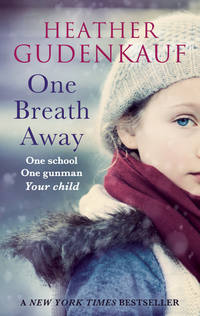

One Breath Away

Fully expecting my parents to finally say enough is enough and have Travis’s ass arrested for assault, they once again refused to press charges.

“What do you want to do?” Officer Demelo asked, and I looked up in surprise when I realized she was talking to me and only me.

“Now, now,” Officer Stepanich said, “this is really a parent decision.”

“I don’t think that wad of hair on the floor got there by itself and I can’t imagine that Meg here pulled it out of her own head,” Officer Demelo said, her eyes never leaving mine. I was surprised she remembered my name and even more impressed that she ignored the obviously senior officer’s lead. “Let’s see what she wants to do,” Officer Demelo insisted.

Travis smirked. He was six inches taller and about eighty pounds heavier than I was, but in that moment, knowing that only an ignorant coward would beat on his family the way he did, I felt stronger, more powerful. He thought he was invincible. But in that sliver of a moment, I knew that there was a way out for our family.

“I want to press charges,” I said, speaking only to Officer Demelo, who didn’t look much older than I was, but carried herself with a confidence I wanted for myself.

“You sure that’s what you want to do?” Officer Stepanich asked.

“Yes,” I said firmly. “I do.” Officer Stepanich turned to my parents, who looked bewildered but nodded their agreement. They took Travis away in handcuffs. He came back home a few days later. I expected him to exact some kind of revenge upon me, but he kept his distance, didn’t lay a hand on me. It didn’t keep him out of trouble, though. Over the years he’s been in and out of jail, most recently for drug possession. That arrest twenty years ago didn’t change Travis, but in my mind it saved my life.

“Travis will get nowhere near Maria,” Tim promised. He looked as if he’d like to say more, then settled on, “Talk to you later, Meg.” He drove away with Maria waving happily goodbye.

My windshield wipers can barely keep up with the thick snow that is falling. Great, I think. I’ll be shoveling for hours after I end my ten-hour shift at three o’clock. I debate whether to still make the Dutch letters tomorrow and decide to ditch that idea; instead, I’ll sleep in, watch TV, pick up a pizza from Casey’s and feel sorry for myself.

I feel my phone vibrate in my coat pocket. I peek at the display thinking it might be Maria. Stuart. Shit. I stuff my phone back into my coat. Stuart, a newspaper reporter who wrote for the Des Moines Observer and lived about an hour and a half from Broken Branch, and I called it quits about a month ago when I found out he wasn’t actually separated from his wife like he told me. Nope, they were still living under the same roof and, at least from her perspective, happily married. Yeah, the irony isn’t lost on me. I divorced my ex for screwing around and I end up being the other woman in some poor lady’s nightmare. Stuart said all the usual crap: I love you, it’s a loveless marriage, I’m leaving her, blah, blah, blah. Then there was the little issue where Stuart used me to get the biggest story of his career. I told him if he didn’t shut up I was going to shoot him with my Glock. I was only half joking.

I flip open the phone. “I’m working, Stuart,” I snap.

“Wait, wait,” he says. “This is a business call.”

“All the better reason for me to hang up,” I say shortly.

“I hear you’ve got an intruder at the school,” Stuart says in his breezy, confident way. Asshole.

“Where’d you hear that?” I ask cautiously, trying not to give away the fact that this is news to me.

“It’s all over, Meg. Our phone at the paper has been ringing off the hook. Kids are posting it on their walls and tweeting all about it. What’s going on?”

“I can’t comment on any ongoing investigation,” I say firmly, my mind spinning. An intruder at the school? No. If there was something going on I would know about it.

“Maria. Is she okay?”

“That’s none of your business,” I say softly. I wasn’t the only one Stuart hurt.

“Wait,” he says before I can hang up. “Maybe I can help you.”

“How’s that?” I say suspiciously.

“I can track the media end of things, keep you informed of what we hear, give you a heads-up on anything that sounds important.”

“Stuart,” I say, shaking my head. “Honestly, nothing you have to say to me is important anymore.”

