Lazarus Rising

In retrospect it was clear during the 1980s that Australia needed broad economic reforms to taxation, the labour market, industry protection and the financial system. As well, governments had to be taken out of the ownership of business undertakings. The economic story of the ensuing 25 years was how both Coalition and Labor governments contributed to that reform task, and how in opposition the Coalition also gave crucial support to ALP reforms — a gesture never reciprocated when the ALP was in opposition. I was a major player in that saga, from both government and opposition, and many of the pages which follow contain a detailed account of that economic journey which did so much to ensure that when the global financial crisis of 2008 hit, our nation was better placed than most to withstand its ravages.

Picture Section 1

Plate 1

My parents married on 11 July 1925 at Marrickville in Sydney. They devoted their lives to the welfare and future of their four sons.

My father ‘somewhere on the Western Front’. A gas attack damaged his lungs, which contributed to his death at age 59.

Plate 2

It was a short walk from home to Earlwood Primary School. Here I am aged six, sixth from the left in the third row. World War II ended the year before.

Dad’s garage in 1954, just after going ‘one brand’. It was at the corner of Wardell Road and Ewart Street, Dulwich Hill, Sydney. I loved working there.

Plate 3

The Canterbury Boys High School debating team of 1956 (second from the left, front row). Debating gave the priceless discipline of marshalling arguments.

I played in the CBHS Second XI in 1956 (second from the right, front row). Captain Ian Sharpe, on my right, later a professor of economics, was a good leg spinner.

Plate 4

Before a family wedding early in 1955. Dad’s health was failing; he died nine months later. The Howard brothers (from left to right): Stan, John, Bob and Wal.

With Mum at my law graduation early in 1961. My hearing problem made university quite taxing. It also meant I could not go to the bar.

Plate 5

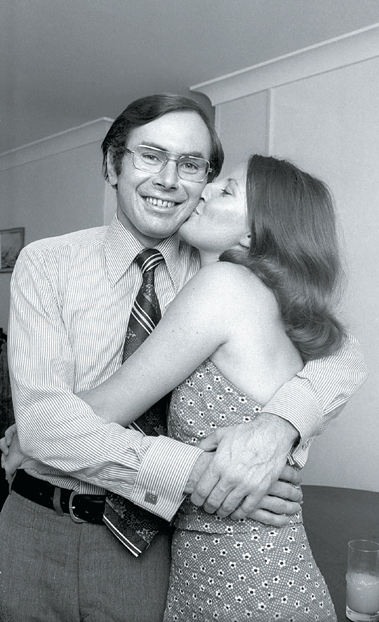

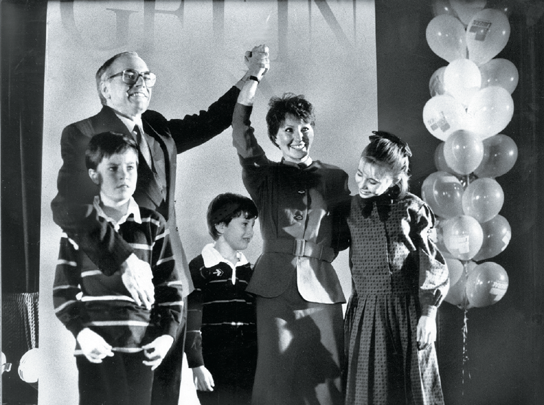

A safe federal seat: Janette and I show elation after the Liberals picked me for Bennelong in December 1973. It was a marathon day.

