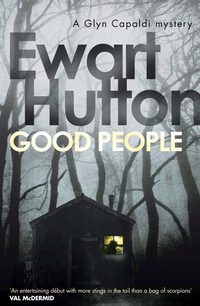

Good People

‘I can’t authorize a helicopter search.’

‘Yes, you can.’

‘I need senior officer clearance.’

‘Call DCS Galbraith.’

‘It’s a Sunday,’ a note of panic rising in his voice at that prospect.

‘And this is an emergency. I have seven people missing up here in conditions of extreme exposure. One of them is a young woman. You take the fall if any of them die or suffer serious injury.’ I let that doom note resonate for a moment before pressing down on the exaggeration pedal. ‘You don’t know what it’s like. I’m talking mountain conditions here, an enormous wind-chill factor, snow, a warren of forestry trails to be covered.’ The last bit, at least, was true.

‘Is a helicopter any use if it’s snowing?’ he asked.

‘It’s passing over,’ I said quickly, ‘but the wind’s getting colder.’

‘Okay,’ he came to a decision, ‘I’ll set it up, but it’s your responsibility. I am only acting on information received.’

It’s only accounting, I told myself, the budget must have an allocation for such emergencies. I raised a thumb of acknowledgement to Emrys, who was down at his own car, on the radio to his boss, trying to get more people in for the search.

But where to start? I traced the course of the minor road with my eyes until it disappeared into the forest that rolled outwards and onwards for hectare after hectare. New growth, old growth, clearances, logging trails, abandoned trails, and the bastard, shape-shifting magic trails that I always ended up getting lost on. The imminent prospect of moving into that forest held no appeal.

The imminent prospect of a call from Detective Chief Superintendent Galbraith was even less appealing.

I had a lot to blame Jack Galbraith for.

For a start, he had rescued me. After my career in Cardiff had effectively gone down the tubes, he had stepped in and offered to have me in the Carmarthen Division. The Wild and Woolly West, as we used to say in Cardiff. I had thought about it when I had gone in to clean out my desk in that strangely empty squad room. After they had told me that it was safe to surface from my “emotional” leave. Why was he taking in a burned-out and redundant “hero”? Jack Galbraith did not have a reputation as a philanthropist. Had someone in high places called in a big favour? Or was he setting up an even bigger one, to be redeemed at some future date?

‘I’ve been informed that you used to be a good cop, Capaldi,’ he had told me on that first day of my official reincarnation in Carmarthen. When I had been born again as one of his men. ‘That’s why you’re here with me instead of wearing a rinky-dink security uniform and patrolling the booze aisle in some shanty-town supermarket. I’m giving you another chance. See if you can get back some of that good judgement that you occasionally used to demonstrate.’

‘Thank you, sir,’ I had replied humbly.

‘Look at this.’ He walked across his office to the map of Wales that hung on the wall.

I looked. He tapped the map, a drummer’s rhythm. I didn’t have a clue what I was supposed to be looking at. He was tapping the bit in the middle, the empty bit, the bit God gave to the sheep.

‘Do you know how much it’s costing … to send men out from here …’ he rapped the pen on each of the divisional headquarters, then came back into the middle again ‘. . . to here? Every time a case comes up?’

‘I can imagine.’ I nodded sympathetically.

‘Overtime, petrol, hotel bills if they have to stay over.’

‘And you’re paying out for unproductive time with all that driving,’ I added helpfully. I would have kept my mouth shut if I had known what was coming.

‘Exactly. You’ve hit it right on the head there, son. Unproductive bloody time.’ He sat down on the edge of the desk. A power move. Looking down at me, nodding at the question before he had even framed it. ‘So what are we going to do about it?’

I didn’t even pretend to think that I was being invited to advise on strategy here. ‘I don’t know the answer to that, sir.’

‘I’m going to try an experiment, Capaldi.’

I gave him my best fresh, interested look.

‘I’m going to put a man in there. A resident detective, someone who can cover the routine crap, so back-up only gets called in when it’s absolutely necessary.’

Something plummeted. I felt like a specimen butterfly watching the mounting pin descend. ‘You’re surely not thinking of me for this, sir, are you?’

He grinned. It wasn’t meant to be friendly. ‘I’d have thought you would be grateful for any chance.’

‘I’m straight out of the city, sir.’

