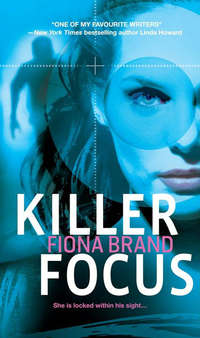

Killer Focus

Praise for Body Work

“Body Work is the kind of book that sucks you into the pages and won’t let you go until the end. It’s edgy and different, with a strong hero and heroine who don’t fit the usual mould.” —Bestselling author Linda Howard

“Brand tells a disturbing, engrossing tale of

murder and madness, adding her own unique

touches of eroticism and humour.

An excellent read.”

—Romantic Times BOOKreviews

Praise for Touching Midnight

“Brand’s extraordinary gifts as a storyteller

are very evident here. This story is a rare and

potent mixture of adventure, mystery and

passion that shouldn’t be missed.”

—Romantic Times BOOKreviews

Also by Fiona Brand

DOUBLE VISION

BODY WORK

TOUCHING MIDNIGHT

Watch for Fiona Brand’s upcoming novel

BLIND INSTINCT

Available April 2009

KILLER FOCUS

FIONA BRAND

www.mirabooks.co.uk

Acknowledgements

Once again, thank you to Jenny Haddon, a former bank regulator, for her advice and the fascinating insight into the world of international banking, Claire Russell of the Kerikeri Medical centre, New Zealand, for supplying the medical details and for helping me find the right drug to fit the crime, and to Pauline Autet for kindly answering my questions about the French language and providing the perfect phrases. Heartfelt thanks also to my editor, Miranda Stecyk, and the team at MIRA Books.

For Dad

Prologue

Portland, Maine October 12, 1984

The powerful beam of a flashlight probed the darkness, skimming over breaking waves as they sluiced between dark fingers of rock. Hunching against an icy southerly wind and counting steps as she picked her way through a treacherous labyrinth of tidal pools, a lean, angular woman swung the beam inland. Light pinpointed the most prominent feature on the exposed piece of coastline, a gnarled, embattled birch that marked the beginning of a steep path.

Breath pluming on the chill air, she followed the track to the rotted remains of a mansion that had once commanded the promontory, and which had burned down almost thirty years ago to the day.

Memories crowded with each step, flickering one after the other, isolated and stilted like the wartime newsreels she’d watched as a child. The wind gusted, razor edged with sleet, but the steady rhythm of the climb and the purpose that had pulled her away from a warm chandelier-lit room and an ambassadorial reception to this—a mausoleum of the dead—kept the autumn cold at bay.

Thirty years ago, the man who had hunted her, Stefan le Clerc, had almost succeeded. The Jewish banker turned Nazi hunter had tracked her and her father and the Schutzstaffel, the SS officer who had been tasked with caring for them, through a series of international business transactions. Somehow le Clerc, a former banker, had broken through the layers of paper companies that should have protected them and found their physical address.

Dengler had shot him, but not fatally. In the ensuing struggle, le Clerc had turned the tables on Dengler, wounding him. Then he had shot her father at point-blank range. She had had no doubt le Clerc would have killed her if she hadn’t barricaded both Dengler and le Clerc in the ancient storeroom, where they grappled together, and set it ablaze.

The fire had been terrifying, but it had served its purpose. The two men and her father’s body had been consumed within minutes. In the smoking aftermath, any evidence of gunshot wounds the skeletal remains might have yielded had been wiped out by a series of substantial bribes. The weeks following her father’s death had been difficult but, once again, money had smoothed the way and, at eighteen years of age, she had been old enough to conclude all of the legal requirements and make arrangements to secure herself.

Ice stung her cheeks as she paused by a small, sturdy shed and dug out a set of keys from the pocket of her coat. A gust flattened the stiff oilskin against her body and whipped blond strands, now streaked with gray, across her cheeks, reminding her of a moment even further in the past.

Nineteen forty-four. She had been boarding the Nordika.

She shoved the key in the lock, her fingers stiff with cold. She had been…seven years old? Eight?

