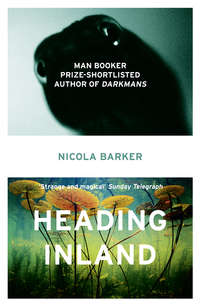

Heading Inland

Jack held his hands aloft, limply, gave her a watery smile but made no attempt to righten them. Carrie, in turn, put her hand to her curls. She imagined that Jack must be enormously clever to be so vague. Maybe a scientist or a schoolteacher at a boys’ private school or maybe a philosophy graduate. Not for a moment did it dawn on her that he might be a fool. And that was sensible, because he was no fool.

Carrie met Sydney two decades later, while attending self-defence classes. Sydney had long, auburn ringlets and freckles and glasses. She was Australian. Her father owned a vineyard just outside Brisbane. Sydney was a sub-editor on a bridal magazine. She was strong and bare and shockingly independent. On the back of her elbows, Carrie noticed, the skin was especially thick and in the winter she had to apply Vaseline to this area because otherwise her skin chapped and cracked and became inflamed. The reason, Sydney informed Carrie, that her elbows got so chapped, was that she was very prone to resting her weight on them when she sat at her desk, and also, late at night, when she lay in bed reading or thinking, sometimes for hours.

Sydney was thirty years old and an insomniac. Had been since puberty. As a teenager she’d kept busy during the long night hours memorizing the type-of-grape in the type-of-wine, from-which-vineyard and of-what-vintage. Also she collected wine labels which she stuck into a special jotter.

Nowadays, however, she’d spend her wakeful night-times thinking about broader subjects: men she met, men she fancied, men she’d dated, men she’d two-timed, and if none of these subjects seemed pertinent or topical – during the dry season, as she called it – well, then she’d think about her friends and their lives and how her life connected with theirs and what they both wanted and what they were doing wrong and how and why.

Carrie appreciated Sydney’s attentiveness. If Jack had been working late, if Jack kept mentioning the name of an actress, if Jack told her that her skin looked sallow or her roots were showing, well, then she would tell Sydney about it and Sydney would spend the early hours of every morning, resting on her elbows and mulling it all over.

Sydney had a suspicion that Jack was up to something anti-matrimonial and had hinted as much to Carrie. Hinted, but nothing more. Carrie, however, took only what she wanted from Sydney’s observations and left the rest. In conversational terms, she was a fussy eater.

Jack walked out on Carrie after twenty-one years of marriage, two days before her forty-fourth birthday. The following night, after he’d packed up and gone, she and Sydney skipped their karate class and sat in the leisure centre’s bar instead. Sydney ordered two bottles of Bordeaux. She wasn’t in the least bit perturbed by Carrie’s predicament. In fact, she was almost pleased because she’d anticipated that this would happen a while ago and was secretly gratified by the wholesale accuracy of her prediction.

‘You’re still a babe, Carrie,’ Sydney whispered, pouring her some more wine. ‘You could have any man.’

‘I don’t want any man,’ Carrie whimpered. ‘I only want Jack. Only Jack. Only him.’

‘That guy Alan,’ Sydney noted, ‘who takes the Judo class. I know he likes you. Sometimes it seems like his eyes are stuck to your tits with adhesive.’

‘Please!’

‘It’s true.’

‘Jack only walked out yesterday, Sydney, probably for a girl fifteen years my junior. You really think I care about anything else at the moment?’

Sydney had great legs; long and lithe and small-kneed. Gazelle legs, llama legs. She crossed them.

‘I’m simply observing that Jack isn’t the only shark in the ocean.’

Carrie took a tissue from her sports bag and dusted her cheeks with it.

‘I remember the very first time I ever met Jack, waiting for a bus outside the National Portrait Gallery. A Sunday afternoon. He had his coat buttoned up all wrong and I pointed it out to him and we started talking . . .’ Carrie stopped speaking and hiccuped.

Sydney chewed her bottom lip. That old three button trick, she was thinking. The slimy bastard.

‘You know, Carrie,’ she said sweetly. ‘You’re still so beautiful. You’re still the biggest lily in the pond. You’re still floating on the surface and bright enough to catch the attention of any insect or amphibian that might just happen to be passing.’ She paused. ‘Even a heron,’ she added, as an afterthought.

Carrie scrabbled in her sports bag. She grabbed her purse, opened it, took out a twenty-pound note to pay the barman for the bottles of wine.

‘My treat,’ Sydney interjected.

Carrie paid him anyway. She was about to shut her purse but then paused and delved inside it.