Will

That morning, as Will Thwaite watched his grandchildren climb onto the school bus, the horizon not yet shaded with the petal-pink edging that comes before the sunrise, he realized, as he often did in the dark-cornered mornings, that he missed his wife terribly. He was so used to having Marlys there right by his side working the farm. She was the one who shook him awake at five each morning, the one who pushed a thermos of hot coffee into his hands and sent him out the door with the promise of a hot breakfast upon his return from feeding the cattle. He felt her absence the way one might miss a limb. Fifty years they would be married, this coming fall. He tried to remember the last time she had been away from the farm overnight and settled upon eleven years ago when she went to visit their fourth son, Jeffery, his wife and their newborn daughter in Omaha. She had packed a bag for four days, climbed into the Cadillac, hollered out the window that there were meals in the freezer for him to put in the microwave and drove away in a cloud of deep brown Iowa dust.

He sipped at his coffee, wincing at its bitter taste, not at all like Marlys’s, understanding why Marlys had to stay away for so much longer this time. It had been two months already and still she couldn’t give him a date when she would be returning home. Their youngest child and only daughter needed so much care and was having so many setbacks from the accident that it could be well into April before he would next see his wife. For many years Will thought that he might never see Holly again, she was set so hard against him. He suspected that if he tried to pin Holly down to exactly why she hated him, she wouldn’t quite be able to say, though she managed to poison his grandchildren against him. At least the boy, P.J., a quiet child with brown eyes, thick round glasses and the soul of an old man, had warmed to him rather quickly. The girl, Augustine—Augie—was a different matter altogether. When Will walked into the hospital, the cool institutional air a welcome reprieve from the dry, incessant Arizona heat, he felt a quickening of his pulse as he turned the corner and entered the burn unit. Slouching in an uncomfortable-looking chair was his daughter. But of course it wasn’t Holly, it couldn’t be. Holly was in a hospital bed recovering from third-degree burns. Besides, the forlorn creature before him was much too young to be Holly. But she had Holly’s pale skin, brown hair and plump roundness. Not fat by any means, but solid, in a healthy farm girl way, and he smiled inwardly at the thought. This was his granddaughter, and for a brief moment Will thought that this was his chance, his opportunity, to reclaim his wayward daughter, who for the past fifteen-odd years had dismissed him for reasons he couldn’t quite determine.

His hopes were quickly squelched when Marlys, always emotive and loud in the most inappropriate places, squealed in delight at seeing her grandchildren for the first time.

“Augustine? P.J.?” she asked loudly, causing the other visitors’ heads to snap up. She held her arms out to the children, expecting, Will supposed, for Augie and P.J. to leap from their seats and bound into them. Instead, the two gaped up at their grandmother, who Will had to admit was quite the sight. The worry over Holly, the frantic packing, the scrambling to make sure the farm duties were covered, had exhausted Marlys even before they left Broken Branch. Then there was their flight, the first ever for Marlys, and not knowing the ins and outs left her feeling small and inept. After finally arriving in Revelation and seeing her grandchildren, Marlys could no longer hold back the emotion. She gathered the stunned children into her arms, pushed them back from her at arm’s length after a moment to get a good look, then pulled them back to her.

“We’re your grandparents,” she cried through her tears. “Oh, aren’t you beautiful?” she said to Augie, whose mouth lifted into a wisp of a smile. “You look just like your mother did at your age. And you.” Marlys turned to P.J., lifting his chin with one work-worn finger. “Aren’t you a handsome young thing?” Her tears dripped down her wrinkled cheeks and plopped onto P.J.’s upturned face. The boy didn’t squirm away or wipe the moisture away from his forehead, but looked in awe up at his grandmother and then cast an unsure glance at his grandfather, who shrugged as if to say, I don’t know what she’s doing, either. When Will turned his gaze to Augie, hoping to share in the levity of moment, he was met with an accusing, suspicious glare. Holly had already filled his granddaughter with the tales of her childhood. The backbreaking work, the isolation of the farm, the battles over curfew, the unfairness of it all. While Marlys preened over the children, who basked in the attention, Will stepped back and busied himself with finding a nurse who could give him some information about the condition of his daughter.

