitor, and Luther appeared at the door. A veteran of the Great War, he’d arrived in Honoka’a eight years earlier to take over the position as shop teacher and unofficial handyman. Deaf in one ear, and the size of a bear, he and Herman became fast friends. Luther had lost a nephew at Pearl Harbor and had been drowning his sorrows in the bottle, which worried Violet since he had no wife and no other family around.

Overnight, Luther’s face had turned ashen and his clothes crumpled. “Any news?” he asked.

She repeated the sheriff’s update and added, “Herman drove out there without telling anyone, which concerns me. He didn’t mention anything to you?”

“Nope. I’ve been up most of the night thinking on it. Would it be possible he was meeting someone to fetch a new batch of okolehao?”

“He would have mentioned it. Plus, he still has a few bottles left,” she said.

“Yes, but you know how much it’s worth these days, now that everything’s being rationed. We both know he’s a shrewd businessman.”

True. Okolehao was a Hawaiian ti-root moonshine, but some of the locals also used pineapple, taro, sugarcane or rice. Just up the road, Waipio Valley had become a hotbed of illegal okolehao production during Prohibition. Violet hated the stuff.

“I feel like he would have told me. But I suppose it’s possible.”

She wanted to believe him, and wondered if Herman had gone down into the valley to meet someone. There was a Hawaiian man down there he had mentioned once or twice. And maybe the river had overflowed and he was stuck down there. It made sense and was about the only thing that could possibly, remotely, hopefully have been true. But truth, she was finding, didn’t always want to be known.

“I’m heading over now to talk to the sheriff,” he said.

Violet dropped down on the cracked red paint of the front step. She watched him walk away. Unable to do anything else, she lay back and let the tears come. Setsuko sat next to her and held her hand while she went numb from the inside out.

* * *

Just before lunchtime that day, Ella called out, “Mama?”

Violet rushed to the pune’e. “Good morning, love. How you feelin’?”

There was a new vacancy in Ella’s eyes, like someone had taken an eraser and removed all the brightness, leaving a dull brown. Ella didn’t answer, just closed her eyes and rolled to face the wall.

Setsuko had slipped on an apron and said from the kitchen, “Ella, I have your favorite. Rice cakes.”

Violet began to wonder if Ella’s condition might not be a sickness at all. The timing was peculiar. Disease is in the mind, her father used to say, never allowing anyone to skip chores because of a sniffle or miss school due to a burning throat. As though you could think yourself well. Was it possible that we could also think ourselves sick? Violet reminded herself that Ella had been playing at the Codys’, so what could she possibly know?

“Did you happen to see Daddy yesterday afternoon? Before he drove off.” Ella shook her head. “Did he say anything to you at all yesterday about going someplace in the afternoon?”

In the silence between them, her fear began to spread.

“Honey, I need you to talk to me.”

“My tummy hurts,” Ella whispered.

“Setsuko, would you mind fixing some poi?”

A voice inside was telling Violet that the two incidents were connected. Her tough little girl suddenly seemed so fragile. “Where were you when the other kids were looking for you?”

“I had a good hiding place. I told you that,” Ella said.

Violet watched the rise and fall of her ribs. Tenderness rushed through her.

“Sometimes, when you hold things inside, it can make you feel sick. Is that what’s happening?”

Ella shook her head again, limply.

Violet let out a big sigh. “We can keep it just between you and me, but I need you to tell me anything that seemed out of the ordinary. Even if you don’t think it matters.”

“There’s nothing to tell.”

She prodded Ella for more information, but Ella refused to answer. Frustration was building up inside, causing every cell in her body to hurt. She wanted to scream.

* * *

When Sheriff Souza returned, his face had bad news written all over it. He didn’t waver as he asked her to accompany him into the kitchen and swung the door shut. Her heart dropped.

He chewed on his lower lip for a moment before speaking. “Now, I can’t say that we found anything conclusive, and there was plenty of rain last night, but we combed the area around his car and there appear to be some broken bushes. And blood. Just a small amount, but it was near the edge of the overlook.”

