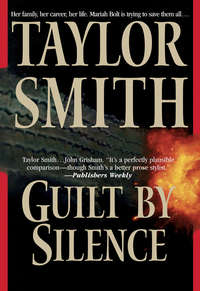

Guilt By Silence

He and Nancy exchanged glances and squeezed hands.

“I believe,” McCord went on, “that the sheer force of Nancy’s mother-love saw our sick children through their darkest hours. But sometimes, when a baby is born too soon, or with special problems, even a mother’s love needs a little help. This clinic is dedicated in ensuring that even the littlest ones like Jessica will survive and grow and thrive.”

There was a round of applause.

“I would ask my wife, Nancy, and Mary Boehm—two of the finest and most determined mothers I know,” McCord said, “to jointly do the honors of cutting the ribbon to open the McCord Neonatal Clinic.”

Mary Boehm’s surprise showed through her tears, but she quickly wiped them away as Gus stepped back. Nancy McCord moved beside her, offering a smile and a hug, and then handed Mrs. Boehm a pair of large surgical shears and held up the ribbon. Mary Boehm’s hand was trembling as she reached out and snipped the wide red sash. It fell to a cheer and a hearty round of applause.

Dieter Pflanz looked around the room and noted that several full-grown men were conspicuously swallowing lumps in their throats. There wasn’t a dry eye in the place. For a fleeting second, he felt the instinctive bristle rise up his spine as the crowd rushed forward to surround McCord, but then he relaxed again. It was obvious that there was nothing but goodwill toward Gus McCord in that room.

Watching the milling crowd, scanning those who were approaching McCord from all sides, Pflanz paid little attention to Jerry Siddon, who had moved next to him.

“That was a neat trick, wasn’t it?” Siddon said.

Pflanz glanced down at him. “A neat trick?”

Siddon waved his hand toward McCord. “That performance,” he said, grinning. “And turning the ceremony over to the baby’s mother. Focusing the attention on himself by seeming to turn it on someone else. Very neatly done.”

Pflanz arched one eyebrow. “You’re very cynical today, young Siddon.”

“Not cynical, just overawed at the man’s skill.” He glanced up at Pflanz, who was watching him closely. “You know what I mean. This guy’s tough as nails. You know it, and so do I. That’s how he made his fortune and his name. But look at him now.”

They both turned back to McCord, who was guffawing with a group of old cronies, his hands buried deep in his pants pockets.

“He looks like he just drove in from the farm in the family pickup,” Siddon continued. “Yet this is the same man who, in a few hours, will be standing toe-to-toe with the sharks and vultures in Washington. The man who may have done more than any other American to throw the Reds out of the Kremlin. I tell you, Dieter, this is the one. This is the guy we’ve got to put in the White House. He’s the one who can make things happen.”

The corners of Pflanz’s mouth angled up ever so slightly. He doesn’t need to be elected, Jerry boy, he thought. Things are happening already.

When Frank’s secretary tapped on her door a few minutes after she had stormed out of his office, Mariah was standing at the window, staring down on Langley Woods situated beyond the high fence surrounding the Agency’s headquarters.

“Mariah?” Pat hesitated, her hand on the door. Finally, she stepped in and shut it behind her. “What happened? Frank’s in there bellowing on the phone and you look like you’ve seen a ghost. What’s going on around here?”

Mariah glanced at Pat and then stared back across the trees, denuded now of their leaves. It was a bleak landscape this time of year.

Tucker’s secretary was one of her closest friends, as was Frank himself. But Patty Bonelli and Frank were also an item—undeclared, discreet. It was a relationship that only Mariah and a few others in the office knew about. Mariah wasn’t altogether certain when Pat and Frank’s relationship outside the office had begun—for the first few years after his wife died, Frank had been too preoccupied with finishing the job of raising his kids to have time for anything else—but it had been going on for some time now. They seemed to be comfortable with it just as it was, neither one showing any sign of needing or wanting a more public commitment.

There was no way of knowing whether Pat was aware of the covert operation Frank had alluded to. As a senior secretary, she was privy to many of the compartmented cases that Frank and Mariah had worked on in the past, providing clerical support. But Frank had said that Operations was leading on this, and they always kept knowledge of their files to a minimum. If they had allowed Tucker in, it could only be because they had required his expertise. It was doubtful Pat knew anything, even if she were prepared to defy Frank and tell Mariah. On the other hand, Mariah thought, if Chaney had stumbled onto something, then it wasn’t as closely held a secret as Frank thought.