Now, two months later, he was no closer to breaking down the wall that separated him from his granddaughter. God knows he had tried. He understood how hard being away from her mother must be for Augie and he tried to give her space. He waited one full week before telling her that chores were an essential part of living on the farm, that she needed to contribute. It had been easy with P.J., who followed his grandfather with rapt attention. Augie, on the other hand, would retreat to her room, Holly’s old bedroom, each day after school and wouldn’t emerge until the next morning. She answered any questions in monosyllabic grunts and refused to eat with them. Claimed to be a vegetarian, scowled and scoffed at the fact that he was a cattleman, that he raised animals for food. He knew better than to argue with Augie, tried to be patient. Though at times he thought he would explode with frustration, he vowed to try and educate her gradually, if not a bit gruffly. But she certainly didn’t make it easy for him. She still glared at him with disdain and took every opportunity she could to argue and disagree with what he said. It was like raising Holly all over again. But the thing was, over the years, after his relationship with his daughter had disintegrated into far-flung memories of when she was little and thought he hung the moon, he swore if he had the chance to do it over again, he would do things differently. Now the opportunity had presented itself in Augie, a clone of his daughter, and damned if he still couldn’t get it right.

Holly

Once again I woke up to another morning in the hospital. I’m beginning to think that I’ll never be able to leave this place. I want to rip the IV from my arm and run away screaming. My entire life I’ve been trying to get free, first from my folks and from Broken Branch and all its small-town hokeyness. Then it was from my marriage to David and the way being tied to one person, or maybe it was just him, suffocated me. So first I severed ties with my Iowa family, leaving them behind without a hug or a kiss, just an I’ve gotta get out of here or I’m going to die, and not once did I ever look back. Ran away to Colorado with a boy who I grew up with. We got sick of each other after only a year, so off I went to Arizona where I ended up going to cosmetology school. There I met David; we got married and had Augie. That fiasco lasted an entire seven years. He tried to get me to stay, said he wanted another baby, wanted to grow old together. I told him I couldn’t live this way anymore, that I would die if I had to wake up one more morning looking at the same god-awful flocked wallpaper or listen to our next-door neighbor go on and on about how the neighborhood was going to hell.

“We’ll take off the wallpaper,” David had said. “We can move,” he promised. So we took down the wallpaper and I got pregnant. But he knew. He understood that it wasn’t the wallpaper or the neighbors. It was us. Really me, who couldn’t stand being there, being married, being trapped in the suburbs, which isn’t all that different from small-town Iowa. David looked so hurt, so wounded, when he watched P.J. People tended to regard me that way after they’ve been around me for any length of time. First my mother and father. Especially my father. How I took private glee in the look on his face when I told him that living on a farm was like hell on earth, that spending one more minute in Broken Branch was a minute wasted, thrown away, never to be retrieved. My older brothers called me selfish and ungrateful. My mother cried. I felt bad about that. But it didn’t make me want to stay. My father actually helped carry my suitcase out to the old Plymouth Arrow I had saved up for by detasseling corn every summer since I was thirteen.

“You are seventeen years old, Holly,” my father said. “And I know you think you’ve got all the answers, but what you are doing to your mother is inexcusable.”

“I can’t spend another day here,” I told him, not able to look him in the eyes, instead staring over his shoulder out at the acres and acres of ankle-high seed corn. “I can’t explain it.”

My father was quiet for a minute. His green John Deere hat perched on his head, pulled low so that his eyes were shaded. But I already knew they were looking at me with disapproval. He leaned against the back hatch of the Plymouth, his tan arms folded across his chest. “You’re ashamed of being the daughter of a farmer? You think you’re too good enough for this life? Is that it?”

I shook my head, mortified. “No! That’s not it.”

“Well, from where I’m standing, it sure appears that way. I understand you wanting to travel, see the world, but there’s no need to leave this way, like you’ve waited your whole life to get away from your mother and me.”

But I have, I wanted to say to him, but didn’t. “I just can’t seem to stand myself in my own skin while I’m here,” I tried to explain, knowing that I was failing miserably.

“You think that’s going to change when you drive away from here? You think your skin is going to fit you any better?”

“Yes, in fact, I do,” I said, shaken that he had pegged it exactly. I was terrified that wherever it was I ended up I would feel the exact same way. That I needed to leave.

