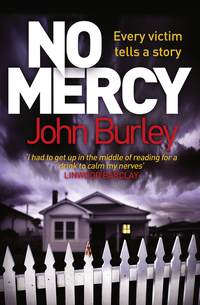

No Mercy

‘Sheriff’s Department, ma’am.’

A momentary pause, followed by the sound of the voice, already afraid, calling out to someone deeper inside of the dwelling: ‘They say it’s the Sheriff’s Department.’

A man’s voice, descending down the interior stairs: ‘Well, what do they want? Jesus, Martha, open the door!’

The sound of the dead bolt sliding back within its metallic housing. The door slowly swinging open to reveal a man and a woman, roughly the same age as Susan and himself, standing just inside the open threshold and looking out onto the cold, gray world and the unfortunate messengers standing in front of them. In this image he has conjured, the couple suddenly appear frail beyond their given years, as if this moment itself has weakened them. In a timorous glance, they take in the grave faces of the two unwelcome men standing before them, who have arrived with news the parents do not want to hear, and whose expressions carry within them all of the information that really matters: I’m terribly sorry. Your boy is gone. He was left dead in the woods, and he lies there still while we try to figure out who might have done this to him. He will never walk through this door again.

In that moment, standing in their own driveway with familiar gravel beneath their feet, Ben offered a silent prayer of gratitude – God forgive him – that he and his wife had not been selected at random to receive that horrible message. It was a prayer of relief and thankfulness for the safety of his family, and a prayer of compassion for the ones who waited even now for the messengers to come.

‘Let’s go inside,’ he whispered to Susan, and the two walked up the steps together.

Chapter 3

An hour later, the three of them stood on the sidewalk, impatiently awaiting the arrival of the Indian Creek High School bus. A block to the east, the sound of passing vehicles could be heard as they traveled along Canton Road on their way north toward Route 22. Beside him, Susan fidgeted restlessly. Ben shared the sentiment. A recorded message from the high school baseball coach, after all, could only go so far in placing a parent’s mind at ease.

Ben glanced at his watch. It was seven o’clock. Shouldn’t the bus be here already? he wondered. Perhaps not, considering the traffic and events of the day. Rounding everyone up and making sure that all of the kids were accounted for would take longer than expected. Some of the parents would just now be arriving home from work, and there would be no one waiting to receive the kids at certain stops. It could be another hour, he realized.

Dusk was already beginning to settle upon the neighborhood. In another forty minutes they’d be standing here in the dark. Under the circumstances, he reflected, it was probably not the best plan the school could have come up with; a bunch of families standing around outside in the dark waiting for their kids to be dropped off while somewhere out there a psychopath roamed the streets. He thought about returning home for the car, even though they lived only two blocks away. He didn’t want to leave Susan and Joel standing here alone, however, and he was afraid that if they all went back together the bus would arrive during the time they were gone. Instead, they waited, watching their shadows grow long and lean as the sun continued its rapid descent toward the horizon.

Something the size of a large cicada moved against Ben’s upper leg with a soft buzzing sound, startling him. He nearly cried out, but in a moment it was gone. He shuddered involuntarily, imagining its crunchy, crackling exoskeleton flitting up against him.

Suddenly, it came again, nestling up against his right thigh with a muffled burring noise. He leaped backward. ‘Shit! What was that?’

Susan looked over at him inquisitively, eyebrows raised. ‘What’s wrong with you?’

‘A giant bug just hit me in the leg,’ Ben advised her. ‘Twice!’

No sooner had he uttered these words than he realized two things. The first was that he had just cursed in front of his highly impressionable eight-year-old son, who would now most assuredly walk around his home, his school, and the local playground for the next week yelling ‘Shit!’ at the top of his lungs. The second was that the flying cicada creature that had struck him – twice! – in the right thigh was nothing more than his own cell phone, which he’d left on vibrate in his front pants pocket. Feeling now like a complete idiot, he reached into his pocket and brought out the phone.

‘Shit! That’s no giant bug, Dad. That’s your phone,’ Joel pointed out enthusiastically.

