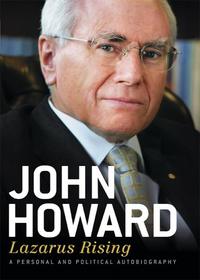

Lazarus Rising

He gave vent to those feelings about the Family Law Bill, and the roles of Whitlam and Murphy relating to it, in no uncertain terms. It was late one night, in a discussion also involving Ralph Hunt, the Country Party MP for Gwydir, who had similar reservations about the effects of the bill to mine. The three of us met in Stewart’s office to discuss a tactical approach to the debate on the measure. Stewart was deeply angered by Whitlam’s open support for the bill, being particularly incensed that the PM had himself introduced the bill into the house, instead of leaving it to Murphy’s representative, Kep Enderby. Sarcastically, he declared that Whitlam had even done the introduction ‘in a dinner suit'. No doubt Whitlam was dressed for a formal occasion, but I could see the point Stewart was getting at: the PM had an eye for the theatre of things, and would not have minded one bit being in formal wear when introducing this controversial bill.

The bellwether vote on the bill was a committee amendment moved by Bob Ellicott, the Liberal MP for Wentworth, which effectively aimed to increase the period of separation as the sole ground of divorce from one year to two. There were other changes proposed, some of which succeeded, including one from Malcolm Fraser which sought to protect a woman who wished only to continue her role as a wife and mother. But the Ellicott amendment symbolised the divide between those who thought that the bill went too far and those who did not. I voted for the Ellicott amendment. So did Paul Keating and Malcolm Fraser. Naturally Whitlam voted against it, as did the two former PMs still in the house, John Gorton and Bill McMahon. It was defeated by just one vote: 60 to 59. Thus came to pass a huge change to our divorce laws, untrammelled even by quite moderate concerns not to change too much too quickly.

A two-year period of separation as the sole ground for divorce, replacing the old multiple-fault provisions, would have constituted a profound modernisation, without the signal the bare 12-month period sent, that marriage mattered somewhat less than used to be the case. More than 30 years later, it is hard to dispute the fact that marriage has been weakened as the bedrock institution of our society. It is at least arguable that the Family Law Act has played a part in this process.

8 FRASER TAKES OVER

As 1974 wore on, the grass around Bill Snedden, the Opposition leader, had become drier and drier. There was natural loyalty to him. We all saw him as the good bloke, and wanted desperately for him to succeed. Yet, especially amongst the more recent arrivals as MPs, there were mounting doubts that he could effectively exploit growing concern in the community regarding the economy, and fix Whitlam with the necessary degree of responsibility for it. Snedden’s strongest support came from amongst longer-serving members and senators, who had gone through the pro- and anti-Gorton upheaval three years earlier. Many of them had had enough of leadership stoushes, and in the absence of a Messiah were content to stay with Snedden.

To me, and many others, Malcolm Fraser was the logical alternative to Snedden, but he was a deeply divisive figure, largely because of the part he had played in Gorton’s downfall. There were still plenty of Gorton supporters whose organising principle was not the return of Gorton to the leadership, but to keep it away from Fraser. There were some ideological drivers: people like Andrew Peacock and Don Chipp, identified as progressives, labelled Fraser too conservative and backed Snedden. That also kept open Peacock’s own aspirations for the leadership, should Snedden fall over.

Snedden’s support base also included people with very conservative stances on issues such as South Africa and Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe); John McLeay and Don Jessop, both South Australians, were firmly in this group. It was another reminder that one should not over-simplify the use of philosophical labels when it comes to the choice of a leader. In the end the dominant influence is always who is more likely to deliver victory. Ultimately, that led to Snedden’s replacement by Fraser.

Tony Staley, a Victorian MP, was Malcolm Fraser’s principal spear carrier. In his first attempt to topple Snedden, in October 1974, he was joined by Eric Robinson, MP for the Gold Coast seat of McPherson; John Bourchier, MP for Bendigo; and Peter Drummond, a farmer MP from Western Australia. Staley and his group were ridiculed for the tactics they employed. They openly waited on Snedden and told him that he should stand down in the interests of the party. There were strenuous denials of any involvement by Fraser in the actions of Staley’s group. It was easy to accept that Staley was the prime mover; he had been actively touting for Fraser for some time. It seems implausible that Fraser knew nothing at all of what was to happen when Staley’s group went to see Snedden.