Plate 6

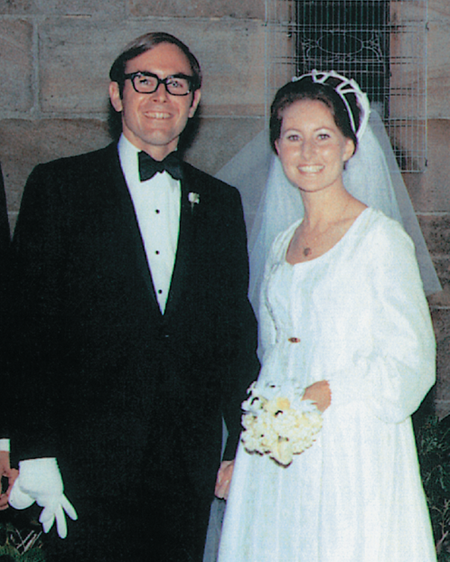

Our wedding day at St Peter’s, Watsons Bay, 4 April 1971.

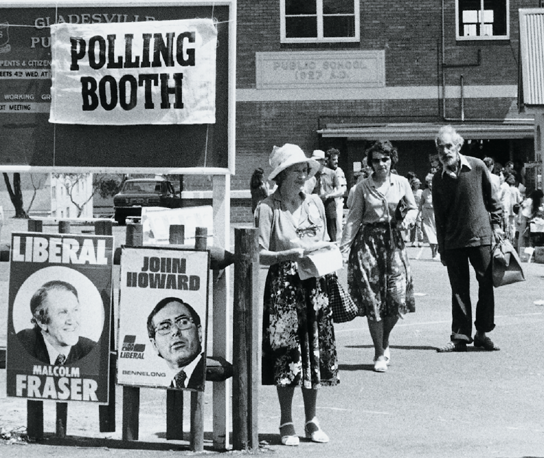

A polling booth at Gladesville Public School on election day, October 1980. Fraser’s retreat on taxation would later disappoint me.

Plate 7

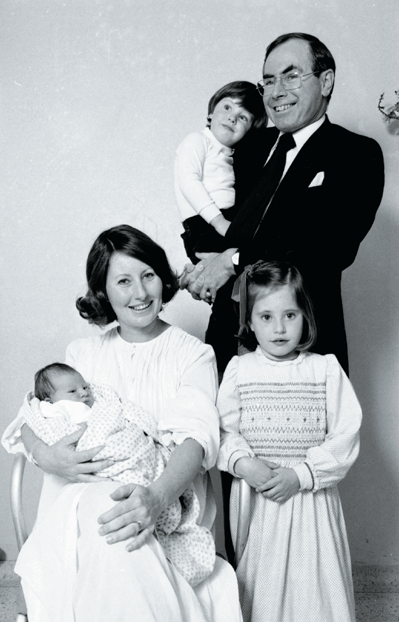

This family photo was taken after Richard’s birth in September 1980. Melanie, looking cute, is aged six. I am holding Tim, approaching three.

Plate 8

Late 1975 with Melanie and Janette on the front lawn of our Wollstonecraft home, the scene of many news conferences in the 1970s and ’80s.