‘Thank you, Joel,’ he said, looking at the phone’s digital display, which simply read: ‘CO.’ It was his assistant calling from the Coroner’s Office, which meant that the body was either on its way to the CO, or it had already arrived and would soon be ready for autopsy. In a case such as this, they would expect him to perform the autopsy tonight. Answering this call would be the beginning of a long, unpleasant evening.

‘Go ahead,’ Susan said with a smile as he glanced in her direction. ‘You’d better answer your cicada.’

Ben flipped the phone open, and took a few steps away from his wife and son. ‘Yes, hello,’ he said.

‘Dr S,’ the voice on the other end spoke excitedly. ‘It’s Nat.’

‘Hey. What’s up?’

‘You heard about that kid they found dead in the woods this afternoon, I guess. The one who was stabbed to death?’

‘Yeah. We heard.’

‘Well, the cops have finished with their crime scene investigation and they’re releasin’ the body to us. I’m about to head over there to pick him up right now.’

‘Okay. Just give me a call when you get back to the office and everything’s ready.’

‘Sure, Dr S. No problem. But, hey. There’s a lot of reporters settin’ up outside the CO with their camera crews ’n’ stuff, you know. Body’s not even here yet and they’re startin’ to gather round like they’re expecting an Elvis sighting or somethin’. I mean, this is a big case for us, don’t you think?’

‘Nat, listen to me.’ Ben kept his voice as calm and as clear as he could. He spoke slowly, hoping that by maintaining his own composure he could exert some positive influence on his overenthusiastic assistant. He doubted that it would do much good, but at least it was worth a try.

‘Yeah? What d’ya need me to do?’

Take two Valium and call me in the morning, Ben thought to himself. Instead, he said, ‘You’re right about this being an important case.’

‘Sure ’nough,’ Nat exclaimed. ‘Murder like this – in cold blood and all – ain’t somethin’ you see round here every day. That’s for sure.’

‘That’s right,’ Ben replied. ‘It’s not something we see around here every day. It’s big news in a small town, and those reporters are going to want some footage and a nice ten-second sound bite for the eight o’clock news.’

‘Ain’t that the truth. Things are about to get a lot more interesting round here. It’s gonna be a regular three-ring circus.’

‘You’re probably right,’ Ben agreed. ‘But right now we have a job to do. It’s an important job. A boy was murdered today. He’s lying on the ground surrounded by yellow police tape. And somewhere out there is a family whose son won’t be returning home tonight. Now, our job is to gather as much information as we can about how he died, and the evidence that we have is his body. If we do our job carefully and professionally, we might find something that will help the police track down his killer.’

‘That’s right,’ Nat agreed excitedly. ‘Wouldn’t that be somethin’? You think they’d want me to testify in court?’

‘Maybe. But I can tell you one thing for sure. If we let our emotions get the best of us – if we allow ourselves to be distracted and start thinking too much about the reporters and the police and the eight o’clock news – well, then we’ll screw it up. We’ll miss something, or allow a break in the chain of custody, or jump to some conclusion that we’ll regret later. But by then, it will be too late.’

‘Too damn late,’ Nat agreed seriously. His voice was quieter now, more subdued, and although Ben could still detect a hint of the earlier excitement just beneath the surface, the boy’s tone was held in check now by something of even greater significance: a sense of sobering responsibility. He could picture his young assistant standing in the lab’s small office with the phone held tightly in his right hand, the adrenaline-laced muscles of his body filled with purpose and ready to act. Nathan Banks was a good kid. At twenty-two, he was a bit young for the job of pathologist’s assistant. But Ben had known him for most of the boy’s life, and he was also friends with Nat’s father, who’d been flying for United Airlines for the past eighteen years and, as a commercial airline pilot, was away from home more often than not. Nat had taken an early fascination with the Coroner’s Office. He’d started volunteering there at the age of sixteen, helping Ben mostly by preparing and cleaning instruments, attending to certain janitorial duties and the like. But Nat also enjoyed watching and eventually assisting with the autopsies Ben performed. His mother, Karen, had given her hesitant permission, although she’d expressed some reservations to Ben about the interest her son had taken in the field. One afternoon she’d shown up at the office and had asked Ben with a worried look if he thought it was normal or healthy for a sixteen-year-old boy to want to spend his days working around dead people. Ben, who had entered medical school at the age of twenty-six, but who had volunteered both in his local hospital’s emergency department as well as at the Allegheny County Coroner’s Office since the age of eighteen, explained to Karen that her son’s interest in the work was probably nothing to worry about. It might even serve as a potential career someday, he’d suggested, and over the next two years Nat had slowly been allowed to assume a more hands-on role in the autopsies Ben performed. Eventually, he became skilled enough to be a real asset in the lab, and when Nat graduated from high school Ben had offered to turn his volunteer position into a paid one. Nat had enthusiastically accepted, and he had been working there ever since.