The word blood was all she heard. “Did you look below? Could he have been hurt and fallen?”

She pictured the cliffs. Lofty, vertical slabs that plunged straight into the roiling blue. In some areas, small outcroppings of land jutted out.

“Anyone falls, they end up in the water. Or on the rocks. We didn’t see a body on the rocks.”

A body. She felt herself unraveling at the seams and had to check to make sure her upper half was still connected to her lower half. Strangely, she felt as though she were listening to a radio detective show. Herman dead was impossible. Husbands were not allowed to die. Especially young ones. Especially hers.

The words came out in a whisper. “Luther thinks Herman went into Waipio with someone for okolehao. That blood could have been from anything, couldn’t it? A pig, a goat.”

“Could have been. I sent Boy Rapozo down to check. No one coughs down there without him knowing about it. Gonna have the blood tested. Do you know his type?”

“O.”

The ringing in her ears ramped up and Violet focused on Souza’s bristly mustache and the way his lips jutted out underneath. How his gaze moved around the kitchen, trying to find an anchor.

“Thank you, Sheriff.”

“We’ll get to the bottom of this. People don’t just disappear in Honoka’a. Not on my watch.”

As it turned out, they did. The only lead that turned up was from a chicken farmer up the way who claimed he heard two gunshots that afternoon. But even he couldn’t be sure from which direction they had come. Speculation in town was rampant. Herman worked for the Japanese. A moonshine deal had soured. He was gambling on cockfights. Working for the FBI.

That people thought someone as upstanding and well liked as Herman could be a spy boiled her insides. But she had to admit most things Japanese did have a special place in his heart. His secretary was Japanese, he boasted that some of his best teachers were Japanese, and many of his friends were Japanese. He liked Japanese food, drank Japanese wine, and grew Japanese sweet potatoes in his garden. But did that make him a spy?

Violet swayed back and forth between her own two theories. One was that he might have been on watch for the Hawaii Rifles, and been ambushed by the Japanese while out patrolling along the cliffs. But no one else had seen anything suspicious and no one else had up and vanished. The other idea was that he had upset someone in the spirit business, because he had on several occasions voiced an interest in making his own. She had argued against it.

“How will it look if the school principal is also a moonshine distributor?” she had said.

“Honey, it would just be for a few of us around here. And we could use the extra money to buy more land.”

“Not a good idea,” she’d insisted.

If only she could find his calendar, which he also used as a sort of journal. It was not on his desk where it usually was and had yet to turn up. Either he had it with him, or someone took it. This was the one piece of information that didn’t fit. How could someone have taken it? Sheriff Souza had interrogated everyone in the school on this small fact, reasoning that if someone had taken the journal, someone had access to his office.

For an entire week, Ella wouldn’t eat solid food and Violet took to feeding her spoonfuls of chicken broth and rice. She refused to go back to school, and so Violet had to bring her to class once she returned to work the following week. There was no way for Violet to hide the swollen redness of her eyes, so she didn’t even bother. Sleep came sparingly. By mornings, her pillow was soaking and covered in clumps of hair. Herman, where are you? As best she could, Violet tried to stay in that slice of time just after waking, before she remembered. It never lasted more than three seconds.

Eventually, the blood results came back. Human. Type O.

Chapter Five

Violet

The next day at school passed without incident, and Violet met Ella at her class. They stopped at home for a quick snack of chocolate pudding, then continued across the worm-eaten bridge over the ravine and up the hill to the small building where Japanese school was held. They passed clumps of ginger, a thick stand of guava clouded with fruit flies and a dilapidated chicken coop with rusted wires, full of vines instead of chickens. Ella held her hand like she was trying to strangle it.

Before Pearl Harbor happened, students learned to speak the Japanese language, practiced calligraphy, and were schooled in common traditions like ikebana and yukata. Violet guarded her opinions, but she thought it a miracle the school had been allowed to keep on. The military had ordered Takeo to stick to arts and crafts. None of the kids minded.