‘And you fucked up good there, didn’t you?’ He didn’t embellish. Didn’t remind me that I was responsible for the messy death of a man. He didn’t have to; the memory still kept me on familiar terms with the Hour of the Wolf most nights.

‘But I wouldn’t know how to operate out there,’ I protested, not faking my bewilderment.

‘Don’t fret your head about that, Capaldi, No one fucking does.’

We cordoned off the minibus with incident tape, and set up the command post there. With all that country to cover it was as good a place as any.

We had a mountain-rescue team on its way down from Snowdonia, volunteers from Forestry Services, and police teams with dogs already working their way into the forest. Inspector Morgan, Emrys’s boss, had turned up and was now running the uniform end of things. Apart from some filthy stares, he kept away from me, and left me in charge of the communications with the helicopter. Which was ominous. Had me wondering whether perhaps there wasn’t an emergency budgetary allocation after all.

My mobile rang. A number I knew only too well.

‘Capaldi …’ the voice boomed.

My stomach clenched. ‘Yes, sir.’

‘We’re on our way.’

The wind had dropped, the rain had thinned to a fine suspension. It wasn’t quite the Ice Queen blizzard that I had invoked. ‘I don’t think there’s any need, sir. There’s nothing to do but wait, you’ll just get cold and wet up here.’

Jack Galbraith chuckled darkly. ‘Don’t think you can call up a fucking circus, Capaldi, and not invite the chief paymasters. I’m bringing DCI Jones up with me. If my Sunday’s fucked I may as well spread the misery.’

‘Yes, sir,’ I replied snappily. Bryn Jones was one of the few cops in Carmarthen who hadn’t treated me like an AIDS carrier when I had limped in damaged from Cardiff.

‘Give me the background,’ Galbraith instructed.

I laid it out for him. Emrys Hughes couldn’t expect low profile now, so I nudged up the spin of the hijacking to six booze-fuelled guys and an unknown but vulnerable woman. Seven people missing in the hills. I played down the discovery of the neatly presented minibus. That didn’t fit in so well with the dark-tale storyboard.

He was silent for a moment, and then I could just make out indistinct conversation at the other end of the line.

‘You’re wrong.’ He came back on the line.

‘Sir?’

‘We think you’re wrong. This group isn’t the sort to be involved in anything truly sinister. You’ve been watching too much redneck massacre shit.’

‘It’s the woman that I’m concerned about, sir.’

‘The men don’t fit the gang-rape mould.’

‘What do you think I should have done, sir?’

‘Waited.’

‘I’m sorry, sir, you’re breaking-up …’ I cut the connection.

That was an unofficial rebuke. Was it going to end up turning official? Had I overreacted? I thought hard about it. No. Even Emrys Hughes had been spooked when he realized that none of those good people of his had made it home. But where had they made it to?

The helicopter’s call sign squawked over the radio. ‘DS Capaldi – we think we might have a sighting for you.’

‘Think?’

‘You’re looking for seven people?’

‘Check.’

‘We’ve only got five here.’

‘What about stragglers?’

‘I’ve circled. There’s only five.’

‘Is one of them a woman?’

‘Sexometers aren’t standard operating equipment.’ I could hear the laugh in his voice. ‘And from this high up I can’t distinguish tits.’

Two of the party apparently missing, and this funster thinks it’s a joke. I was tempted to tell him to check his mirror if he wanted to be able to distinguish a real tit.

2

I got to the location first. I needed to stay ahead before Morgan could pull rank and swamp me. I had to cheat to make sure of it. Knowing my luck with the weirdness of forestry tracks, I got the helicopter pilot to call the turns and guide me in.

I stopped the car as soon as I saw them.

Five men. Even from this distance I couldn’t mistake them. I felt the bad tickle in my kidneys again. Somewhere in the night we had lost the woman. One of the men, too, by the look of it.

I let them come to me. I wanted time to observe them. They were making their way down an incline on a forest track between new-growth fir trees. All were dishevelled. Some of the faces seemed vaguely familiar. The two at the front, similar in height, had the look of brothers. The older-looking of the two had his mouth set in stock chagrin, the other one was experimenting with damping down his smirk, trying to tamp some regret in.

They both met my stare. I had the impression that they had been practising.