“Do you know if Frank has been working on any major cases with the Ops people over the past ten months?”

“He and George Neville have been working on a file,” Pat said. Neville was the CIA deputy director for operations—DDO. “I’m not cleared for it, though. I thought you were.”

“Why did you think that?”

“Because Neville was in Frank’s office the other day. Frank asked me to bring them coffee and when I opened the door, I heard Neville mention your name.”

“What was he saying?”

Pat shook her head. “He clammed up when I walked in. What’s this about, Mariah?”

“That’s what I’d like to know. I think it’s got something to do with the accident in Vienna.”

“What do you mean?”

“Apparently, it was no accident.”

“What?”

Mariah sighed and settled down on the edge of her desk. “Look, Patty, I don’t know what’s going on, but I shouldn’t be saying anything. You know Frank—he’d throw a fit if he knew I’d told you this much, so do me a favor and don’t mention it, okay?”

“I won’t say anything. But what do you plan to do?”

Mariah turned back to the window. “I don’t know. But I have to find out what really happened.”

With Frank or without him, she thought.

When Pat left her office, Mariah stood at the window a few minutes longer, struggling against the pain and black fury that were threatening to short-circuit her brain. Forcing herself to turn away from the window, she caught sight of the computer terminal next to her desk. She sat down and flicked it on, her mind racing as the monitor raised its greenish glow.

After a short delay, the screen prompted her to enter her password, the first line of defense against unauthorized access to the Agency’s data banks. All employees had a personal access code, known only to themselves and the computer. Security procedures required that the password be changed every month.

Mariah punched in her current personal code— “SIGMUND,” the name of her neighbor’s cat. After the mess she had found in her tiny garden, the feline had been on her mind the last time she had changed her password. The cursor moved across the screen as she entered the cat’s name, but only Xs appeared—another security measure.

After a brief delay, the monitor flashed a message: “PASSWORD VALID. FILE SEARCH MODE. ENTER FILE NAME.”

She returned her gaze to the keyboard and punched in “CHAUCER.”

There was another short delay. Her stomach flipped when she saw the reply: “RESTRICTED FILE. ACCESS DENIED. ENTER NEW FILE NAME.”

“Access denied, my foot!” she muttered. “That’s my file.”

She punched in her password again: “CHAUCER.”

“RESTRICTED FILE. ACCESS DENIED. ENTER NEW FILE NAME.”

Her heart was pounding as she leaned back in her chair and stared at the stubborn message. Then she hunched forward again. “All right,” she said under her breath, “let’s try another approach.”

She punched in a new file request: “MARIAH BOLT. PERSONAL LOG. VIENNA STATION.”

The cursor flashed for a moment as the Cray computer down in the Agency’s basement searched its data banks. Then a long list of document titles began scrolling down the screen—three years’ worth of contact reports and intelligence assessments that she had filed while she was posted to the CIA station in Vienna. As her eye scanned the rolling list, Mariah’s mind wandered back.

It was never a given that she would get an overseas assignment.

Despite its monolithic appearance, the CIA is a bureaucracy like any other, with internal divisions and rivalries. The most pronounced is between its operations (DDO) and analysis (DDI) directorates. Operations officers do the overseas clandestine work, while back at Langley, analysts sift through masses of intelligence garnered from various sources like tea-leaf readers, trying to predict the future. These two sides of the house view each other with mutual suspicion bordering on contempt. The trained covert operators regard the analysts as ineffectual pencil pushers, shuffling papers and conducting endless intellectual debates while the world burns around them. To the analysts, the clandestine ops people are cowboys, too often launching risky and ill-conceived operations that end up backfiring and smearing the Agency’s reputation. Limited interplay between these two directorates only feeds the skepticism and distrust between them.

Mariah had made her career among the analysts. Frank had recruited her because of her specialized knowledge of the Soviet arsenal, and for ten years she had helped track political and military developments in the Soviet Union. She had worked on various desks, sifting through intercepted communications for hints of what the Soviets were planning next, poring over the satellite photographs of secret installations, interpreting whatever gossip could be gleaned on who was up and who was out in the Moscow hierarchy. On a couple of occasions, under State Department cover, she had attended Soviet-American conferences posing as an administrative aide, meeting the faces behind the names in the intelligence reports and trying to figure out if there were moderates on the other side who would work for an end to the craziness.

