Nothing but Ghosts

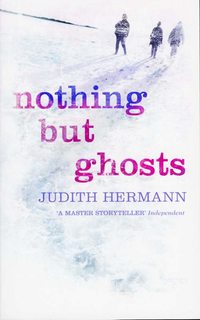

In the photo, the moon is suspended above the road that leads to the Old Althing. The sky is a glowing, diaphanous blue, everything else is white; the road is white, the mountains are white, blanketed in deep snow. Magnus, Irene and Jonina are walking towards the camera. Magnus in the middle; he is blurry, his face unrecognizable. Jonina is on his right, Irene on his left. The distance between Jonina and Magnus is greater than the distance between Irene and Magnus. Irene is laughing; she walks straight ahead. Jonina seems to want to walk out of picture towards the right but is looking directly into the camera. Jonas was standing in the middle of the road, his camera mounted on a tripod. Afraid that the light would change, he had yelled at them – ‘Now!’ Jonina remembers how he looked just then, his woollen hat pulled down over his eyes, the sheepskin jacket open, swearing at the cold, delighted and enthusiastic.

It’s not that Jonina has forgotten that beautiful, much-too-short, blue hour. She hasn’t forgotten it. She remembers it exactly, and if she wants to she can recall everything else too, each detail of those seven days. The Soviet star on Jonas’s belt buckle, the ring on Irene’s left hand – a moonstone in an oval setting – blueberry-flavoured Absolut vodka in a large frosty bottle. Coffee with sugar but no milk for Magnus in a snack bar on the Ring Road going north, the weather forecast on the third day they were together. Sunna’s childish drawing of two pugnacious snowmen and the colour of Jonas’s eyes – green, dark green with a thin yellow band encircling the iris. She hasn’t forgotten any of it. She just hasn’t been thinking about it any more. Thinking about it only induces a feeling of heaviness and weariness. And now she holds the photo in her hand early in the morning – nine o’clock, it’s not even light outside – and again she remembers everything. She can’t decide whether she wants to remember or not, but she can’t help it – everything comes back to her.

She recalls how she and Magnus were driving down the Barugata in their car; Irene and Jonas stayed behind, waving to them from the side of the road. ‘That’s that,’ Magnus had said, and Jonina wanted to say, ‘Stop, let me out. Let me out,’ but didn’t say anything. And they turned a corner and Irene and Jonas were gone, had vanished, once and for all. That was that.

She could hang the photo on the wall above the table, on the shiny grey unblemished wall and surprise Magnus with it when he got up. She could hammer a nail into the unmarred surface of the freshly painted wall and hang the photo on it. It is a beautiful photo. They’ll have to hang pictures in the apartment anyway. They’ll have to acquire things; there’s got to be some disorder and some dirt in this unlived-in cleanliness, otherwise she won’t be able to cope. But not this photo. Anything, but not this photo, not Jonas’s beautiful glimpse of this one, much-too-brief, blue hour.

Irene and Jonas were coming to Iceland for the very first time in late November. Magnus had known for a month they would be coming, but he doesn’t tell Jonina till fairly late: ‘I’m expecting visitors from Berlin tomorrow.’ Jonina doesn’t ask him why he waited so long to tell her. It will be disconcerting for him; visitors from the past are always disconcerting. On the other hand, she is rather curious. She has known Magnus for two and a half years. She had never seen him before that, and for Iceland that’s unusual, but that’s the way it was. They didn’t attend the same school; they were not distantly related; they hadn’t by coincidence gone to the same rock concert. They saw each other for the first time in 1999. Later they discover that Bjarni, the father of Jonina’s daughter, Sunna, had been Magnus’s best friend at school. They discover this long after all contact between Jonina and Bjarni was broken off. Magnus grew up on the west coast and Jonina on the east coast. When he was twenty, Magnus went to Berlin. Jonina went to ‘Vienna. Magnus studied psychology. Jonina studied literature. Twelve years later, they returned to Iceland at about the same time. In the end all Icelanders come back to Iceland, almost all. They study or work abroad and live there ten, twelve or fifteen years, and then it’s enough, and they come back. Almost all of them.

Jonina has never been to Berlin. She doesn’t know what that city in which Magnus lived for twelve years looks like. She can’t imagine what he looked like in those years, what he was like, what he did, can’t imagine him speaking German and spending his days with German girls.

When they first met, they talked a lot about those days abroad, how it felt to be a foreigner, and about the happiness and hardships experienced. They talked about it as if it were something that happened a long time ago and in no way affected the present. They never speak German with each other, not even for fun. They don’t even give it a try. A different Magnus and a different Jonina.