Please, God, let this work out. Umi and Hiro already knew about Ella coming, but there was concern over how her presence would go over with the other students. Takeo had said, “Do not worry.” But worry was everywhere, as plentiful as the stalks of sugarcane in the fields. The elongated one-room building contained two sections, and Ella would be with the six-to twelve-year-olds.

When they approached the school, Ella stopped. “Do you think they will like me?”

“You already know most of the kids.”

“That’s what I’m worried about.”

The words tugged at Violet’s heart. “The sensei is like your uncle, so no one will dare bother you.”

Even before Herman’s disappearance, Ella had been shy and considered different by the kids. Partly because of her skin color, but more than that, she was the kid in the group who chose green when everyone else chose blue. She picked animals over people, and once punched Robbie Iwase in the nose when he tried to torture the class rabbit. From then on, kids steered clear.

They stood there, staring at the whitewashed wooden house. Two mynah birds chattered on the road in front of them. Ella looked around, and Violet followed her gaze.

In front of the schoolhouse, a row of garden boxes overflowed with lettuce, kale, plump tomatoes and eggplant. Off to the side a large square patch of sweet potato crawled through the grass. The students had painted VICTORY in red, white and blue on the boxes, which might have helped their cause. Several fat hens scratched about, reminding Violet of home. Leaving her hens had been one of the hardest parts about leaving Minnesota. On the sagging plank porch, two girls played jacks, too engrossed to notice them.

Ella tugged at her hand, and together they crossed the yard and entered the building. There were no desks, no tables and chairs, only tatami mats spread out across the floors. The walls were lined with shelves and everything had a place. The sills were painted a deep red and several bonsai plants caught sun through the mottled glass. Violet felt a stab of envy. Her classroom had never looked so tidy.

The chatter of young voices filled the room, and Takeo stood near the front. In the other half of the house, Setsuko taught the teenagers. After the war broke out, the school lost many students, parents fearing to seem overly Japanese. Though how could you be anything other than Japanese, if you were Japanese? She had yet to determine exactly what constituted one’s Japanese-ness, but being born in Japan was at the top of the list. Takeo and Setsuko had destroyed, or possibly hidden, all photos of their family back in Japan, some of whom had been members of the Imperial Navy. The predicament caused an ache in the middle of Violet’s chest.

Little by little, voices quieted. Heads turned. Ella’s fingers curled around her hand more tightly, and Violet squeezed back. Takeo spotted them and hurried over. “Violet and Ella, welcome.”

“Thank you, Sensei,” Violet said, feeling safe to address him here, but certainly no place else.

“Are you going to stay?” he asked her.

“Should I?”

They both looked down at Ella, who was staring at the back corner of the room. Giant origami butterflies and cranes, fish and frogs hung from the ceiling. “Sweet pea, would you like me to stay?”

At that very moment, Umi marched up and grabbed Ella’s hand, leading her to the back of the room. She pointed at the folded paper creatures, while her two long braids twisted down her back like origami snakes. Violet had been looking for some kind of sign. To tell her that life was ready to flip-flop. Maybe this was it. She took a chance and slipped out the side door.

* * *

The house felt strange without Ella, almost soulless. Violet had grown used to her always being underfoot, filling the cracks with her presence. Strange how you noticed something more once it was not there. In the kitchen, Jean was listening to the radio and grading math worksheets. She looked up and her lashes fluttered when Violet walked in.

“Don’t tell me she let you leave her there,” Jean said.

Violet had spent the half mile home wondering if she should go back. “I sneaked away while she was distracted.”

“Baby doll, that is wonderful!”

The throbbing in her feet from standing all day prompted her to sit. “Ella wishes she was Japanese, so it couldn’t be more perfect.”

Jean smiled. “I’m feeling hopeful. For Ella. For me. Even for you.”

“What’s that supposed to mean?”

“Just that Zach is here. More than anyone alive, he will take my mind off Bud. And things are now looking up for Ella, in which case you won’t be able to help but be happy.”

Jean and Bud met a month before the first batch of soldiers left town. He had ridden the school bus into Honoka’a with her students one morning and asked for directions to the theater as he climbed out. When the bell rang, she found him hovering outside her room. That was it for both of them. All his liberty time was spent holding tightly to Jean’s hand. Aside from being a marine, Bud was a grass-chewing, rough-riding Texan. He also liked to spit. Violet had put up with him for Jean’s sake.