The three following behind were having a harder time of it. The one in the middle, an enormous guy, had his shaved head drooped, and his arms draped around the shoulders of his two companions, who were bracing themselves to keep in step with his lurching pace.

The big shaven-headed guy was wasted. The other two were using the effort of supporting him as an excuse to look anywhere but my way.

I heard vehicles pulling up behind me, car doors opening. I didn’t turn round. My car was blocking the track so no one could get past. I concentrated, trying to read an explanation. The only consolation so far was that there was no spilled blood in evidence.

‘Where have you been, Ken?’

I was suddenly aware of Emrys Hughes standing beside me.

Ken – Mr Chagrin, the older of the two who looked like brothers – shook his head and pulled his mouth into a tight grimace of shamed apology. ‘We’re really sorry to have put everyone through this, Emrys.’

‘What happened to you?’ Hughes asked entreatingly.

‘We spent the night in Gordon’s shooting hut. Up by the old dam.’ He pulled a wry, regretful smile. ‘We were abandoned.’

‘Where are the rest of you?’ I pitched in.

‘Sergeant –’ Emrys and I both turned instinctively. Inspector Morgan glowered at us. ‘This is not an open inquisition. I want these men to have medical attention as a priority. And then they’ll be taken down to Dinas and given hot food and dry clothes before we even think about asking questions.’

‘We need to know about the others, sir,’ I protested. ‘There could still be lost or injured people up here.’

‘It’s just us, Inspector. There’s no one else, and no one’s hurt,’ Ken said penitently, then gestured back towards the big slumped guy, ‘Paul just over-indulged a bit.’

‘What about the woman who was with you?’ I demanded.

He smiled apologetically. ‘I expect she’s back in Cardiff by now.’

‘Where’s Boon?’ Emrys asked, before I could ask Ken for clarification.

‘Sergeant Hughes, Sergeant Capaldi, that will do!’ Morgan shouted angrily.

We stood back to let the five men shuffle past us like a file of train-wreck victims, paramedics coming up to meet them. The conscious ones gave Emrys Hughes a shamefaced smile as they passed. No one looked at me.

‘When do I get to talk to them, sir?’ I asked Morgan.

‘You don’t, Sergeant Capaldi.’

‘Sir?’

‘DCS Galbraith’ – I could tell that it hurt him to say the name without spitting – ‘is diverting directly to Dinas. He will interview them himself. And he didn’t request your presence,’ he added, clawing back a little consolation from my expression.

I couldn’t get over it. Suddenly no one was worried any more. By my reckoning we still had two missing persons to account for. But, since these five had turned up without any severed heads in string bags, the consensus appeared to be that everything was sorted.

I tackled Emrys about it before he joined the convoy driving back down the hill.

‘Don’t fret, Capaldi. It’s over.’

‘You don’t know what’s happened.’

‘Not the detail. But I trust these people. If there were any kind of a problem they would tell me. I know that they wouldn’t go calmly into those ambulances if there was anyone still in trouble up here.’

I couldn’t share in his faith. I kept it to myself, but another thing rankled. Even scrubbed up and alert, I couldn’t picture any of these guys in Calvin Klein underpants, or wearing Paco Rabanne aftershave.

So it looked as though I was the only one who had not been sprinkled with happy dust. Was the Italian side of me not seeing something that the Welsh side could embrace? Okay, I could run with it. I didn’t know these men, I had been excluded from the enchanted circle, so I was allowed to be mean-spirited.

I could dig for dirt.

But first I had to find it. The groups that had made up the search party were dispersing. I homed in on a Land Rover with Forestry Commission on the side and two bushy-haired occupants rolling cigarettes. They looked out at me as if I was a swish who had just dropped in from a piano bar through a hole in the space-time continuum.

I buttonholed the driver. ‘They said that they stayed at a shooting hut up there. Near an old dam.’

‘Right.’ He nodded, staring at me, waiting for something strange to happen.

‘Do you know where it is?’

They shared a silent geographer communion. Then the passenger leaned forward, his finger starting to point, his visible thought process chewing through the directions he was about to give me.

‘Great, I’ll follow you,’ I exclaimed, slapping the side of the Land Rover with macho gusto, like I was a roustabout jefe getting the crew rolling. I ran to my car hoping that they would assume we had just made some kind of a deal.

It worked. They blazed a convoluted trail, which may have been intended to shake me off. But I hung on behind them until the passenger flashed me a hand sign to let me know that we had arrived. I realized very quickly that it also indicated they were not stopping.