But she loves the story about Magnus’s first days in Berlin and the story about his departure. Perhaps she loves these two stories because they form a frame for the time before she knew Magnus; they enclose it and put an end to it.

Magnus was living in a one-room apartment in a rear building in Berlin-Neukölln. It is the winter of 1986 and colder in Berlin than it ever gets in Iceland, 20° below zero. His apartment has a tile stove but Magnus doesn’t know how to work it. All he has is a mattress, nothing else. When he comes home from the Institute, he lies down on the mattress with his clothes on, covers himself with a quilt, and smokes and reads. He has no curtains. His room faces the rear courtyard. Everyone else has curtains; he knows that they can see him lying in bed, smoking, alone – he doesn’t care. Around midnight he goes to a bar, annoying everyone there with his childish German, and stays till they throw him out. He knows some other Icelanders in Berlin, and he gets together with them, but he didn’t go there because of them. He’d love to meet someone, a foreign girl, just not a psychology student. But it doesn’t work; he remains alone. And then one day when he comes home, there’s a letter lying on the floor in the hall, dropped through the letterbox, a small, white, folded piece of paper. He takes the paper to bed, lights a cigarette, unfolds it and reads: ‘Hey, old man, I can see you, man. You’re pretty much alone and you lie around in your bed all evening and every weekend reading, and you really seem to be all alone, and I thought, maybe you could just drop in sometime. Side wing, fourth floor, left. Slick Chick.’ That’s all. Jonina loves this story. She loves it when Magnus mimics the Berlin accent: ‘Hey, old man, I can see you, man.’ And even though that was just what he had been wishing for, to meet someone by chance, he finds it impossible to simply drop in on someone who addresses him with ‘Hey, old man’. He never went to see Slick Chick; he doesn’t even know what she looked like. He says that sometimes he regrets it.

And then during his last days in Berlin, twelve years later – by then he had met lots of girls but didn’t yet know that these would be his last days there – he suddenly lost everything. He lost his apartment key, his money and his watch, he was fired from his job, hung out in bars with some guys he met, and had the feeling his whole life was coming apart, for no reason, inexplicably, out of the blue. He seemed to be falling and falling and there was nothing to check his fall. And then with the last of his money he bought himself the most beautiful suit he had ever owned, a pair of sunglasses, new shoes, and for two days and two nights he made the rounds of all the taverns and pubs in town. Early the third morning, at seven, he was standing at Hjalmar and Irene’s door in Schöneberg saying, ‘I’ve got to get some sleep. Would you please let me sleep here?’ And Hjalmar and Irene put him in their bed, closed the curtains and turned off the light. Magnus slept for two days, then he got up, said goodbye, broke into his own apartment, packed his things, left Berlin and returned to Reykjavíik.

‘Oh, Magnus,’ Jonina says and claps her hands when he tells her this story, ‘oh, Magnus, what a lovely story about your departure.’ Magnus hasn’t been back to Berlin since. He doesn’t keep in touch with the friends from those days any more. Jonina telephones a girlfriend in Vienna twice a year, that’s all. The past is shut as tightly as a clamshell. And then Magnus says, ‘Irene is coming to Iceland, and she’s bringing someone. I don’t know him; at any rate it isn’t Hjalmar and he’s not an Icelander.’

Irene. What a solid, compact, cold name. ‘Were you living with her?’ Jonina asks. It’s really the first thing she wants to know, and Magnus laughs a little defensive laugh. ‘No, never. She was with Hjalmar for a pretty long time; they didn’t break up till after I left Berlin.’

Irene is giving a slide lecture in Reykjavik about German architecture. Hjalmar gave her the phone number of another Icelander, in Japan, he in turn directed her to someone in California, and in California she was given Magnus’s phone number. She calls him and says, ‘Excuse me, Magnus. We haven’t been in touch for a long time. But I’m coming to Reykjavik soon and I thought we could get together.’

‘Are you looking forward to it?’ Jonina says. ‘In a way, yes,’ Magnus replies. ‘Of course I’m looking forward to it. It could turn out to be very nice. It could also misfire completely. I don’t know.’ You can’t know about anything, Jonina thinks. Dear Magnus, you can’t know about anything at all, and you always have to be prepared for the worst, and for the best too.