During this time, David had been building a name for himself as a brilliant theoretician as well as a thoughtful writer on the need to contain the atomic beast that the scientists at Los Alamos had unleashed in 1945. When the Soviet Union had first begun to show signs of disintegration, he and Mariah had both worried about the danger of its nuclear arsenal slipping away in the confusion. David had developed a friendship with Hans Blix, the Swedish director general of the International Atomic Energy Agency, the U.N.’s nuclear watchdog. When Blix asked David to come to Vienna to help with the job of beefing up the IAEA, he was eager to accept.

Mariah had talked it over with Frank and he, in turn, had gone to DDO, George Neville. In the end, they had agreed to transfer Mariah to the operations side of the Agency and post her to the Vienna station under cover of the embassy’s administrative section. For the period of the Vienna assignment, Mariah—somewhat to her chagrin—had joined the cowboys.

The list of titles on the screen ended with a reference to the last contact report she had filed in Vienna. It was a brief account of her secret meeting with the Hungarian diplomat she had raced off to see instead of driving Lindsay to school that terrible morning.

She fumed at the sight of his code name on the screen— “RELIANCE”—someone’s idea of a joke, it seemed. The man was an alcoholic and a completely unreliable asset. He had been run by the Company for years, far beyond his capacity to provide anything useful by way of information on the crumbling Soviet empire in Eastern Europe. For this bum, I sent my family into a trap, Mariah thought bitterly.

But what she was looking for as she scanned the names of reports was “CHAUCER”—the code name of the Russian physicist who had confided her suspicion that Soviet nuclear weapons were being traded for hard currency. Mariah had met her through David’s office, had recruited her, had been her handler right up to the day the woman disappeared.

Tatyana Baranova was serving in the multinational IAEA when Mariah first encountered her at an agency farewell party for a departing British inspector. Lindsay was there, too, Mariah suddenly remembered with a smile. In fact, truth be told, it was Lindsay who had opened the door to the CHAUCER operation.

She had picked Lindsay up from the American School, and the two of them had run up to David’s IAEA office in the Vienna International Centre on the Wagramerstrasse. There they had found an office party in full swing.

Someone had placed a glass of wine in Mariah’s hand and a soft drink in Lindsay’s, and the two of them were sitting perched on a desk in a corner, laughing at David playing his harmonica and the impromptu chorus serenading the retiring British inspector with an off-key and tragicomic rendition of the Beatles’ “Yesterday.” When the song ended, half of the chorus was on bended knee, arms wrapped around the legs of the laughing Brit, imploring him to stay. Lindsay giggled at the silliness as the inspector turned several shades of red, struggling in vain to detach himself from the grip of the clowns at his feet.

“What a beautiful child!”

Mariah turned away from the antics across the room and found herself facing a woman who was watching Lindsay, bewitched, it seemed, by the copper curls and laughing dark eyes. She had apparently sidled up next to them at some point during the song. She looked to be in her early thirties, a few years younger than Mariah herself, short and on the pudgy side—the typical result of a starchy East European diet. She had a round, pleasant face and wide-set, pale blue eyes under overpermed blond hair. Her smile, as she glanced over Lindsay’s head at Mariah, was the hesitant gesture of the shy and lonely. The eyes dropped quickly, back to the child.

Lindsay looked up, a flicker of self-consciousness crossing her features before the giggles overtook her again. “That’s my dad,” she said, pointing at the group across the room. “He’s so crazy!”

The woman smiled once more, her eyebrows rising as she followed Lindsay’s finger. “Which one? Mr. Hewlett, who is leaving us?”

“No, the one with the harmonica. He’s a really good player. He taught himself. He can play anything, but he likes the blues best,” she confided.

“Oh, I see. So you are Dr. Tardiff’s little girl. What is your name, sweetheart?”

“Lindsay Bolt-Tardiff,” Lindsay said, holding out her hand, very grown-up. “And I’m eleven—well, almost.” They shook hands.