She didn’t know why that moment had stuck with her. After years of heady victory, then horror, it hadn’t been significant. The wind had been howling off the Baltic, right up the cold alley that Lubeck was in the dead of winter, and it had been freezing. Aside from the lights illuminating the deck of the Nordika and the dock—in direct contravention of the blackout regulations—it had been pitch-black. After hours spent crouching in the back of a truck, sandwiched cheek by jowl with the other children, the lights and the frantic activity had been a welcome distraction but hardly riveting.

And yet, she remembered that moment vividly. A crate had been suspended above the ship’s hold as she’d walked up the gangplank, the swastika stenciled on its side garishly spotlighted, the crane almost buckling under the weight as the crate swayed in the wind. The captain had turned to watch her, his eyes blank, and for a moment she had felt the power her father wielded. The power of life and death.

Slipping the shed key back into her pocket, she stepped inside out of the wind, pulled the door closed behind her and engaged the interior locks. She played the beam of the flashlight over the dusty interior of the shed, then reached down and pulled up the hatch door that had once been the entrance to the mansion’s storm cellar. Her flashlight trained below, she descended to the bottom of the ladder, crossed a cavernous, empty area, ducked beneath a beam and unlocked a second door.

Here the walls were irregular, chiseled from the limestone that formed a natural series of caves, some that led down almost to the sea. The beam of the flashlight swept the room. It was a dank and cold museum, filled with echoes of a past that would never be resurrected and a plethora of unexpected antiquities.

A dowry to smooth their way in the new world and ensure their survival.

Moldering uniforms hung against one wall. For a moment, in the flickering shadows, they took on movement and animation, as if the SS officers they had once belonged to had sprung to life. Her father, Oberst Reichmann. Hauptmann Ernst, Oberleutnant Dengler, leutnants Webber, Lindeberg, Konrad, Dietrich and Hammel.

It was a terrible treasure house but, despite the fact that by right of her heritage she had become the custodian, she wasn’t locked in the past; the future was much too interesting.

Provided they were never discovered.

She’d studied the news reports over the years as one after the other of their kind had been cornered and killed, or imprisoned in various countries, but she was too disciplined to let emotion or bitterness take hold. She was nothing if not her father’s daughter.

Crouching down, she unlocked a safe. Her fingers, still stiff with cold, slid over the mottled leather binding of a book. Relocking the safe, she set the book down on a dusty table and turned fragile pages until she found the entries she needed. Names, birth dates, genetic lineage, blood types. And the numbers the institute had tattooed onto their backs.

The older entries, written in an elegant copperplate hand, had faded with time. The more recent additions, the false names, IRS numbers and addresses, were starkly legible.

The documentation of the link they all shared was an unconscionable risk and a protective mechanism. They were all ex-Nazis and illegal aliens; the surviving Schutzstaffel were gazetted war criminals. Collectively, they were all thieves. They had stolen the spoils of war from a dozen nations to cushion a new life, and murdered to secure it.

Every one of them was vulnerable to discovery. The agreed penalty for exposing a member of the group or compromising the group as a whole was death.

She turned to the last section of the book, and the half-dozen names noted there, and added a seventh: Johannes Webber, now known as George Hartley. It was an execution list.

Slipping a plastic bag from the pocket of her coat, she wrapped and sealed the book, which was no longer safe in this location. She would make arrangements in the morning to relocate the rest of the items, and destroy those that couldn’t be moved.

Cold anger flowed through her as she locked the door of the shed and started down the steep path, hampered by the powerful wind and driving sleet. She hadn’t used the book for almost a decade. But then, as now, the need to use it had been triggered by a betrayal. Webber, the old fool, had talked.

After all these years, the Nordika had been located.

Cancun October 14, 1984

She stepped into the foyer of a popular resort hotel, took a seat and waited. Seconds later, she was joined by a narrow-faced Colombian. Her Spanish was halting and a little rusty, but her lack of fluency scarcely mattered. Mendoza spoke English and he already knew what she wanted.