Although there were predictable cries of treachery and disloyalty about the behaviour of Staley’s group, it was quite the reverse. They had been very open, having directly confronted Snedden with their concerns and asking him to resign. Naïve it might have been, but it was not treasonable.

At a party meeting late in November 1974, Staley moved a motion to declare the party leadership vacant. A clumsy attempt was made by some of Snedden’s supporters to prevent a secret ballot. One of them even called out, ‘Let’s see the dogs.’ The spill motion was lost, but the figures were not announced. I understand that this was the last time that the practice of not publicly disclosing numbers was employed by the Liberal Party. It was open to all sorts of mischief. Snedden’s supporters put around the story that he had won overwhelmingly. He had not. The vote was probably 36 to 26 in support of Snedden. I deduced from widespread discussion with colleagues in both houses that a majority of the Liberal members in the house had voted for a spill, a very clear sign that Bill Snedden’s days were numbered. I voted for Staley’s spill motion.

From then on the leadership issue was never far below the surface. The grass didn’t get green again until the change to Fraser in March 1975. It had remained tinder-dry over Christmas of 1974, which was dominated by the devastating Cyclone Tracy, which flattened Darwin and claimed 71 lives.

Whitlam’s breathtaking arrogance was on full display. He was on an extended overseas trip when the cyclone hit. He came home, went to Darwin and announced the Government’s response and then resumed his overseas visit, as if nothing had happened.

During this time, some absurd attempts were made by some of Snedden’s supporters to obtain a public undertaking from Fraser that he would not challenge for the leadership. The ridiculous word game further weakened Snedden. Fraser owed it to the party to be available, if it wanted him.

Snedden was also weakened by his dismal parliamentary performances. One of them involved him calling out ‘woof woof’ to Whitlam, to which the Prime Minister replied, ‘The Leader of the Opposition is going ga ga.’ It was one of those parliamentary moments when a short exchange alters the whole dynamic of the chamber, and is perceived to have wider significance.

But it was Andrew Peacock who struck the match that set that dry grass alight. Asked one of those interminable questions about the leadership at Adelaide Airport on 14 March 1975, Peacock flicked back the response that, ‘Rumours and divisive speculation about the leadership are doing great damage to the Party. Mr Snedden should call a meeting and ask for a vote of confidence so that speculation can be ended.’1 Peacock’s intervention surprised many. He was a Snedden man. Fraser’s camp was ecstatic. Another vote for the leadership now had to be held.

Facing the inevitable, Snedden called a party meeting for 21 March.

The motion to declare the leadership of the party vacant was carried by 36 to 28, and Fraser was elected leader by 37 to 27. It was the right decision, as events over coming months were to show. During that time, Fraser was to demonstrate a steadfast pursuit of a given objective unmatched at any other time in his career. He also changed the mood of the party immediately. Although there was plenty of residual affection for Bill Snedden, and continuing lack of warmth towards Fraser from many colleagues, the mainstream of the Liberal Party knew that it had done the right thing by going for Fraser. He sounded strong and looked like a winner.

Although Fraser and I talked regularly, both of us believed the opposition should have sharper policies, and I had made some impact as a debater in the house, I had no expectation of promotion under Fraser. It was a complete surprise when he asked me to be opposition whip. It took me all of two seconds to say yes. I was bowled over to have any job, knowing that if I did it well, other things could follow.

Politics is a very competitive profession. The golden rule, if you want promotion, is always says yes when the leader offers you a job. If you don’t then the leader is entitled to, and will, move on to someone else.

In 1997 as Prime Minister, when doing a reshuffle, I offered Petro Georgiou, the MP for Kooyong, a position as a parliamentary secretary. He knocked it back, implying that it was beneath his dignity, saying ‘I’m too old and ugly to be a parliamentary secretary.’ This was several years before refugee and asylum-seeker issues were under debate, so Petro did not reject the job on policy principle. Whatever his motives, it was a foolish response. I never offered him another job. Brendan Nelson, Malcolm Turnbull and Tony Abbott all started off as parliamentary secretaries; each was made a cabinet minister by me. All of them would ultimately lead the party. Who did Petro imagine he was?