‘Look,’ she said, her voice trembling, holding aloft a blue card.

Sydney put out her hand. ‘What is it?’

‘Our season ticket to the ballet. We went every week. It was one of those routines . . .’

‘Well,’ Sydney took the ticket and perused it, ‘you shall go to the ball, Cinders.’

‘What?’

‘You and me. We’ll go together. When is it?’

‘Wednesday.’

Sydney handed the card back. ‘Fine.’

As it turned out, Sydney couldn’t make it. She rang Carrie at the last minute. Carrie answered the phone wrapped up in a towel, pink from a hot bath.

‘What? You can’t make it?’

‘But I want you to go, anyway. Find someone else.’

‘There is no one else. It doesn’t matter, though. I wasn’t really in the mood myself.’

‘Carrie, you’ve got to go. Alone if needs be. It’s the principle of the thing.’

‘I know, but it’s just . . .’

‘What?’

‘It’s kind of like a regular box and we share it with some other people and if I go alone . . .’

‘So? That’s great. It means you won’t feel entirely isolated, which is ideal.’

‘And then there’s this fat old man called Heinz who’s always there. A complete bore. We really hate him.’

‘Heinz?’

‘Yes. Jack always found him such a pain. We even tried to get a transfer . . .’

‘Bollocks. Just go. Ignore him. What’s the ballet?’

‘Petrushka.’

‘Yip!’

‘I’ve seen it before. It’s not one of my particular favourites.’

‘Go anyway. You’ve got to start forging your own path, Carrie. You’ll thank me after. Honestly.’

She’d made a special effort, with her hair and her make-up. She was wearing a dress that she’d bought for the previous Christmas. It was a glittery burgundy colour. Her lips matched. The box was empty when she arrived. She felt stupid. She sat down.

After five minutes, a couple she knew only to say hello to arrived and took their seats. They smiled and nodded at Carrie. She did the same in return. She then paged through her programme and pretended that she wasn’t overhearing their conversation about the kind of conseratory they should build on to the back of their house. He wanted a big one that could fit a table to seat at least six. She wanted a small, bright retreat full of orchids and tomato plants.

Carrie kept reading and re-reading the names of the principal dancers. The orchestra’s preparatory honking and parping jangled in her throat and with her nerves. She closed her eyes. I will count to ten. One, two, three, four . . .

‘Ooof! Here we go, here we go!’

Heinz, squeezing his way over to his seat, pushing his considerable bulk between the two rows of chairs.

‘Oi! Hup! There we are.’

Carrie opened her eyes and stared at him. He had a box of chocolate brazils in one hand and a bulging Selfridges bag in the other, which he almost, but couldn’t quite, fit into the gap between his knees and the front of the box.

Carrie’s gut rumbled her antipathy. He smelled, always – as Jack had noted on many an occasion – of wine gums and Deep Heat. An old smell. He must have been in his eighties, wore a grey-brown toupee and weighed in, she guessed, like a prize bull, at around three hundred and twenty pounds.

Carrie converted this weight into stone and then back again to occupy herself.

Heinz nodded at her. She nodded back. He always wore a sludge-coloured bow tie. It hung like a shiny little brown turd, poised under his chin.

Heinz endeavoured, with a great harrumphing, to find adequate room by his knees for his bag. ‘Uh-oh! Uh-oh!’

Carrie gritted her teeth.

‘If you haven’t room for your shopping, this chair is empty.’ She indicated Jack’s empty seat which separated them.

‘Empty? Really? That lovely man of yours isn’t with you tonight? Empty, you say?’ He wheezed as he spoke, like an asthmatic Persian feline, which made his German accent even more pronounced.

You’d think, Carrie speculated, that a wheeze would take the hard edges off a German accent, but you’d be wrong to think so.

‘Would you mind’ – close to her ear – ‘if I sat next to you and put my bag on the other seat?’

My God! Carrie thought, fixing her eyes on the stage curtains and breathing a sigh of relief at their preliminary twitchings.

‘Brazil?’

Ten minutes in, Heinz was whispering to her.

‘What?’

‘Brazil? Go on. Have one.’

‘No, thank you.’

‘Go on!’

‘No. I don’t actually like brazils. Nuts give me hives.’

Heinz closed the box and rested it on his lap.

During the intermission, Heinz regaled Carrie with tales about the relative exclusivity of the Turner and Booker prizes. He liked the opera, it turned out, especially Mozart. He found camomile tea to be excellent for sleeplessness. He was a widower of seven years.