“You’ll be back,” my father said with a sureness that made my chest hum with anger. “You’ll come back, and when you do, you owe your mother an apology.”

“I won’t be back,” I spat back. “I’m never coming back here, ever.”

My father shook his head and laughed a little. A light chuckle. “Oh, you’ll be back.” He reached out to give me a hug but I stepped past him. “Well, I guess you’ve been through about every boy and man in the county, not much left to stay for.” I just climbed into my car without even saying goodbye. As I pulled away from the farm, I looked in my rearview mirror and there was my father, already turned away from me, surrounded by the dust and gravel kicked up into the air from my tires, heading toward his cattle that never seemed to disappoint and certainly never talked back to him.

I was true to my word. I had never returned, not once, to Broken Branch in the eighteen years since I left. But I wonder if I did the next worse thing by sending my children there.

Mrs. Oliver

Mrs. Oliver hardly dared to look away from the stranger standing in front of her, but the cries of her students pulled her gaze away from the man who looked vaguely familiar.

Sixteen of the seventeen children were helplessly staring up at Mrs. Oliver, some with tears in their eyes, waiting for direction as to what to do. The monthly tornado and fire drills had done nothing to prepare them for this. Not even the Code Red Lockdown drills could have readied them for the surprisingly calm, albeit slightly manic-looking man dangling a gun from his fingers. Only one child, P. J. Thwaite, the son of one of her former students, Holly Thwaite, was peering raptly at the man, scanning his face, not as if he knew him, but as if maybe, at one time, he had seen him somewhere before. The man stared back at P.J., his expression flat and unemotional, which unnerved Mrs. Oliver even more.

As a classroom teacher Mrs. Oliver couldn’t begin to count the number of times she had needed to appear unruffled and completely in control. There was the time, her first year teaching no less, when seven-year-old Bert Gorse, on a dare, decided to climb to the top of the tall steel slide and try to jump and grab onto the branch of a nearby maple tree. Mrs. Oliver remembered watching in horror from her position across the playground as Bert leaped into the air, his eyes screwed shut, his hands reaching for the branch, fingers clawing at the rough bark. “For God’s sake!” she yelled before she could stop herself. “Open your eyes!” Unable to grab the limb, Bert fell twelve feet to the hardscrabble earth below. Calmly, she told the little girl standing next to her to run as fast as she could to get help.

“You swore,” the girl breathed in disbelief.

Mrs. Oliver bent down and put her face so close to the little girl’s she could smell the peanut butter sandwich the child had eaten for lunch and said in the low, even tone that children for the next forty years would know to take seriously, “Run.” Trying not to wobble in her new high heels, Mrs. Oliver made her way as quickly as possible over to Bert, who was sprawled out on his belly, unmoving. The knot of terrified boys who surrounded Bert began unraveling at her approach. “Go stand next to the building,” she ordered, and the boys obeyed at once. Mrs. Oliver knelt down, the knees of her brand-new polyester pantsuit grinding into the dirt. Bert’s eyes were open but glazed over with pain or shock. “Not dead!” Mrs. Oliver said joyfully, and behind her the children erupted with a soft whoosh of relief. “Are you okay, Bert?” she questioned, but Bert’s mouth could only open and close soundlessly like a fish on dry land. “Got the wind knocked out of you?” she said in her smooth, low manner that the children found reassuring. Mrs. Oliver maneuvered herself onto her stomach and lay next to Bert so she could better see his pale, pinched face and where he could see her round, placid one. “It’s going to be just fine, Bert. Just lie still now until help comes,” she said soothingly.

Bert was okay, although he ended up with two broken arms and a collapsed lung. Once Bert regained the use of his hands, he wrote his teacher a lovely letter in his messy cursive, thanking her for waiting with him until the ambulance arrived. Mrs. Oliver still had that letter, now framed and hanging in the room that her grown daughter, Georgiana, called the Shrine to Mrs. Oliver. Bert Gorse was now a fifty-year-old banker who lived in Des Moines with his wife and three children. Through the years, Mrs. Oliver remained steadfast in her belief that a teacher needed to be calm and in control under any circumstance. Certainly unlike Gretchen Small, the young fifth-grade teacher, who began to hyperventilate when the fire alarm accidentally went off.