My surprise at being offered the whip’s responsibility was exceeded just two days later when Fraser rang to say that he now wanted me to be the shadow minister for consumers affairs and commerce. The reason was that Bob Ellicott, to whom he had offered the job, had refused Fraser’s edict that shadow ministers not do any non-parliamentary work. Ellicott had wanted to keep his hand in at the bar with a small amount of legal work. His position was quite reasonable. I certainly reserved the right, in opposition, to keep my hand in at the law. There was a double standard here. Apparently it was in order for people like Fraser and Tony Street and many others to own farms, or for Eric Robinson to maintain a string of sports equipment stores throughout Queensland, but Ellicott couldn’t do some legal work.

The distinction drawn at the time was that there was a manager in charge of the farm or the business. Of course, the principal had no contact with the manager, nor did he take any interest in what happened to the asset!

In any event, Ellicott had the most eloquent precedent of all on his side. Menzies had kept taking briefs, even as Leader of the Opposition, maintaining that it kept him in touch with changes in the law. He was also not ashamed to admit that he needed the money. Before too long Ellicott had made his point; he and Fraser cobbled together some formula and he came back to the shadow ministry.

Nevertheless, Ellicott’s temporary absence from the Coalition frontbench was a huge stroke of good fortune for me. Not only was I to speak for the opposition on a wide range of business issues, including competition law, but also to represent the shadow attorney general, Ivor Greenwood, in the lower house. At the time there was an avalanche of legislation in the AG’s area, and I would, within a little over 12 months of entering parliament in the lower house, have carriage on behalf of the opposition of some of the most complicated bills of the Whitlam Government’s second term. It was a fortuitous opportunity, which I relished.

9 THE DISMISSAL

When Fraser became leader, he cancelled the standing threat Snedden had made to block supply, at the first appropriate opportunity. He said that the Government should not be forced to an early election unless there were ‘extraordinary and reprehensible circumstances'. In the light of what unfolded later in 1975, there was some scepticism about how genuine Fraser had been in withdrawing the early-election spectre. It was generally well received, as there continued to be a strong sense in the community that whatever doubts there might be about the competence of Whitlam and his team, they were entitled to a fair go, and that the threat to block supply which had precipitated the May 1974 double dissolution had been unreasonable.

Whatever his motives, and I believed that Fraser was genuine, his decision was clever politics. The consequence was to put the spotlight more sharply on Whitlam and his crew, precisely when their decline into chaos began to gather momentum.

The disintegration of Gough Whitlam’s Government was very public. Disunity in government is usually caused by perceived or real challenges to its leadership, or arguments over policy direction or a combination of the two. Neither was the case in 1975.

Whitlam remained a messianic figure to the Labor faithful; he had brought them to the Promised Land, and no matter what political disasters befell the Government, he would remain in charge.

Gough Whitlam, though, did have a vicious streak, which was demonstrated when he cut down the speaker, Jim Cope, on the floor of the house. Cope had named Clyde Cameron, the Labour and Immigration Minister, for defying the chair. Whitlam delivered a humiliating vote of no confidence in Cope by refusing to support the removal of Cameron after he had been named. Cope resigned on the spot. It was dishonourable treatment of a man who had given years of service to his party.

Cope had a keen sense of humour. Ballots for a new speaker are secret, with each member writing on a voting slip the name of the candidate for whom they intend to vote. The Liberal candidate in the ballot following Cope’s removal was Geoff Giles, the MP for Angas in South Australia. He had no hope against the ALP nominee, Gordon Scholes, and in the course of the ballot Jim Cope called out, in his piercing voice, ‘How do you spell Giles?’ It broke up the whole place.

The public beheading of Cope was but one example of Labor’s progressive fragmentation through 1975. When Whitlam reshuffled his team mid-year, Clyde Cameron noisily resisted removal from his beloved Labour and Immigration post. During a division on a bill I was handling in the Attorney General’s area, a very agitated Cameron worked on a document as he sat beside the Attorney General at the table. The Attorney said to him, ‘Think of the party, Clyde'. Cameron’s salty reply made it plain that all he wanted to do was pay out on Whitlam. It was impossible for us not to notice such unhappy division. They no longer seemed to care.