‘What you and I have to decide,’ Ben now said into the phone, ‘is whether we want to be part of the three-ring circus, or whether we want to act like professionals and focus on the job in front of us. You can do either one, Nat, but you can’t do both. What I need to know from you now is how you want to handle it.’

‘Well, let’s do our J-O-B,’ his assistant replied. ‘Don’t sweat it, Dr S – I’ve got your back.’

‘That’s what I needed to hear.’ Ben glanced back at Susan and Joel, who were standing on the sidewalk in the gathering darkness. ‘Listen, I’ve got something I need to do before heading over there. You think you can go pick up the body and give me a call on my cell once you get back to the CO?’

‘No problem.’

‘And if the reporters want a few words from you for the evening news, what are you going to tell them?’

‘I’ll tell them, “No muthafuckin’ comment!” Excuse my French. We’ve got a job to do.’

‘That’s right.’ Ben smiled, feeling a modicum of levity for the first time since arriving home that afternoon. ‘I’ll see you in a little while.’

‘Over and out,’ Nat saluted, and terminated the connection.

‘Over and out,’ Ben sighed to himself as he returned the phone to his pocket and turned back to his wife and son. A moment later, he heard the sound of an approaching diesel engine, and as it rounded the corner they were silhouetted in the headlight beams of the approaching bus.

Chapter 4

Fifty minutes later, Ben found himself sitting in the darkened interior of the Honda as he headed east toward the Coroner’s Office. A tentative drizzle had begun to fall from the sky as his family had walked home together from the bus stop, and by now it had progressed to a steady drumming that pattered the car’s rooftop insistently with its heavy, hollow fingers. A light fog clung to the ground, and Ben was forced to negotiate the dark, rain-slickened streets slowly and with exceptional caution. He’d habitually turned on the radio as he started the car, but most of the local stations were running news of the murder, and the more distant ones that he could sometimes pick up on clear days were reduced to static in the mounting storm. He flipped the knob to the off position and decided to simply concentrate on driving.

Thomas had stepped off the bus that evening to the warm embrace of his relieved and grateful parents, and to the boundless questions of his spellbound younger brother. As it turned out, Thomas didn’t have much more information on the identity of the victim or the details of the crime than his parents had already received from Phil Stanner. This stood to reason, since the police were remaining tight-lipped until after they’d had a chance to notify the victim’s family.

What was clear from the moment Thomas stepped off the bus to join them was that he regarded the day’s events with a certain quiet thoughtfulness that Ben had not anticipated. He spoke very little during the walk home, and let his family’s questions wash over him without much comment. Ben wondered whether his son might be in a mild state of shock, or simply trying to wrap his mind around the idea of a violent attack so close to home and school. Ben felt that children of Joel’s age tended to regard death as an obscure and distant entity, far removed from their own daily lives and therefore relatively inconsequential. This view seemed to change as children entered their teenage years and began to explore and sometimes even to court this previously intangible eventuality. Popular movies often romanticized the notion with blazing shoot-outs among beautiful people against an urban backdrop at sunset, or titanic ships that slowly sank in the freezing Atlantic while lovers shared their final fleeting moments together aboard a makeshift life raft only buoyant enough for one. This was not the type of death that Ben encountered as a physician. He supposed it could be described as many things, but mostly his experience with death was that it was impersonal, and seldom graceful.