Mrs. Oliver straightened her spine, cleared her throat and willed her voice to emerge strong and clear. “What do you want?” she demanded, stepping between P.J. and the man with the gun.

Meg

I’m debating whether to give Stuart’s claim that there is a gunman in the school any credence and call dispatch when the squawk of my radio stops me short.

It’s Randall Diehl, our dispatcher. “You need to go over to the school right now. We’ve got a lockdown.”

Maria’s school. Damn. Stuart was right.

“What’s up?” I ask. Since I’ve lived here there have only been two lockdowns at the school, a kindergarten through twelfth-grade building. One of the last of its kind. At the end of this school year Broken Branch’s only school would be closed down; too expensive and outdated to maintain, the superintendent and school board voted to consolidate with three other nearby towns. In the future, Maria’s school district would be known as Dalsing-Conway-Bohr-Broken Branch Consolidated Schools.

The first lockdown I was involved with was two years ago when two inmates from the Anamosa State Penitentiary escaped and were thought to be in our area. They weren’t. The second time was when two misguided high schoolers called in a fake bomb threat. They hadn’t studied for their finals and thought this would cleverly get them out of the tests. It most certainly did that. And got them kicked out of school.

“We got a possible intruder in the school. Just head on over there,” Randall says impatiently, which was not like him at all. “The chief will meet you and he’ll fill you in. Communication is a mess. The 9-1-1 lines are jammed with calls from students, teachers, frantic parents.”

“Will do,” I tell him, and flip on my windshield wipers to clear away the snow. Interesting, Chief McKinney already at the scene. I check the clock. Just after noon. Probably just a misunderstanding, a prank by some kids to kick off spring vacation. Maria will be sad she missed all the excitement.

I turn the squad car around and head up Hickory Street toward the school and am grateful to have something to occupy my time besides the thought of spending four whole days without Maria, which makes me feel empty, as if my insides have been hollowed out. Tim always said he couldn’t ever imagine me as a kid. The few pictures that I had of myself as a child showed me as a serious, unsmiling creature with unkempt hair, wearing a pair of my brother Travis’s old jeans.

“Did you ever have any fun?” Tim teased when he first saw the photos.

“I had fun,” I protested, though that was pretty much a lie. My childhood consisted of taking care of my parents, who, for reasons still unknown, were completely defeated by life, and trying to stay out of the way of my volatile brother. When Tim and I had Maria I was determined to make her childhood as carefree and joy-filled as mine wasn’t. I think we did a pretty good job of this, at least until the divorce, and even then Tim and I did our best to protect Maria. We didn’t argue in front of her, we didn’t bad-mouth each other, but she knew. How could she not? Even if we didn’t make a big spectacle out of the end of our marriage, she had to have seen my red, swollen eyes, Tim’s tight, forced laughter.

In minutes I pull up to the school and find Chief McKinney already there along with Aaron Gritz—curious, because he isn’t on duty today—trying to keep a small, angry-looking group away from the school’s entrance. Chief McKinney’s deep baritone fills the air. “Go on back to your cars or you are all going to freeze standing out here. We need to find out exactly what’s going on and we can’t do that if we have to concern ourselves with—”

A woman steps forward, waving her cell phone, and in a trembling voice interrupts the chief. “My son just called me from inside and he said there was a man with a gun. Can’t you get them out of there?”

“Based on the information we have,” Chief McKinney says patiently, “we’ve determined that the best response is to contain the area and not send officers into the school at this time.”

“But my seventh grader called and said there were two men,” another woman speaks up.

A man in a dress shirt and tie, no coat, rushes forward. “I heard there’s a bomb threat. Are you evacuating?”

“This is exactly what the problem is,” Chief McKinney says to me in a low voice, pointing first at the school and then the crowd, snowflakes collecting on his bristly gray mustache. “We can’t begin to know what’s going on in there if we’re chasing rumors out here.” He turns his back to the crowd and drops his voice to a whisper. “Meg, dispatch got a call from a man who says he’s inside the building with a gun. Said for everyone to stay out or he’ll start shooting. I want tape and barriers set up around the entire perimeter of the school.” He turns to Gritz. “Aaron, escort everyone about three hundred feet back.