Not only was Whitlam’s big-spending and permissive approach to public-service wages growth aggravating the rising inflation and higher unemployment which had become a feature of the Australian economy, but the suspicion grew that there was something irregular, even improper, about the Government’s efforts to borrow money abroad for national development purposes.

The genesis of that suspicion was a meeting of the Federal Executive Council at the Lodge on 13 December 1974. It was an ad hoc meeting which emerged from a ministerial discussion involving Whitlam; the Deputy PM and Treasurer, Jim Cairns; the AG, Lionel Murphy; and Rex Connor, Minister for Minerals and Energy. The meeting authorised Connor to borrow up to $4 billion. The Governor-General was not at the meeting and did not know of it until the next day, itself highly unusual; the loan was described as being for temporary purposes when so clearly it was not. Under the financial agreement, overseas borrowings other than for defence and temporary purposes required the approval of the states through the loan council. It was also unusual that authority was given to Connor to undertake the borrowing; Treasury normally handled such matters through well-established and reputable channels.

The Government was never able to shake the impression of irregularity, especially when evidence emerged of dealings with fringe international financiers such as Tirath Khemlani, a Pakistani commodities dealer. When Australia had borrowed before, Morgan Stanley, a solid Wall Street bank, had usually done the work. Treasury could not understand why such a reliable path would not be followed again.

Labor’s new Treasurer, Bill Hayden, was an outpost of sanity: bright and economically sensible. If he had been there from the beginning, things might have been different. Hayden’s tragedy was that Labor was beyond the point of no return when he brought down his budget in August 1975. Its principal legacy was that of Hayden’s reputation. He came out of 1975 as by far the most credible figure in the Labor Party.

There was a steady drip of press stories, keeping alive the sense of chaos, even scandal, which surrounded the Government. Hayden’s budget was well received, but could not disperse the fog enveloping Whitlam’s team. By September the mood in Liberal ranks had hardened. Many began to argue that the Government was so bad that we had an obligation to force an early election. Remembering what Fraser had said in March, they claimed that the continuing loans saga amounted to ‘reprehensible circumstances’ and that the Coalition would be justified in blocking supply to force an early election.

The Loans Affair, as it became known, ultimately claimed the scalps of both Cairns and Connor. Cairns finally went in July, when it emerged that, despite having denied it to parliament, he had signed a commission letter to a Melbourne businessman. Connor’s resignation on 14 October was the final straw for the opposition; he had continued negotiations with Khemlani after his authority to do so was revoked.

Media pressure grew — typical being a front-page editorial from the Sydney Morning Herald, on 15 October, headed, ‘Fraser Must Act'. He did. That very day Fraser announced that the Coalition in the Senate would vote to defer a decision on the supply bills until Whitlam agreed to have an election. The next day the opposition used its numbers in the Senate to achieve this. The bills deferred were routine ones authorising the spending of moneys on the ordinary annual services of government. If the bills were delayed indefinitely, the Government would run out of legally available funds and the business of government would grind to a halt. In political and constitutional terms, it was the nuclear option. Supply had never been refused or delayed before; there had only been the threat of it in 1974. Then, Whitlam countered with an election. He would not do this in 1975.

Just before his announcement, Fraser assembled the entire shadow ministry, tabled his recommendation that the opposition vote to defer supply, and one by one he asked each shadow his or her view. Along with every other shadow present, I supported Fraser’s recommendation.

This should be recalled, as revisionism about 1975 has included suggestions that Malcolm Fraser had acted unilaterally on the supply issue. There was no dissent in the shadow cabinet ranks. Don Chipp, later to resign from the Liberal Party, form the Democrats and denounce the blocking of supply by Fraser, was one of those present at the meeting who strongly backed his leader’s position. There was enthusiastic support for Fraser’s push at the full Coalition party meeting, immediately following shadow cabinet. The late Alan Missen, a Victorian senator, was the only person to express concern. He stood and said, ‘Leader, you know I have qualms about this.’ Phillip Lynch, the Liberal deputy, replied, saying, ‘Alan, let’s have a talk about it.’ They left the room together. A short while later Lynch came back and said that ‘Everything [would] be okay'. Missen voted with the rest of his colleagues to defer supply.