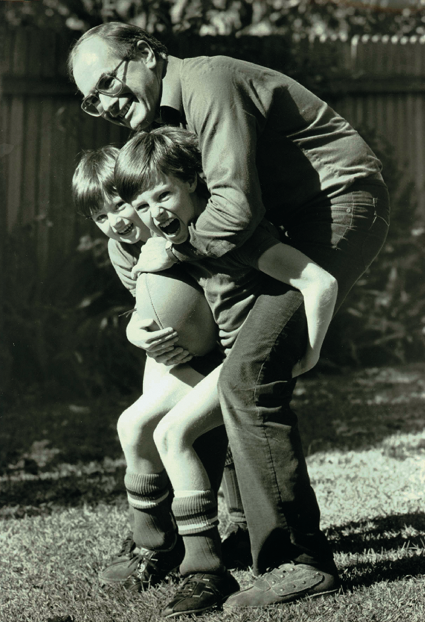

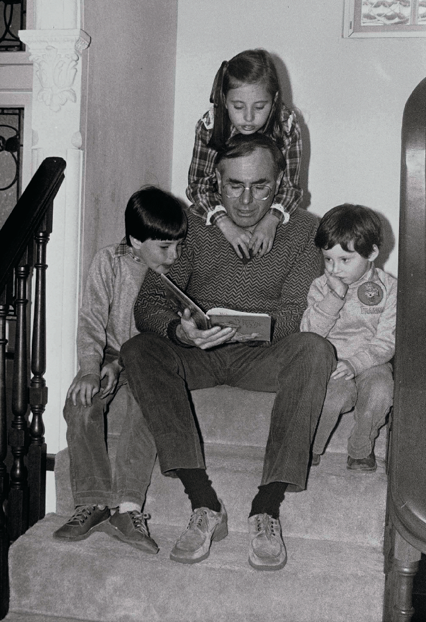

Family photos from the 1980s. Weekends were filled with the children’s activities. There was always sport.

I loved reading to them as well.

Plate 9

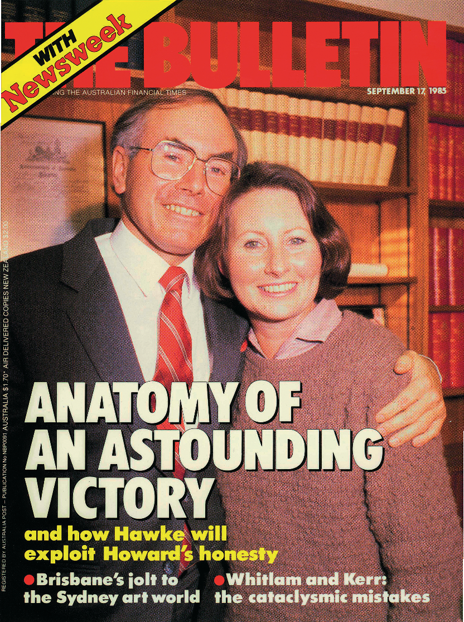

I became leader of the Liberal Party in September 1985 in amazing circumstances. The euphoria soon faded.

The Liberal campaign launch for the election of 1987 struck a real chord, but ‘Joh for PM’ made victory impossible. We didn’t pick up enough speed to win.

Plate 10

Janette and I on election night 1987. Despite a 1 per cent swing to us, Hawke won four seats.

On the verandah at Wollstonecraft in 1988. Future Directions was launched later that year. It was a clear statement of my philosophical beliefs.

Plate 11

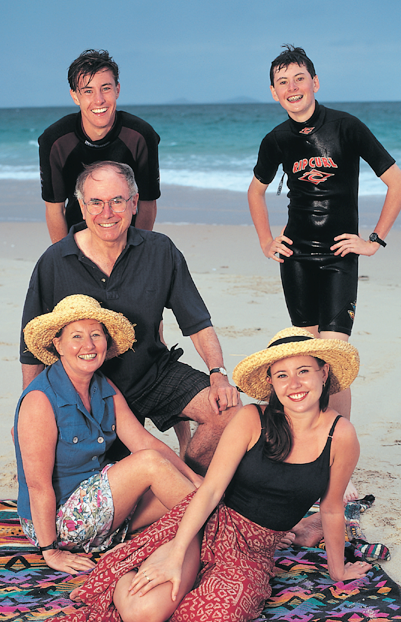

On the eve of the 1996 election, enjoying one of many family holidays at Hawks Nest. During a beach walk, the idea came to me for the Natural Heritage Trust policy from Telstra sale proceeds.

Plate 12

Election night, March 1996 — victory at last!

Watching Lleyton Hewitt’s US Open victory in the lounge room of the Australian ambassador’s residence, Washington, 9 September 2001.

Plate 13

With Richard, Tim and Janette, paying respects at Ground Zero, New York, January 2002. The raw emotion was still strong.

After my victory speech in Sydney on election night 2004. It was the Coalition’s fourth straight win. Unexpectedly, we won control of the Senate.

Plate 14

A proud father with his daughter: Melanie at her graduation from Sydney University, May 1996. All of my children took law degrees.