That year the snow came unusually early. In mid-November it is already four feet deep outside Reykjavík; the Ring Road has to be cleared daily; many of the roads leading into the interior of the island are closed; villages cut off from the outside world. In other countries the airports would be shut down in weather like this; not in Iceland. The planes of Iceland Air land even on iced-over runways. Irene and Jonas arrived at Keflavéik airport at the end of November, in a snowstorm with gale-force winds and below-freezing temperatures. Jonas will keep talking about it for the entire ten days of their stay.

Magnus doesn’t pick them up at the airport, although he has the time, but the first evening after their arrival in Reykjavik he goes to hear Irene’s slide talk. He really is interested in architecture. Jonina is driving to her parents’ summerhouse in Olurfsbudir with Sunna. ‘Ask them if they want to come to Olurfsbudir. Ask them if they’d like to drive out there,’ Jonina says. ‘Are you sure?’ Magnus asks. Jonina looks at him, annoyed. Of course she’s sure.

She’s been with Magnus for two years now. She-is thirty-five and has a six-year-old daughter who has no contact with her father any more. She met Magnus at a dinner at the house of some friends – he was described to her as someone she would surely be interested in, a psychologist, refined, a little odd, reserved and a bit mixed up, but good-looking; the description proved correct. Once they separated for four months, but now they’re together again.

She can’t stand it when Magnus asks if she’s sure. If she weren’t sure, she wouldn’t have said anything. She wouldn’t have invited Irene and Jonas – total strangers to her – if she weren’t sure that it would work out well. Or maybe not well. Why should it always work out well? They would either get along or they wouldn’t, whichever. She says, ‘I’d like to meet Irene, and it would be nice for Irene to get out of Reykjavék, so ask her,’ and then she drives off.

She has packed snowsuits, food, wine and packets of cigarettes into the boot of the car and has driven off with Sunna to Olurfsbudir. A cluster of small summerhouses on the west coast, six miles from the ocean – seventeen summerhouses on a hillside in the middle of the heath. Grassy hummocks, moss, dwarf shrubs, and on the horizon, very far away, the mountains. That is all. The summerhouses are simple low, log cabins, each with two small bedrooms, an eat-in kitchen, a terrace and a pool you can fill with hot-spring water.

Jonina’s favourite time to be in Olurfsbudir is winter when the snow has covered the heath and everything is white all the way to the blue mountains. It gets light at eleven o’clock and dark again at four. It is silent, vast and godforsaken – black herds of Iceland horses and the steam rising from the pool, the only things moving. And the light changes from minute to minute, fog, walls of fog, the sun, a sudden view of the mountains, the sky splitting open and drawing shut again with threatening, blue-black clouds, then again fog and no more light at all.

Jonina finds driving to Olurfsbudir soothing; it calms her nerves, her whole body and also her heart. She longs to sit on the sofa by the window in the wooden house, to stare out at the grassy hummocks and not think of anything. Even after all these years she still finds it purifying. She was afraid that Magnus wouldn’t know how to deal with Olurfsbudir when she took him out there for the first time, that he would think it all too monotonous, too quiet, but her fears were unfounded. Magnus enjoyed Olurfsbudir. On his first visit there, he took a small leather suitcase the contents of which Jonina inspected while he was in the bathroom. Three ironed shirts, three pairs of trousers, a perfect travelling case with shoe polish, brushes, polishing cloths, another case just as perfect containing sewing things, and a CD by Nick Cave. Jonina stood before the suitcase staring at its contents, at its touching and disquieting contents; then she snapped it shut again.

Magnus calls late that night. Sunna is already asleep. The other summerhouses are unoccupied in the wintertime. He says, ‘Well then, we’ll come tomorrow; they would very much like to come too.’ ‘What are they like?’ Jonina asks. ‘What’s the guy like and how did it go with Irene?’ Magnus laughs softly. Jonina feels a wave of affection; she suddenly feels very sorry for him; or rather, she would like to touch him now. It must really be awful – meeting again after such a long time. He says, ‘It was good. No, really, it was good. She gave a fine lecture and afterwards we went out to eat. It wasn’t difficult; actually it was the way it used to be,’ and Jonina says, ‘Then come. Don’t get here too late. It is very beautiful out here.’