The conversation concluded, she got to her feet and left, leaving an envelope on the seat. She didn’t turn to check that the man had picked up the envelope. He was there for the money—a very large sum of money. Twenty-five percent now, seventy-five percent when the job was done. She had found that if she paid fifty percent up front, the hitter invariably took the money and ran. With the majority of the money on hold, greed guaranteed completion.

A street urchin trailed the blond gringa through the streets. She was easy to spot but not so easy to follow. Unlike most of the tourists who crowded the resort town, she checked her back every few seconds.

She entered a crowded market. Sidling close, he snatched at the large tote bag she was carrying. She spun, her fingers hooked around the strap, preventing a clean getaway. Surprised, he yanked. The strap broke and he stumbled back. She reacted with unexpected ferocity, lunging after him. Bony fingers closed on one arm, hard enough to bruise. A fist caught him in the cheek, the impact snapped his head back and made his ears ring, but he’d been hit worse, and for a lot less money. With a vicious jerk, he yanked the bag from her fingers, twisted free and darted down a side alley.

Automatically scanning the narrow streets for policia, he sprinted across the road, through a darkened, almost deserted cantina and out onto another dusty street. He could hear the gringa behind him, her heels tapping sharply on the cobbles. That was another thing that was different about her. Most women screamed and made a fuss, they didn’t chase after him.

Ten minutes later, as arranged, he met the man who had paid him to steal the gringa’s bag on the beach. Tito Mendoza was narrow faced and feral, with a reputation as a killer.

Heart pounding, avoiding Mendoza’s stare, he handed over the bag. Mendoza examined the contents, drew out a musty old book wrapped in plastic, then slipped his hand in his pocket and handed over a wad of bills.

The following evening, Mendoza stepped out of a dim, smoky bar and made his way through streets filled with strolling tourists. The beach was dark and empty, the absence of the moon making the night even darker.

He reached the rendezvous point, the shadowy lee of a rock formation, and settled in to wait, gaze drawn to the faint luminosity of the breaking waves, the empty stretch of sand. He was early, but with the money at stake, he didn’t want to leave anything to chance, and the Frenchman had a reputation for being exacting.

A faint vibration drew him up sharply. He could hear two men, not one, as agreed, and a primitive jolt of warning had him reaching for his gun.

The first slug caught him in the stomach; the second went higher. Mendoza clawed at his chest, his legs buckling. His gun discharged as he hit the ground, the round plowing uselessly into the sand.

Pain sliced through him as he was rolled over in the sand and the rucksack, which contained the book, was stripped off his shoulders. More pain as he was kicked onto his back. A spreading numbness in his legs, the fire eating into his chest and stomach.

Cold, dark eyes met his. Muerte. Death.

He must have lost consciousness; when he came to, the Frenchman was leaning over him, his palm jammed over the wound in his chest. He could hear sirens, the babble of voices.

Xavier le Clerc’s gaze was fierce. “The book. Where is it?”

Mendoza coughed, pain spasmed. “Gone.” He couldn’t breathe; his mouth kept filling with blood.

“Who took it?”

Mendoza spat a name.

Faces appeared. The pressure on his chest eased, and le Clerc melted into the shadows. Someone, a doctor, set a bag down beside him. A uniform sent an automatic chill of fear through him. He recognized Franco Aznar, a senior detective. The questions started.

The doctor muttered something sharp.

Mendoza caught the phrases, collapsed lung, lacerated intestine. The numbness was spreading. He was a dead man; he had nothing more to fear.

Choking on his own blood, he began to talk.

Ten miles off the coast of Costa Rica October 21, 1984

The anchor dropped through murky blue-green water and lodged on the reef bed sixty feet below. The rope went taut, stopping the drift of the chartered launch as it swung south, pushed by the current and a stiff offshore breeze. In the distance a fishing boat moved slowly against the chop, reeling in a long line. Closer in, another charter boat trolled for marlin and tuna.

Lieutenant Todd Fischer eased a single scuba tank onto his back, buckled up, slipped the snorkel into his mouth and flipped backward off the railing. Seconds later, the other seven members of the naval dive team were in the water, leaving Rodrigo, the charter skipper, to man the launch. After pairing off, they replaced the snorkels with regulators and began the descent, following the anchor rope down.