The hut was a long, low, timber-boarded affair, like a barrack, with a sagging mineral-felt roof, and plywood squares replacing some of the missing window panes. Well on its way to dereliction. It looked like the kind of place construction workers would have used. The only reason it had lasted this long was because no vandal could be bothered to take the kind of exercise required to reach it. The area in front had been cleared and levelled, but it was rutted and potholed now, and self-seeded birch and spruce saplings were collaborating with gorse in an effort to take over.

They had called it a shooting hut. On the drive up here, I had imagined something with rustic pine supports and trophy antlers nailed to the walls. This was more like a stalag way past its sell-by date.

I stood outside trying to get a feel for the place. Imagining it was night. Why would they come here?

Because it was so far off the edge of the world that anything could happen, and no one would ever be any the wiser?

I buried the thought. I went back to the facts. The minibus driver had said that the men didn’t seem to know the girl. So she wasn’t local. This location had to be the choice of one or all of the six men. It’s night, it’s cold, it’s late, and it’s a long way into a labyrinth. Why here? And why walk? Why not use the minibus? Why park it way the hell over where we found it? Because you were all so fucked-up that it seemed like fun at the time?

Because your party was still flowing?

I opened the door and met the party. Beer bottles and cans mainly, some wine, one bottle of vodka. All empty. But all stacked neatly. Tidied up. With empty crisp and snack packets crumpled and stuffed into a supermarket carrier bag.

The place had the damp, earthy smell of fern roots. I was standing in a vestibule. To my left was a small room that would have functioned as an office or foreman’s room, to the right a larger room, door hanging open: the mess quarters. In front of me, opposite the entrance, was a toilet cubicle with no door, and a cracked WC pan.

I went through the open door into the mess room. The floor had been swept. Not thoroughly; scrappy piles of old pine needles, twigs and other debris that had blown in through the broken windows had been pushed back against the wall. The other homely touch was six – I counted them – sawn log rounds arranged as seating. It all implied organization.

But when? Had this been set up before they arrived? Premeditated? Or had they all piled out of the minibus and set to making an impromptu den? And why only six pixie stools for seven people?

None of the log rounds had been recently cut. I touched the nearest one. It was still damp. But in this atmosphere so was everything else. I looked out of the windows. There were no other log rounds in sight. No imprints of any in the soft ground around the hut. It was possible that they could have ranged out with torches and collected these in the dark. Or they could have had them here already. But only six? Almost but not quite knowing how many were coming to dinner.

I nearly missed it. Running a last check before I backed out of the room I caught a glimpse of white behind the door. White and clean – alien matter in this place. I picked it up carefully. It was a crumpled paper tissue, slightly damp from absorption of the moisture in the atmosphere. I took a deep sniff. A complex background of unidentifiable fragrances. Opening it out I saw black smudges. The lessons from a fractured marriage informed me that these were smears of ruined mascara. Tears of fun or tears of terror? Another thought to bury.

I had made contact. My first meeting with the woman. I sniffed the tissue again to fix the esters in my olfactory library, and then fitted it carefully into an evidence bag.

I went back to the vestibule. The door to the small office was stuck. A clean section of arc in front of it showed where someone had tried to push it open and given up. Or had they? I put my shoulder to it and leaned in hard. It screeched horribly against the floor and opened with difficulty. The space was dark and even mustier than the mess room. Some damp Hessian sacks had been nailed over the windows. I pulled one away, grimacing at the slimy feel of it in my hand.

There was so much crud piled on the floor that I looked up reflexively, wondering whether this section had lost its roof. It hadn’t. But, even if it had, dead bracken did not usually tumble out of the sky in quantities like this. This had been imported. It had been heaped against the far wall, and it looked as though it had been compacted. To make some kind of a nest?

Another thought struck me.

To make a rudimentary bed?

DCI Bryn Jones was smoking outside the Methodist Church Hall in Dinas when I drove up. In the absence of a police station the hall had been commandeered for the occasion.

I ran up to him. ‘I’m sorry I took so long, sir. I got lost trying to find my way out of the forest.’ It wasn’t a lie. It was late afternoon now, almost dusk.

He just nodded, slowly exhaling smoke through his nostrils, a slightly ambivalent smile forming. ‘Thanks for your contribution to my Sunday, Sergeant Capaldi.’