Jonina folds the wrapping paper around the photo again; her breathing is shallow and quiet; her heart is pounding; she is afraid that Magnus might wake up any moment. He doesn’t. He is sleeping his sound, childlike sleep behind the white bedroom door. In the kitchen Sunna pours cornflakes into a bowl; the sound seems incredibly loud to Jonina. She gets up and walks over to the hall cupboard and puts the package under the boxes that contain her old school exercise books, her photographs and letters. She’s got to find another place for it, maybe get it out of the apartment entirely, or maybe she ought simply to show it to Magnus. She isn’t sure. ‘What are you doing,’ Sunna calls from the kitchen; it’s not a question, it’s a statement; she sounds suspicious and grown up. ‘Nothing,’ Jonina says. ‘I’m only putting things away.’ She has to laugh.

She, Magnus and Sunna moved into this apartment four weeks ago. When Irene and Jonas arrived in November, a year before, they had just bought it. They had been looking for a long time and then finally found it, a small five-room apartment in the old harbour district of Reykjavik, with trees outside the windows and plasterwork on the ceiling. They were both very busy at work – and so they planned to renovate in January and move in February. They began the renovation in March, painted the walls, enlarged one of the doorways, put in new windows, and everything was actually finished, but then Magnus pulled up a floorboard, then a second and a third and decided to lay new parquet floors.

At that point Jonina opted out. She simply let go. She let him do the renovating by himself, and he took the entire apartment apart and couldn’t finish, he simply couldn’t finish, and in dismay Jonina concluded that concealed behind his reserve, his quiet and absent-minded manner, there was an absolute mania for perfection.

For months after that she no longer went to the apartment. She just couldn’t stand it. She couldn’t bear to see the awful mess – the destruction of things that had really been quite all right, and Magnus still thinking of new ways to make more changes. Summer came, and finally autumn, and in October he forced her to come and look at the result. They stood facing each other in the empty living room where the sunlight fell on the shining parquet floor and the walls gleamed. The plasterwork on the ceiling was accentuated by white paint, the doorways leading from one room to the next were wide and high. The windows had received a third coat of paint, and a huge silvery refrigerator hummed in the kitchen. Sunna’s room. Your room. The dining room. Our room. Magnus took off his glasses; he looked ill. He said, ‘I still have to lay tiles in the bath,’ and Jonina said, ‘Either I move in tomorrow or not at all, ever. Take my word for it. Tomorrow or not at all,’ and then he gave in.

In the kitchen, Sunna, wise beyond her years, says as if she were talking to herself, ‘There’s nothing to put away here,’ and she’s right. Magnus didn’t have any things, and Jonina had sold her own furniture. In all the rooms except Sunna’s there was only what was absolutely essential. Perhaps Magnus thought this was the way it ought to be. This was how an apartment for the three of them should look. It had to be empty so that it could then be filled with their new, shared life. Maybe, in his awkward and insecure way, he had visualized it like that. But so far nothing has been added.

Jonina had sensed their friends’ astonishment, their embarrassed politeness: ‘What a wonderful apartment, such a lovely location. But it’s rather bare, isn’t it? You ought to hang some pictures, some photos, anything.’

‘Could it be that Magnus worked on the renovation for such a long time because he wasn’t actually sure?’ Jonina’s sister had asked hesitantly. And Jonina had said, ‘Could be. But I’m not sure either, and we still have time, all the time in the world.’ It was reassuring. Her sister’s conjecture reassured her. It was good to know that Magnus was afraid of living with her, of the decision and its outcome; she is afraid too.

She shuts the cupboard door, goes to join Sunna in the kitchen and sits down at the table with her. The tap is dripping. Sunna is silent. Jonina gets up to turn it off. Then she sits down again. Sunna eating her cornflakes from a lemon-yellow bowl, sleepily, slowly. The cornflakes crackle in her small, closed mouth. She gazes intently at her mother. It’s not yet light outside.

In Olurfsbudir, Jonina and Sunna spend the afternoon – the last hours before it gets totally dark again at five o’clock – on the terrace. Jonina is sitting in a garden chair in the snow; Sunna is in the pool. Jonina has set the water temperature at 40°C; whenever the water gets too cold, more hot water flows in automatically. The pool is made of turquoise-coloured plastic. The water glitters; the snow around the edge of the pool has melted, but deep drifts of it cover the terrace. Sunna is sitting in the blue water, naked; her cheeks are quite red, her eyes sparkle, an intense and disturbing turquoise. They don’t talk much; in general Sunna doesn’t talk much. The cold is a dry cold and there is no wind. The plain is white and smooth like a desert; the snow has covered the tough perennial grass. The Iceland horses are standing up to their bellies in snow, not moving. To keep Sunna from saying anything, Jonina doesn’t smoke; Sunna hates smoking.