About to give away Melanie on her wedding day, September 2003.

Plate 15

With George and Laura Bush on the verandah of the White House before an official dinner, May 2006.

Intervarsity fencer Janette brandishes Cromwell’s sword in the ‘long room’ at Chequers. Cherie Blair and I admire her thrust but keep our distance.

Plate 16

With Melanie and my grandson, Angus, after voting on election day 2007.

Conceding defeat on election night 2007, with Richard, Janette, Tim and his future wife, Sarah. My Government left a stronger, prouder and more prosperous Australia.

14 PEACOCK VS HOWARD

In March 1983, the Liberal and National parties commenced 13 years of opposition. We would lose five elections in a row, and pass through some of the most despairing years since the Liberal Party’s foundation in 1944. The most traumatic episode would be the split in the federal coalition in 1987, forced by the overwhelming influence, within the National Party, of the Queensland Nationals, led by Joh Bjelke-Petersen, who was, for 19 years, premier of that state.

During this period we would have four leaders: Andrew Peacock (twice), John Hewson, Alexander Downer and me (twice). At the end of this long period of political exile, the party would, in coalition with the Nationals, regain office under my leadership and stay in power for almost 12 years.

Through those opposition years, I experienced just about all that could come the way of a long-serving participant in Australian politics. Yet I always retained a total commitment and sustained enthusiasm for political life. Irrespective of the position I held, I kept an unflagging interest in what I was doing. The experience of those years told me that, beyond argument, politics was my life and vocation. Some of the most productive policy work that I did in the whole time that I was a member of parliament occurred between 1990 and 1993, when I was spokesman on industrial relations for the Coalition, and my only expectation was to hold that portfolio in a Hewson Government.

Being bundled from office is a humbling experience — not that I was unprepared. The campaign had delivered a mounting realisation that there would be a change of government. The adversarial nature of politics requires one to change, almost overnight, from a reasoned decision-maker to a vigorous and informed critic of those now making the decisions. That was virtually impossible. I felt tired, both mentally and physically. What I wanted in March 1983 was a six-month sabbatical. But there was no hope of that; politics was my life.

I decided on the night of the election to stand for the leadership of the Liberal Party, made vacant by Fraser’s resignation. I knew that my only opponent would be Andrew Peacock, and that he would almost certainly win. He did, comfortably, by 36 votes to 20. As Treasurer, I was far more closely linked to the policies of the just-defeated government than Peacock. That made him a more appealing choice. I was re-elected deputy leader, and wanted a shadow portfolio away from Treasury. Doug Anthony persuaded me to stick with my old area because of my by-then-vast experience with economic issues. Fraser quietly lobbied for Andrew Peacock in the leadership contest. He did not attend the meeting at which the ballot took place, and later explained this to me on the grounds that it would not have been in my interests if I had won only narrowly, implying, unconvincingly, that he would have supported me if he had been there. I had not sought his support and, strangely perhaps, did not feel particularly offended by his attitude. Many of my friends, however, saw his behaviour as poor repayment of the loyalty I had shown to him over a long period of time.

The early weeks in opposition were very hard for me because I had to beat off claims that I had misled the public about the true state of the deficit. It was right on the eve of the election that I was given a figure of $9.6 billion as the likely deficit for the following year, which was much higher than the stab-in-the-dark figure I had casually mentioned to some journalists. Moreover, the $9.6 billion was only a starting point, and would be reduced in the normal budget process. This did not stop Bob Hawke and Paul Keating, his new Treasurer, making a huge issue of it. This was their honeymoon; the press swallowed their lines and I took quite a shellacking.

Andrew Peacock and I were rivals for the leadership of the Liberal Party for some years, but this did not, as many have argued, completely paralyse the Liberal Party in opposition. Rivalry between key figures in political parties is commonplace. From 1986 onwards, the rivalry between Keating and Hawke within the governing Labor Party was barely disguised, periodically spilling into the public arena. Nonetheless, Andrew’s and my rivalry was real, both as personalities and on policy issues.