Carrie noticed how the box’s other regulars smiled at her sympathetically whenever they caught her eye. It was odd, really, because actually, with increased acquaintance, Heinz wasn’t all that bad. In fact, if anything, he’d made her the centre of attention in the box. The focus, the axis. She felt rather like Princess Margaret opening a day care centre in Fulham.

As the safety curtain rose for the second half, Heinz was telling Carrie how he’d just been to Selfridges to buy a cappuccino maker. He loved everything Italian. He’d been stationed there during the war.

As the stage curtains closed, Heinz mopped something from the corner of his eye and muttered gutturally, ‘Poor, poor old Petrushka!’

During the curtain calls Heinz told Carrie that he often felt that it was sadder to be a sad puppet than a sad person.

‘Pardon?’

‘Petrushka, the puppet. Sometimes it feels like the ballet is sadder because he is a puppet and not a living being.’

‘Oh, right. Yes.’ Carrie finished applauding and leaned over to pick up her bag. Heinz stayed where he was.

‘How will you be getting home then, Carrie?’

‘I brought my car.’

‘Really?’

‘Yes.’

‘So maybe, maybe you wouldn’t mind joining an old man for a cup of coffee somewhere before you make your way back?’

‘Uh?’ Carrie was agog.

‘Oh! Um . . .’ She thought about it for a long moment. She imagined her quiet house, her empty bed. ‘OK,’ she said cheerfully, ‘love to.’

Sydney was late for Thursday’s class so they didn’t have a chance to chat beforehand. Afterwards though, in the sauna, they had plenty of opportunity for exchanging news. Carrie wore a white towel around her essentials and sat on the lower bench. Sydney wore nothing and sat on the upper.

‘How’d it go then?’

‘Pardon?’

‘Last night.’

‘Fine.’

‘Yeah?’

‘Yes.’ Carrie cleared her throat. ‘I mean, you know how it is when you do something alone for the first time when you’re accustomed to doing it with someone else . . .’

‘I guess so.’

Sydney lay down flat on her back. Whenever she lifted her shoulders or her buttocks, they stuck to the wooden boards, aided by the natural glue of her body’s moisture. The noise this made reminded Carrie of the sound of an emery board against a ragged nail.

‘Actually,’ Carrie said, grinning, ‘La Fille Mal Gardée is my favourite ballet.’

‘Really? You like an element of slapstick, huh?’

‘I suppose I must do.’

‘Myself, I prefer a tragedy. I find that tragedy best reflects my emotional and psychological state.’

Carrie turned and stared straight into Heinz’s frogspawn eyes. ‘You’re kidding.’

‘Me? Kidding? Not at all. Not at all.’

Heinz offered Carrie his family-size box of Maltesers.

‘Thanks.’

Carrie took one and popped it into her mouth. ‘That’s the strangest part . . .’ she said, chewing and enjoying the sensation of chocolate and malt on her tongue. ‘I’ve been to four ballets with you and never for a moment did I think you seemed like a sad or a dissatisfied person.’

It was the interval. Heinz and Carrie were propping up the theatre bar. Heinz had discovered that Carrie’s favourite winter tipple was port and lemon. He’d taken to ordering her one before the show. This meant they didn’t have to wait to be served during the intermission.

Heinz smiled at Carrie. ‘You see the best in everyone.’

‘Maybe I’m just insensitive.’

‘You? Insensitive? Never. You’re an angel.’

A man standing just to Carrie’s left turned and stared at them. Carrie caught his eye. His expression was a mixture of amusement and confusion. Carrie took a sip of her drink. People were so funny, the way they stared. Their quizzical expressions. It had begun to dawn on her that when she was out with Heinz she became a puzzle. She became mysterious.

Alone, at home, in life, she felt like something dried-up, wrung-out and innocuous. Out with Heinz, she felt like she was transformed into something much less explicable.

Heinz was bossy and opinionated but he wasn’t entirely unobservant. He rolled his eyes at Carrie. ‘Probably thinks you’re my daughter.’

Carrie shrugged. ‘And I could be too, easily.’

Carrie often found Heinz to be genuinely perceptive. At their second ballet together he’d said, ‘And your husband . . . ?’

To which she’d responded, ‘I don’t ever want to talk about him.’

‘Very well.’

And they’d never spoken about him since. It was almost like, Carrie decided, Jack had never even existed.

Sydney was plaiting her hair, trying, but failing, to include the front bang-like bits into the weave so that they didn’t keep falling into her eyes. Their class was due to start at any minute. Carrie stood behind her, scowling to herself, intensely discomfited.