During his intern year as a medical resident, Ben had been working his third shift in the emergency department when paramedics brought in a fifty-eight-year-old man with crushing substernal chest pain radiating to his left arm and neck. Ben had examined the patient quickly in the limited time available, and after reviewing the EKG he’d decided that the man was having a heart attack. Emergency treatment for heart attack patients with certain specific EKG changes called for the administration of thrombolytic agents, powerful clot-busting drugs designed to open up the clogged blood vessel and restore adequate blood flow to the heart. The supervising physician was not immediately available and the patient’s clinical condition seemed tenuous, so Ben had given the order for the nursing staff to administer the thrombolytic drug to his patient. The results had been almost immediate. Within five minutes, the patient was complaining of worsening pain, which was now also radiating to his back. Eight minutes later the patient’s blood pressure plummeted, his heart rate increased to 130 beats per minute and he vomited all over himself and the freshly pressed sleeve of Ben’s previously impeccably clean white coat. Several moments later the patient lost consciousness, and Ben could no longer palpate a pulse. He attempted to place a breathing tube into the patient’s trachea but couldn’t see past a mouthful of emesis. Instead, the tube slipped into the patient’s esophagus, and each squeeze of the resuscitation bag aerated the patient’s stomach instead of his lungs. Ben began CPR, and the first several compressions were accompanied by the sickening feel of cracking ribs beneath his interlaced hands. ‘Call Dr Gardner!’ he shouted to the charge nurse standing in the doorway, and he soon heard the overhead paging system bellowing: ‘Dr Gardner to the ER, stat! Dr Gardner to the ER, stat!’

For eight minutes Ben pumped up and down on his patient’s chest, attempting to circulate enough blood to generate some sort of blood pressure. Every so often, he paused long enough to look up at the patient’s heart rhythm on the monitor. ‘Shock him, two hundred joules!’ he ordered the nurse, who would charge the paddles, place them on the patient’s chest, yell ‘CLEAR!’ and press the two buttons that sent a surge of electricity slamming through the patient’s body like an electric sledgehammer. ‘No response, Doctor,’ the nurse reported each time, and Ben would order another round of electricity to be delivered like a mule kick into the patient’s chest before resuming chest compressions over splintering ribs. Somewhere during the nightmare of that resuscitation – Ben’s first resuscitation as a physician – the patient’s bladder sphincter relaxed and about a liter of urine came rushing out of the man’s body and onto the bedsheets. A small rivulet of urine began trickling steadily onto the floor. Ben continued his compressions on the patient’s mottled chest, which was now tattooed with burn marks from the defibrillator paddles, as the nurse had failed to place enough conductive gel on the paddles before delivering each shock. The room stank of burnt flesh and a repugnant potpourri of human sweat, urine and the vomited remains of a tuna fish sandwich that the patient had apparently eaten shortly prior to his arrival. The endotracheal tube, temporarily forgotten, slipped out of the patient’s esophagus and fell onto the floor with a resounding splat.

‘What in the hell is going on here, Dr Stevenson?!’ Dr Jason Gardner, Ben’s supervising physician, stood in the doorway, gaping in disbelief at the scene. He appeared to be moderately out of breath from having run across the hospital from the cafeteria on the other side of the building. Ben noticed a small bit of pasta clinging like a frightened animal to his yellow necktie.

‘Heart attack.’ Ben’s voice was hollow and uncertain, small and desperately apologetic, and his words fell from his mouth in a rush as he tried to explain. ‘He came in with chest pain radiating to his arm, neck, and back. Only history was hypertension. He had EKG changes – an ST-elevation MI, I thought. I gave him thrombolytics. I was going to call you, but I didn’t think there was enough time. He coded shortly after I gave the ’lytics. I tried CPR and defibrillation, but I couldn’t get him back. I don’t understand it. I had the nurse call for you as soon as he lost his pulses, but—’

‘What did his chest X-ray look like?’

‘His chest X-ray?’ Ben thought for a moment. Had he ordered one? ‘I … I don’t know. I think they got one when he first came in, but I didn’t get a chance to look at it.’

‘What do you mean you didn’t get a chance to look at it?’

‘I just … he started crashing, and there wasn’t enough time …’

‘For God’s sake, Stevenson! Stop doing compressions and go get me the goddamn chest X-ray!’

Ben looked down at his hands, surprised to see that they were still pressing up and down on the patient’s chest. He forced them to stop. ‘Maybe if we tried another shock …’ he suggested hopefully.