In the culture of the Liberal Party, Andrew and I were almost born to be rivals. We were only a few months apart in age. When it seemed, to many people, to matter a lot more, he came from Melbourne and I came from Sydney. He had taken over the seat of Kooyong from Sir Robert Menzies, the great hero of our party. We were of different personalities and styles. Andrew’s urbanity and very considerable personal charm had won him early notice as a future leader of the Liberal Party. He had been a very effective minister in the McMahon Government, and had won a lot of deserved praise for the relationships he established with key figures in the newly independent Papua New Guinea. It was so easy, given our contrasting styles and personalities, for commentators to paint him as emblematic of the progressive side of the Liberal Party, and me as a dull, dogged conservative.

I respected Andrew Peacock’s diplomatic and public relations skills, but I never thought that he had deeply held policy views on more important economic issues. That influenced my attitude towards him, especially after he became party leader.

There was fault on both sides. I don’t think Andrew ever understood the depth of feeling about his resignation in 1981 and the damage that many of his colleagues believe it inflicted on the Fraser Government. As for me, I don’t think I fully understood the extent to which my continuing ambition to be leader of the Liberal Party was so apparent to colleagues, and others, from the time that Peacock defeated me for the leadership after the 1983 election.

I suspect that the last thing Andrew Peacock wanted in early opposition days was an intense debate about the philosophical direction of the Liberal Party on economic policy, especially industrial relations. Yet that is what he got, because of my determination that the Coalition should take a more consistent pro-market approach. It was, even more importantly, an unavoidable debate because the Hawke Government threw off its old Labor garb and, on issues such as financial deregulation, surprised many by going further than would ever have been expected from a Labor Government.

I never lost my ambition to lead but decided to put it on hold, and resolved to do everything I could to argue the policy positions which I held. I would perform as well as I could as deputy leader and essentially through the prism of my strongly held economic opinions.

Having been frustrated by Fraser’s opposition to certain economic reforms in government, such as taxation, I was determined not to go quietly in opposition. When the opportunity presented itself, I took a strong market-centred economic position. Sometimes this was in advance of the party’s position and annoyed Andrew Peacock and others who, for a combination of political and other reasons, might have thought that a quieter approach was appropriate.

The quiet approach was not really an option. The dynamic had changed quite rapidly since the election of the Hawke Government. The Liberal Party was under a double pressure to have a clear position on economic issues. Not only did altered world economic circumstances require different responses, but the new ALP Government was not behaving like the Whitlam Government, or indeed consistent with the commitments it had made in opposition. It had assumed the mantle of economic responsibility. This put real heat on the opposition.

Many of the Coalition’s traditional supporters in the business community began to like what they saw of the new Government, particularly when it floated the dollar and decided to admit foreign banks. Comments such as ‘the best free enterprise government we’ve had’ began to be uttered at boardroom lunches attended by opposition spokesmen. The Liberal and National parties ran the risk of being left behind if the Coalition did not sharpen its thinking on some key economic issues.

In some cases this meant agreeing strongly with what the Hawke Government had announced. In other cases it involved adopting a new policy position likely to win business support, and which the ALP would be unable to match. This made my campaign to change our industrial relations policy so important. Here, I felt, was a policy change which would win wide, but by no means unanimous, business support and which Labor, with its trade union base, could never match.

The farmers, the miners and, crucially, small business would support a new industrial relations system. Many manufacturers, however, were still wedded to the old centralised system. They felt they could live with it. In any event I was told they could ‘talk to Hawke’ if things got out of hand. The corporate state, Australian-style, was already in full bloom.