Bryn Jones was short, but big in breadth. With tight black curly hair, happy green eyes, and a massive face that looked like it had been formed by pounding putty into place. He had a neck that seemed reluctant to narrow, and in the dark blue suit he appeared more constrained than dressed.

I gestured inside with my head. ‘Is DCS Galbraith in there working on them?’

‘Notice an absence?’

I looked around, puzzled. Not getting it at first. And then it hit. There was no one here.

‘Wives and girlfriends, concerned family …’ Bryn confirmed, seeing it dawn on me.

‘Where are they?’

‘Gone.’

‘Have you taken them in?’ I asked, surprised, wondering whether to start feeling vindicated. ‘Is it turning out to be more serious than we thought?’

‘They’ve gone home. All of them.’

I stared at him for a moment, perplexed. ‘Even the men?’

He nodded. ‘Even the men.’

I shook my head, trying to clear a path to my next question. Then the inner voice of self-preservation sideswiped me. ‘DCS Galbraith – has he gone home too?’ I asked, trying to conceal the hope in the question.

Bryn dropped his cigarette end, crushed it underfoot, and then shook his head. Not unkindly. ‘No. I’m on lookout duty.’

I didn’t have to ask who the smoke on the horizon was.

Jack Galbraith was sitting at a stacking table at the end of the hall, an empty plastic chair beside him, and an identical one opposite. He was having a cigarette under a sign that read Please refrain from smoking under the eyes of the Lord.

He looked up when I entered, closed his eyes, and steepled his fingers. I hoped that he was looking for guidance. Trying to find the strength to stop him swearing under the eyes of the Lord.

‘Fuck you, Capaldi.’ His eyes flicked open. ‘Where do I fucking start?’

Bryn Jones slipped into the empty chair beside him.

Even seated, you could tell that Jack Galbraith was tall. He had light brown hair swept back in a swagger behind his ears, a strangely effeminate frame for the firm, square-boned face with its deep-set, incisive, brown eyes. He looked as though he had been built for stamina, for distance and endurance, and you could tell from his bearing that he thought that he still had it, just hadn’t tried it out in a long time.

‘My wife thinks this is a put-up job to stop me taking her to an amateur choral rendition of fucking Elijah …’ All his years in Wales had hardly touched the gruff Scottish accent. He ticked the points off on his fingers: ‘That supreme fucking tosser Inspector Unctuous Morgan has witnessed my ritual humiliation. And you called out a fucking helicopter.’

‘No disrespect, sir, but we are in a church here,’ Bryn said quietly, out of the corner of his mouth.

‘No we’re not,’ Jack Galbraith corrected him. ‘We’re in a church fucking hall – there’s a difference. In here, I’m allowed a few transgressions.’ He paused to dump his cigarette into the residue of a mug of tea before fixing his gaze back on me. ‘What have you got to say for yourself, Capaldi?’

‘I thought we had a situation, sir. I had seven people missing, one of them a woman, in extreme weather conditions. I made a decision that seemed to be appropriate for the circumstances as I saw them at the time.

‘I was especially worried about the woman – a hitchhiker, picked up by the men. She didn’t know them. And the men were drunk. In my opinion she was vulnerable. And I’m still concerned for her. Do you remember the Broussard case, sir? In Cardiff? About six years ago? A Haitian illegal immigrant?’

‘There’s no parallel.’ Jack Galbraith shook his head and smirked. ‘Tell him, Bryn,’ he instructed. ‘Give him the low-down on the little flower he’s so concerned about.’

‘She was a hooker, Sergeant.’

‘A Cardiff tart,’ Jack Galbraith amplified. ‘Called herself Miss Danielle.’

I tried to absorb my surprise. ‘They picked her up in a rural petrol station. The minibus driver said she was hitching.’

‘That was the cover story,’ Bryn explained.

‘It was organized, Capaldi.’

‘It was meant to be a stag event,’ Bryn clarified. ‘They were setting up a surprise for the two bachelors in the group. They were meant to believe that the girl was just an innocent hitchhiker.’

‘Then, surprise, surprise, the girl drops the Young Rambler guise’ – Jack Galbraith clapped his hands together – ‘and at least one of our two virgins gets his rocks off, courtesy of his buddies.’