Minutes of patient grid-searching later, the encrusted hull of the Nordika loomed where it perched on the edge of a deep trench.

The ship had broken into three pieces. The hull had snapped in two and everything above deck had sheared off and fallen into the trench. Todd’s interest sharpened when he noted the way the steel hull had ruptured. The blast pattern was unmistakable, indicating that the ship hadn’t foundered; it had been scuttled. There was no sign of the ship’s name, but near the stern three numbers were still visible. They matched the Lloyd’s Register number for the Nordika.

Removing the lens cover from his underwater camera, he began to take photos. The visibility was poor, but all he needed was proof that the Nordika was there. Archival records compiled from an eyewitness report and the shipping records at the Baltic seaport of Lubeck stated that the Nordika had disappeared on the sixteenth of January, 1944, allegedly hijacked by SS officers just weeks before the fall of the Third Reich. The unsubstantiated report had claimed that the Nordika had been bound for South America, loaded with passengers and an unspecified cargo. Intriguing as those facts were, it wasn’t enough to spark the interest of either the coastguard or the U.S. Navy. But a report from a civilian source that Nazi war criminals had been involved with drugs and gunrunning, liaising with U.S. military personnel and using the scuttled carcass of the Nordika as a drop-off point, had been enough to make someone in the admiralty curious.

Todd’s brief was to investigate gunrunning with a possible military link, and, crazily enough, the weird slant that there was a Nazi connection even after all this time. South America was a known haven, but Todd was no Nazi hunter. Despite the fact that their information had supplied him with documents dating back to 1943, his money was on drugs, and possibly weapons, attached to a buoy or a wreck that might or might not be the Nordika.

He moved through the ship, snapping pictures. After finding no evidence of any cargo, forty years old or more recent, he swam through the blasted area and into the detached stern. The four diesels were still bolted down in the engine room, the name Wiesen Bremerhaven still legible. He took more photos, checked the luminous dial of his watch, then swam back the way he’d come. From what he’d seen, the ship was quite possibly the Nordika. The tonnage was right, and the four Wiesen diesels matched the Nordika’s specs.

He passed through the hold and swam out onto the deck area. Thirty minutes had passed. At this level he could spend longer, but with nothing more to investigate there wasn’t much point. It was possible they would do a second dive down into the trench, just in case the stash point was farther down, but that wasn’t likely. According to the charts, the trench was more than two hundred feet deep. As a stash site, it was neither safe nor convenient.

He swam around the side of the Nordika, searching for his dive buddy, Verney, and the rest of the team. Verney had followed him into the cargo hold, but he’d disappeared shortly after. None of the other divers were in sight. Mathews, Hendrickson, McNeal and Salter were supposed to be grid-searching the reef. Brooks and Downey should have been checking along the edge of the trench. He glanced at his watch again. Thirty-five minutes had now passed. At this depth they were easily good for forty. Unless he’d given the order, the rest of the team should still be working.

A diver appeared over the lip of the trench and swam directly toward him. For a split second Todd was certain it was Downey, then something wrong registered; the neoprene suit and the gear were regulation, but the mask and the tank weren’t. Adrenaline pumped. It was possible the stranger was a diver from the charter launch that had been trolling in the area earlier. He couldn’t hear the sound of the launch’s engine, which meant they could have dropped anchor nearby, but recreational diving wasn’t compatible with game fishing, especially not this far out and with the visibility so poor.

The second possibility was that the diver was one of the bad guys, protecting their drop site. Instinctively, he depressed the shutter on the camera, then reached for the knife sheathed at his ankle. The diver veered off to one side. Todd spun in the water as a second diver swam up out of the trench. A hand ripped at his face mask. Salt water stung his eyes and filled his mouth: his oxygen line had been cut. An arm clamped around his neck. He slashed with the knife. Blood clouded the water and the arm released. With a grunt, he kicked free, heading for the surface. With a lungful of air he could make twice the distance with ease.