‘I was only saying,’ Sydney observed, still plaiting, ‘that it seems a bit strange for you not to want me to come with you when you said yourself on several occasions that there was a spare ticket going begging.’

‘There is a spare ticket,’ Carrie said, caught distinctly off her guard. ‘It’s only that next week I promised someone else . . .’

‘Who?’

‘A friend called Sue,’ Carrie said, too quickly, and then widened her eyes when she’d finished speaking as if the words she’d just uttered were indigestible.

‘Who?’

‘I told you about her, surely? She’s the one who thinks I should open my own interior design shop.’

‘Sue?’

‘Yes. Remember? I said I was thinking about starting work again, now that Jack’s gone. The money’s tight and everything.’

‘Interior design? That’s the first I’ve heard of it. How could you afford to open an interior design shop? You don’t know anything about retail . . .’

Sydney finished her plaiting and turned to face Carrie. Carrie’s cheeks were red, she noted, and she was scratching her neck as though she’d been bitten.

‘It was just an idea.’

‘Where would you get the money from to start a business with? You’re broke.’

‘I know.’

‘Interior design, you said?’

Carrie nodded.

‘Sue? Sue who?’

Carrie blinked and then swallowed. ‘The Sue who’s coming to the ballet with me next week. We were at school together. I surely must’ve mentioned her before.’

‘No.’

People had started to filter their way gradually into the gym. Carrie pointed, ‘I think the class is due to start.’

‘OK, next time.’

‘Pardon?’

Sydney smiled. ‘Next time I want to come with you, so make sure you keep the ticket spare, all right?’

‘Yes. Fine.’

Sydney led the way. Carrie looked down at her trainers and silently incanted a Hail Mary.

They’d become so engrossed in their conversation that they hadn’t noticed everyone else going back inside. Carrie was so engrossed in what Heinz was saying that she almost hadn’t noticed his hand on her shoulder. Almost.

‘What else do I have to spend my money on? Huh? There’s nothing. I want for nothing. It would give me enormous pleasure to help you out.’

‘I don’t know.’ Carrie, for some reason, couldn’t stop thinking about Sydney.

‘Actually, Heinz, next time I come to the ballet I’ll be bringing someone with me . . .’

Heinz’s hand slipped from Carrie’s shoulder. His voice was suddenly flat. ‘Oh. That’s good. It seems such a shame to waste the seat every week like you do.’

‘Exactly. We go to the same evening class together.’

‘Does this person have a name?’

‘Sydney.’

‘I see. I see.’

Carrie noticed that Heinz’s face was pale and doughy. ‘Is something wrong?’

‘Nothing at all. Nothing.’

Carrie continued to stare at Heinz. Was he all right? He didn’t look it. She suddenly became nervous and she didn’t know why. She started to babble. ‘She’s Australian. I had to invite her. She asked.’

Heinz put his hand to his bow tie. ‘She’s a girl?’

‘Yes.’

Carrie watched with ill-concealed amazement as Heinz burst out laughing. He laughed so hard and loud that his toupee slipped. Then he plucked it from his forehead with his meaty hand, tossed it into the air with a great whoop and then caught it, just as deftly.

The sauna. Sydney sat bolt upright, her eyes as wide as saucers, each hand enfolding a single breast as though her amazement endangered them in some way.

‘You’re sleeping with this guy?’

Carrie’s towel was wrapped as tight as it could be but still she hitched it closer. ‘Not exactly. I didn’t spend the night . . .’

‘You fucked this man?’

‘Please! He’s eighty-three!’

‘Exactly! He’s eighty-fucking-three and you shagged him. My God! How did this happen? How does it happen that an attractive forty-four-year-old woman, in her prime, great body, big hair, the lot, shags an eighty-three-year-old man who she was the first to admit . . .’

‘It wasn’t . . .’

‘Who she was the first to admit is the fattest and most boring old loudmouth in the whole damn universe. How? Huh?’

‘Sydney! Please . . .’

‘Jesus, I can just imagine it.’

‘Imagine what?’

‘You know what I mean.’

‘Don’t!’

‘Guess what I’m visualizing, Carrie. I am visualizing this grey slug of a man with an enormous pale belly and a tiny penis like a party-time Mars Bar hanging down below . . .’

‘Stop it!’

Carrie was on the brink of crying. She was so ashamed. It wasn’t even the act, the fact of it, that shamed her, only Sydney’s perception of it and then her perception of it as a result of Sydney’s. That was all. And if Sydney hadn’t insisted on the second ballet ticket it would never have been a problem, she could have hidden it. She could have pretended . . .