If someone could stop Jean from ruminating about Bud, Violet would be eternally grateful. That kind of pining was not helpful. Sewing, movies, trips to the beach, nothing worked. She’d even involved Jean in their victory garden up the hill. And Jean had gotten her hands dirty for possibly the first time ever. But in the midst of harvesting, Jean said the cucumbers reminded her of Bud and alternated between sniffling and sobbing the whole time. Violet had her own thoughts about Bud but she kept them to herself. Mainly that he seemed interested in only one thing. She didn’t quite trust the man.

Violet reached across the table and squeezed Jean’s hand. “I hope you’re right.”

Happy was a word out of another lifetime. Sure, she no longer felt like she was living underwater with the whole ocean pressing down on her. Life had become tolerable.

“Even if I’m wrong, you still better love me forever,” Jean said.

Thank goodness Jean’s moods were catching. “You? Wrong?”

“Oh, by the way, Zach called and said he might come out this weekend. They’ll be on liberty. That fine with you?”

“You don’t need to ask. Just keep him away from Irene Ferreira or he’s a goner.”

Jean winked and stood up to check on the meat loaf in the oven. By now, the entire kitchen smelled like tangy sauce and sage. Wednesday was Jean’s night to cook, and she commandeered the kitchen. With rations, they’d had to get creative. Packing sardines into sushi or fashioning Spam into casserole.

Jean poured Violet a tall glass of passion orange juice. “In high school, he was a goofball with the ladies. Sweet as can be, but his tongue tied up in knots.”

“Just warn him,” Violet said.

Chapter Six

Ella

Why don’t they have us make origami animals in regular school? Instead, Mrs. Hicks forces us to make cardboard slippers and painted egg crates for the wounded soldiers. Everything is about the soldiers. Sometimes I wish they would just go away, even though we need them for protection. I wish we could just erase the war and erase the fact that now Japanese people are bad. Maybe the ones in Japan are different, but I like most of the ones here.

At home, Umi always folds miniature origami animals, and she tries to teach me, but mine come out ugly and smooshed. I thought it was because my fingertips are too big, but Umi says I need proper lessons and lots of practice. Any paper Umi gets her hands on ends up a tiny perfect creature. Now was my chance.

These origami in the classroom were huge enough to breathe on their own or fly away. I couldn’t wait to make Snowflake into a folded paper cat the first chance I got. Big fingertips wouldn’t matter with these.

When I finally remembered where I was and looked for Mama, she was gone. I felt the usual pinch of fear, but instead of rising into a panic, I got drawn into the singing at the start of class. Sensei, as he told me to call him, hit a small gong that made my teeth ring. Everyone was singing with their full hearts. They all knew the words. I had no choice but to sit with Umi, feeling dumb since I didn’t know the songs. Some of the other kids gave me weird looks and scooted away. But kids don’t worry me too much, especially singing ones.

I knew I might be lost learning a new language, but Japanese words seem easy to me. I already know some. Sensei, obake, satoimo and arigato were just some. We have an obake living in our house. It might even be Papa. The words have trickled down to Umi and Hiro from their parents. Sometimes I feel jealous, because they have a whole family. At night, I imagine that Papa will be home in the morning, cooking coffee and waiting to pick me up and kiss the ribbons in my hair. Whenever he hugged me, I ended up smelling like Old Spice afterward. I still have his bottle, and when I really miss him, I put a dab on my wrist before I go to bed.

Singing took up a lot of the time that day. And just when I thought we were finally going to stop, we started another song or sometimes repeated the same one forty-seven times. Itchi ni san shi. I was sneaking glances around me. The boy to the left had a string of snot dripping from his nose, but he kept singing. June Higa, right in front of me, swung her silky hair back and forth as she bobbed her head in time. All Japanese girls have nice hair. It must be a God-given right. And straight parts. I don’t even have a part.