A hand latched around his ankle, dragging him back down. Jackknifing, he dove at the man, slicing with the knife. Blood and air erupted. He glimpsed the camera as it drifted down to the seabed, the strap cut in the struggle, and he registered that the other diver had also used a knife.

Vision blurring, he grabbed the limp diver’s regulator and sucked in a lungful of air. He had a split second to register a third diver, then a spear

punched into his shoulder, driving him back against the hull of the ship. Shock reverberated through him; salt water filled his lungs. Arm and shoulder numbed, chest burning with a cold fire and his throat clamped against the convulsive urge to cough, he kicked upward.

Sixty feet above, the ocean surface rippled like molten silver. Sunlight. Oxygen.

A sudden image of his wife, Eleanor, and small son, Steve, sunbathing in their backyard in Shreveport sent a powerful surge of adrenaline through his veins. He cleared the edge of the hull.

A split second before his vision faded, he spotted Mathews and Hendrickson, floating. Distantly, he felt hard fingers close around one ankle, the cold pressure of the water as he was towed down into the trench.

Shreveport, Louisiana October 21

Eight-year-old Steven Fischer dropped the ball.

“Aw, Steve. Didja have to—”

His cousin Sara’s voice was high-pitched and sharp as Steve stumbled to a halt. It was the middle of the day in his cousin’s backyard. Despite the fact that it was autumn, the sun was hot enough to fry eggs and so bright it hurt his eyes, but that wasn’t the reason his vision had gone funny. He could see a picture of his dad, staring at him, which wasn’t right. His dad was away, down south somewhere. Having another holiday on the navy, Granddad Fischer had joked.

This time he’d promised to bring Steve back a sombrero.

Fear gripped him. As abruptly as it had formed, the picture faded, like a television set being turned off, and the tight feeling in his chest was gone.

“I’m not playing anymore.” He stared blankly at Sara, who was looking ticked. He was going home. Something had happened. Something bad.

Shreveport, Louisiana November 20, 1984

Eleanor Fischer watched the coffin as it was lowered into the grave and fought the wrenching urge to cry out.

The gleaming oak box was filled with Todd’s clothing and a few mementos that had meant something to him. Silly bits and pieces she had hardly been able to part with: a snapshot of Todd, darkly handsome in full dress uniform; a wedding photo; a disreputable old T-shirt she’d tried to throw away half a dozen times and which he’d stubbornly retrieved from the trash can; his favorite baseball cap.

Knowing that the box didn’t contain his body, and that his remains would most likely never be recovered, didn’t make the grieving any easier. She still couldn’t accept Todd’s death; she didn’t know if she ever would. A part of her expected him to come home with some wild explanation as to why he and the rest of the guys had gone AWOL, wrap her in his arms and blot out the horror of the past month.

Jaw clenched, she dropped a white rose onto the coffin lid, and gently squeezed Steve’s hand to let him know it was his turn. Steve’s rose dropped, the stem broken, the petals crumpled, as if he’d gripped it too tightly.

Swallowing the sharp ache in her throat, she hugged him close in an attempt to absorb his pain. His shoulders felt unnaturally stiff, his spine ramrod straight.

Since the day he’d come home insisting that she find out where Todd was and check that he was all right, he’d been…different. He hadn’t wanted to play with any of his friends, or swim; instead he’d stuck close to home, staying within earshot of the telephone. When they had finally heard that Todd was missing, presumed dead, Steve had simply gone to his room and had sat staring at the wall, his focus inward.

The doctor had said that children coped with grief differently from adults, but he didn’t understand that Steve had known Todd was in trouble before they’d been informed he was missing.

Commodore John Saunders handed Eleanor Fischer the folded flag that had draped Todd’s coffin, his expression grim.

This was the second ceremony he’d officiated at this week, and there were six more to go. Eight men lost at sea, nine men lost in all, if you counted the launch skipper, and none of the bodies had been recovered. When that many men disappeared on a peacetime mission, it was difficult to stop the speculation, and so far the media had had a field day, calling the incident a bungled mission.