‘The patient’s dead,’ Gardner growled. ‘You can shock him all you want, and he’s still going to be just as dead. Now, go get that X-ray. Let’s see what you missed.’

Ben left the room and walked across the hallway to the viewing box. A wooden repository hung on the wall containing several manila sleeves of radiographic images. He shuffled through them, found the appropriate one and returned with it to the resuscitation room. Dr Gardner stood next to the cooling body, leafing through the patient’s chart. Ben noticed that the dead man’s eyes remained open, staring lifelessly at the door through which he’d recently entered. Throughout the course of his career, Ben would never forget the look of those eyes, which were not accusatory or vengeful, but simply, unabashedly dead. For some reason, that was the worst of it – the detached finality of that look. It was the first thing he learned that day; when things go bad in this line of work and someone dies, there is always plenty of blame to go around, but there is only one soul who truly no longer cares.

‘Let’s see that film,’ Gardner grunted, and Ben handed him the envelope. He watched the man remove the X-ray from its sleeve and slap it onto the resuscitation room’s viewing box. The seasoned physician studied it for a minute, then queried, ‘Well, what do you make of it, Dr Stevenson?’

Ben cleared his throat hesitantly. ‘The lung fields are somewhat hyperinflated. Cardiac silhouette appears slightly enlarged, although that can be an artifact of a single AP view. Costophrenic margins are well visualized. No evidence of an infiltrate or pneumothorax.’

‘Uh-huh. And how would you describe the mediastinum?’

‘Widened. The aortic knob is poorly visualized.’

‘Exactly. What comes to mind, Dr Stevenson, in a fifty-eight-year-old gentleman with a history of hypertension, who presents with chest pain radiating to his arm and back and has a widened mediastinum on chest X-ray?’

‘Aortic dissection?’ Ben ventured. ‘But what about the ST elevation on the patient’s EKG?’

Gardner snatched up the EKG, glanced at it perfunctorily, then handed it to Ben. ‘Inferior ST elevation consistent with a Stanford type A aortic tear dissecting into the right coronary artery. Pushing thrombolytics on this man was a death sentence. He bled into his chest and pericardial sac within minutes. He would’ve stood a better chance if you’d just walked up to him and shot him in the head with a .38.’

Those last words – Dr Gardner’s final commentary on the case – hung in the air, defying objection. Ben stood in the room between his boss and the dead man, unable to conjure any sort of meaningful response. His face burned with anguish and humiliation. In the corner of the room, a nurse pretended to scribble notes on the patient’s resuscitation sheet. She glanced up briefly in Ben’s direction, her face cautiously guarded.

‘Notify the medical examiner, and submit this case to the M&M conference on Friday,’ Dr Gardner instructed him. ‘Get back to work. You’ve got three patients in the rack still waiting to be seen. Oh, and Stevenson?’

‘Yes?’ Ben looked up, needing to hear some token of consolation from his mentor, this man he respected.

‘Try your best not to kill the rest of them,’ Gardner advised him blandly, and left the room without looking back.

One of the hardest things about being a physician, Ben now thought as he recollected this horrendous experience in the ER as a young intern, was forcing yourself to continue along in the wake of such catastrophic events as if nothing had happened. The three patients still waiting to be seen had turned out to be a child with a common cold, a drunk teenager who was brought to the emergency department by her friends and a forty-two-year-old man with a wrist fracture. Routine, mundane cases, in other words. Ben had attempted to clear his head as best he could, and he interviewed and examined them all carefully and professionally. But while looking into the child’s ears with an otoscope, he thought to himself, I just killed a man. While ordering an anti-emetic for the teenager now puking through the slots between the side rails of her gurney, he thought, There’s a man in Resuscitation Room 2 covered by a white sheet because I was in too much of a hurry to look at a simple chest X-ray. In the middle of examining the man’s broken wrist, he recalled holding the wrist of the dead man in his hands as he searched for a pulse that was no longer there. During these moments, his patients were aware of none of this. Two more people arrived in the department during the time he had taken to examine and treat the previous three patients. After that, an ambulance had shown up with a moderately severe asthmatic, and four more people checked in to triage.