“Please excuse me,” the woman said, her expression appropriately serious. “I meant to say ‘Dr. Tardiff’s fine young lady.’ I am very pleased to meet you, Lindsay Bolt-Tardiff. I am Tatyana Baranova—you must call me Tanya.”

“Hi.” Lindsay glanced back at Mariah. “This is my mom.”

“Mrs. Tardiff. How do you do? You have a beautiful daughter.”

“Thank you,” Mariah said, smiling as she took the woman’s hand. “Call me Mariah. Do you work with the IAEA, Tanya?”

“Yes, but I have only been here a few weeks. I do not know many of my colleagues yet.”

“How are you finding Vienna?”

“It is very beautiful. Very expensive,” she added, rolling her eyes. “There are so many things in the shops—my goodness, I can hardly believe it—but not many bargains.”

“That’s for sure.”

“In Moscow, the shops have nothing. Here, it is the opposite, but expensive! How simple people live, I cannot imagine.”

“There’s a lot to see and do that doesn’t cost a fortune, once you find your way around.”

“I’ve seen the Lippizaner stallions three times!” Lindsay proclaimed proudly. “They dance!”

Tanya smiled warmly at her. “Just like your eyes, lovely one. Tell me, where did you get your beautiful hair? Your papa’s is black and your mama is fair, but you—so beautiful, this hair!” She ran her fingers lightly across Lindsay’s curls.

“I don’t know. Daddy says I’m a throwaway.”

“Throwback, Lins,” Mariah said, laughing. She looked up at Tanya. “My grandfather had red hair. I’ve never met a redhead in David’s family, but he says there were a few somewhere on the family tree, so I guess he must be carrying the gene, too.”

“Why would Daddy carry his jeans? And what’s that got to do with hair, silly?”

“Not jeans—genes. G-E-N-E-S,” Mariah explained, spelling out the word. “The kind you inherit from your mother and father that determine if you’ll be big or small—have brown eyes or blue. Red hair is uncommon because the gene is recessive. It hides, unless both parents pass it on.”

“I knew that,” Lindsay said, sniffing. “I was just testing to see whether or not you did.” She turned to Tanya. “I have hockey genes, too.”

“Hockey genes?”

Lindsay nodded. “From my dad and not my mom ’cause she comes from California and she hasn’t got any winter-sport genes in her at all. My dad’s teaching me to play hockey.”

“You don’t say. Well then, Lindsay Bolt-Tardiff, we have something in common, because when I was a little girl, believe it or not, I used to play on a girls’ hockey team at my school in Russia. We had a small league, but we were very good—at least, we thought so. I played goalie.”

“My dad plays center. I don’t play any position here because they don’t let girls on the teams. It’s not fair! I have to just skate around with my dad and we pass the puck. But I’ve got a killer slap shot,” she added. “I bet I could get it past you!”

“I am certain you could,” Tanya said, laughing. “I have not played in many years. Now, I just like to watch.”

“You could come and watch Daddy’s team play on Saturday. Mom? Couldn’t Tanya come with us?”

“Yes, of course. We’d love to have you join us. David’s team is just a bunch of guys from some of the foreign missions. Your embassy has a house team, too—David and his friends often play against them. But they’re playing a team from a local factory on Saturday morning. It’s not professional caliber or anything, but it’s fun. Why don’t you come and watch with us?”

“Oh, you are very kind, but I don’t think—”

“We could pick you up,” Lindsay offered helpfully, checking with her mother. Mariah nodded.

As she watched Tanya searching for a response, Mariah saw in her eyes that sudden fear—the fear born of dire warnings from KGB officers about what lies in wait for those who consort with capitalist enemies. And as Tanya’s eyes fell, Mariah saw regret, and then a flash of something else. Anger? Defiance?

“I would love to, really. But I do not think I can make it on Saturday. Thank you for asking.” Tanya looked at Mariah, hesitating, and then she turned and smiled at Lindsay. “I should be going now. I very much enjoyed meeting you, Lindsay,” she said, giving her a kiss on the cheek. “And you, Mrs. Tardiff.”

Mariah had unobtrusively scribbled something on a piece of paper. When Baranova held out her hand, Mariah pressed the slip in and left it there when she withdrew her own. “I wrote down the name of the arena,” she said quietly. “It’s near the Alte Donau U-Bahn station, in case you find yourself free on Saturday, after all. The game starts at nine. It was good to meet you, Tanya.”