Jonina can see Magnus’s car while it is still far off, maybe miles away, but in the clear air she can already see Magnus. He is driving slowly; his car doesn’t do well in snow, but he refuses to buy a Jeep. He says he isn’t the type for a Jeep, and he’s right. The car approaches at a tediously slow pace and stops at the foot of the hill on which the house stands. Jonina doesn’t move. Sunna doesn’t either, only the water ripples softly. Then the engine is switched off; it is quiet; the car doors remain closed. For one terrible moment, Jonina thinks it isn’t Magnus sitting in the car but someone else, someone she doesn’t know.

Then the car doors open, and Magnus gets out, Irene and Jonas get out. Jonina stands up. Magnus calls her name with exaggerated relief in his voice. She goes to meet them; they seem rooted to the spot, unable to move, just stand there, looking at the landscape, overwhelmed. Or they are only pretending to be overwhelmed? Jonina is always ready to assume the latter.

Had she known what Irene looked like, she wouldn’t have had to ask Magnus whether he had ever lived with her. She is too small. Too soft. Physically not enough of a presence for Magnus, who feels drawn to women who simply ignore his shyness, his tenseness and his absent-mindedness, and who win him over without his being aware of it. Maybe that’s how Jonina had done it. Or maybe she simply touched him, took him home with her and persuaded him to stay; she isn’t sure; she can’t remember exactly how it happened.

Irene looks shy and absent-minded like Magnus. She isn’t really short, but she isn’t tall either. Her face is tense, serious, intellectual, with girlish features. A young woman you would notice in the university library only because she’s already there when you arrive and is still there when you leave. Jonina knows and likes the type from her time in Vienna. The hand Irene now extends to her is cool, the handshake quite firm. She’s wearing an inappropriate denim coat lined with swan-white artificial fur. The artificial fur looks good on her, but the coat won’t keep her warm for more than ten minutes. Jonas is wearing a similar jacket of brown suede, also lined, a hippie jacket for a wintry Woodstock; naturally he’s wearing it unbuttoned. His jeans are tattered, his green woollen hat is pulled far down over his eyes. He has slung an army backpack over one shoulder; apparently he didn’t want to put it into the boot of the car. He doesn’t offer to shake hands with Jonina, but says, ‘Hey.’ Maybe that’s supposed to be Icelandic, but it sounds more American. ‘Hey,’ Jonina says in exactly the same tone of voice. He looks sexual. That’s the first word that occurs to Jonina for him; he looks sexual, and Irene looks pale. Magnus puts his left hand on the back of Jonina’s neck and gives her an awkward kiss on the lips. She’s told him often enough not to do that; he doesn’t have to openly demonstrate that they’re together. She can do without it; he seems not to believe her.

Jonas says, ‘Far out.’ He says it in German, abgefahren, pronouncing it’ab-ge-fahrn’ in a dark scratchy voice, and shakes his head. ‘Original, like on the moon.’

‘What’s far out? What do you mean by “far out”?’ Jonina asks in German. It feels odd to be speaking German, and Magnus’s German sounds weird to her ear.

Jonas shakes his head, looks at her for the first time; his eyes are green, dark green, a narrow yellow band around the irises. Maybe he’s trying to find an answer, but doesn’t say anything, merely stamps his feet on the snow a few times in his military boots. Irene’s expression is unfathomable; she lights a cigarette as if she thought she had to endure something for a long time yet.

Jonina takes a key out of her jacket pocket and hands it to Magnus. She says, first in Icelandic and then in German, ‘Show them their house.’ She points a short way up the slope where there’s an identical house for Irene and Jonas. ‘I’ve turned on the heat; you have to explain to them how the pool works.’ ‘Poool,’ Jonas says dreamily. Up on the terrace, Sunna emerges from the water and stands naked in the snow.

Outside the kitchen window the sky is now turning blue, the same deep blue that drove Jonas out of his mind every morning last year. Sunna pushes her bowl of cornflakes away, annoyed and tired, and says, ‘I’m leaving now.’ She has been attending school for four months and seems to be moving further and further away from Jonina. In the hall she laces up her boots, slips into her coat, and puts on her fur hat; she looks like an Eskimo, her eyes squeezed into slits. She comes into the kitchen again and kisses Jonina affectionately, then she slams the door shut behind her. The school is at the end of the street. Sometimes Jonina wishes it were further away so that she could take Sunna there, say goodbye to her at the school gate, and watch her until she disappears behind the big door. But Sunna doesn’t want to be taken to school. ‘Shall I take you?’ ‘No. I’ll go by myself.’