Labor was understandably bitter at the failure of the Bjelke-Petersen Government to follow normal custom and replace the deceased Queensland ALP senator Bert Milliner with his chosen Labor replacement, Mal Colston. The Labor Party was foolishly stubborn in rejecting the initial request of the Queensland Premier to submit three names from which a choice would be made.

The upshot was that Whitlam was left with only 29 senators supporting him against 30 from the Coalition when the crucial Senate vote to defer supply was taken in mid October. Patrick Field, Bjelke-Petersen’s chosen replacement for Milliner, did not participate in the vote, but this did not alter the fact that if normal practice had been followed, the vote would have been tied at 30 each and supply blocked rather than deferred.

Several months earlier, the NSW Coalition Government had likewise chosen Cleaver Bunton, an Independent, to replace Lionel Murphy, who had been appointed to the High Court. This did not have the same consequences as the Queensland appointment because Bunton voted with Whitlam on the supply issue.

In 1977 the Australian people voted overwhelmingly for a constitutional change, effectively guaranteeing that when a casual vacancy occurred in the Senate the replacement would come from the same Party as the former senator.

Unlike May 1974, Whitlam did not call an election. He was determined to prevail, asserting that as governments were formed by the party having a majority in the lower house, the Senate had no right prematurely to terminate a government so formed by forcing an early election. Politically, he had no option. He would face annihilation at an early poll. Fraser’s biggest challenge was to hold the Coalition together as the weeks of deadlock dragged on.

His argument was as simple as Whitlam’s. Our Constitution gives coextensive powers to the Senate and House of Representatives, so the government of the day needs the approval of both houses to spend money. As the Senate had not given that approval, the Government could not continue to function and should call an election to resolve the issue. Politically, Fraser had to maintain his position. He knew that he would win an early poll, just as Whitlam knew he would lose it. Stripped of rhetorical excesses, it was a titanic clash of political wills between two determined men. A compromise was never likely once the Senate had deferred supply. Fraser did offer to pass supply if Whitlam agreed to hold an election the following May. This was rejected.

Once the two protagonists had staked out their ground, interest focused on who might blink first, and increasingly, as the weeks passed, how or when might the Governor-General act. Whitlam’s operating assumption was that Kerr would always do as he was told. He badly misread his choice as Australia’s effective Head of State. Kerr would be no cipher. No one understood this better than John Carrick. In the days that followed the deferral of supply, he said to me several times, ‘John Kerr will want the judgement of history. He will do the right thing by the office.’ Carrick had known Kerr for a number of years, and well enough to divine that he was not in any way beholden to the Labor Party.

John Kerr was called ‘Old Silver’ at the Sydney bar because of his impressive mane of white hair. Bob Ellicott knew him well. They had been barristers together. He shared Carrick’s opinion that Kerr would want to be seen as having done his Constitutional duty. On 16 October, Ellicott published a prescient legal opinion of what Kerr might have to do; in it he raised the option of dismissal of Whitlam and his ministers as a way through. In a drama which involved many lawyers (mostly from the Sydney University Law School), Ellicott emerged, courtesy of this opinion, as the real star.

Tirath Khemlani, the Pakistani commodities dealer who had been put in touch with the former Minerals and Energy Minister Rex Connor when the latter was on the hunt for overseas loan moneys, landed in Canberra in the middle of the imbroglio, wanting to see the opposition. Ellicott and I were given the job of talking to him and getting details of his contact with Connor. It was disconcerting; if Australia wanted to borrow large amounts of money for development purposes, it beggared belief that it would not act through traditional banking channels. Khemlani was at most a fringe operator, and Connor’s behaviour had made Australia look foolish. Bob Ellicott and I found Khemlani a likeable man when interviewed at the Wellington Hotel, Canberra, but we didn’t see him and Australia borrowing abroad as a natural fit.