The Russian woman held her gaze for a moment, and then turned and walked away.

In the end, Mariah recalled, Tanya had shown up that Saturday, somehow managing to shake the KGB watchers that kept tabs on all Soviet diplomats. And that was the beginning of it.

The hockey game was the only time, apart from the IAEA office party, that Mariah and Tatyana Baranova had ever met on open ground. But as the list of references on the computer indicated, they had met eight times again over the next fourteen months.

Then Tanya had disappeared and CHAUCER appeared to be wound up. Not long after that, David and Lindsay’s car was wiped out in front of the American School.

Mariah highlighted the first reference to CHAUCER on the screen, hoping against hope to find a back door into the file through her personal log. But when she hit the Enter key, the same stern message appeared: “RESTRICTED FILE. ACCESS DENIED.”

6

Rollie Burton stood in the shadow of a clump of blue spruce trees, invisible from the footpath, his mismatched blue-green eyes watching her through windows that ran the length of the swimming pool. His right hand nervously fingered the bumps and crevices of the carved ivory knife handle, anticipating the moment when he would put the blade to use.

A few minutes earlier, he had been sitting outside her house again, debating whether a break-and-enter job fell within the terms of his agreement with the voice on the phone and if so, how he would pull it off. Suddenly, she had surprised him by walking out her front door and heading off alone down the footpath. He couldn’t believe his luck.

He had slipped out of the car and started after her, being careful to keep to the shadows. He hadn’t had enough time to catch up and take her quietly before she arrived at the recreation center, but he was positioned now for a quick grab when she emerged. He hoped it would be soon. He was freezing.

He watched through the window as she stood at the edge of the pool, wrapping her toes over the tile lip. She crouched, arms pulled back, chin tucked, eyes riveted on the lane ahead of her. There was a brief pause when she seemed to hesitate. Then her arms snapped forward and her legs launched her through the air. The triangular point of her fingers poked an entry hole in the water through which the rest of her body neatly slipped, hardly rippling the surface. He watched as her legs kicked powerfully and her arms settled into the rhythm of the first lap. And as he did, Burton experienced a flicker of uncertainty. Most dames panicked when you jumped them, freezing like a deer caught in headlights. But she was strong—that much was obvious—and she might turn out to be a fighter.

He dismissed the worry with a snort. Hell, he’d taken down trained guerrilla fighters twice his own size. Ain’t no dame nowhere ol’ Rollie can’t handle, he thought. And he loved the look in their eyes when they first saw the knife.

As Mariah dived into the pool, the shock of the cold water cleared her mind of all but the most elemental instincts for a few blissful seconds. But then her thoughts eddied back, rushing to fill the void, as her body acclimatized to the temperature.

The Mariah Bolt who had stormed out of Frank Tucker’s office that morning was not the same woman who had walked in. For the past ten months, she had been running on automatic pilot, suppressing rage and pain in order to cope with David’s and Lindsay’s needs.

She had brought them home by military air ambulance, had seen David settled in—first in a neurological unit for further testing and diagnosis, then into a nursing home in McLean, Virginia, when his condition stabilized and the doctors had run out of hope.

She had also lined up doctors and physical therapists for Lindsay. That was the easy part of dealing with her daughter’s injuries—the hard part was helping Lindsay cope with the emotional trauma of the accident. Conscious and in horrible pain from her crushed leg, Lindsay had watched her beloved father nearly die in the forty agonizingly long minutes that it took rescue personnel to arrive and pry them out of the wreckage. While Lindsay seemed to have coped well with the tragedy, only Mariah knew the ache and fear she held inside, the tears too rarely shed.

And then there had been the practical matters of day-today living to get under control once they were back in the States—painful visits with lawyers and a judge to have David declared mentally incompetent and their joint assets signed over to her. There were financial arrangements to be made to ensure that he would have the care he needed for the rest of his life—a life whose term was uncertain, given the scarred remains of his brain and body and the likelihood of further complications.

Mariah had had to buy a car and a condominium alone, and move herself and Lindsay in, making sure that there was wheelchair access so that they could occasionally bring David home. She had arranged Lindsay’s school and music lessons and physical therapy schedule, and had then gone back to work at a new job at CIA headquarters at Langley. Ever since, the weeks had blended into one another, a blur of racing between home and hospitals, office and school.