My aggressive push for policy change aggravated some colleagues. They didn’t share my sense of urgency about the need for policy revision; they thought that some of my prescriptions were too edgy, and I thought they were altogether too complacent about the solidity of our political base. A party needs more votes than its base can deliver so as to win an election, but unless its base is energised, as distinct from just mildly supportive, it has no hope of victory. Big business had been partly mesmerised by Hawke, so I saw the preservation of our small-business base as absolutely critical to our longer-term hopes of revival. Internally difficult though it was, I believed that we had to confront hard policy choices early on.

I loudly supported the Hawke Government when the dollar was floated and exchange controls abolished in December 1983. This was overwhelmingly the right policy response for the future benefit of the Australian economy.

On the morning of the day the decision was taken, the Treasurer announced the closure of our foreign exchange markets, a clear signal that the Government intended to float the dollar. That morning, Liam Bathgate, Doug Anthony’s chief of staff, showed me a press statement Doug proposed issuing, strongly attacking the floating of the Australian dollar. Liam knew that Doug’s views and mine were different, and he did not want public disagreement between us. I immediately raised the matter with Doug and we had a heated debate, totally disagreeing on the desirability of the float. In the end he acceded to my view and did not issue the statement. Floating the dollar was the ‘big bang’ of financial deregulation. Our differences on the issue symbolised a deep divide in Coalition thinking on economic policy. Fraser later attacked the float.

The Coalition’s clear support for such a huge policy decision was critical to winning acceptance for the change in the general community. It meant that as time went by and fluctuations in the value of the dollar inevitably occurred, hurting some and rewarding others, a cheap fear campaign blaming the float could not have been credibly mounted. In sharp contrast, such unconditional bipartisan support on a big policy issue was never forthcoming from the ALP during the years of the Howard Government.

Floating the dollar had more influence than any other decision taken by either the Hawke or Keating governments. Although Paul Keating is often given the credit for floating the dollar, his timidity on the issue was overridden by the Prime Minister, with the strong support of the governor of the Reserve Bank, Bob Johnson.

In its first budget the Hawke Government brought in an assets test for the payment of the aged pension. I thought this was good policy, although politically unpopular. I was absent on a brief holiday with my family in the snowfields when the shadow cabinet discussed the Coalition’s attitude to the proposal. The following day I read in the newspapers that the opposition would oppose the assets test.

If I had been present at the shadow cabinet meeting I would have argued that we support the Government. I wasn’t there and, by coincidence or not, a decision on this issue was taken. I had no alternative to going along with it, even though I felt uncomfortable.

Politically, it turned out that Peacock’s judgement on this issue was absolutely correct. His opposition to the assets test was a major reason why the opposition performed much better in the premature 1984 election than many expected. He developed a fine line of rhetoric, and it resonated with many older voters. It was a very good example of successfully applying the politics of consolidating one’s base of support, albeit in a different manner from what I was endeavouring to do with small business.

On 19 June 1984, Phillip Lynch died at the very early age of 50. Some time before, he had been diagnosed with stomach cancer. Lynch had been a hardworking servant of the Liberal Party, and had carried much of the grinding work of building the case of economic mismanagement against the Whitlam Government throughout 1975. We had been close as colleagues, and I felt for his wife, Leah, and their three sons. I called to see him at his home on the Mornington Peninsula only a few weeks before his death. He knew his fate, but was sustained by his strong Catholic beliefs. I admired his fortitude. He did not seek pity; rather he remained deeply engaged about the challenges then facing the Liberal Party.

The opposition languished in the opinion polls all through 1984. Six days before the election was called, the Morgan Poll in the Bulletin showed Hawke at 73 per cent against Peacock’s 15 per cent on the preferred prime minister rating. This probably encouraged Bob Hawke to call an election for December that year, only 20 months after his win in March 1983. He was to get a rude shock. He entered the election campaign with supreme confidence, believing that the Labor Party would win seats from the Coalition, particularly in Victoria. As a measure of his hubris, he programmed a 55-day campaign, which was ridiculously long, especially as the election was being held so soon after the change of government.