‘He must be loaded.’

‘What?’

‘Money. Why else would you want him? Is he loaded? Is he going to, maybe, give you a little bit of money to start off your interior design business? Is that it?’

Carrie was mortified. ‘It isn’t like that at all!’

‘No? How is it then?’

‘I don’t know!’ Carrie started crying.

Sydney was unmoved. She said softly, ‘You know, I kept thinking you were taking this whole Jack thing too well.’

‘I don’t want to talk about Jack!’

‘What would Jack think, huh? What would Jack actually think if he knew what you were doing?’

Carrie stood up, covered her cheeks with her hands, bolted out of the sauna, through the changing rooms and into the showers. There she turned the tap to cold, ripped off her towel and pushed her burning face into the jet.

Sydney crossed her llama legs at the knee and then dialled Jack’s number.

‘Hi Jack. It’s Sydney.’

‘Sydney? Well, hello. What can I do for you?’

‘I want to see you. It’s about Carrie.’

After Jack had put down the phone, he picked up his duffel coat and brushed it off. He was keenly looking forward to a cold snap.

It was a nightmare. Just as she’d imagined. Heinz wore his toupee and his turd-coloured tie. He kept regaling them with terrible stories about his late wife’s beloved red setter which had died – following several years of chronic incontinence – after swallowing a cricket ball. Carrie supposed that he must be nervous. Poor lamb.

Sydney was horribly polite. She kept staring at Heinz’s stomach as she spoke to him, like she expected, at any minute, that something might explode out of it.

When Carrie drove her home, she didn’t talk for the first ten minutes of the journey. She merely said, ‘Carrie. Leave me. I have to digest.’

Carrie left her. Eventually, after she’d digested sufficiently, Sydney said, ‘He belched throughout the ballet. It was like sitting next to an old pair of bellows. Christ, the orchestra should recruit him for the wind section.’

Carrie’s heart sank. ‘He wasn’t belching. He swallowed a toffee too quickly. It went down the wrong way. He kept apologizing.’

‘And that fucking dog! His dead wife’s dead fucking dog! Does he really think I’m interested in how they fed it a diet of fresh chicken to try and quell its chronic flatulence? Are you interested, Carrie? Huh?’

‘No.’

‘Pardon?’

‘No! No, I’m not interested. I’m not.’

‘And I just can’t believe . . .’

‘What?’ Carrie tried to keep her eyes on the road, but Sydney’s expression . . . ‘What?!’

‘The two of you . . .’

‘What?’

Sydney’s eyes were glued to the road ahead. It was starting to rain. Carrie turned on the windscreen wipers just in time with Sydney’s next pronouncement.

‘Fucking.’

Carrie said nothing. They both stared at the road. Eventually Sydney turned her eyes towards Carrie. ‘Well?’

Carrie said nothing. She focused on the road and the wipers and the rain and the way that the light from the streetlamps reflected in the drops of water on the windscreen before each harsh stroke brushed it away. Where do they go? She wondered. Where do those moments go? The rain falling in just such a way, the light, the wiper. Something there and then something gone.

Sydney found she was boiling. Not hot, but something inside. What else could she do? What else could she say? Carrie had closed down, shut up, like a clam. Sydney cursed herself. She was too impetuous. Too quick to judge. If only she’d tried to be nice, to be supportive. Maybe then Carrie might have provided her with some details. Something to ponder, to mull over, fat to chew on. Damn! Sydney crossed her arms, stared at the road, boiled.

‘I got your number from the book,’ Heinz said.

‘Didn’t I give it you?’

‘No.’

‘I should’ve.’

‘She didn’t like me.’

‘No. Actually, I think she really hated you.’

‘Sometimes I can be overwhelming. It’s a fault of mine. I know that. But I am simply myself. When you get old . . .’

‘You tried your best.’

‘But did I? One tends to forget how it is to . . . uh . . . to play the game.’

‘Never mind.’

‘Can I see you?’

‘Pardon?’

‘Tonight?’

Carrie rubbed her eyes with her spare hand. ‘I only just got in. It’s raining outside . . .’

‘Tomorrow?’

Sydney lay on her stomach and rested the weight of her head on her hands. What was wrong? It was just . . . she couldn’t imagine. Carrie and that fat old man. My God! She just couldn’t picture it. Not properly. Not graphically. She rolled on to her back. Couldn’t imagine. But my Lord, my Lord, how she longed to!