After the singing, Mr. Hamasu, who no longer allows anyone to call him sensei, talked to us about plants, and how we were going to expand the victory garden to the other side of the building, which meant we would need to help clear the bushes away. Work clothes were required for next week. After that, we were going to grow our own bonsai plants! In honor of the soldiers, of course.

He told us, in his very even voice, “Bonsai plants are different than our garden plants because they’re for the mind, not the body. Caring for your own bonsai will teach you patience, ingenuity and focused effort. Some of them won’t survive, but that, too, is part of the process.”

He passed around several bonsai trees, which seemed old and wise. Hiro says that one at their house is over a hundred years old. He sometimes makes stuff up, or at least stretches out the truth, but this time I believed him.

By the time class ended, I knew I wanted to come back. Even if I heard one girl whisper to her friend, “What is Ella Iverson doing here? She’s haole.”

As if that were some kind of great revelation. Of course I was haole. I had always been haole. I would always be haole. “So, what’s the big deal?” I wanted to say.

It was easy to pretend they didn’t exist. I’d had practice.

Chapter Seven

Violet

When the shadows had lengthened and the thrushes broke into song, Setsuko and Umi showed up at the door with Ella. Violet had been checking the window every few minutes, watching for their arrival.

“Auntie Violet, your daughter is home!” they called.

She ran out to greet them. Ella walked straight to the coffee table and set down a folded red crane before coming back to hug her. The hug was double what she usually got.

“How did it go?” She eyed Setsuko, who smiled.

Waves of excitement were pouring off of Ella. “I’m going to make a bonsai, and help in the victory garden!”

Violet bent down, not wanting to tamper with her success by making too big a deal. “Well, that’s wonderful news. I’m sure they can use you with all of your gardening expertise.”

“They sing a lot, too. I don’t mind singing, but today I didn’t know the words.”

Setsuko risked a laugh. “The words will come.”

“Did you learn anything else?” Violet asked.

Ella thought about it for a while. “I learned that it’s a whole lot more fun than regular school.”

“Oh, honey, I’m happy you had a good time. You still have to go to regular school, but this will be something to look forward to.”

With Ella on the mend, their lives could take on a whole new orbit. She envisioned Ella plumping up, waking to dry sheets in the morning, not being terrified senseless by air-raid drills and letting her skin heal over. The hurts of her daughter commingled with her own, but instead of seeming double, they more than quadrupled. Certainly Violet missed Herman as a husband and the man she counted on in life, but more so she missed him as a father to Ella, as a fellow parent. Every now and then she felt guilty for having those feelings. That she should have loved him more passionately. But that was the truth, and lying to herself would serve no purpose.

* * *

On Thursday and Friday, Violet held her breath while Ella was at Japanese school, at any moment expecting to have her show up at the door. But on both days Ella returned with new stories and an extra spot of color on her cheeks.

“Today Sensei told us a story about Tanuki, and I want to get one,” Ella said, folding her hands on her chest like it had already been decided.

“A what?”

“Tah-noo-key.” Ella rolled her eyes and drew the word out as though speaking to a four-year-old. “A Japanese raccoon dog. He says they’re jolly and mischievous and some can even shape-shift into other animals.”

If Ella had it her way, they’d be collecting animals like most people collected stamps or coins. “Ask Umi to help you make an origami one for now. That’s about the best I can do.”

Their meager food rations and low wages were just enough to feed their own mouths, let alone a zoo. Sugar had been the first to be rationed and then came milk, butter, oil, meat, coffee, and other canned and processed foods. Thank goodness for their garden and those of nearby folks, with whom they often traded. Gasoline was another story. It wasn’t something you could grow. Most civilians got an A sticker, which entitled them to only three to four gallons a week, which couldn’t get you very far. Everyone stayed close to home.

* * *

When Saturday dawned a honey-colored sky, they piled into the Ford and drove up to their garden plot above town, in a place called Ahualoa. The road was steep in some places, rolling in others. Thickets of koa and smaller clusters of ohia attracted bees, and even native honeycreepers. Ella kept her eyes glued to the window, waiting to spot the tiny red birds darting from tree to tree like forest sprites.